Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

To help you frame and write your literature review, think about these five c’s (Callahan, 2014):

- Cite the material you have referred to and used to help you define the research problem that you will study.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methods, and findings expressed in the literature.For example, describe where the various researchers agree and where they disagree. Describe the similarities and dissimilarities in approaches to studying related research problems.

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methods, approaches, and controversies apparent and/or described in the literature. For example, describe what major areas are contested, controversial and/or still in debate.

- Critique the literature. Describe which arguments you find more persuasive and explain why. Explain which approaches, findings, and methods seem most reliable, valid, appropriate, and/or most popular and why. Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what previous researchers have stated (e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, clarifies, etc.).

- Connect the various research studies you reviewed. Describe how your work utilizes, draws upon, departs from, synthesizes, adds to or extends previous research studies.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Licensing Information

- Contributing Authors

- 1. Let's Get Writing

- 1.1. The 5 C Guidelines

- 1.2. How to Write Articles Quickly and Expertly

- 2. Critical Thinking

- 2.1. Critical Thinking in the Classroom

- 2.2. Necessary and Sufficient Conditions

- 2.3. Good Logic

- 3. APA for Novices

- 3.1. Hoops and Barriers

- 3.2. Crafts and Puzzles

- 3.3. The Papers Trail

- 3.4. The Fine Art of Sentencing

- 3.5. Hurdles

- 3.6. Small Stressors

- 4. Literature Reviews

- 4.1. Introduction to Literature Reviews

- 4.2. What is a Literature Review?

- 4.3. How to Get Started

- 4.4. Where to Find the Literature

- 4.5. Evaluating Sources

- 4.6. Documenting Sources

- 4.7. Synthesizing Sources

- 4.8. Writing the Literature Review

- 4.9. Concluding Thoughts on Literature Reviews

- Technical Tutorials

- Constructing an Annotated Bibliography with Zotero

- Extracting Resource Metadata from a Citation List with AnyStyle.io

- Exporting Zotero to a Spreadsheet

- APA 7 Job Aid

- Index of Topics

- Translations

The 5 C Guidelines

Choose a sign-in option.

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Producing good academic writing is a difficult skill to master, and writing for an academic audience is different than writing for other audiences.

As an academic writer, you must approach topics differently than you might as a journalist or creative author, and you must emphasize certain skills, such as writing clearly, and ignore other skills that you might have been taught in other contexts, such as using expressive imagery.

To introduce you to this world of academic writing, in this chapter I suggest that you should focus on five hierarchical characteristics of good writing, or the “5 Cs” of good academic writing, which include Clarity, Cogency, Conventionality, Completeness, and Concision. I will now explain each of these in more depth and then discuss tensions between them in writing for different academic audiences.

"Ambiguity is very interesting in writing; it's not very interesting in science." — Janna Levin

Many of us were taught in writing courses that ambiguity and obfuscation of meaning are laudable, because they make our writing seem more complex, deep, and witty. And many of our favorite novelists likely use ambiguity and other tricks to make their writing seem mysterious and complex.

In academic writing, though, these practices simply suggest that you don’t know what you’re talking about. For academics, writing is a way of uncovering truths and realities of the social and physical world, so we should say what we mean. We should make it clear, and say it so that it is impossible for our audience to misunderstand. If your imagined reader ever has to squint her eyes and muse “I wonder what the author really meant by this,” then you have failed. If your imagined reader ever smiles to herself and chuckles at your brilliant wordplay, then you have failed.

This is not to say that academic writing must be joyless and stodgy. It can be witty. It can be deep. But academic depth and wit come from the ideas portrayed through the words, not the words themselves. Too often, writers use ambiguity to hide sloppy thinking and beautiful language to hide destitute ideas. If you say something that could potentially be misunderstood, explain it. If a simpler word will do in place of a more complex one, then use the simple word. Don't be afraid of laying out complex ideas across multiple sentences or paragraphs, but use the space available to you to open up your mind to your reader — what exactly you are thinking, how you are thinking about it, and why.

If you use jargon, technical terms, or initialisms, then you should define or operationalize them. Defining a term means that you are relying upon someone else’s explanation of what the term means and are sticking with it (e.g., “Marwick defines ‘social media’ as…”). Operationalizing a term means that you are using a term that might mean multiple things but you are deciding to only use it in a very finite and specific manner (e.g., “In this paper, I use the word ‘engagement’ to mean…”).

