Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The long-term effects of perceived instructional leadership on teachers’ psychological well-being during COVID-19

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations School of Information Engineering, Shandong Youth University of Political Science, Jinan, Shandong, China, Faculty of Education, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, Shandong, China

Roles Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Education, Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] (I-HC); [email protected] (JHG)

Affiliation Chinese Academy of Education Big Data, Qufu Normal University, Qufu, Shandong, China

Roles Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of English, National Changhua University of Education, Changhua, Taiwan

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Yangan Primary School of Qionglai City, Qionglai, Sichuan, China

Affiliation Gaogeng Nine-year School, Qionglai, Sichuan, China

Roles Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Shandong Provincial Institute of Education Sciences, Jinan, Shandong, China

- Xiu-Mei Chen,

- Xiao Ling Liao,

- I-Hua Chen,

- Jeffrey H. Gamble,

- Xing-Yong Jiang,

- Xu-Dong Li,

- Published: August 19, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494

- Reader Comments

The COVID-19 outbreak led to widespread school closures and the shift to remote teaching, potentially resulting in lasting negative impacts on teachers’ psychological well-being due to increased workloads and a perceived lack of administrative support. Despite the significance of these challenges, few studies have delved into the long-term effects of perceived instructional leadership on teachers’ psychological health. To bridge this research gap, we utilized longitudinal data from 927 primary and secondary school teachers surveyed in two phases: Time 1 in mid-November 2021 and Time 2 in early January 2022. Using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), our findings revealed that perceptions of instructional leadership, especially the "perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy" at Time 1 were positively correlated with burnout levels at Time 2. Additionally, burnout at Time 2 was positively associated with psychological distress and acted as a mediator between the "perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy" and psychological distress. In light of these findings, we recommend that schools prioritize teachers’ teaching autonomy and take proactive measures to mitigate burnout and psychological distress, aiming for the sustainable well-being of both teachers and students in the post-pandemic era.

Citation: Chen X-M, Liao XL, Chen I-H, Gamble JH, Jiang X-Y, Li X-D, et al. (2024) The long-term effects of perceived instructional leadership on teachers’ psychological well-being during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 19(8): e0305494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494

Editor: Ali B. Mahmoud, St John’s University, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Received: April 29, 2023; Accepted: May 30, 2024; Published: August 19, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Chen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This study was financially supported by the 2021 National Social Science Foundation of China (NSSFC) “Research on Mixed Ownership Model of Vocational Education” in the form of an award (BJA210105) received by I-HC. No additional external funding was received for this study. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1 Introduction

In response to the outbreak of COVID-19, countries worldwide implemented protective measures, such as physical distancing, to prevent the spread of the virus, resulting in the closure of schools globally [ 1 ]. The closure of schools has not only affected students’ psychological well-being [ 2 – 5 ], but has also caused a significant level of stress among teachers [ 6 , 7 ]. Studies indicate that teachers experienced pressure during the closure period due to mandatory teaching of online courses [ 8 ], increased teaching workloads [ 9 ], lack of support from administrators [ 10 , 11 ], and poor communication with students and parents [ 9 ]. Additionally, teachers suffered from symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances [ 12 ]. As such, the literature has provided mounting evidence to suggest that COVID-19 has caused considerable psychological distress among teachers [ 13 – 15 ].

Recent studies have underscored the potential long-term consequences of pandemic-induced stress, which can erode protective factors such as teachers’ resilience. This erosion can lead to burnout [ 16 ] and adversely affect their psychological well-being [ 17 – 19 ]. The challenges are compounded by the fact that school closures and the shift to online teaching have heightened the risk of burnout among teachers [ 20 ]. This exacerbates their already significant levels of psychological distress [ 21 , 22 ], leading researchers to delve deeper into the factors contributing to job burnout and psychological distress among educators.

Building on this, individual-level factors during COVID-19 have been extensively studied. These include role conflict [ 23 ], professional experience (such as the number of years spent teaching) [ 24 ], teacher professional identity (which encompasses individual beliefs, values, and commitments related to the teaching profession) [ 25 ], and perceptions about one’s ability to control situations [ 26 ]. This also covers competence in online teaching tasks [ 27 ] and anxiety related to communicating with parents [ 28 ]. On the organizational front, Maslach et al. [ 29 ] posited that burnout stems from extended exposure to work-related stressors. Thompson et al. [ 30 ] introduced the Six Areas of Worklife model, pinpointing workload, control, reward, and values as organization-level factors linked to burnout, especially during the COVID-19 era. Other organization-level factors contributing to teacher burnout include work climate, work pressure, perceptions of collective exhaustion among peers, disruptions to conventional classroom teaching [ 31 ], diminished administrative support [ 28 , 32 ], and supervisory management styles [ 33 , 34 ]. Research has also highlighted the correlation between principals’ leadership styles and teacher burnout [ 35 – 37 ]. Moreover, numerous studies have identified teacher burnout as a significant predictor of psychological distress in educators [ 21 , 38 , 39 ].

While the significance of both individual-level and organization-level factors related to burnout has been assessed in the context of COVID-19, organization-level factors have not been sufficiently evaluated. Indeed, the education department should place greater emphasis on factors at the organizational level when implementing decisive measures to address them. Instructional leadership, a pivotal aspect of school leadership [ 40 , 41 ], has yet to be thoroughly explored in terms of its impact on teachers’ well-being during the pandemic. To date, there seems to be a gap in the literature regarding how teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership influence their experiences of burnout and psychological distress, especially during school closures. This gap is particularly evident in studies focusing on the longitudinal effects of perceived instructional leadership on the mental health of Chinese teachers. Given this context, this study seeks to address the following research question: How do teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership affect their subsequent experiences of burnout and psychological distress ?

To address the above gap, our study undertook two waves of data collection: the first wave was gathered during the period of online teaching when campuses were closed, aiming to gauge teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership. The second wave was collected after the resumption of face-to-face classes to assess teacher burnout and psychological distress. The objective of this paper is to explore the relationship between perceived instructional leadership and subsequent burnout and psychological distress using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM). In this context, teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership are considered at the school level, while burnout and psychological distress are evaluated at the individual (teacher) level. The subsequent section will present the model and research hypotheses.

2 Model and hypothesis

In the present research, we employed longitudinal data to systematically examine the influence of teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership on subsequent manifestations of job burnout and psychological distress, as delineated in Fig 1 . To operationalize the construct of perceived instructional leadership, we grounded our categorization within the tenets of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), segmenting it into three distinct categories. To elucidate the interrelationships among these variables, we anchored our investigation in the Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) model, as proposed by Koeske and Koeske [ 42 ], subsequently formulating pertinent research hypotheses.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The dotted line represents the indirect effect of perceived instructional leadership at Time 1 on psychological distress at Time 2.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.g001

2.1 The SSO model

The Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) model explains how work-related stressors negatively impact employee behavior through psychological strain, and conceptualizes strain as a mediating factor [ 42 ]. Stressors, in the SSO model, are environmental stimuli that employees perceive as bothersome and disruptive, such as excessive workload, a lack of support, and conflicting roles [ 42 – 44 ]. Strain, on the other hand, is a negative reaction to environmental stimuli that disrupts employees’ concentration, effecting their physiology and mood [ 42 , 45 ], with burnout as a common manifestation [ 42 , 43 ]. Outcome refers to the lasting behavioral or psychological effects of chronic stress and strain, such as physical or psychological symptoms (e.g., psychological distress in the workplace).

Based on the aforementioned concerns, three perceptions of school instructional leadership were evaluated by this study as disruptive environmental stimuli (i.e., stressors): perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy, perceived school neglect of teaching competence, and perceived school emphasis on competitive relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies shown that burnout is often conceptualized as a strain in response to environmental stimuli in SSO model [ 42 , 43 ]. The construct of job-related burnout was proposed by Freudenberger [ 46 ] to describe the extreme physical and emotional exhaustion experienced by individuals due to excessive workloads. Maslach et al. [ 29 ] later defined burnout as "a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job," characterized by exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Emotional exhaustion, in particular, is considered the central component of burnout [ 42 , 47 ]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, emotional exhaustion maybe a negative reaction to teachers’ perceived instructional leadership [ 48 , 49 ].

