- Numerical Reasoning

- Verbal Reasoning

- Inductive Reasoning

- Logical Reasoning

- Situational Judgement

- Mechanical Reasoning

- Watson Glaser Critical thinking

- Deductive reasoning

- Abstract reasoning

- Spatial reasoning

- Error checking

- Verbal comprehension

- Reading comprehension

- Diagrammatic Reasoning

- Psychometric tests

- Personality test

- In-Tray exercise

- E-Tray exercise

- Competency based assessment

- Game based assessments

- Analysis exercise

- Group exercise

- Presentation exercise

- Video interview

- Strengths based assessment

- Strengths based interviews

- Saville Assessment

- Talent Q / Korn Ferry

- Watson Glaser

- Criterion Partnership

- Test Partnership

- Cut-e / Aon

- Team Focus PFS

- Sova Assessment

Chapter 6: Case Study Exercises

A resource guide to help you master case study exercises

Page contents:

What is a case study exercise, how to answer a case study exercise, what skills does a case-study exercise assess, what questions will be asked in a case study exercise, case study exercise tips to succeed, key takeaways.

Case-study exercises are a very popular part of an assessment centre. But don't worry, with a bit of preparation and understanding, you can ace this part of the assessment.

Case study exercises are a popular tool used by employers to evaluate candidates' problem-solving skills, analytical thinking, and decision-making abilities. These exercises can be in the form of a written report, a presentation, or a group discussion, and typically involve a hypothetical business problem that requires a solution.

The case study presents the candidate with a series of fictional documents such as company reports, a consultant’s report, results from new product research etc. (i.e. similar to the in-tray exercise except these documents will be longer). You will then be asked to make business decisions based on the information. This can be done as an individual exercise, or more likely done in a group discussion so that assessors can also score your teamworking ability.

Before you start the exercise, it's important to carefully read and understand the instructions. Make sure you know what you're being asked to do, what resources you have available to you, and how your performance will be assessed. If you're unsure about anything, don't be afraid to ask for clarification.

Once you've read the case study, it's time to start analysing the problem. This involves breaking down the problem into its component parts, identifying the key issues, and considering different options for addressing them. It's important to approach the problem from different angles and to consider the implications of each possible solution.

During the exercise, you'll need to demonstrate your ability to work well under pressure, to think on your feet, and to communicate your ideas effectively. Make sure to use clear and concise language, and to back up your arguments with evidence and examples.

If you're working on a group case study exercise, it's important to listen to the ideas of others and to contribute your own ideas in a constructive and respectful way. Remember that the assessors are not only evaluating your individual performance but also how well you work as part of a team.

When it comes to presenting your solution, make sure to structure your presentation in a clear and logical way. Start with an introduction that sets out the problem and your approach, then move onto your analysis and recommendations, and finish with a conclusion that summarizes your key points. Make sure to keep to time and to engage your audience with your presentation.

A case study exercise is designed to assess several core competencies that are critical for success in the role you are applying for. There will be many common competencies that will be valuable across most roles in the professional world, these competencies typically include:

- Problem-Solving Skills: The ability to identify and analyse problems, and to develop and implement effective solutions.

- Analytical Thinking: The capacity to break down complex information into smaller parts, evaluate it systematically, and draw meaningful conclusions.

- Decision-Making Abilities: The ability to make well-informed and timely decisions, considering all relevant information and potential outcomes.

- Communication Skills: The capacity to convey ideas clearly and concisely, and to listen actively to others.

- Teamwork Skills: The ability to collaborate effectively with others, and to work towards a shared goal.

- Time Management: The capacity to prioritise tasks and to manage time effectively, while maintaining quality and meeting deadlines.

By assessing these competencies, employers can gain valuable insights into how candidates approach problems, how they think critically, and how they work with others to achieve goals. Ultimately, the aim is to identify candidates who can add value to the organisation, and who have the potential to become successful and productive members of the team.

Different companies will prioritise certain competencies; the original job description is a great place to look for finding out what competencies the employer desires and so will likely be scoring you against during the assessment centre activities.

The type of questions that may be asked can vary, but here are some examples of the most common types:

- Analytical Questions: These questions require the candidate to analyse a set of data or information and draw conclusions based on their findings. For example: "You have been given a dataset on customer behaviour. What insights can you draw from the data to improve sales performance?"

- Decision-Making Questions: These questions ask the candidate to make a decision based on a given scenario. For example: "You are the CEO of a company that is considering a merger. What factors would you consider when making the decision to proceed with the merger?"

- Group Discussion Questions: In a group case study exercise, candidates may be asked to work together to analyse a problem and present their findings to the assessors. For example: "As a team, analyse the strengths and weaknesses of our company's current marketing strategy and recommend improvements."

The questions are designed to test the candidate's problem-solving, analytical thinking, decision-making, and communication skills. It's important to carefully read and understand the questions, and to provide well-reasoned and evidence-based responses.

It has been known for employers to use real live projects for the case study exercise with sensitive information swapped for fictional examples.

Information from the case study exercise lends itself to be used as scene-setting for other exercises at the assessment centre. It is common to have the same fictional setting running through the assessment centre, to save time on having to describe a new scenario for each task. You will be told in each exercise if you are expected to remember the information from a previous exercise, but this is rarely the case. Usually the only information common to multiple exercises is the fictional scenario; all data to be used in each exercise will be part of that exercise.

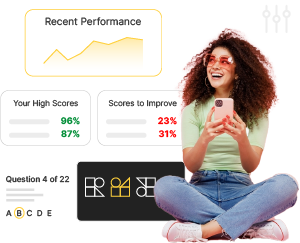

Start practising quality tests with a free account

Practice makes perfect

- Learn from detailed solutions

- Track your progress

Here are some key tips to help you prepare for and successfully pass a case study exercise at an assessment centre:

- Understand the Brief: Carefully read and analyse the case study brief, making sure you understand the problem or scenario being presented, and the information and data provided. Take notes and identify key issues and opportunities.

- Plan Your Approach: Take some time to plan your approach to the case study exercise. Consider the key challenges and opportunities, and identify potential solutions and recommendations. This will help you structure your thoughts and prioritise your ideas.

- Use Evidence: Use evidence from the case study, as well as your own research and knowledge, to support your ideas and recommendations. This will demonstrate your analytical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Stay Focused: During the exercise, stay focused on the task at hand and avoid getting sidetracked by irrelevant information or details. Keep the objective of the exercise in mind, and stay on track with your analysis and recommendations.

- Collaborate Effectively: If the case study exercise involves group work, make sure to communicate clearly and effectively with your team members. Listen actively to their ideas, and contribute constructively to the discussion.

- Be Confident: Have confidence in your ideas and recommendations, and be prepared to defend your positions if challenged. Speak clearly and confidently, and use evidence and data to support your arguments.