In the case of initialisms, no reader should be expected to know what a PBL, SNS, LMS, CMS, or PBIS is by virtue of the letters themselves, and often even technical initialisms might have multiple meanings (e.g., PBL in education might refer to “project-based learning” or “problem-based learning”). So, when you use initialisms in your writing, define them at the outset (e.g., “positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS)”).

If you find yourself repeating the same words over and over again, that’s okay; don’t use variety in your language just for the sake of variety, because in highly technical academic fields every word carries with it technical baggage that you may not intend. If I’m talking about a “curriculum,” then I shouldn’t swap this out with “program,” “module,” “subject,” or “materials” just because I’m tired of saying “curriculum;” each of these words means something very different, and using these terms interchangeably just shows my reader that I don’t understand the differences between them.

In short, other types of writing often rely upon ambiguity and obfuscation to prevent their underlying thought processes from being examined, but examination of these processes is the whole purpose of academic writing. We are not poets, politicians, or preachers, whose primary goals are to be convincing or mystical; rather, we are fellow learners that can only learn together insofar as we can clearly reason together through a dialogic process of clear writing.

"Logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end." — Leonard Nimoy

Your writing should follow a logical pattern or argument. Arguments generally follow a pattern of identifying one or more assumptions, providing evidence, and drawing a conclusion, such as:

- Assumption - Test creators should design tests to be equitable to all learners who may represent various demographic differences (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender);

- Evidence - Specific research studies show that some prominent tests exhibit inequitable outcomes for students based on race and ethnicity;

- Conclusion - Therefore, test creators should seek to understand why such tests are biased toward some students and should seek to remedy this issue.

Once a conclusion is drawn, it can then be used as an assumption for a subsequent argument. This means that the overarching argument for a paper actually consists of many micro-arguments made throughout the paper that build upon one another like bricks in a wall. Essentially, each paragraph in an academic paper should be treated as its own separate argument, and these arguments then build off of each other to construct the overarching argument.

To help reveal your logical structure, each paragraph should generally represent its own argument. It should start with a topic sentence, provide evidence, and then draw a conclusion that you then build upon in the next paragraph. This is what people often refer to as logical flow: moving from one idea to another without any unsubstantiated gaps.

Since you must substantiate each claim that you make in an academic paper, you should also be careful not to overstate claims (e.g., using superlative language) and not to make claims that you cannot provide evidence for. Oftentimes, this is done by toning down language (e.g., "project-based learning can be an effective pedagogical strategy" [toned down] vs. "project-based learning is the best pedagogical strategy" [superlative]) and using helping verbs, such as may, can, and might (e.g., "social media use may contribute to student depression" vs. "social media make kids depressed"). By toning down your language, you introduce possibilities for doubt (which academics should always be open to) and also prevent your argument from being invalidated by a single counter-instance (e.g., "my kid uses social media and is not depressed, therefore your argument is invalid").

Conventionality

"Writing [without structure] is like playing tennis with the net down." — Robert Frost

In order to understand each other and to know what to expect when we are reading a new manuscript, we need some conventions to provide uniformity. If every article you read had a unique structure, formatting, spacing, capitalization, font size, style, tone, and so forth, you would have increased difficulty comparing it to other work that had gone before.

However, if every time you approach a new piece of writing you know what to expect and where to find it, you will be able to more efficiently recognize where to go and what to look for in the paper. Rather than hunting for the research question, you will know that it will be found right before the methods section and that results will be provided right after that section. Similarly, when you see a bolded and centered line of text, you will know that this means that a new top-level (H1) section is beginning and are not left to wonder why the author made such a bold stylistic choice.

For these reasons, groups of academics have sets of guidelines that they agree to follow, and in our field we follow the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Handbook (version 6). That handbook covers everything from structure and formatting to style and tone, and theses, dissertations, and class projects require students to follow these same guidelines to help ensure that student work is written in a way that will allow it to be published to a wider audience.