As per the SSO model, stressors produced by three perceptions of instructional leadership may result in psychological distress (outcome) in teachers, with burnout (strain) mediating the relationship between the two. In the following subsections, the hypothesized relationships between these variables are presented sequentially.

2.2 Operationalizing perceived instructional leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: A tripartite categorization based on SDT

Instructional leadership is widely recognized as the cornerstone of school leadership [ 40 , 41 ]. Narrow conceptions of instructional leadership focus solely on teacher behaviors that augment student learning, whereas broader interpretations encompass issues related to both organizational and teacher culture [ 50 ]. According to Alig-Mielcarek and Hoy [ 51 ], instructional leadership comprises three primary components: (1) defining and communicating goals, (2) monitoring and providing feedback on the teaching and learning process, and (3) promoting and emphasizing the significance of professional development. Consequently, instructional leadership has emerged as an indispensable element of school reform and enhancement [ 51 ]. It influences a myriad of factors pivotal to the resilience of educational institutions, ranging from "organizational silence" (where crucial events or concerns remain unvoiced) to "organizational attractiveness" (reflecting positive sentiments towards an institution) [ 52 ].

The construct of instructional leadership in this study differs from the predominate perspective, which emphasizes leaders’ roles in stimulating teachers’ effectiveness in teaching and learning and improving students’ outcomes [ 53 ]. During the COVID-19 period, a more directive leadership style is indispensable to efficiently guide teachers in adapting to the unfamiliar task of online teaching [ 54 , 55 ], and it can be considered a special form of "instructional leadership" under pandemic conditions. It is uniquely adapted for the pandemic context and can reflect the teachers’ perceived instructional leadership in the context of epidemic. Specifically, drawing from the SDT, this study categorizes teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership during school closures into three distinct categories: perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy, perceived school neglect of teaching competence, and perceived school emphasis on competitive relationships. As posited by SDT, every individual harbors three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [ 56 , 57 ]. The fulfillment of these needs is essential for an individual’s holistic development, and any deficiency can adversely impact their psychological well-being [ 57 ]. In this context, perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy denotes teachers’ sentiments that schools overlooked their online teaching autonomy, compelling them to adhere to specific teaching standards and methodologies, thereby affecting perceived autonomy. Perceived school neglect of teaching competence signifies teachers’ perceptions that schools disregarded their online teaching competence during the closure, marked by a lack of provision for necessary online teaching training and an apparent indifference to the challenges of online/distance teaching, thereby affecting perceived competence. The perception of the school emphasizing competitive relationships suggests environments where competition among teachers was unduly promoted, engendering a detrimental atmosphere concerning relatedness. These constructs, which pertain to the neglect of teacher autonomy and competence and the prioritization of competition over collaboration, can be considered stressors in pandemic context. They have largely remained unexplored empirically. In contrast, supportive instructional leadership styles, which have been linked with a sustainable sense of agency, teacher expertise, and positive peer relationships, are documented in sustainable education literature [ 58 , 59 ].

2.3 Perceived instructional leadership and burnout

In this study, we examine the impact of perceived instructional leadership on teachers’ job burnout during the school closure period. In the previous research, it was found that principals’ leadership was related with teacher burnout [ 35 – 37 ]. Eyal and Roth [ 35 ] found that while transactional leadership (which seeks efficiency through monitoring and ensuring compliance through rewards and punishments) was positively correlated with burnout, transformational leadership (characterized by empowering and fostering individuals’ sense of mission through encouragement of innovation based on individual needs) was negatively correlated with burnout. Collie’s findings [ 36 ] highlighted that autonomy-supportive leadership (which refers to practices that promote individuals’ self-initiation and empowerment) was associated with lower emotion exhaustion and autonomy-thwarting leadership (which refers to practices that exert external control and reduce individuals’ self-determination) was positively associated with emotional exhaustion. Based on instructional leadership has been accepted as the core of school leadership [ 40 , 41 ], our first hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) is that teachers’ perceived instructional leadership would be positively associated with teachers’ job burnout. Specifically, we propose three sub-hypotheses based on the dimensions of instructional leadership that have been suggested as significant stressors, based on the SSO.

H 1a : Perceived instructional leadership that neglects teaching autonomy will have a positive relationship with job burnout. Previous research has shown a strong relationship between burnout and autonomy [ 29 , 36 , 60 , 61 ]. Teachers who are unable to choose their own teaching methods during remote teaching may experience negative attitudes towards teaching activities, dissatisfaction with their work, and depression [ 62 ].

H 1b : Perceived instructional leadership that neglects teaching competence will have a positive relationship with burnout. During the school closure period, teachers were not provided with required training for online teaching, and some may feel that the school was not paying attention to their teaching abilities. This lack of support may result in increased teaching pressures and a sense of incompetence, leading to burnout [ 34 , 63 ].

H 1c : Perceived instructional leadership that emphasizes competitive relationships will have a positive relationship with burnout. Instructional leadership that emphasizes competition among teachers may lead to a lack of feedback from colleagues and leaders during online instruction, which has been shown to contribute to burnout [ 64 ].

2.4 Burnout and psychological distress

Job burnout is a persistent, negative, and work-related psychological condition that can lead to turnover intention [ 65 ] (for example, among Chinese high school teachers during the pandemic), reduced productivity [ 66 ] (for example, among primary and secondary school teachers in English), and psychological distress such as anxiety and depression both in the general population [ 29 , 67 ] and among schoolteachers [ 68 ]. Teachers belong to a profession that is more likely to experience work-related stressors and psychological distress than other occupations [ 69 ]. As a group at high risk of job burnout [ 70 ], teachers have drawn extensive attention from researchers [ 14 , 71 , 72 ]. Shin et al. [ 38 ] used a three-wave longitudinal data to show that burnout among Korean middle and high school teachers predicted subsequent depressive symptoms. Similarly, in a scoping review, Agyapong et al. [ 39 ] found that teacher burnout could provoke symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

Based on the above facts, we propose the second research hypothesis: teachers’ burnout will be positively associated with psychological distress (Hypothesis 2). This hypothesis suggests that the experience of burnout in teachers is likely to result in psychological distress, given the high prevalence of psychological distress among teachers and the evidence linking burnout to subsequent depressive symptoms and other negative mental health outcomes.

2.5 The mediation of burnout between perceived instructional leadership and psychological distress

According to the SSO model, job stress does not necessarily lead directly to specific outcomes but may act on outcomes through a mediating mechanism (in this case, burnout) [ 42 ]. This mediating effect of burnout has been documented in various studies. For instance, Koeske and Koeske [ 73 ] found that emotional exhaustion mediated stressful events experienced by students and their physical and mental health symptoms. In two other studies, Dhir et al. [ 74 ] and Pang [ 75 ] found that social media fatigue mediated excessive media use and anxiety and depression as well as perceived information overload and emotional stress and social anxiety.

The independent variables from the above literature [ 73 – 75 ], including stressful events experienced by students, excessive media use, perceived information overload, and the three types of teachers’ perceived instructional leadership assessed in this study, are all prominent stressors. The dependent variables, such as anxiety and depression, represent different forms of psychological distress. Therefore, we hypothesize that burnout may mediate the relationship between teachers’ perception of instructional leadership (neglect of teaching autonomy, neglect of teaching competence, and emphasis on competitive relationships) and psychological distress (Hypothesis 3).

3.1 Participants

In this study, participants were recruited from Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province, China. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak in the city during October 2021, face-to-face teaching was cancelled for the city’s primary and secondary schools by the municipal government, beginning on November 3, 2021. After a month of strict restrictions, the outbreak was brought under control, and the campus reopened for face-to-face instruction. During this period, we conducted an online survey, with the assistance of the city’s education department, comprised of two waves. The first wave was conducted to investigate teachers’ perceived instructional leadership during school closures (Time 1: mid-November 2021). The second wave of the study examined teachers’ burnout and psychological distress within 2 to 3 weeks of resuming face-to-face teaching (Time 2: early-January 2022).