Here is the summary of what case-study exercises are and how to pass them:

- A case study exercise is a type of assessment where candidates are presented with a hypothetical business scenario and asked to provide solutions or recommendations.

- These exercises assess a range of competencies such as problem-solving, analytical thinking, decision-making, communication, teamwork, and time management.

- To pass a case study exercise, it's important to carefully read and understand the brief, plan your approach, use evidence to support your ideas, stay focused, collaborate effectively, be confident, and manage your time effectively.

Fully understanding the format of the exercise, taking practice case-study exercises and following our tips outlined above will drastically improve the chances of you standing out as a star candidate at the assessment centre.

Get 25% off all test packages.

Get 25% off all test packages!

Click below to get 25% off all test packages.

Case Study Exercise At Assessment Centres

A case study exercise is a practical assessment commonly used in the latter stages of recruitment for graduate jobs. One of several activities undertaken at an assessment centre , this particular type of exercise allows employers to see your skills in action in a work-based context.

What is a case study exercise?

A case study exercise consists of a hypothetical scenario, similar to something you’d expect to encounter in daily working life. You’ll be tasked with examining information, drawing conclusions, and proposing business-based solutions for the situation at hand.

Information is typically presented in the form of fictional documentation: for example, market research findings, company reports, or details on a potential new venture. In some cases, it will be verbally communicated by the assessor.

You may also have additional or updated information drip-fed to you throughout the exercise.

You could be asked to work as an individual, but it’s more common to tackle a case study exercise as part of a group, since this shows a wider array of skills like teamwork and joint decision-making.

In both cases you’ll have a set amount of time to analyse the scenario and supporting information before presenting your findings, either through a written report or a presentation to an assessment panel. Here, you’ll need to explain your process and justify all decisions made.

Historically, assessment centres have been attended in person, but as more companies look to adopt virtual techniques, you may take part in a remote case study exercise. Depending on the employer and their platform of choice, this could be via pre-recorded content or a video conferencing tool that allows you to work alongside other candidates.

What competencies does a case study exercise assess?

There are multiple skills under assessment throughout a case study exercise. The most common are:

Problem solving

In itself, this involves various skills, like analytical thinking , creativity and innovation. How you approach your case study exercise will show employers how you’re likely to implement problem-solving skills in the work environment.

Show these at every stage of the process. If working in a group, be sure to make a contribution and be active in discussions, since assessors will be watching how you interact.

If working solo, explain your process to show problem solving in action.

Communication

How you present findings and communicate ideas is a major part of a case study exercise, as are other communication skills like effective listening.

Regardless of whether you present as an individual or a group, make sure you explain how you came to your conclusions, the evidence they’re based on and why you see them as effective.

Commercial awareness and business acumen

Assessors will be looking for a broader understanding of the industry in which the company operates and knowledge of best practice for growth.

Standout candidates will approach their case study with a business-first perspective, able to demonstrate how every decision made is rooted in organisational goals.

Decision making

At the heart of every case study exercise, there are key decisions to be made. Typically, there’s no right or wrong answer here, provided you can justify your decisions and back them up evidentially.

Along with problem solving, this is one of the top skills assessors are looking for, so don’t be hesitant. Make your decisions and stick to them.

Group exercises show assessors how well you work as part of a team, so make sure you’re actively involved, attentive and fair. Never dominate a discussion or press for your own agenda.

Approach all ideas equally and assess their pros and cons to arrive at the best solution.

What are the different types of case study exercise?

Depending on the role for which you’ve applied, you’ll either be presented with a general case study exercise or one related to a specific subject.

Subject-related case studies are used for roles where industry-specific knowledge is a prerequisite, and will be very much akin to the type of responsibilities you’ll be given if hired by the organisation.

For example, if applying for a role in mergers and acquisitions, you may be asked to assess the feasibility of a buy-out based on financial performance and market conditions.

General case studies are used to assess a wider pool of applicants for different positions. They do not require specific expertise, but rather rely on common sense and key competencies. All the information needed to complete the exercise will be made available to you.

Common topics covered in case study exercises include:

- The creation of new marketing campaigns

- Expansion through company or product acquisition

- Organisational change in terms of business structure

- Product or service diversification and entering new markets

- Strategic decision-making based on hypothetical influencing factors

Tips for performing well in case study exercises

1. process all the information.

Take time to fully understand the scenario and the objectives of the exercise, identify relevant information and highlight key points for analysis, or discussion if working as part of a team. This will help structure your approach in a logical manner.

2. Work collaboratively

In a group exercise , teamwork is vital. Assign roles based on individual skill sets. For example, if you’re a confident leader you may head up the exercise.

If you’re more of a listener, you may volunteer to keep notes. Avoid conflict by ensuring all points of view are heard and decisions made together.

3. Manage your time

Organisational skills and your ability to prioritise are both being evaluated, and since you have a set duration in which to complete the exercise, good time management is key.

Remember you also need to prepare a strong presentation, so allow plenty of scope for this.

Make an assertive decision

There’s no right answer to a case study exercise, but any conclusions you do draw should be evidenced-based and justifiable. Put forward solutions that you firmly believe in and can back up with solid reasoning.

5. Present your findings clearly

A case study exercise isn’t just about the decisions you make, but also how you articulate them. State your recommendations and then provide the background to your findings with clear, concise language and a confident presentation style.

If presenting as a group, assign specific sections to each person to avoid confusion.

How to prepare for a case study exercise

It’s unlikely you’ll know the nature of your case study exercise before your assessment day, but there are ways to prepare in advance. For a guide on the type of scenario you may face, review the job description or recruitment pack and look for key responsibilities.

You should also research the hiring organisation in full. Look into its company culture, read any recent press releases and refer to its social media to get a feel for both its day-to-day activities and wider achievements. Reading business news will also give you a good understanding of current issues relevant to the industry.

To improve your skills, carry out some practice case study exercises and present your findings to family or friends. This will get you used to the process and give you greater confidence on assessment centre day.

Choose a plan and start practising

Immediate access. Cancel anytime.

- 20 Aptitude packages

- 59 Language packages

- 110 Programming packages

- 39 Admissions packages

- 48 Personality packages

- 315 Employer packages

- 34 Publisher packages

- 35 Industry packages

- Dashboard performance tracking

- Full solutions and explanations

- Tips, tricks, guides and resources

- Access to free tests

- Basic performance tracking

- Solutions & explanations

- Tips and resources

By using our website you agree with our Cookie Policy.

Access to 13 certificate programs, courses and all future releases

Personal Coaching and Career Guidance

Community and live events

Resource and template library

- Job Analysis: A Practical Guide...

Job Analysis: A Practical Guide [FREE Templates]

Did you know that job analysis is a powerful tool for improving job and organizational performance ? A proactive and strategic approach to job analysis will help your business thrive in the competitive market.

What is job analysis?