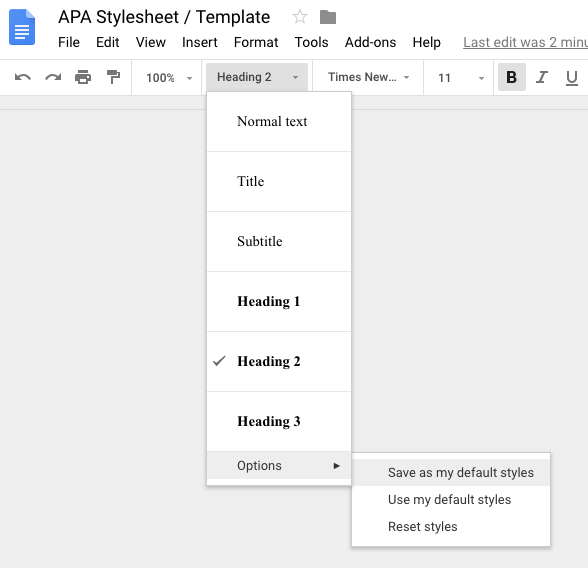

APA Template

To assist you in following APA guidelines, you can access this Google Document that has proper APA heading formats built into it. Then, click on the Styles dropdown > Options and save the APA styles as your default styles, thereby making any new documents that you create in Google Drive follow the APA conventions.

Completeness

"Our duty is to believe that for which we have sufficient evidence, and to suspend our judgment when we have not." — John Lubbock

Since the goal of academic work is to inform as broad an audience as possible and to stand up under the scrutiny of diverse sets of eyes, you must flesh out your writing to address all of the major questions and doubts that your readers might have. Thus, you must not only make an argument that might be convincing to a few people, but you must include sufficient detail and explanation to allow your writing to hold under the scrutiny of the most critical reader. That is, you must write for your greatest critic, not your greatest fan.

This is why academic publishing relies upon peer review. The assumption of peer review is that the best way to ensure quality of writing is to put an author’s work in the hands of dispassionate, unbiased, and diverse experts who typically do not know the identity of the author. This allows reviewers to be honest in their feedback and prevents them from relying upon their personal relationships with or knowledge of the author to fill any gaps (e.g., “I’ve heard of Dr. Avila, and she’s done great work before, so I’m assuming that she did good work here, too”). Rather, every piece of academic writing must stand or fall on its own merits and not on the author’s prior quality of work or reputation.

To do this, you must be explicit and detailed, assume that your reader does not know or trust you as the author, and treat every piece of academic writing as a completely self-contained, self-sustaining, self-validating artifact.

"Brevity is the soul of wit."— William Shakespeare

Most journals in education and other social sciences have strict article word limits of 4,000 to 7,000 words, or roughly 20 to 30 double-spaced pages. This historically has been done to accommodate publishing limitations, because printing pages in a journal is expensive, but even in a digital world, with practically zero publishing costs for adding additional words, imposing limits helps to reduce information overload on readers and to drive more readers to your work.

After all, a moderately-interested reader is much more likely to read a ten-page synopsis of your dissertation than the 200-page document itself, and only the most devoted of readers will stick with it after 20 pages or so. This means that you as the author must not only meet all of the requirements established by the previous guidelines, but you must do it on a strict word budget that avoids unnecessary detail or repetition.

Tensions and Relative Importance

As you’ve probably guessed by this point, the demands of each of these guidelines sometimes conflict with one another. For instance, being complete might mean that you are not very concise, and being clear might reveal the irrationality or poor cogency of your argument. At such times, you must prioritize the guidelines to determine which to emphasize and which to ignore.

Depending on the type of academic writing you are doing, the way that you prioritize guidelines may vary. For instance, a journal article will normally value concision over completeness, due to publishing word limits and trying to make the article as accessible as possible to a wide audience, while a systematic literature review for a thesis or dissertation will do the opposite, requiring students to reveal all of their understanding of their topic and how it is situated within the broader field so that their committees can be assured that they actually know what they are talking about.

Similarly, a quantitative empirical paper will rely heavily upon the conventions established by the paradigm (e.g., p-values, effect sizes), while a qualitative empirical paper will need to provide completeness in its descriptions to allow for trustworthiness and at times ignore conventions. Theoretical papers will also often necessarily defy some conventions in favor of laying out a clear and cogent argument, because the proposed ideas will be new and will not neatly fit within existing reporting approaches but will nonetheless need to be argued in a reasonable and compelling manner.