A priori sample size estimation was conducted using the Optimal Design Software [ 76 , 77 ]. With the support of the city’s education department, we were able to involve more than 100 schools in this survey. For the intended HLM analysis, given a cluster number of 100, a desired power of 0.8, an expected effect size of 0.30, and a significance level set at 5% (0.05), the a priori estimation yielded a requirement of five subjects per cluster (refer to S1 Fig ). Based on this outcome, we deduced that for cluster numbers exceeding 100, having 5 subjects per cluster would be adequate. This conclusion aligns with findings from previous studies [ 78 , 79 ]. These studies emphasized that to achieve adequate power, it’s more beneficial to increase the number of sampled clusters. Typically, sample sizes of up to 60 at the highest level and k+2 at the lower level (when there are k independent variables) are required.

This study was approved by the Jiangxi Association of Psychological Counselors (IRB ref: JXSXL-2020-J013), and with the assistance of the local education authority, data was collected via a hyperlink via convenience sampling. As participation was voluntary, participants were asked to include their email addresses if they wished to participate in a follow-up survey. There were 1,642 teachers who provided their email addresses and completed the longitudinal survey. To ensure data quality, we eliminated participants whose reported age was less than 18 and whose response time to all questions was less than 150 seconds. Additionally, we decided to exclude schools with participants of less than 4, considering the issue of representativeness and the required sample size [ 78 , 79 ]. As a final sample, 103 schools and 927 primary and secondary teachers were included, with a minimum of five teachers per school.

3.2 Measures

Demographic variables such as gender, teaching experience, subject of instruction and school type (primary school or secondary school), were collected. At Time 1, participants were asked to rate their perception of instructional leadership in the context of mandatory online instruction. At Time 2, participants were asked to report their levels of burnout and psychological distress over the preceding two weeks. The following subsections provide a detailed description of the measurement tools used in this study, and the items of the questionnaires are listed (see S1 – S3 Tables) in appendix.

3.2.1 Perceived instructional leadership.

To our knowledge, there isn’t a tool specifically designed to measure teachers’ perceptions of instructional leadership during periods of mandatory online teaching, such as those experienced during the pandemic. In the context of epidemic, a more directive leadership style is essential to guide teachers in the face of online teaching [ 54 ]. For the purpose of assessing teachers’ perceptions of this special form of instructional leadership at Time 1, we utilized the Psychological Need Thwarting Scale of Online Teaching (PNTSOT) developed by Yi et al. [ 80 ]. The alignment between perceived instructional leadership and the PNTSOT is illustrated in S2 Fig .

The PNTSOT was initially developed to assess the extent of psychological need thwarting during online teaching. In accordance with the CFA results in [ 80 ] (CFI = 0.966, NNFI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.09, and SRMR = 0.05) and revised results in [ 72 ] (CFI, NNFI ranged from 0.960 to 0.999; RMSEA and SRMR were both less than 0.09), these results indicate that PNTSOT has ideal factorial validity among primary and secondary schoolteachers.

In this study, the three subscales of the PNTSOT (autonomy, competence and relatedness thwarting) were considered as direct reflections of perceived instructional leadership (perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy, perceived school neglect of teaching competence and emphasis on competitive relationships) by teachers. For each question, a seven-item Likert-type scale was used, ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree". The three variables for psychological need thwarting were aggregated into school-level variables which corresponded to the three types of perceived instructional leadership. Through HLM, high-level data can be derived from the aggregation of low-level data. To establish the plausibility of the aggregation, the values of within-group agreement ( r wg ) were calculated and they were found to have adequate consistency ( r wg values for perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy, neglect of teaching competence, and emphasis on competitive relationships were 0.77, 0.74 and 0.82). Values of r wg between 0.70 and 0.79 indicated moderate agreement, and values of .80 and above indicated strong agreement [ 81 ]. As a result, it is was deemed reasonable to aggregate teacher-level data to school-level data and use them as independent variables for this study. The following will explain the correspondence between the three sub-dimensions of the PNTSOT and the three types of perceived instructional leadership.

Perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy refers to instructional leadership in which teachers felt that schools did not value their teaching autonomy and forced them to use specific teaching methods during online teaching. Perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy can be described by the autonomy thwarting subscale of the PNTSOT in terms of the following four items: “During online courses during the pandemic, I cannot decide for myself how I want to teach”, “During online teaching work during the pandemic, I feel there is pressure that affects my behavior and requires me to comply in a certain way”, “I have to follow a prescribed online teaching style during the pandemic” and “During the pandemic, I feel pressure from the external environment that limited me in choosing a particular online teaching style”. The higher the score, the more pronounced the perception of neglected teaching autonomy. Teachers perceptions of school neglecting teaching autonomy in this study demonstrated a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.79, McDonald’s ω = 0.79).

Perceived school neglect of teaching competence means that teachers believed their schools did not provide necessary online teaching training. They also paid little attention to their online teaching during the school closure period. Teachers felt that they had few opportunities to acquire more online teaching experiences. This sense of neglect can be described through competence thwarting in PNTSOT. The four items of competence thwarting included “There are some online teaching situations that make me feel incapable in my daily work environment during the pandemic” and “Due to the lack of training opportunities in my environment, I feel that I am not capable of performing online teaching tasks”. As a result of these items, it appears that schools may be neglecting teachers’ online teaching ability. A higher score indicates a higher level of perceived neglect of teaching competence. There is an acceptable degree of internal consistency from our data (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84, McDonald’s alpha = 0.86) for perceived school neglect of teaching competence.

Perceived school emphasis on competitive relationship refers to teachers’ belief that schools value teachers’ competition. This variable can be assessed using relatedness thwarting in the PNTSOT, in which the four items include “I feel disconnected from other colleagues and leaders when teaching online during the pandemic” and “I feel that my colleagues and leaders are jealous of me when I achieve good results in online teaching during the pandemic”. A higher score indicates a higher level of perception of school competitive relationships. Teachers perceptions of school competitive relationships in this study demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89, McDonald’s ω = 0.88).

3.2.2 Burnout.

Based on the fact that emotional exhaustion contributes most significantly to burnout [ 47 , 82 ], this study used the "Emotional Exhaustion Subscale" (8 items) of the Chinese version of the Primary and Secondary School Teachers’ Job Burnout Questionnaire (CTJBQ) [ 83 ] to assess teacher burnout at Time 2. A modified version of the CTJBQ scale was developed on the basis of the Maslach Burnout Inventory [ 82 ] to accommodate the cultural and linguistic background of mainland Chinese teachers. The CTJBQ scale includes subscales measuring emotional exhaustion, including "After a day at work, I feel exhausted" and "I feel that teaching has exhausted me emotionally and mentally." Based on a 7-point Likert-type scale, responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A higher score indicates a greater degree of job burnout. This study found that good internal consistency for burnout scores (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95, McDonald’s ω = 0.95).

3.2.3 Psychological distress.

In order to assess psychological distress at Time 2, this research utilized the Chinese version of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) developed by Chan et al. [ 84 ]. It has been demonstrated that the Chinese version of the DASS-21 scale has satisfactory psychometric properties [ 85 , 86 ]. In addition, recent studies have shown that DASS-21 scores are a valid indicator of general psychological distress [ 87 , 88 ]. A four-point scale was used to evaluate items on the DASS-21, with higher scores indicating more severe psychological distress. DASS-21 scores demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96, McDonald’s alpha = 0.96).