- Guide the recruitment and selection process: The analysis can inform the development of job postings, interview questions, and selection criteria to ensure candidates are well-suited for the role.

- Determine where jobs fit within the overall organizational structure: And understand how they relate to one another.

- Design and redesign jobs: Modifying job roles to improve efficiency, employee satisfaction, and adaptability to changing organizational needs.

- Support compensation and benefits decisions: Providing a basis for determining appropriate salary levels, benefits, and incentives based on job complexity and requirements.

- Duties and tasks: The type, frequency, and complexity of performing specific duties and tasks.

- Environment: Work environment, such as temperatures, odors, and hostile people.

- Tools and equipment: Tools and equipment used to perform the job successfully.

- Relationships: Relationships with internal and external people.

- Requirements: Knowledge, skills, and capabilities required to perform the job successfully.

| A collection of similar positions. | ‘Receptionist’ | |

| A set of duties, tasks, activities, and elements to be performed by a single worker. | Melinda, the receptionist who mostly works night-shifts | |

| Collections of tasks directed at general job goals. A typical job has 5 to 12 duties. | Hospitality activities for visitors | |

| Collections of activities with a clear beginning, middle, and end. A job has 30 to 100 tasks. | Welcoming guests and guiding them to the waiting room | |

| Clusters of elements directed at fulfilling work requirements. | Pushing the intercom button to open the door | |

| Smallest identifiable unit of work. | Answering the phone |

Types of job analysis data

- Work activities: Data on the specific activities that make up a job.

- Worker attributes: Data on the qualities that workers need to do the job.

- Work context: Data on the internal and external environment of the job.

The purpose of a job analysis

| HR uses the output of the job analysis as input for a job description. A is an internal document that specifies the requirements for a new position, including the required skills, role in the team, personality, and capabilities of a suitable candidate. Creating a job description using data from a job analysis helps you place the right people in the right roles. | |

| is the process of placing one or more jobs into a cluster or family of similar positions. Data from job analysis is critical in job classification because it considers the duties, responsibilities, scope, and complexity of a job. The goal is to set pay rates and use the information in . | |

| is the process of determining the relative rank of different jobs in an organization. The purpose is to create and . The rank of a job depends on the responsibility and duties assigned. For example, senior positions have higher performance and capability requirements. The job analysis helps understand these job characteristics. | |

| is the process of creating a job that adds value to the company and is motivating to the employee. One of the characteristics of a motivating job includes skill variety, i.e., the degree to which a job requires a broad array of skills. Job analysis helps you determine the skill variety of a job. | |

| HR can use the job analysis outcome to set the minimum qualifications or requirements of roles in the organization. This is also helpful in recruitment. | |

| The job analysis provides input for the of the individual performing the job. To evaluate an employee’s performance, you need to understand the role requirements first. Job analysis can determine these details. | |

| Job analysis forms the basis of the . Once you identify the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics, you can quickly identify training needs or skill gaps and train your employees. | |

| People and jobs should fit together. Job analysis is useful in identifying the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics required for a role, which you can then match with an internal or external hire. | |

| You can use job analysis to improve efficiency at work by analyzing activities and optimizing how people in the role perform them. | |

| Job analysis can identify hazardous behaviors and working conditions that increase the chance of accidents and injury, leading to a safer working environment. | |

| Job analysis helps plan for the workforce of the future. It helps identify knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics with future work demands. This enables the creation of a for a role or department. | |

| Federal and national law can apply to working conditions, health, hiring, training, pay, promotion, and firing employees. Job analysis can be a tool to ensure all activities in a role comply with the regulations. |

Why is job analysis important?

- Create detailed and accurate job postings that attract the skills and competencies you need.

- Improve decision-making when recruiting and hiring new employees by easily tracking candidates with the required qualities and qualifications for the job.

- Develop the job roles in line with evolving organizational needs and stay competitive in the changing business environment.

- Develop effective employee development plans by identifying the skills the employees lack to perform a job successfully.

- Plan and conduct more effective performance reviews based on a good understanding of the duties and nature of the job. It will improve employee performance and engagement.

- Determine the content of a job and its value to the company to offer fair compensation packages .

- Assess risks associated with a job and implement safety measures to avoid safety violations.

Job analysis methods

Critical incident technique (cit).

- A description of the context and circumstances leading up to the incident.

- The behaviors of the employee(s) during the incident.

- The consequences of the behaviors and their broader impact.

Task inventory (TI)

| Answering the intercom when the doorbell rings | 300/day | Medium | Low |

| Welcoming guests and guiding them to the waiting room | 120/day | Medium | Low |

| Providing guests with a drink | 80/day | Low | Low |

| Answering questions from visitors | 30/day | High | Medium |

| Managing expectations about waiting times | 30/day | Medium | High |

| Receiving and handling complaints | 6/day | High | Very high |

Functional job analysis (FJA)

- “Things” – Physical objects and tools involved in the job

- “Data” – Information, facts, and figures the employee works with

- “People” – Interactions and communications with others

- Threshold Traits Analysis

- Ability Requirements Scales

- Position Analysis Questionnaire

- Job Elements Method

Job analysis process steps

1. the job analysis purpose, 2. the job analysis method.

3. Gathering data

| Observational data is considered the most neutral form of data collection as it (supposedly) does not interrupt normal performance. The job analyst observes the person doing the job in real life or on video. Observational data can describe activities based on the chosen unit of analysis (see the Table above). Mere observation can already influence the way individuals conduct the job, a well-known example being the . | |

| Interviews are a key way to gather data, which can be used in combination with observational and questionnaire data. Based on the data, the job analyst asks specific questions. Interviews should be well-prepared and carefully conducted. Here again, the interviewer can focus on the different units of analysis to identify duties, tasks, activities, and work elements. | |

| The job analyst can administer a questionnaire with questions about job duties, responsibilities, equipment, work relationships, and work environment. The job analysis questionnaire can be self-designed or off-the-shelf, with the best-known example being the . | |

| The employee records their daily activities, the time spent on each, and the urgency of each activity. This log forms the basis for analyzing the job. |

4. Analysis

| 1. Answering the intercom | 4.3 | 0.5 | 49 | 0.1 |

| 2. Welcoming guests and seating them | 4.0 | 0.6 | 48 | 0.1 |

| 3. Providing refreshments to guests | 3.7 | 1.2 | 20 | 0.3 |

| 4. Answering questions from visitors | 3.2 | 1.6 | 32 | 0.3 |

| 5. Managing expectations about visitor waiting time | 2.5 | 2 | 12 | 0.6 |

Job analysis questionnaire

Job analysis examples, 1. sales job analysis example.