All this is to say that though these guidelines are all important, their relative importance to one another varies by the context of the writing as determined by purpose, audience, and methods.

Relative Importance of the 5 Cs in Different Settings

| Relative Importance | Journal Article | Thesis or Dissertation |

|---|---|---|

| Most Important | Concision | Completeness |

| Conventionality | Clarity | |

| Clarity | Cogency | |

| Cogency | Conventionality | |

| Least Important | Completeness | Concision |

By focusing on these 5 Cs and each of their relative importance for your writing context, you can begin to approach your own work in a manner that is systematic and self-reflective. If writing a thesis, for instance, I should start by asking myself "Am I including all pertinent information and details? Is my meaning clear? Is my logic sound? Am I following APA guidelines? And am I careful not to repeat myself or belabor my point?" If writing a theoretical argument for a journal, on the other hand, I should ask myself "Am I within the word limit for the journal? Am I following the journal's stylistic guidelines? Is my argument strong? Is my meaning clear? And do I cover everything that I need to in order to preempt any concerns?"

When asking these questions, something always has to give, such as cutting that explanatory paragraph to get an article under the journal’s required word limit or adding an additional paragraph to make it clear to your thesis readers that you understand the implications of what you’re saying. Through it all, however, each of these guidelines is generally important to follow, and you can only justify ignoring one temporarily in those cases where tensions exist and your intended audience requires you to prioritize another guideline in its place.

Brigham Young University

This content is provided to you freely by EdTech Books.

Access it online or download it at https://edtechbooks.org/rapidwriting/5Cs .

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a literature review in 6 steps

What is a literature review?

How to write a literature review, 1. determine the purpose of your literature review, 2. do an extensive search, 3. evaluate and select literature, 4. analyze the literature, 5. plan the structure of your literature review, 6. write your literature review, other resources to help you write a successful literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a literature review, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

A good literature review does not just summarize sources. It analyzes the state of the field on a given topic and creates a scholarly foundation for you to make your own intervention. It demonstrates to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

In a thesis, a literature review is part of the introduction, but it can also be a separate section. In research papers, a literature review may have its own section or it may be integrated into the introduction, depending on the field.

➡️ Our guide on what is a literature review covers additional basics about literature reviews.

- Identify the main purpose of the literature review.

- Do extensive research.

- Evaluate and select relevant sources.

- Analyze the sources.

- Plan a structure.

- Write the review.

In this section, we review each step of the process of creating a literature review.

In the first step, make sure you know specifically what the assignment is and what form your literature review should take. Read your assignment carefully and seek clarification from your professor or instructor if needed. You should be able to answer the following questions:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What types of sources should I review?

- Should I evaluate the sources?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or critique sources?

- Do I need to provide any definitions or background information?

In addition to that, be aware that the narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good overview of the topic.

Now you need to find out what has been written on the topic and search for literature related to your research topic. Make sure to select appropriate source material, which means using academic or scholarly sources , including books, reports, journal articles , government documents and web resources.

➡️ If you’re unsure about how to tell if a source is scholarly, take a look at our guide on how to identify a scholarly source .

Come up with a list of relevant keywords and then start your search with your institution's library catalog, and extend it to other useful databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Science.gov

➡️ Our guide on how to collect data for your thesis might be helpful at this stage of your research as well as the top list of academic search engines .

Once you find a useful article, check out the reference list. It should provide you with even more relevant sources. Also, keep a note of the:

- authors' names

- page numbers

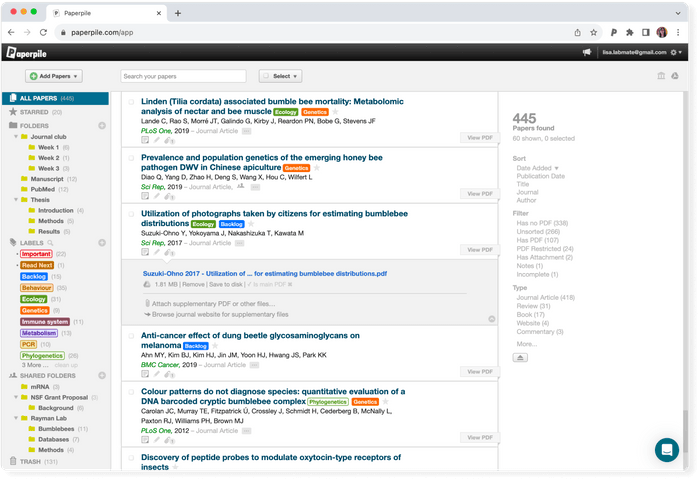

Keeping track of the bibliographic information for each source will save you time when you’re ready to create citations. You could also use a reference manager like Paperpile to automatically save, manage, and cite your references.