3.3 Data analysis strategy

In terms of data analysis, a descriptive analysis was first conducted to analyze the background characteristics of the participants. This was followed by Pearson correlation analysis to determine the means of all variables and their correlations. As a next step, HLM 6.08 software was used to analyze the data to test the hypotheses H 1 (H 1a , H 1b , H 1c ) and H 2 . HLM applies when observations in a study grouped in some way and the groups are selected randomly; therefore, it is commonly used to analyze nested data [ 79 ]. Model testing proceeded in four phases: null model, random intercepts model, means-as-outcomes model, intercepts- and slopes-as-outcomes model [ 89 ]. In this research, an intercepts-as-outcomes model was implemented, as we intended to examine the impact of school-level perceived instructional leadership on job burnout and psychological distress, rather than focusing on the moderating effect of variables. Based on this model, all the demographic variables investigated were treated as control variables except for subject of instruction, which is a category variable. Thus, more dummy variables were generated. Also, the variable for subject of instruction did not have a significant impact on the dependent variables or mediator variables and different subject teachers did not differ significantly in the means of these variables. The specific formulae for HLM are as follows:

Teacher level:

To verify H 3 , a bootstrapping method was applied with 5000 random samples in order to test the indirect mediating effect of job burnout. Specifically, this path is labeled as a 2-1-1 model, with these three numbers representing the levels of the independent variable, mediator variable, and dependent variable. Specifically, the independent variable was at the school level (level 2) and both the mediator and dependent variable were both at the teacher level (level 1) (burnout and psychological distress). The indirect effect was tested using model 4 of Hayes’ PROCESS macro [ 90 ] by placing all variables at the teacher level, as in [ 91 ]. As a result of using the bootstrapping method, the path coefficient and confidence interval were obtained. It can be concluded that a mediation effect is established if the confidence interval does not contain 0 [ 92 ].

HLM essentially serves as an extension of regression analysis [ 79 ]. Before delving into the primary statistical analysis, we rigorously assessed key assumptions tied to regression, including linearity, multivariate normality, and the absence of autocorrelation and multicollinearity. We employed Quantile-Quantile (QQ) plots (refer to S3 and S4 Figs) to evaluate linearity and multivariate normality, with the plots closely following a straight line, indicating an approximately linear and normal distribution of residuals. For the dependent variable "burnout", the Goldfield-Quandt test (statistic = 1.08, p = 0.22) and the Durbin-Watson test (DW statistic = 1.93, p = 0.26) confirmed the absence of heteroskedasticity and significant autocorrelation, respectively. Similarly, for "psychological distress", the Goldfield-Quandt test (statistic = 0.83, p = 0.98) and the Durbin-Watson test (DW statistic = 2.03, p = 0.71) yielded consistent results. Additionally, all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below 1.7, indicating no multicollinearity issues.

4.1 Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations

Before presenting the results of this study, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using diagonally weighted least squares estimation (DWLS) in light of the fact that DWLS is more suitable to the analysis of ordinal Likert-type scales [ 93 ]. The results of the CFA were presented in the appendix (see S4 and S5 Tables). Both the model fit (CFI = 0.985, NNFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.037, SRMR = 0.057) and the factor loadings (larger than 0.5) demonstrated satisfactory factorial validity in this study. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values (see Table 1 ) are generally greater than 0.5, indicating acceptable convergent validity.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.t001

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the study participants, including their gender, teaching experience, subject of instruction, and school type (primary or secondary). It is estimated that 81.4% of participants are females. Regarding teaching experience, 24.2% of the participants had less than 5 years of experience, while 25.8%, 18.3%, 9.9%, and 21.8% had 6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–20 years, and more than 20 years of experience, respectively. Among the participants, 35.8% taught Chinese, 33.1% taught mathematics, 12.7% taught English, 6.1% taught natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, geography), and 11.3% taught other subjects. Of the participants, 30.4% were from primary schools, and the remaining were from secondary schools.

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations (SD), and Pearson correlation coefficients for the variables included in the study. The correlation coefficients show a significant positive association between perceived instructional leadership (perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy, school neglect of teaching competence, emphasis on competitive relationships) and burnout and psychological distress ( r = 0.15 to 0.59).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.t002

Table 3 presents the results of HLM analysis. The null model with job burnout and psychological distress as outcome variables yielded ICC values of 0.035 and 0.005. Despite the small ICCs, HLM was not abandoned since additional dependence on higher-level grouping can arise after including explanatory variables into the models [ 94 ]. The use of multilevel analysis is not precluded by small ICCs [ 10 ]. Therefore, we continued to use HLM for our research objectives.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.t003

The results of the intercepts-as-outcomes model, displayed in Eqs ( 1 ) and ( 2 ), reveal that, after controlling for relevant variables, perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy has a significant positive impact on teachers’ job burnout ( β = 0.38, SE = 0.17, p = 0.02), which supports H 1a . However, perceived school neglect of teaching competence and emphasis on competitive relationships did not significantly impact burnout negatively, indicating that H 1b and H 1c were not supported. Additionally, the model shows that job burnout significantly and positively impacted psychological distress ( β = 0.18, SE = 0.01, p <0.01), supporting H 2 .

To test the third hypothesis, the mediating effect of job burnout between perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy and teachers’ psychological distress was examined based on the results of the first hypothesis. The bootstrapping method was applied with 5000 random samples, and the indirect effect was found to be significant [indirect effect = 0.046, 95% CI (0.031, 0.061)], which supports the proposed model wherein perceived school neglecting: teaching autonomy had a significant indirect effect on teachers’ psychological distress through job burnout. Therefore, it can be concluded that perceived school neglecting: teaching autonomy has a significant impact not only on teachers’ job burnout but also on their psychological distress, highlighting the importance of addressing this issue in schools.

5 Discussion

The educational landscape has been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with the closure of schools presenting a myriad of challenges for educators. A plethora of studies have underscored the multifaceted challenges teachers faced, ranging from the rapid adaptation to novel teaching technologies [ 95 ] to an escalation in workload [ 9 , 96 ]. Furthermore, a palpable lack of administrative support [ 10 , 28 , 32 ] has exacerbated the psychological distress experienced by educators. This research augments the existing body of knowledge by elucidating the ramifications of instructional leadership that overlooks the essence of teaching autonomy. Such neglect has been identified as a salient precursor to psychological distress, with burnout serving as a mediating factor. Notably, the study did not discern any significant effects stemming from the perceived neglect of teaching competence or the emphasis on competitive relationships within educational settings.

A pivotal revelation of this investigation is the detrimental impact of perceived institutional disregard for teaching autonomy during school closures. This adverse effect manifested prominently in the form of burnout and persisted even as educators transitioned back to traditional, in-person teaching modalities. This aligns with prior research which posits that diminished autonomy can be a catalyst for protracted burnout [ 27 , 36 , 60 , 61 ]. Conversely, some studies [ 36 , 97 ] have championed the protective role of perceived autonomy against burnout, particularly during the pandemic. These studies have enumerated several avenues to bolster teacher autonomy, encompassing flexibility in curriculum delivery, platform selection, and scheduling. Empirical evidence has consistently shown a positive correlation between teacher autonomy and pivotal outcomes such as motivation, instructional quality [ 98 ], empowerment [ 99 ] and job satisfaction [ 100 ], while inversely correlating with burnout [ 62 ]. The significance of autonomy in pedagogical settings cannot be overstated, especially given its pivotal role in teacher retention [ 100 ]. The deprivation of such autonomy, particularly in online pedagogical settings, can precipitate a cascade of negative outcomes, including diminished motivation, dissatisfaction, and pronounced burnout [ 62 ]. It’s noteworthy that the autonomy under scrutiny pertains to the latitude teachers had during online instruction, encompassing their discretion in pedagogical methodologies. The enduring impact of this neglect on educators’ mental well-being resonates with findings from Besser et al. [ 8 ] and Wakui et al. [ 101 ].

Contrastingly, this study’s findings diverge from the anticipated outcomes regarding the neglect of teaching competence and the emphasis on competitive relationships among educators. Such factors did not emerge as significant contributors to burnout. This observation is buttressed by findings from Huang et al. [ 102 ] and Yang and Huang [ 103 ], which highlight the plethora of resources available to educators during the pandemic, enabling continuous pedagogical skill enhancement. Consequently, it can be inferred that perceived school neglect of teaching competence might not be a salient determinant of burnout. Moreover, while competitive relationships can undoubtedly engender a less collegial environment, the virtual nature of instruction during the pandemic might have attenuated the impact of such competition on burnout. However, as educational institutions gravitate back to traditional teaching modalities, fostering a collaborative ethos among educators, underscored by mutual support and feedback, is paramount. This collaborative approach, coupled with the evident significance of autonomy, is pivotal for the holistic well-being of educators [ 104 ].