| Sales Representative | |

| Full-time employee | |

| Sales | |

| Mill Creek, Washington | |

| Level I | |

| Ensures current customers have the products and services they need. Identifies and pursues new markets and customer leads and pitches prospective customers. Follows a sales process that involves contacting prospects, following up, presenting products and services, and closing sales. Creates weekly, monthly, and quarterly sales reports and projections. Meets annual sales goals. | |

| – Generate leads – Create client lists – Contact prospects and negotiate with them – Follow up with prospects and existing customers – Close sales – Maintain client records – Create and present sales reports | |

| – Desktop office programs proficiency – Proficiency in CRM – Good customer service and interpersonal skills – Good communication skills | |

| – Reports directly to the national sales manager – No one reports to this position – Must attend yearly sales meeting | |

| – Bachelor’s degree in business, finance, marketing, economics, or a related field – At least five years of sales experience | |

| – Adapts to changing customer needs and expectations – Adapts to market changes – Can confidently make hundreds of cold calls a week – Able to work comfortably in a fast-paced environment | |

| – High-volume office setting – Sitting at a desk for most of the day – Travel to meet clients | |

| – Washington state driver’s license – National Association of Sales Professionals’ Certified Professional Sales Person – American Association of Inside Sales Professionals’ Certified Inside Sales Professional | |

| – Grow referral-based sales by 10% per year – Grow market channel penetration by 12% in the first year | |

| – Train at least one new junior sales associate |

2. Entry-level job analysis example

| Assistant Editor | |

| Full-time employee | |

| Book production | |

| Malibu, California | |

| Level III | |

| Assists the Editor-in-Chief and publisher in developing and delivering manuscripts. Reviews and proofreads manuscripts. Conceptualizes and pitches stories. Supports the Editor-in-Chief and coordinates with other departments, such as production and sales. Writes press releases and markets new books. Finds new authors. | |

| – Perform editorial duties to support the Editor-in-Chief – Find and contact new authors – Review and make changes to documents – Attend signings, readings, and book launches | |

| – Desktop publishing software proficiency – Good time management – Ability to multitask – Good interpersonal skills – Good communication skills | |

| – Reports to the Editor-in-Chief and publisher – No one reports to the Assistant Editor | |

| – Bachelor’s degree in English, literature, journalism, or a related field | |

| – Ability to read fast and identify errors and flow – Strong writing and reading skills – Ability to work on multiple projects simultaneously – Thriving on deadlines | |

| – Fast-paced office setting – Sitting at a desk for most of the time – Travel to book events 50% of the time | |

| – California state driver’s license – A member of the American Copy Editors Society | |

| – Reduce time to complete projects by 15% – Identify innovative programs to improve editing | |

| – Find at least ten new good authors every year – Train interns |

Job description vs job analysis

Weekly update.

Stay up-to-date with the latest news, trends, and resources in HR

- 1.3K shares

Erik van Vulpen

Related articles.

Payroll Audit: Checklist & How To Run It [Free Template]

Free PESTLE Analysis Templates and Actionable Guide

14 Compensation Philosophy Examples [+ Free Template]

New articles.

360 Recruitment: Your Ultimate 2024 Guide

People and Culture vs. HR: What’s the Difference?

54 Employee Feedback Survey Questions To Ask (In 2024)

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, are you ready for the future of hr.

Learn modern and relevant HR skills, online

- Numerical Reasoning

- Verbal Reasoning

- Inductive Reasoning

- Diagrammatic Reasoning

- Logical Reasoning

- Mechanical Reasoning

- Situational Judgement

- Deductive reasoning

- Critical thinking

- Spatial reasoning

- Error checking

- Verbal comprehension

- Reading comprehension

- Psychometric tests

- Personality test

- In-Tray exercise

- E-Tray exercise

- Group exercise

- Roleplay exercise

- Presentation exercise

- Analysis exercise

- Case study exercise

- Game based assessments

- Competency based assessment

- Strengths based assessment

- Strengths based interview

- Video interview

- Saville Assessment

- Talent Q / Korn Ferry

- Watson Glaser

- Test Partnership

- Clevry (Criterion)

- Criteria Corp

- Aon / Cut-e

- Sova Assessment

- Case Study Exercise

Case Study Exercises are commonly used in assessment centres, and often are unique to each company.

- Buy Full Practice Tests

- What is a Case Study exercise

Page contents:

How do case study exercises work.

Updated: 08 September 2022

Assessment Centre Exercises:

- Analysis Exercise

- Role Play Exercise

- Group Exercise

- Presentation Exercise

During an assessment day, it is common that you need to undertake a case study exercise. These exercises place candidates in real-life situations where they are tasked with solving problems faced by professionals in the real world. A case study typically involves being given various documents containing different information, either detailing a problem or situation that needs dealing with and requiring the candidate to resolve the issue at hand by formulating a plan. The problems or situation in the case study will be similar if not identical to problems encountered in the role itself. Candidates are also provided with background information to the elements of the case study, whether these be details of fictitious companies or sales figures, or other. The resolutions or solutions provided by the candidate regarding the problems are part of the assessment centre performance rating.

Why are case study exercises used?

Case study exercises are proficient predictors of role performance as they will resemble the work being done on the job. Therefore, case study exercises typically tilt highly on an assessment centre rating for candidates. Likewise, if a presentation exercise is required after the case study, based on details brought up during the case study, then your case study rating will likely impact your presentation exercise rating. Equally, this may manifest into the role play exercise which will do a similar thing to the presentation exercise – carrying on the case study situation. It is also entirely possible for the case study to be continued in a group exercise – which evaluate a candidate’s ability to work in a team. Given all this, you will need to perform well in the case study exercise to ensure a high rating.

What will the case study exercise be like?

As mentioned, the case study exercise you will be asked to perform will be similar to the type of work you will have to do in the role you are applying for.

The case study exercise may be purchased off the self from a test provider who specialize in the test style. This will mean that it won't be fully specific to the company you are applying to, but will be related to the role. Likewise, it can be designed bespoke if the organization requires specific role assessment. It's likely the larger and harder to get into the company is, the more tailored their exercises will be.

How can I prepare for the case study exercise?

Analysing technical documents and company reports may be helpful practice in preparation for a case study exercise. This will give a chance to familiarize yourself with the types of information typically found in these documents, and thus the case study exercise. Practicing case study exercises will also act as great preparation and they will provide a great insight into how they work and how they are to be handled. This will also prevent any unnecessary unknowns you could have before taking a case study exercise, as you will have already experienced how they work in practice.

We have an assessment centre pack which contains an example of the exercises you could face.

Why Do Employers Use Case Studies at Assessment Centers?

What to expect from a case study exercise, how to prepare for the case study exercise in 2024, how to approach a group exercise, how to approach a presentation, case study exercises at assessment centers (2024 guide).

Updated November 21, 2023

Should you be invited to be tested at an assessment center as part of an employer's recruitment process, one of the exercises you may face is a case study .

A case study exercise presents you with a scenario similar to what you would experience in the job you have applied for.