Read the literature. You will most likely not be able to read absolutely everything that is out there on the topic. Therefore, read the abstract first to determine whether the rest of the source is worth your time. If the source is relevant for your topic:

- Read it critically.

- Look for the main arguments.

- Take notes as you read.

- Organize your notes using a table, mind map, or other technique.

Now you are ready to analyze the literature you have gathered. While your are working on your analysis, you should ask the following questions:

- What are the key terms, concepts and problems addressed by the author?

- How is this source relevant for my specific topic?

- How is the article structured? What are the major trends and findings?

- What are the conclusions of the study?

- How are the results presented? Is the source credible?

- When comparing different sources, how do they relate to each other? What are the similarities, what are the differences?

- Does the study help me understand the topic better?

- Are there any gaps in the research that need to be filled? How can I further my research as a result of the review?

Tip: Decide on the structure of your literature review before you start writing.

There are various ways to organize your literature review:

- Chronological method : Writing in the chronological method means you are presenting the materials according to when they were published. Follow this approach only if a clear path of research can be identified.

- Thematic review : A thematic review of literature is organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time.

- Publication-based : You can order your sources by publication, if the way you present the order of your sources demonstrates a more important trend. This is the case when a progression revealed from study to study and the practices of researchers have changed and adapted due to the new revelations.

- Methodological approach : A methodological approach focuses on the methods used by the researcher. If you have used sources from different disciplines that use a variety of research methods, you might want to compare the results in light of the different methods and discuss how the topic has been approached from different sides.

Regardless of the structure you chose, a review should always include the following three sections:

- An introduction, which should give the reader an outline of why you are writing the review and explain the relevance of the topic.

- A body, which divides your literature review into different sections. Write in well-structured paragraphs, use transitions and topic sentences and critically analyze each source for how it contributes to the themes you are researching.

- A conclusion , which summarizes the key findings, the main agreements and disagreements in the literature, your overall perspective, and any gaps or areas for further research.

➡️ If your literature review is part of a longer paper, visit our guide on what is a research paper for additional tips.

➡️ UNC writing center: Literature reviews

➡️ How to write a literature review in 3 steps

➡️ How to write a literature review in 30 minutes or less

The goal of a literature review is to asses the state of the field on a given topic in preparation for making an intervention.

A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where it can be found, and address this section as “Literature Review.”

There is no set amount of words for a literature review; the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

Most research papers include a literature review. By assessing the available sources in your field of research, you will be able to make a more confident argument about the topic.