Further buttressing the findings of this study is the established linkage between educators’ burnout and psychological distress [ 38 , 39 , 71 , 72 ]. Burnout, typified by sustained negative affect related to pedagogical duties, can culminate in enduring psychological distress among educators [ 105 ]. This study’s findings also corroborate the mediating role of burnout between the perceived neglect of teaching autonomy and psychological distress, aligning with the conceptualization of burnout as a strain in SSO models [ 42 , 43 , 74 , 75 ]. Specifically, the study spotlighted the neglect of teaching autonomy by instructional leadership during school closures as a prominent stressor, culminating in protracted burnout and psychological distress.

Furthermore, the results derived from hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) underscored that perceived instructional leadership (perceived school neglect of teaching autonomy and competence, and emphasis on competitive relationships) did not have a direct bearing on psychological distress. Thus, this investigation substantiates the mediating role of burnout between perceived instructional leadership and educators’ psychological distress, aligning seamlessly with the SSO model.

Despite the valuable insights this study offers, there are several limitations to consider. Firstly, our sample was not randomly selected, which might constrain the generalizability of the findings to all middle and high school teachers in mainland China. Moreover, we did not include other teacher categories, such as kindergarten or university educators. Secondly, in order to efficiently access teachers’ perceived instructional leadership under pandemic conditions, we used a directive leadership as the special form of instructional leadership, which lead that our measurement of perceived instructional leadership is limited by epidemic. Future research would benefit from the development of a dedicated scale to assess perceived instructional leadership.

6 Conclusions

This study underscores the significant role that instructional leadership can play as a stressor for teachers over the long term in the pandemic, especially when it overlooks teaching autonomy. The findings indicate that when teachers perceive instructional leadership as neglecting their autonomy, it can have a profound and lasting impact on their job burnout. This, in turn, can detrimentally affect their mental well-being.

While strategies such as bolstering teacher resilience and ensuring more robust support from colleagues and managers are essential, our study also emphasizes the importance of enhancing teaching autonomy. Schools should prioritize giving teachers more ownership over their teaching methods, facilitated by sustainable leadership practices that emphasize life-long learning. Given the intricate nature of teaching, sustainability in the profession undoubtedly requires the autonomy that allows teachers to adaptively address students’ needs. This is especially true considering the challenges posed by the pandemic on teachers’ motivation and job satisfaction. As schools transition back to in-person teaching in the post-pandemic era, it becomes imperative to respect teachers’ pedagogical choices, grant them increased autonomy in the classroom, and nurture their self-efficacy and innovative capabilities. Such measures are crucial for the long-term mental health and overall well-being of teachers.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. strobe-checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s001

S1 Fig. The result of optimal design.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s002

S2 Fig. The corresponding relationship between perceived instructional leadership and PNTSIOT.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s003

S3 Fig. Q-Q Plot of residuals as burnout dependent variable.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s004

S4 Fig. Q-Q Plot of residuals as psychological distress dependent variable.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s005

S1 Table. Items of psychological need thwarting of online teaching scale.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s006

S2 Table. Items of emotional exhaustion subscale.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s007

S3 Table. Items of DASS-21.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s008

S4 Table. Model fit.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s009

S5 Table. Factor loadings of CFA.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s010

S1 File. Data source.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305494.s011

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 40. Hallinger P, Wang WC, Chen CW, Liare D. Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management rating scale. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015.

- 102. Huang R, Liu D, Tlili A, Yang J, Wang H. Handbook on facilitating flexible learning during educational disruption: The Chinese experience in maintaining undisrupted learning in COVID-19 outbreak. Beijing: Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University. 2020; 46.

The complexity of managing COVID-19: How important is good governance?

- Download the essay

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alaka m. basu , amb alaka m. basu professor, department of global development - cornell university, senior fellow - united nations foundation kaushik basu , and kaushik basu nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development jose maria u. tapia jmut jose maria u. tapia student - cornell university.

November 17, 2020

- 13 min read

This essay is part of “ Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world ,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacy of public health systems worldwide, casting a shadow that we could not have imagined even a year ago. As the fog of confusion lifts and we begin to understand the rudiments of how the virus behaves, the end of the pandemic is nowhere in sight. The number of cases and the deaths continue to rise. The latter breached the 1 million mark a few weeks ago and it looks likely now that, in terms of severity, this pandemic will surpass the Asian Flu of 1957-58 and the Hong Kong Flu of 1968-69.

Moreover, a parallel problem may well exceed the direct death toll from the virus. We are referring to the growing economic crises globally, and the prospect that these may hit emerging economies especially hard.

The economic fall-out is not entirely the direct outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic but a result of how we have responded to it—what measures governments took and how ordinary people, workers, and firms reacted to the crisis. The government activism to contain the virus that we saw this time exceeds that in previous such crises, which may have dampened the spread of the COVID-19 but has extracted a toll from the economy.

This essay takes stock of the policies adopted by governments in emerging economies, and what effect these governance strategies may have had, and then speculates about what the future is likely to look like and what we may do here on.

Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market.

It is becoming clear that the scramble among several emerging economies to imitate and outdo European and North American countries was a mistake. We get a glimpse of this by considering two nations continents apart, the economies of which have been among the hardest hit in the world, namely, Peru and India. During the second quarter of 2020, Peru saw an annual growth of -30.2 percent and India -23.9 percent. From the global Q2 data that have emerged thus far, Peru and India are among the four slowest growing economies in the world. Along with U.K and Tunisia these are the only nations that lost more than 20 percent of their GDP. 1