It will generally be accompanied by documents, emails or other forms of information.

You are asked to make business decisions based on the data you have been provided with, either alone or as part of a group of candidates.

A case study enables employers to assess your skill-base and likely performance in the job, providing them with a more rounded view of the type of employee you would be and the value you would bring to the company.

Commonly used in the finance, banking, legal and business management industries, the main advantage to employers of using case study exercises is to see candidates in action, demonstrating the skills they would be expected to use at work.

The skills assessed when participating in a case study exercise will vary depending on the employer, the industry and the job applied for, but may include:

- Analytical skills

- Strategic thinking

- Decision making

- Problem-solving

- Communication

- Stress tolerance

- The ability to assimilate information quickly and effectively

- Organisational skills

- Situational judgment

- Commercial awareness

- Time management

- Team working

- Knowledge pertinent to the industry or job, for example, marketing skills

Despite the skills that the employer is actively assessing, such as those mentioned above, success in a case study exercise relies on your ability to:

- Interpret and analyze the information provided

- Reach a decision

- Use commercial awareness

- Manage your time

- Communicate well

Practice Case Study Exercises with JobTestPrep

There are generally two types of case study exercise that you may face as part of a selection process:

- Subject-related case studies pertinent to the job you are applying for and the related industry

- General case studies that assess your overall aptitude and skills

The actual scenario of the case study exercise you face will vary, but examples of typical case studies include:

- Expanding a team or department

- Deciding whether an acquisition or merger is advisable

- Investigating whether to begin a new product line

- Re-organisation of management structure

- The creation of an advertising campaign

- Responding to negative publicity

- Choosing from three business proposals

- Developing a social media presence

Prepare for Case Study Exercises with JobTestPrep

For example: You are presented with the scenario of an IT company that went through an expensive re-brand one year ago. At that time, the company moved to bigger premises in a better area, and two new teams of developers were recruited to work with two new clients. The IT company has recently lost one of those clients and is facing increasing costs as the rent is raised for their premises. The company's directors have concluded that they must make one of the following changes: Make staff redundancies and offer the chance to several employees to change to part-time hours Move to less expensive premises in a less desirable area Combine a move to a flexible working business model where employees work part of the week from home and desk-share in the office along with a physical move to smaller premises in the same area where the IT company is currently based

You are asked to advise the directors on which change would provide the greatest benefit.

Here is another example:

A multi-national environmental testing organization buys out an oil-testing laboratory. A gap test is carried out on whether: The oil-testing lab should be brought in line with the rest of the organization concerning its processes, customer interface, and testing procedures The oil-testing lab should be closed down and its clients absorbed into the rest of the organization The oil-testing lab should be allowed to continue as it is, but new processes put in place between it and the larger organization

You are asked to consider the findings of the gap test and suggest the best course of action.

Just as you would prepare before a job interview, it is always in your best interests to prepare before facing a case study exercise at an assessment center.

Step 1 . Do the Research

There is a whole range of research you can look into to prepare yourself for the case study exercise:

- The job description and any other literature or documents forwarded to you

- The employer's website and social media

- Industry related news stories and developments

Any of the above should provide you with a better understanding of the job you have applied for, the industry you will work within, and the culture and values of the employer.

Step 2 . Use Practice Case Studies

Practicing case study exercises in the run-up to the assessment day is one of the best ways you can prepare for the real thing.

Unless the employer provides sample case studies on their website or as part of their recruitment pack, you will not know the exact format that the exercise will take; however, you can build familiarity with the overall process of a case study through practice.

You can find plenty of practice case study exercises online. Most of these come at a cost, but you may also be able to find free sample case studies too.

For case study resources at a cost, have a look at JobTestPrep .

For two free sample case study exercises, you might like to visit Bain & Company's website .

Scroll down to the Associate Consultant Case Library. Europa also offers an extensive and detailed sample case study .

Step 3 . Timed Practice

Once you have sourced one or more practice case studies, take the opportunity to practice to a time limit.

The case study may come with a time limit, or the employer may have already told you how long you will have to complete the real case study exercise on the day.

Alternatively, set your reasonable time limit.

Timed practice will improve your response time and explain exactly how much time you should allocate to each stage of the case study process.

Step 4 . Improve Your Reading Comprehension

One skill that is key to handle a case study exercise successfully is your reading comprehension, that is, your ability to understand written information, interpret it and describe it in your own words.

In the context of a case study, this skill will help you to assimilate the information provided to you quickly, analyze it and ultimately reach a decision.

In the run-up to your assessment day, put aside time to improve your reading comprehension by reading a wide variety of material and picking out the key points of each passage.

You might find it especially helpful to read professional journals and news articles related to the job you have applied for and the related industry.

Try to improve the speed at which you can read but still retain information too. This will prove helpful during the real case study exercise.

Step 5 . Practice Mental Math

The case study exercise may include prices, area measurements, staff numbers, salaries and other numeric values.

It is important that you can complete basic mental math calculations, such as multiplication and percentages.

Practice your mental math using puzzle books, online math resources and math problems that you create yourself.

You can find plenty of online business math resources, for example:

- The University of Alabama at Birmingham Math and Business Guide

- Money Instructor

- Open Textbook Library

If you need to prepare for a number of different employment tests and want to outsmart the competition, choose a Premium Membership from JobTestPrep . You will get access to three PrepPacks of your choice, from a database that covers all the major test providers and employers and tailored profession packs.

Get a Premium Package Now

Top Tips for Approaching Case Study Exercises

Now that you have prepared yourself, you can further improve your chances of a successful outcome by following our top tips on approaching case study exercises on the day.

Read the Information Carefully

Read all of the information provided as part of your case study exercise to understand what is being asked of you fully.

Quickly identify the key points in the task and the overall decision you have been asked to make, for example:

- Has the exercise provided you with a choice of outcomes you must decide between, or must you create the outcome yourself?

- What information do you need to make your decision?

- Are there calculations involved in the task?

- What character are you playing in the task (for example, HR manager or business consultant) and what are that character's motivations?

- Who is your character presenting their response to? Company directors, client or HR department?

Prioritize the Information

Prioritize the information by importance.

Which pieces of information are most pertinent to the task, and what key data do they provide?

Can any of the information be dismissed? Does any of the information contradict or sit in conflict with others?

Divide Up the Tasks and Allocate Time

You will generally be asked to come to a conclusion or advise a course of action regarding your case study exercise; however, you may have to carry out several tasks to arrive at this result.

Once you have read through the information, plan out what tasks the exercise will entail and allocate time for each one.

Do Not Be Distracted by Finding the Only 'Right' Answer

Where you are provided with several outcomes, and you must decide on one, do not assume that anyone's outcome is the only right answer to give.

It may be that any of the outcomes could be correct if you can sufficiently support your decision from the information provided.

Keep the Objective in Focus

- What does the task ask you to do?