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

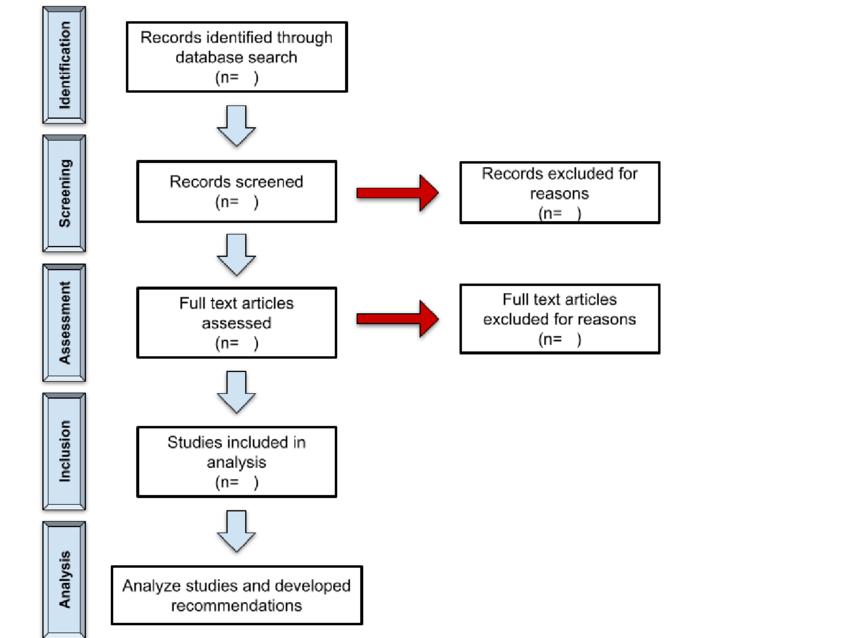

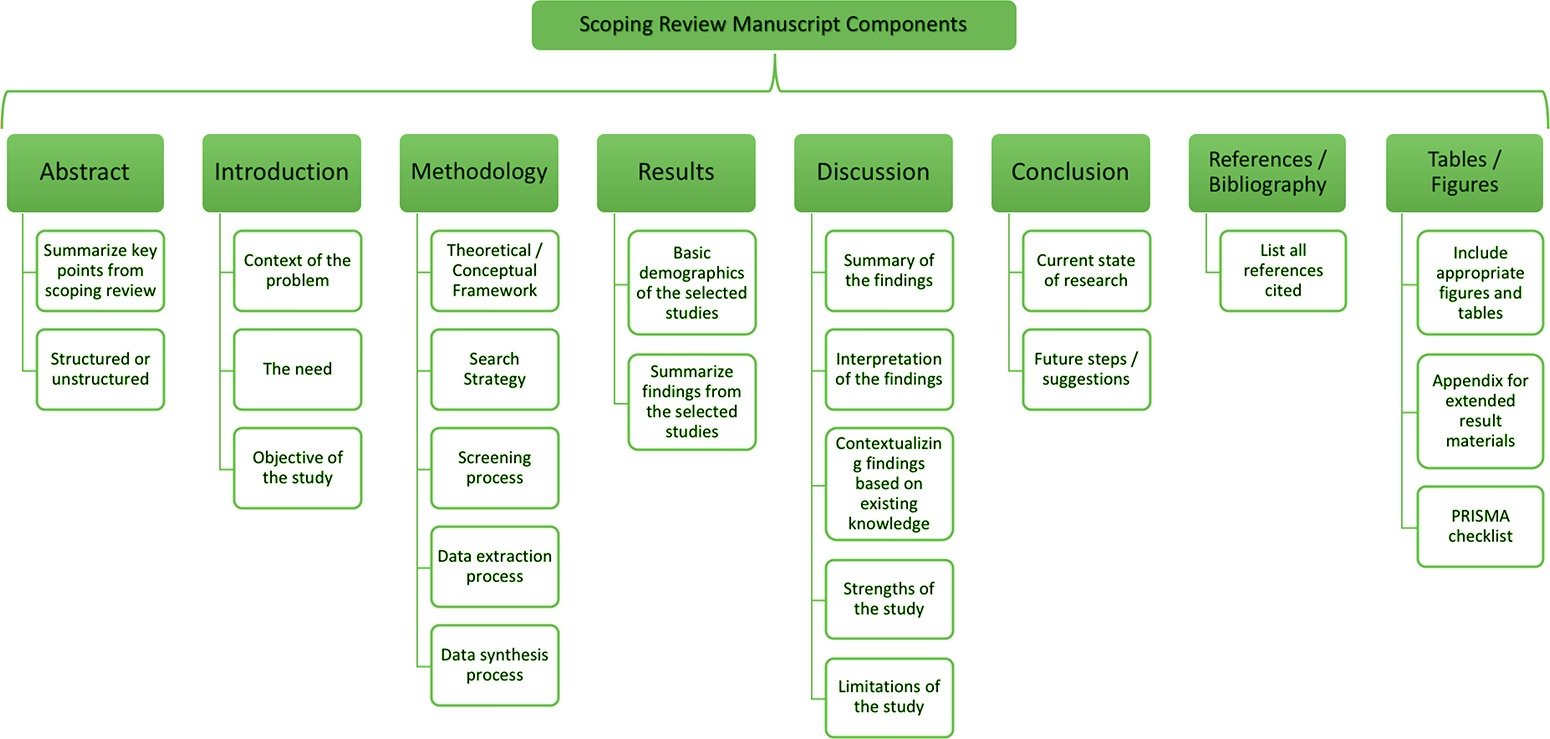

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?