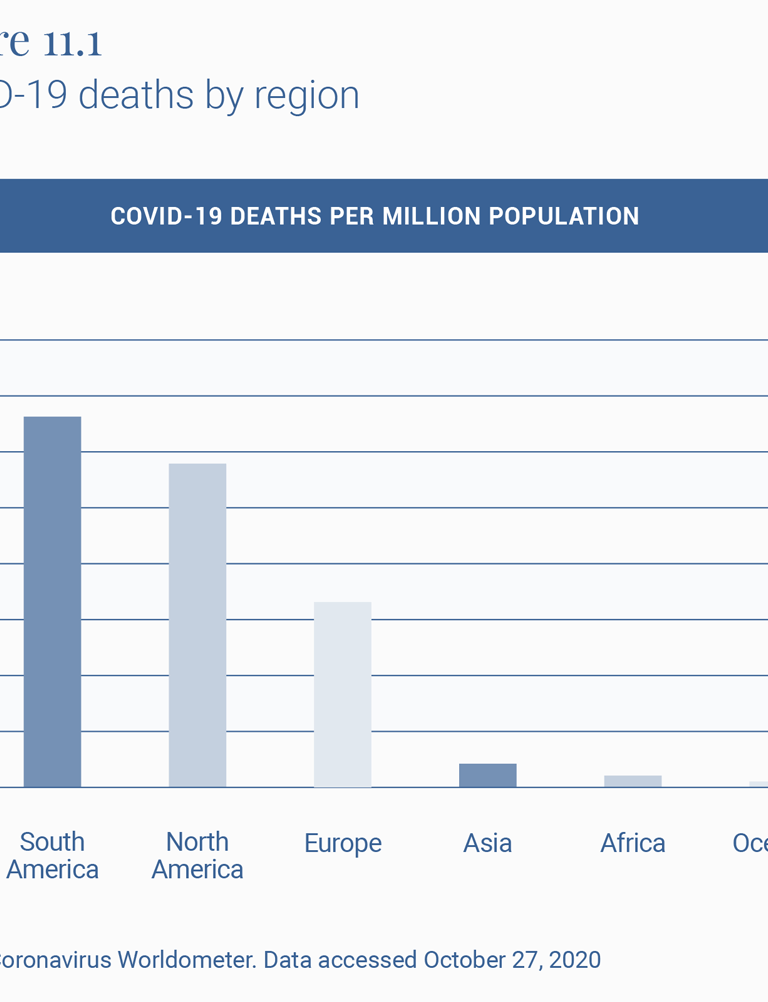

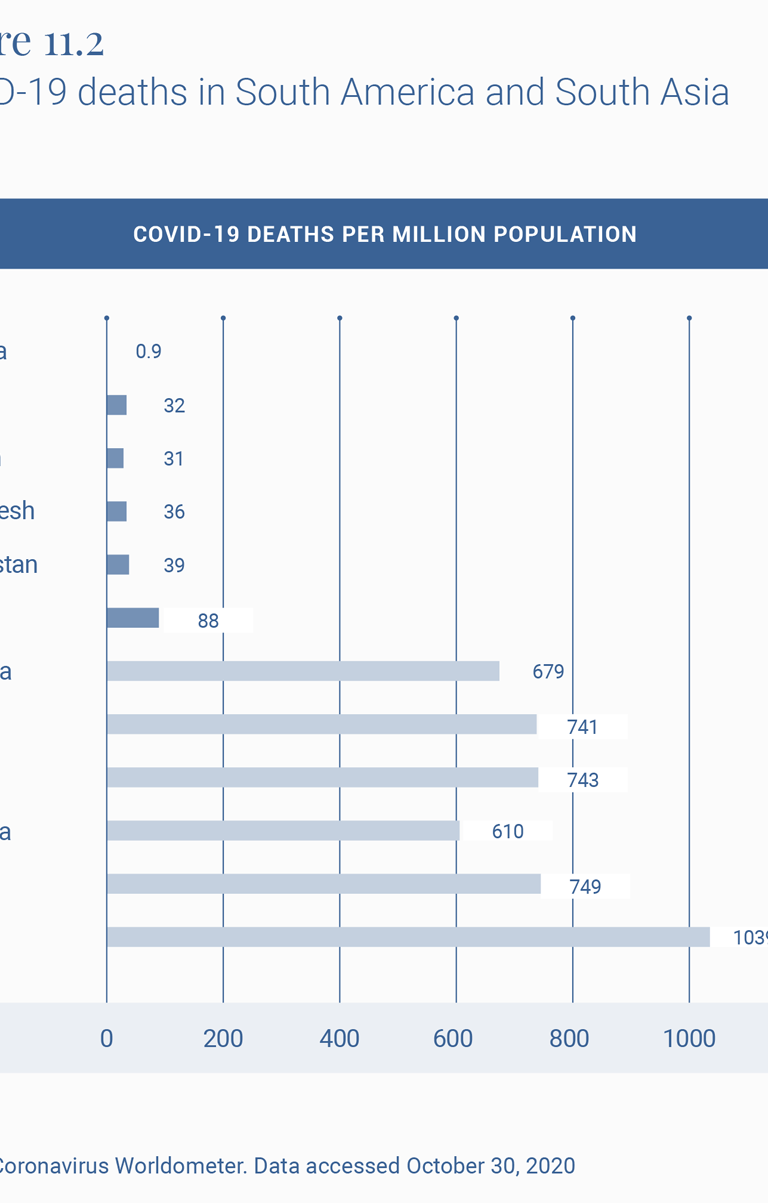

COVID-19-related mortality statistics, and, in particular, the Crude Mortality Rate (CMR), however imperfect, are the most telling indicator of the comparative scale of the pandemic in different countries. At first glance, from the end of October 2020, Peru, with 1039 COVID-19 deaths per million population looks bad by any standard and much worse than India with 88. Peru’s CMR is currently among the highest reported globally.

However, both Peru and India need to be placed in regional perspective. For reasons that are likely to do with the history of past diseases, there are striking regional differences in the lethality of the virus (Figure 11.1). South America is worse hit than any other world region, and Asia and Africa seem to have got it relatively lightly, in contrast to Europe and America. The stark regional difference cries out for more epidemiological analysis. But even as we await that, these are differences that cannot be ignored.

To understand the effect of policy interventions, it is therefore important to look at how these countries fare within their own regions, which have had similar histories of illnesses and viruses (Figure 11.2). Both Peru and India do much worse than the neighbors with whom they largely share their social, economic, ecological and demographic features. Peru’s COVID-19 mortality rate per million population, or CMR, of 1039 is ahead of the second highest, Brazil at 749, and almost twice that of Argentina at 679.

Similarly, India at 88 compares well with Europe and the U.S., as does virtually all of Asia and Africa, but is doing much worse than its neighbors, with the second worst country in the region, Afghanistan, experiencing less than half the death rate of India.

The official Indian statement that up to 78,000 deaths 2 were averted by the lockdown has been criticized 3 for its assumptions. A more reasonable exercise is to estimate the excess deaths experienced by a country that breaks away from the pattern of its regional neighbors. So, for example, if India had experienced Afghanistan’s COVID-19 mortality rate, it would by now have had 54,112 deaths. And if it had the rate reported by Bangladesh, it would have had 49,950 deaths from COVID-19 today. In other words, more than half its current toll of some 122,099 COVID-19 deaths would have been avoided if it had experienced the same virus hit as its neighbors.

What might explain this outlier experience of COVID-19 CMRs and economic downslide in India and Peru? If the regional background conditions are broadly similar, one is left to ask if it is in fact the policy response that differed markedly and might account for these relatively poor outcomes.

Peru and India have performed poorly in terms of GDP growth rate in Q2 2020 among the countries displayed in Table 2, and given that both these countries are often treated as case studies of strong governance, this draws attention to the fact that there may be a dissonance between strong governance and good governance.

The turnaround for India has been especially surprising, given that until a few years ago it was among the three fastest growing economies in the world. The slowdown began in 2016, though the sharp downturn, sharper than virtually all other countries, occurred after the lockdown.

On the COVID-19 policy front, both India and Peru have become known for what the Oxford University’s COVID Policy Tracker 4 calls the “stringency” of the government’s response to the epidemic. At 8 pm on March 24, 2020, the Indian government announced, with four hours’ notice, a complete nationwide shutdown. Virtually all movement outside the perimeter of one’s home was officially sought to be brought to a standstill. Naturally, as described in several papers, such as that of Ray and Subramanian, 5 this meant that most economic life also came to a sudden standstill, which in turn meant that hundreds of millions of workers in the informal, as well as more marginally formal sectors, lost their livelihoods.

In addition, tens of millions of these workers, being migrant workers in places far-flung from their original homes, also lost their temporary homes and their savings with these lost livelihoods, so that the only safe space that beckoned them was their place of origin in small towns and villages often hundreds of miles away from their places of work.

After a few weeks of precarious living in their migrant destinations, they set off, on foot since trains and buses had been stopped, for these towns and villages, creating a “lockdown and scatter” that spread the virus from the city to the town and the town to the village. Indeed, “lockdown” is a bit of a misnomer for what happened in India, since over 20 million people did exactly the opposite of what one does in a lockdown. Thus India had a strange combination of lockdown some and scatter the rest, like in no other country. They spilled out and scattered in ways they would otherwise not do. It is not surprising that the infection, which was marginally present in rural areas (23 percent in April), now makes up some 54 percent of all cases in India. 6

In Peru too, the lockdown was sudden, nationwide, long drawn out and stringent. 7 Jobs were lost, financial aid was difficult to disburse, migrant workers were forced to return home, and the virus has now spread to all parts of the country with death rates from it surpassing almost every other part of the world.

As an aside, to think about ways of implementing lockdowns that are less stringent and geographically as well as functionally less total, an example from yet another continent is instructive. Ethiopia, with a COVID-19 death rate of 13 per million population seems to have bettered the already relatively low African rate of 31 in Table 1. 8

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability.

The way forward

We next move from the immediate crisis to the medium term. Where is the world headed and how should we deal with the new world? Arguably, that two sectors that will emerge larger and stronger in the post-pandemic world are: digital technology and outsourcing, and healthcare and pharmaceuticals.

The last 9 months of the pandemic have been a huge training ground for people in the use of digital technology—Zoom, WebEx, digital finance, and many others. This learning-by-doing exercise is likely to give a big boost to outsourcing, which has the potential to help countries like India, the Philippines, and South Africa.

Globalization may see a short-run retreat but, we believe, it will come back with a vengeance. Nations that build walls to keep out goods, people and talent will get out-competed by other nations in the product market. This realization will make most countries reverse their knee-jerk anti-globalization; and the ones that do not will cease to be important global players. Either way, globalization will be back on track and with a much greater amount of outsourcing.

To return, more critically this time, to our earlier aside on Ethiopia, its historical and contemporary record on tampering with internet connectivity 9 in an attempt to muzzle inter-ethnic tensions and political dissent will not serve it well in such a post-pandemic scenario. This is a useful reminder for all emerging market economies.

We hope that human beings will emerge from this crisis more aware of the problems of sustainability. This could divert some demand from luxury goods to better health, and what is best described as “creative consumption”: art, music, and culture. 10 The former will mean much larger healthcare and pharmaceutical sectors.

But to take advantage of these new opportunities, nations will need to navigate the current predicament so that they have a viable economy once the pandemic passes. Thus it is important to be able to control the pandemic while keeping the economy open. There is some emerging literature 11 on this, but much more is needed. This is a governance challenge of a kind rarely faced, because the pandemic has disrupted normal markets and there is need, at least in the short run, for governments to step in to fill the caveat.

Emerging economies will have to devise novel governance strategies for doing this double duty of tamping down on new infections without strident controls on economic behavior and without blindly imitating Europe and America.

Here is an example. One interesting opportunity amidst this chaos is to tap into the “resource” of those who have already had COVID-19 and are immune, even if only in the short-term—we still have no definitive evidence on the length of acquired immunity. These people can be offered a high salary to work in sectors that require physical interaction with others. This will help keep supply chains unbroken. Normally, the market would have on its own caused such a salary increase but in this case, the main benefit of marshaling this labor force is on the aggregate economy and GDP and therefore is a classic case of positive externality, which the free market does not adequately reward. It is more a challenge of governance. As with most economic policy, this will need careful research and design before being implemented. We have to be aware that a policy like this will come with its risk of bribery and corruption. There is also the moral hazard challenge of poor people choosing to get COVID-19 in order to qualify for these special jobs. Safeguards will be needed against these risks. But we believe that any government that succeeds in implementing an intelligently-designed intervention to draw on this huge, under-utilized resource can have a big, positive impact on the economy 12 .

This is just one idea. We must innovate in different ways to survive the crisis and then have the ability to navigate the new world that will emerge, hopefully in the not too distant future.

Related Content

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

Anthony F. Pipa, Max Bouchet

Note: We are grateful for financial support from Cornell University’s Hatfield Fund for the research associated with this paper. We also wish to express our gratitude to Homi Kharas for many suggestions and David Batcheck for generous editorial help.

- “GDP Annual Growth Rate – Forecast 2020-2022,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/forecast/gdp-annual-growth-rate.

- “Government Cites Various Statistical Models, Says Averted Between 1.4 Million-2.9 Million Cases Due To Lockdown,” Business World, May 23, 2020, www.businessworld.in/article/Government-Cites-Various-Statistical-Models-Says-Averted-Between-1-4-million-2-9-million-Cases-Due-To-Lockdown/23-05-2020-193002/.

- Suvrat Raju, “Did the Indian lockdown avert deaths?” medRxiv , July 5, 2020, https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr183813#A1.

- “COVID Policy Tracker,” Oxford University, https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-tracker t.

- Debraj Ray and S. Subramanian, “India’s Lockdown: An Interim Report,” NBER Working Paper, May 2020, https://www.nber.org/papers/w27282.

- Gopika Gopakumar and Shayan Ghosh, “Rural recovery could slow down as cases rise, says Ghosh,” Mint, August 19, 2020, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/rural-recovery-could-slow-down-as-cases-rise-says-ghosh-11597801644015.html.

- Pierina Pighi Bel and Jake Horton, “Coronavirus: What’s happening in Peru?,” BBC, July 9, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-53150808.

- “No lockdown, few ventilators, but Ethiopia is beating Covid-19,” Financial Times, May 27, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/7c6327ca-a00b-11ea-b65d-489c67b0d85d.

- Cara Anna, “Ethiopia enters 3rd week of internet shutdown after unrest,” Washington Post, July 14, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/ethiopia-enters-3rd-week-of-internet-shutdown-after-unrest/2020/07/14/4699c400-c5d6-11ea-a825-8722004e4150_story.html.

- Patrick Kabanda, The Creative Wealth of Nations: Can the Arts Advance Development? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Guanlin Li et al, “Disease-dependent interaction policies to support health and economic outcomes during the COVID-19 epidemic,” medRxiv, August 2020, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.24.20180752v3.

- For helpful discussion concerning this idea, we are grateful to Turab Hussain, Daksh Walia and Mehr-un-Nisa, during a seminar of South Asian Economics Students’ Meet (SAESM).

Global Economy and Development

Caren Grown, Junjie Ren

August 19, 2024

Lesly Goh, Nataliya Langburd Wright

August 15, 2024

Robin Brooks, Peter R. Orszag, William E. Murdock III

8 Lessons We Can Learn From the COVID-19 Pandemic

BY KATHY KATELLA May 14, 2021

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it—and it may have changed us individually as well, from our morning routines to our life goals and priorities. Many say the world has changed forever. But this coming year, if the vaccines drive down infections and variants are kept at bay, life could return to some form of normal. At that point, what will we glean from the past year? Are there silver linings or lessons learned?

“Humanity's memory is short, and what is not ever-present fades quickly,” says Manisha Juthani, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist. The bubonic plague, for example, ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages—resurfacing again and again—but once it was under control, people started to forget about it, she says. “So, I would say one major lesson from a public health or infectious disease perspective is that it’s important to remember and recognize our history. This is a period we must remember.”

We asked our Yale Medicine experts to weigh in on what they think are lessons worth remembering, including those that might help us survive a future virus or nurture a resilience that could help with life in general.

Lesson 1: Masks are useful tools

What happened: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relaxed its masking guidance for those who have been fully vaccinated. But when the pandemic began, it necessitated a global effort to ensure that everyone practiced behaviors to keep themselves healthy and safe—and keep others healthy as well. This included the widespread wearing of masks indoors and outside.

What we’ve learned: Not everyone practiced preventive measures such as mask wearing, maintaining a 6-foot distance, and washing hands frequently. But, Dr. Juthani says, “I do think many people have learned a whole lot about respiratory pathogens and viruses, and how they spread from one person to another, and that sort of old-school common sense—you know, if you don’t feel well—whether it’s COVID-19 or not—you don’t go to the party. You stay home.”

Masks are a case in point. They are a key COVID-19 prevention strategy because they provide a barrier that can keep respiratory droplets from spreading. Mask-wearing became more common across East Asia after the 2003 SARS outbreak in that part of the world. “There are many East Asian cultures where the practice is still that if you have a cold or a runny nose, you put on a mask,” Dr. Juthani says.

She hopes attitudes in the U.S. will shift in that direction after COVID-19. “I have heard from a number of people who are amazed that we've had no flu this year—and they know masks are one of the reasons,” she says. “They’ve told me, ‘When the winter comes around, if I'm going out to the grocery store, I may just put on a mask.’”

Lesson 2: Telehealth might become the new normal

What happened: Doctors and patients who have used telehealth (technology that allows them to conduct medical care remotely), found it can work well for certain appointments, ranging from cardiology check-ups to therapy for a mental health condition. Many patients who needed a medical test have also discovered it may be possible to substitute a home version.

What we’ve learned: While there are still problems for which you need to see a doctor in person, the pandemic introduced a new urgency to what had been a gradual switchover to platforms like Zoom for remote patient visits.

More doctors also encouraged patients to track their blood pressure at home , and to use at-home equipment for such purposes as diagnosing sleep apnea and even testing for colon cancer . Doctors also can fine-tune cochlear implants remotely .

“It happened very quickly,” says Sharon Stoll, DO, a neurologist. One group that has benefitted is patients who live far away, sometimes in other parts of the country—or even the world, she says. “I always like to see my patients at least twice a year. Now, we can see each other in person once a year, and if issues come up, we can schedule a telehealth visit in-between,” Dr. Stoll says. “This way I may hear about an issue before it becomes a problem, because my patients have easier access to me, and I have easier access to them.”

Meanwhile, insurers are becoming more likely to cover telehealth, Dr. Stoll adds. “That is a silver lining that will hopefully continue.”

Lesson 3: Vaccines are powerful tools

What happened: Given the recent positive results from vaccine trials, once again vaccines are proving to be powerful for preventing disease.

What we’ve learned: Vaccines really are worth getting, says Dr. Stoll, who had COVID-19 and experienced lingering symptoms, including chronic headaches . “I have lots of conversations—and sometimes arguments—with people about vaccines,” she says. Some don’t like the idea of side effects. “I had vaccine side effects and I’ve had COVID-19 side effects, and I say nothing compares to the actual illness. Unfortunately, I speak from experience.”

Dr. Juthani hopes the COVID-19 vaccine spotlight will motivate people to keep up with all of their vaccines, including childhood and adult vaccines for such diseases as measles , chicken pox, shingles , and other viruses. She says people have told her they got the flu vaccine this year after skipping it in previous years. (The CDC has reported distributing an exceptionally high number of doses this past season.)

But, she cautions that a vaccine is not a magic bullet—and points out that scientists can’t always produce one that works. “As advanced as science is, there have been multiple failed efforts to develop a vaccine against the HIV virus,” she says. “This time, we were lucky that we were able build on the strengths that we've learned from many other vaccine development strategies to develop multiple vaccines for COVID-19 .”

Lesson 4: Everyone is not treated equally, especially in a pandemic

What happened: COVID-19 magnified disparities that have long been an issue for a variety of people.

What we’ve learned: Racial and ethnic minority groups especially have had disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white people in every age group, and many other groups faced higher levels of risk or stress. These groups ranged from working mothers who also have primary responsibility for children, to people who have essential jobs, to those who live in rural areas where there is less access to health care.

“One thing that has been recognized is that when people were told to work from home, you needed to have a job that you could do in your house on a computer,” says Dr. Juthani. “Many people who were well off were able do that, but they still needed to have food, which requires grocery store workers and truck drivers. Nursing home residents still needed certified nursing assistants coming to work every day to care for them and to bathe them.”

As far as racial inequities, Dr. Juthani cites President Biden’s appointment of Yale Medicine’s Marcella Nunez-Smith, MD, MHS , as inaugural chair of a federal COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. “Hopefully the new focus is a first step,” Dr. Juthani says.

Lesson 5: We need to take mental health seriously

What happened: There was a rise in reported mental health problems that have been described as “a second pandemic,” highlighting mental health as an issue that needs to be addressed.

What we’ve learned: Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh, MD, PhD , a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist, believes the number of mental health disorders that were on the rise before the pandemic is surging as people grapple with such matters as juggling work and childcare, job loss, isolation, and losing a loved one to COVID-19.

The CDC reports that the percentage of adults who reported symptoms of anxiety of depression in the past 7 days increased from 36.4 to 41.5 % from August 2020 to February 2021. Other reports show that having COVID-19 may contribute, too, with its lingering or long COVID symptoms, which can include “foggy mind,” anxiety , depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder .

“We’re seeing these problems in our clinical setting very, very often,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “By virtue of necessity, we can no longer ignore this. We're seeing these folks, and we have to take them seriously.”

Lesson 6: We have the capacity for resilience

What happened: While everyone’s situation is different (and some people have experienced tremendous difficulties), many have seen that it’s possible to be resilient in a crisis.

What we’ve learned: People have practiced self-care in a multitude of ways during the pandemic as they were forced to adjust to new work schedules, change their gym routines, and cut back on socializing. Many started seeking out new strategies to counter the stress.

“I absolutely believe in the concept of resilience, because we have this effective reservoir inherent in all of us—be it the product of evolution, or our ancestors going through catastrophes, including wars, famines, and plagues,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think inherently, we have the means to deal with crisis. The fact that you and I are speaking right now is the result of our ancestors surviving hardship. I think resilience is part of our psyche. It's part of our DNA, essentially.”

Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh believes that even small changes are highly effective tools for creating resilience. The changes he suggests may sound like the same old advice: exercise more, eat healthy food, cut back on alcohol, start a meditation practice, keep up with friends and family. “But this is evidence-based advice—there has been research behind every one of these measures,” he says.

But we have to also be practical, he notes. “If you feel overwhelmed by doing too many things, you can set a modest goal with one new habit—it could be getting organized around your sleep. Once you’ve succeeded, move on to another one. Then you’re building momentum.”

Lesson 7: Community is essential—and technology is too

What happened: People who were part of a community during the pandemic realized the importance of human connection, and those who didn’t have that kind of support realized they need it.

What we’ve learned: Many of us have become aware of how much we need other people—many have managed to maintain their social connections, even if they had to use technology to keep in touch, Dr. Juthani says. “There's no doubt that it's not enough, but even that type of community has helped people.”

Even people who aren’t necessarily friends or family are important. Dr. Juthani recalled how she encouraged her mail carrier to sign up for the vaccine, soon learning that the woman’s mother and husband hadn’t gotten it either. “They are all vaccinated now,” Dr. Juthani says. “So, even by word of mouth, community is a way to make things happen.”

It’s important to note that some people are naturally introverted and may have enjoyed having more solitude when they were forced to stay at home—and they should feel comfortable with that, Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think one has to keep temperamental tendencies like this in mind.”

But loneliness has been found to suppress the immune system and be a precursor to some diseases, he adds. “Even for introverted folks, the smallest circle is preferable to no circle at all,” he says.

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need a dose of humility

What happened: Scientists and nonscientists alike learned that a virus can be more powerful than they are. This was evident in the way knowledge about the virus changed over time in the past year as scientific investigation of it evolved.

What we’ve learned: “As infectious disease doctors, we were resident experts at the beginning of the pandemic because we understand pathogens in general, and based on what we’ve seen in the past, we might say there are certain things that are likely to be true,” Dr. Juthani says. “But we’ve seen that we have to take these pathogens seriously. We know that COVID-19 is not the flu. All these strokes and clots, and the loss of smell and taste that have gone on for months are things that we could have never known or predicted. So, you have to have respect for the unknown and respect science, but also try to give scientists the benefit of the doubt,” she says.

“We have been doing the best we can with the knowledge we have, in the time that we have it,” Dr. Juthani says. “I think most of us have had to have the humility to sometimes say, ‘I don't know. We're learning as we go.’"

Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Justin Stabley Justin Stabley

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/watch-live-tips-to-improve-time-management-under-quarantine

WATCH: 5 ways to manage your time during a pandemic

The novel coronavirus has infected nearly 2 million people and killed more than 130,000 worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. As countries around the world, including the United States, grapple with how to contain COVID-19, school closings, stay-at-home orders and other restrictions have upended daily life for many.

Watch the livestream in the player above.

Kamini Wood, a certified life coach, and the PBS NewsHour’s Amna Nawaz answered your questions about time management in a shifting world of working-from-home, unemployment and school closings.

What’s the best way to structure your day?

This pandemic has forced many to face a new normal and find a new routine. That often includes working with the rest of your family or roommates.

Wood emphasizes giving yourself “an element of grace” when going through your day-to-day life. That means giving yourself time to relax or find an activity you enjoy, and keep things in perspective.

She said it’s helpful to maintain at least a broader plan for your days, which means not staying in your pajamas — in an effort to feel like you are really starting your day — but not making things so structured “where every hour is planned out.”