- Must you choose between three business acquisitions?

- Are you providing advice on whether or not to invest?

- Are you putting together a plan for a staff redundancy situation?

Keep the objective of the case study exercise in mind at all times.

Support Your Decision With Evidence

The conclusion you come to may seem obvious to you, but you must be able to support your decision with evidence.

Why would it be better for the company to invest in property overstock? What is the benefit to the company of entering a new market?

It is not sufficient to know which outcome would be the best. As in the real-life business world, you must be able to support your claims.

If you are assessed as part of a group, you must arrive at a conclusion as a team and bear in mind your strengths.

For example, do you have a good eye for detail and would therefore be suited to the analytical part of the task?

Arrive at a list of tasks together and then assign the tasks to different members of the group.

Please make sure you contribute to the group discussions but do not dominate them.

Group assessments are generally used by employers who place value on leadership, teamwork and communication skills.

If you are asked to present your findings or conclusion as part of a case study exercise, bear in mind to whom the task has asked you to make that presentation.

For example, a business client or a marketing manager.

Make sure that you can fully support the reasons that you came to your conclusion.

If you are presenting as a group, make sure that each group member has their role to play in the presentation and that everyone knows why the group came to that conclusion.

Act professionally to suit the job you have applied for. Be polite, confident and well-spoken.

Case study exercises are just one of the many methods that employers use to assess job applicants, and as with any other aspect of the selection process, they require a degree of consideration and preparation.

The best way to improve your chances of a successful outcome and reduce exam tension is to research the job and the industry, practice case study exercises and improve your skills.

You might also be interested in these other Psychometric Success articles:

Or explore the Aptitude Tests / Test Types sections.

Tips to pass a case study exercise

What is a case study exercise.

Depending on the job position, case study exercises may be used by some companies to assess the capabilities of a candidate and determine how well they will perform after being selected. A case study exercise is one of many exercises employed in an assessment center. The individuals participating in the exercise may be put in a simulated situation that they might face in real life on the job. Their response to the exercise will help determine the way they will behave while confronting the same problems in reality. Thus, analysis of this behavior can help in evaluating if the candidate’s skillset is suited for the job.

In a case study exercise, the candidates are usually required to make decisions based on a set of information supplied to them. This information may relate to some aspect of the profession and may include financial reports, market studies or competition analysis. The exercise may be allotted to potential employees individually or they may participate as a group. Candidates may be asked to propose a plan of action based on their decision as a written report or a presentation. A group of assessors usually score the performance of the candidates.

Case study exercises usually help evaluate how a candidate analyzes information, the logical approach behind their decision making process and the way they tackle difficult situations. They may help exhibit creativity, intuitiveness and out of box thinking of the candidates. The scenarios presented to the candidates in case study exercises are usually based on a few core subjects, including:

- Finding the feasibility and profitability of introducing a new product or service.

- Merger, acquisition and joint venture related managerial decisions.

- Business model revamping and re-strategizing.

- Evaluation of annual reports and accessing causes of their profitability and loss.

- Prioritizing tasks and finding possible solutions within a given deadline.

Besides these, some other scenarios may be simulated depending on the specific skills required for the job and the industry in which the candidate wishes to enter.

Tips to pass a Case Study

The performance of a candidate in case study exercise will have a major role in their selection. Though the exercises can be complicated, a few tips can help the candidates master the same.

- Point of Perspective

The point of perspective while analyzing the information is the main force in driving the decision-making process. For example, in a law firm’s case study exercise, a decision that has been taken by a prosecutor will be different from the one taken by a defendant. It is of utmost importance that a person keeps in mind the role they are assigned while deciding on the right plan of action. In case of a group case study exercise, the candidate should consider the individuals associated with their role in the given scenario and reflect on the interaction and impact they may have in the analysis of the given situation and the decision-making process. If an individual in a client’s role is also a part of the environment, the same should be factored into the perspective.

- Information Analysis and Prioritization

Case study exercises may help evaluate the analytical abilities of the individuals and the candidates may be supplied with information related to multiple aspects of the role. The same should be analyzed by the candidate to determine which information should be kept and which should be discarded. There may be multiple conflicting issues to be addressed in a case study simulation, and recognition and prioritization of the consequential ones out of these are necessary.

- Time Management

A case study exercise may be timed to test the deadline meeting and stress management capabilities of the candidate. In such a scenario, the candidate should plan their approach to solving the case study based on the time available. Time conservation should be a priority and only relevant information should be analyzed while the irrelevant one should be discarded. Focus should be on finding the most probable solution and trying to justify an unfavorable solution in order to be avoided.

- Arriving at a decision

Before arriving at a final decision, all possible solutions should be considered. Each of these should be analyzed for their feasibility, the time they will require to be implemented, the costs associated with them and their effectiveness at solving the problem. Irrelevant or unfeasible solutions may be marked off one by one depending on the role the candidate is having and the objective they are aiming to fulfill. In some cases, there may be no correct solution and multiple approaches may seem possible for solving the same set of problems. The solution and its implementation should have a solid foundation to be proposed and a plan of action should be implemented.

- Communicate Effectively

In a case study exercise, the candidate may be asked to present their analysis and findings. While presenting the same, the presenter should communicate the logic and motivation behind their decision, and justify the same. The candidate may be subjected to questioning by the assessors to probe their confidence and decision-making ability. It is essential for the candidate to remain calm and assertive while responding, using clear voice with audible pitch, hand gestures and expressions. If the candidate is a part of a group case study exercise, they should participate actively without trying to dominate the proceedings. They should share their viewpoints and lend valuable input to enable the group to arrive at a decision.

- Practice Beforehand and Gather Information

Practicing mock case study exercises regularly can help a candidate ace the same when appearing in an assessment center. There are multiple case study exercise examples available online as well as by some institutes to help the candidates prepare for assessment centers. Utilizing the same can familiarize a candidate with the case study exercise.

Finally, gathering information regarding the organization, job profile and any data that might be presented in the case study as well as the possible simulation exercise roles can help the candidate be aware of the possible scenarios beforehand. This may enable them to practice the case study exercise and be well-prepared for it.

How can Assessment-Training.com help you ace your job interview, assessment and aptitude test?

Assessment-Training.com is your number 1 online practice aptitude test and assessment provider. Our aim is to help you ace your assessment by providing you practice aptitude tests that mimic the tests used by employers and recruiters. Our test developers have years of experience in the field of occupational psychology and developed the most realistic and accurate practice tests available online. Our practice platform uses leading-edge technology and provides you feedback on your scores in form of test history, progress and performance in relation to your norm group.

The Assessment-Training.com data science team found that through practice, candidates increased their scoring accuracy and went into their assessments more confident. Remember, you need to practice to make sure you familiarize yourself with the test formats, work on your accuracy and experience performing under time-pressure.

All Aptitude Tests Package

- 206 Aptitude Tests

- 3281 Aptitude Test Questions

- One-off Payment

Welcome to Assessment-Training.com

We are here to help you pass your tests and job interviews. Before you start practicing, please complete your full profile for our Personal Progression System (PPS) to run smoothly. Track your progress, and pass your tests easily. Prepare to succeed!

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Chapter 2—Performance Management Process Learning Objectives

Related Papers

Journal of Business & Economics …

Barbara Alston

Proceedings of Oxford Business and Economics …

Ninette A Appiah

The main focus is on performance management practices and its improvement to enhance the performance of employees

Balboa Mohamed

Journal of Organizational Behavior

Herman Aguinis

Texas State PA Applied Research Projects

OLUBIYI OLAYIWOLA S

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.2 Job Analysis

Job Analysis is a systematic process used to identify and determine, in detail, the particular job duties and requirements and the relative importance of these duties for a given job. It allows HR managers to understand what tasks people actually perform in their jobs and the human abilities required to perform these tasks. It is often called the “bedrock” of HRM practices. Job analysis aims to answer questions such as:

- What are the specific elements of the job?

- What physical and mental activities does the worker undertake?

- When is the job to be performed?

- Where is the job to be performed?

- Under what conditions is it to be performed?

A major aspect of job analysis includes research, which may mean reviewing job responsibilities of current employees, researching job descriptions for similar jobs with competitors, and analyzing any new responsibilities that need to be accomplished by the person with the position.

Job Analysis Competencies

- Conduct a job analysis using an objective methodology that is appropriate for the purpose for which the job analysis is conducted.

- Implement job enrichment, job enlargement, and job re-design initiatives when deemed appropriate.

Source: HRPA Professional Competency Framework (2014) , pg. 13. © HRPA, all rights reserved.

For HRM professionals, the job analysis process results lead to job design, work structure and process engineering, as well as team and department structure. The data collected informs a multitude of HR policies and processes. For this reason, job analysis is often referred to as the ‘building block’ of HRM.

How HRM Uses Job Analysis

Here are some examples of how the results of job analysis can be used in HRM:

- Production of accurate job postings to attract strong candidates;

- Identification of critical knowledge, skills, and abilities required for success to include as hiring criteria;

- Identification of risks associated with the job responsibilities to prevent accidents;

- Design of performance appraisal systems that measure actual job elements;

- Development of equitable compensation plans;

- Design training programs that address specific and relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities.

The Job as Unit of Analysis

Any job, at some point, needs to be looked at in detail in order to understand its important tasks, how they are carried out, and the necessary human qualities needed to complete them. As organizations mature and evolve, it is important that HR managers also capture aspects of jobs in a systematic matter because so much relies on them. If HRM cannot capture the job elements that are new and those that are no longer relevant, it simply cannot build efficient HRM processes.

Take the job of university or college professor, for example. Think of how that job has changed recently, especially in terms of how professors use technology. Ten years ago, technology-wise, a basic understanding of PowerPoint was pretty much all that was required to be effective in the classroom. Today, professors have to rely on Zoom, Moodle, and countless other pedagogical platforms when they deliver their courses.

These changes point to a profound change in the job. It is critical that this change be captured by the organization’s HR department in order for the organization to achieve their educational mission. With this information, departments can now select professors based on their level of technological savvy, develop training programs on various platforms, and evaluate/reward those professors who are embracing the technological shift, etc.

While job analysis seeks to determine the specific elements of each job, there are many studies that have looked at how jobs are evolving in general . These mega trends are interesting because they not only point towards new characteristics of jobs but also towards an acceleration in the rate of change.

For example, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has just begun to make its impact on the world of work. In the next decade, many tasks will be replaced and even enhanced by algorithms. Project yourself, if you can, 50 years from now. Do you think that transportation companies will rely on truck drivers? Autonomous vehicles are already a reality, this promises to be incredibly efficient. Do you think that customer service representatives will be required? We are already having conversations with voice-recognition automated systems without realizing it. Let’s push this to more sophisticated jobs: medical doctors. The diagnosis of illness requires a vast amount of knowledge and, in the end, judgment. Who would bet against the ability of computers able to process billions of bits of information per second not to outperform the average doctor? Bottom line: the AI revolution is not coming, it is already here.

Determine Information Needed

The information gathered from the job analysis falls into two categories: the task demands of a job and the human attributes necessary to perform these tasks. Thus, two types of job analyses can be performed: a task-based analysis or a skills-based analysis.

Task-based job analysis

This type of job analysis is the most common and seeks to identify elements of the jobs. Tasks are to be expressed in the format of a task statement. The task statement is considered the single most important element of the task analysis process. It provides a standardized, concise format to describe worker actions. If done correctly, task statements can eliminate the need for the personnel analyst to make subjective interpretations of worker actions. Task statements should provide a clear, complete picture of what is being done, how it is being done and why it is being done. A complete task statement will answer four questions:

- Performs what action? (action verb)

- To whom or what? (object of the verb)

- To produce what? or Why is it necessary? (expected output)

- Using what tools, equipment, work aids, processes?

When writing task statements, always begin each task statement with a verb to show the action you are taking. Also, do not use abbreviations and rely on common and easily understood terms. Be sure to make statements very clear so that a person with no knowledge of the department or the job will understand what is actually done. Here are some examples of appropriate task statements:

- Analyze and define architecture baselines for the Program Office

- Analyze and support Process Improvements for XYZ System

- Analyze, scan, test, and audit the network for the Computer Lab

- Assess emerging technology and capabilities for the Computer Lab

- Assist in and develop Information Assurance (IA) policy and procedure documents for the Program Office

- Automate and generate online reports for the Program Office using XYZ System

- Capture, collate, and report installation safety issues for XYZ System

- Conduct periodic facility requirements analysis for the Program Office

- Copy, collate, print, and bind technical publications and presentation materials for the Program Office

Competency-based job analysis

A competency-based analysis focuses on the specific knowledge and abilities an employee must have to perform the job. This method is less precise and more subjective. Competency-based analysis is more appropriate for specific, high-level positions.

Identify the Source(s) of Data

For job analysis, a number of human and non-human data sources are available besides the jobholder themselves. The following can be sources of data available for a job analysis.

Determine Methods of Data Collection

Determining which tasks employees perform is not easy. The information provided helps in decision making, must be evidence-based and documented. One of the most effective technique when collecting information for a job analysis is to obtain information through direct observation as well as from the most qualified incumbent(s) via questionnaires or interviews.

Evidence-Based Approach Competencies

- Consult the literature for solutions to HR challenges.

- Promote the use of data and quantitative and qualitative research in the decision-making process.

- Document the rationale for HR decisions.

Source: HRPA Professional Competency Framework (2014) , pg. 11. © HRPA, all rights reserved.

The following describes the most common job analysis methods.

Open-ended questionnaire

Job incumbents and/or managers fill out questionnaires about the Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities (KSA’s) necessary for the job. HR compiles the answers and publishes a composite statement of job requirements. This method produces reasonable job requirements with input from employees and managers and helps analyze many jobs with limited resources.

Structured questionnaire

These questionnaires only allow specific responses aimed at determining the nature of the tasks that are performed, their relative importance, frequencies, and, at times, the skills required to perform them. The structured questionnaire is helpful to define a job objectively, which also enables analysis with computer models. This questionnaire shows how an HR professional might gather data for a job analysis. These questionnaires can be completed on paper or online, many are available for free.

In a face-to-face interview, the interviewer obtains the necessary information from the employee about the KSAs needed to perform the job. The interviewer uses predetermined questions, with additional follow-up questions based on the employee’s response. This method works well for professional jobs.

Observation

Employees are directly observed performing job tasks, and observations are translated into the necessary KSAs for the job. Observation provides a realistic view of the job’s daily tasks and activities and works best for short-cycle production jobs.

Work diary or log

A work diary or log is a record maintained by the employee and includes the frequency and timing of tasks. The employee keeps logs over a period of days or weeks. HR analyzes the logs, identifies patterns and translates them into duties and responsibilities. This method provides an enormous amount of data, but much of it is difficult to interpret, may not be job-related and is difficult to keep up-to-date. See : Job Analysis: Time and Motion Study Form (Account Creation Required) .

Evaluate and Verify the Data

Once obtained, job analysis information needs to be validated and evidence-based.. This can be done with workers performing the job or with the immediate supervisor, for accuracy purposes. This corroboration of the data will ensure the information’s accuracy, and can also help the employees’ acceptance of the job analysis data.

Using the Data to Yield a Job Analysis Report

Once the job analysis has been completed, it is time to write the job description. These are technical documents that can be very detailed. For example, here is a job analysis report conducted in the US by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) within strategic initiatives focusing on four occupations with primary responsibilities for safety and risk data collection, analysis, and presentation: Operations Research Analyst, Engineer, Economist, and Mathematician. In a totally different category of work, here is another one describing the job of Amusement and Recreation Attendant .

Job Analysis is a great deal of work. Are there any situations where a company would not want to complete Job Analysis? Do you think that all companies should complete Job Analysis? Why? Why not?

Job Analysis: The Process that Defines Job Relatedness

In the chapter on discrimination, we emphasized the importance of the concept of job relatedness. Jobs contain many elements, some of which are essential to doing the job, and others that are ideal or preferable, but not essential. A job analysis will distinguish between essential and non-essential duties. The essential requirements must be determined objectively and employers should be able to show why a certain task is either essential or non-essential to a job.

Finding out the essential characteristics of a job is fundamental in determining whether some employment decisions are discriminatory or not. For example, a hiring requirement that states ‘frequent travel’ will disproportionately impact women with major caregiving responsibilities. When travel is included in a job description, it must be an essential duty otherwise its disparate impact on women will make it illegal. Moreover, even if travel is found to be an essential job duty, the employer would be expected to accommodate the family-status needs of employees. The purpose of a job analysis is to objectively establish the ‘job relatedness’ of employment procedures such as training, selection, compensation, and performance appraisal.

In order to comply with the law, an employer may consider the following questions:

- Is the job analysis current or does it need to be updated?

- Does the job analysis accurately reflect the needs and expectations of the employer?

- Which are essential requirements and which are non-essential?

“ 4.2 Job Analysis ” from Human Resources Management – 3rd Edition by Debra Patterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Human Resources Management Copyright © 2023 by Debra Patterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Missing Link of Job Analysis: A Case Study

- First Online: 23 April 2021

Cite this chapter

- Prerna Mathur 7 &

- Shikha Kapoor 7

Part of the book series: Asset Analytics ((ASAN))

505 Accesses

Any organization, in any industry, is able to perform efficiently when the objectives of the organization and the resulting objectives of the roles in the organization are unambiguous, structured, and well communicated and understood. In the event of lack of such clarity, the organization often faces various complex inter-related problems, such as wasted employee expertise, unrealistic performance standards, lack of human resource planning, incorrect talent hiring, talent gaps, low employee motivation, and so on. This case study, therefore, tries to elaborate upon the important link of job analysis that serves as a strong foundation in an organization to prevent many human-resource-related problems.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Compensation and Benefits: Job Evaluation

Bye-bye Job Descriptions

http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/job.html .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

AIBS, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Prerna Mathur & Shikha Kapoor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Prerna Mathur .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Amity Center for Interdisciplinary Research, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

P. K. Kapur

Group VC Amity International Business School, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Gurinder Singh

Department of Operational Research, University of Delhi, New Delhi, Delhi, India

Saurabh Panwar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Mathur, P., Kapoor, S. (2021). The Missing Link of Job Analysis: A Case Study. In: Kapur, P.K., Singh, G., Panwar, S. (eds) Advances in Interdisciplinary Research in Engineering and Business Management. Asset Analytics. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0037-1_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0037-1_11

Published : 23 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-0036-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-0037-1

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

BMI indicates body mass index; SES, socioeconomic status.

a Variables smoking status, SES, drinking pattern, former drinker bias only, occasional drinker bias, median age, and gender were removed.

b Variables race, diet, exercise, BMI, country, follow-up year, publication year, and unhealthy people exclusion were removed.

eAppendix. Methodology of Meta-analysis on All-Cause Mortality and Alcohol Consumption

eReferences

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Systematic Search Process for Studies of Alcohol Consumption and Risk of All-Cause Mortality

eTable 1. Newly Included 20 Studies (194 Risk Estimates) of All-Cause Mortality and Consumption in 2015 to 2022

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot of Log-Relative Risk (In(RR)) of All-Cause Mortality Due to Alcohol Consumption Against Inverse of Standard Error of In(RR)

eFigure 3. Relative Risk (95% CI) of All-Cause Mortality Due to Any Alcohol Consumption Without Any Adjustment for Characteristics of New Studies Published between 2015 and 2022

eFigure 4. Unadjusted, Partially Adjusted, and Fully Adjusted Relative Risk (RR) of All-Cause Mortality for Drinkers (vs Nondrinkers), 1980 to 2022

eTable 2. Statistical Analysis of Unadjusted Mean Relative Risk (RR) of All-Cause Mortality for Different Categories of Drinkers for Testing Publication Bias and Heterogeneity of RR Estimates From Included Studies

eTable 3. Mean Relative Risk (RR) Estimates of All-Cause Mortality Due to Alcohol Consumption up to 2022 for Subgroups (Cohorts Recruited 50 Years of Age or Younger and Followed up to 60 Years of Age)

Data Sharing Statement

- Errors in Figure and Supplement JAMA Network Open Correction May 9, 2023

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods