Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

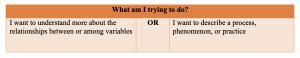

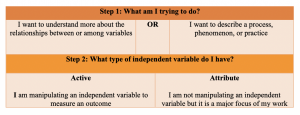

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

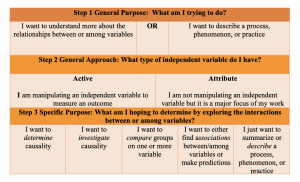

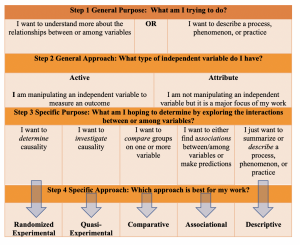

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

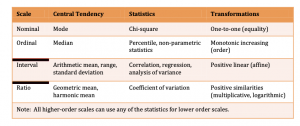

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

| Approach | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Thematic analysis | |

| Discourse analysis |

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Designing research projects

How to design better research projects, and how to develop your skill as someone who generates research projects.

Eleanor C Sayre

Designing good research studies is an important part of becoming a researcher, no matter what your field is. The exercises on this page are aimed at junior researchers who are designing their first studies in education research. If you’ve already done one or two projects, these exercises will help you get better at seeking funding and developing more projects. If you’ve never done research before, these exercises will help your first project be more successful.

If you are looking to design an education research project, the exercises on this page will help you. If you’re looking for advice on how to plan research projects is a good choice. You might also look at research process models to help you think about how research projects progress, or Iterative Design to think about to structure them for maximum likelihood of success.

If you’re doing video-based observational research, here’s a good companion piece to consider. If you’re thinking about Design-based research, check out this article .

More broadly, check out all articles tagged with “ doing research ”.

What does my project need?

Every project in education research needs to address four areas. While the details of these areas can be (should be) emergent, well-formed and successful research projects identify as much as possible ahead of time.

Every project needs:

| Area | Details |

|---|---|

| Research question | What do you want to study? |

| Access | What populations can you study, and how much time / which modalities are available? |

| Theory | What theoretical frameworks guide your work? |

| Methods | How will you generate observations and interpret them to become data? How many observations? |

Additionally, when you present your work for publication or funding, you will need to consider two more areas:

| Area | Details |

|---|---|

| Relevance | What intellectual merit or broader impacts will this project have? Why is this important or interesting work? |

| Audience | Where are you planning to publish your work? What counts as novel and important to them? |

We’re going to leave these two aside for now because they reference a broader sense of where the research community is, what societal needs are, and how your project fits into a much larger narrative. Those considerations are outside the scope of this guide, though you might consider reading ahead to other guides on writing. Let’s work on the four primary areas.

In a good research project, the four areas are all tightly related and supportive of each other. You should develop them in concert with each other. The exercises on this page will help you design a research study, and they will also help you develop your design skills in general.

Details of the four areas

Research questions.

Your research question(s) tie together your theoretical frameworks, methods, and access. They give purpose to your data collection and analysis. Answering them generates new knowledge about human behavior. In the ordinary process of doing research or thinking about the world, you will ask lots of questions. As you pursue some of them, you’ll develop follow-up questions and related lines of inquiry.

Research Question templates

If you’re in the very beginning stages of thinking about your project, you might need help brainstorming some possible research questions. Here are some templates to get you started. It’s not an exhaustive list.

- Theory X says A, but theory Y says B. How can they be made commensurate?

- This paper used population A, but I have population B. How can I apply their findings to my population?

- Surveys shows that students can do X. What is the actual process of learning to do X?

- What are the moderating factors which control success at task X?

- Our previous work shows X happens sometimes. Why does X occur?

- What’s better at teaching X, curriculum A or curriculum B?

- How do teachers make sense of X in light of Y?

Making your research question better

When you have an idea about what you’d like to investigate, you need to refine your ideas into a research question that suggests how you will answer it and how you will know when it is answered.

A good research question has the following properties:

- It is phrased a question, not a statement of problem

- Specific enough to be answerable

- Open to complicated, robust answers

- Interesting to investigate

You will want to have two versions of your research question: one that uses regular language, and a longer one (possibly with subquestions!) that uses specific, technical language.

This exercise helps you refine your ideas into a research question.

Write your question in the form of a question. Use regular language.

Make it specific. Your research question needs to be answerable in principle, and your research design needs to have a high likelihood of answering it.

- If your research question uses comparison language, what are you comparing? For example, if your research question is about whether a new curriculum is “better” or if students are learning “more”, what will you be comparing it to? Do you need to collect baseline data? Will you be able to run a treatment group and a control group at the same time?

- If your research question uses development language (e.g. “learning”), over what time are your subjects changing? An hour? Four years? Their lives? How will you know if change is durable? how will you know if it occurs at all?

Open it up to complicated, robust answers.

- If your research question has a binary answer (“does X happen?”), revise it to permit a more subtle answer (“to what extent does X happen?”; “how much does Y mediate X happening?”; “under what conditions can X be optimized to happen?”)

- If your research question is too specific (“what is the correlation coefficient of X with Y?”), you are too specific. Revise your question to have more robust answers (“how do X and Y relate?”; “what factors affect X and by how much?”)

Check: does answering this question sound like fun to you?

- If you refined your question so much that finding the answer sounds boring, trivial, or insurmountably hard, try new ways to refine it so that it really captures your interest in this topic.

In the process of refining your research question, you might realize that there are a bunch of interesting sub-questions to pursue. Go ahead and list them out, and follow this same process to refine them. Your refinements probably also include technical language and reserved words that mean something specific to the research project. Define each reserved word and link it to specific theoretical frameworks, methods, or data streams.

A good research question is a living question. As you interact with theories and data , it will necessarily change. The more specific you can make it in the beginning, the better you will be able to see it change and adjust your future work in an intentional way. You may find it useful to read Engle et al’s “ Progressive Refinement of Hypotheses in Video-Supported Research ” to understand how research questions can change and in response to repeated engagement with data, and Iterative Design to think about how to design for this feature.

The Access area is about practical constraints on your project: what populations do you have access to, and in which modalities? how much time do you have, and which analysis resources can you marshal? Of all the areas, Access is the one which is usually fixed earliest in the project, because the kinds and amounts of data you have access to are usually determined before you can collect any data at all, and the scope of your project is usually outside your control.

Questions that detail your access to data:

- What kinds of people will you measure? Some examples: introductory students, pre-service teachers, graduate teaching assistants, third graders in a specific elementary school.

- In what modalities can you collect data from them? Some examples: I can talk to them individually in interviews once per person, I can video them in class every day, I can put a problem on their final exam, I have three years of archival data but cannot collect new data, etc.

- How many people / how much data? One or two significant figures are ok here: about 10 students, about 300 students, about 20 hours of video, about 100 matched pre-post tests, etc

You probably can’t answer all of these questions alone. Get specific guidance from your collaborators, advisor, and people who control your access to research subjects (their instructors, their principals, the registrar, the data librarian, etc) – the members of your Advisory Board . At early design stages, you don’t need to seek IRB approval yet, and you don’t need written permission from every stakeholder. When your study is more fully designed , you will talk to these people again to firm up the details of your access and adjust your research questions and methods.

Questions that detail your access to resources:

- How long can you spend collecting data? How long analyzing it?

- How many researchers will be involved in data collection and analysis? What are their skill levels?

- How much data (and what kinds) can you reasonably expect to collect / analyze in the amount of time and effort that are available to you?

It is entirely possible that you have access to more data and analysis resources than you will need or use in your project. That’s great! You don’t need to collect (or use) everything. Alternately, you might not have enough access (or the right kind of access) to do the study you really want to do. That’s disappointing. You will need to adjust your research questions and methods in light of how much (and what kinds) of data you can collect or analyze with your resources.

On rare occasions, you can use your research questions to argue for access to more resources or different modalities. For example, suppose your research question is about student epistemology and persistence, and you already have access to students’ attitude survey scores. You might be able to ask the registrar for students’ demographics and final grades to enhance your analysis.

Theoretical frameworks

The role of your theoretical frameworks is to tell you why your observations are meaningful and in what ways your analyses generate new knowledge. Without a theoretical framework, your observations are meaningless and your work is unpublishable.

The primer on theory covers what you need theory for, an organizing framework for deciding which theory or theories to use, some theory options in education research, and some other common considerations.

The best theoretical frameworks are a) explicit; b) well-matched to your research question and methods; and c) intentionally chosen. There isn’t a “best framework” for everyone, or even every research question, and there are a lot of options available.

I’m using “Theoretical framework” in a loose sense to include things like knowledge-in-pieces , communities of practice, speech genres, models of institutional change, error-based learning, etc. (I’ve used all of these, and there are a lot more out there.) Some people use the phrase “theoretical-methodological framework” to acknowledge that good frameworks must tie theory, methods, and data together.

In this article, I’m not going to explore those subtleties.

Methodology

The role of your methodology is to tell you how to generate observations to answer your research question, how to convert those observations into data , and how to analyze that data. While theoretical frameworks are mostly concerned with why those observations and analyses are meaningful or interesting, methodologies are mostly concerned with the practicality of converting observations into analyses and the reasons for those analyses.

It is becoming a lot more common in discipline-based education research to be explicit about the methods that you choose and why. While it used to be sufficient in papers to outline what you did, now you also need to discuss why you did it and how it fits into a broader research tradition.

Many projects – especially large projects – coordinate multiple kinds of data and multiple kinds of analyses in order to make robust conclusions. This is (broadly) called “mixed-methods” or “multi-methods” design. There are lots of ways to mix methods well (and some ways to do it badly). If your research questions demand multi- or mixed-methods, you will need to write sub-research questions and choose theoretical frameworks for each method, and you will need to think about how the analyses from each method will interact to generate new knowledge. Before you jump into a mixed-methods design, ask yourself carefully if your research questions really warrant it, and if your access really allows it.

Sources for theoretical frameworks and methodologies:

There are books and papers written on this subject. Some of them are textbook-style for students; others are monograph style for researchers. To find them, you will have to step outside your particular discipline and look at the broader educational research literature, the learning sciences, or psychology (depending on your research questions).

- The Journal of the Learning Sciences has an excellent series on methodology and many beautiful papers on theory.

- Reviews in PER has a few papers with brief overviews of some kinds of methods and theories.

- Probably the most highly-cited book on methods is Creswell’s book on research design. It is not comprehensive, but it is extensive.

- There’s a quick overview of coding qualitative data (aimed at UX researchers) on Delve

- Shayan Doroudi wrote an excellent primer on learning theories.

- When you read papers , make note of their frameworks and methods (and their citations!).

You can also talk to other humans!

- Talk to your advisor or collaborators about what they would use (or require you to use).

- Write a one-page prospectus that outlines what you want to do and why you think it’s interesting or important, and send it to someone who does similar work. Ask them (nicely) for suggestions.

Develop the four areas in concert for a specific research project

In this exercise, you’re going to iteratively refine each of the four areas so that they are tightly integrated with each other.

On a whiteboard, write down a preliminary research question. If you don’t have a preliminary research question, start with one of the research question templates or do the exercise on making better research questions.

Write down what kind of access you have. Be specific about what populations, what kind of resources you have to undertake this research and how long it will take, and what kind of data modalities are available to you.

If you’re structurally constrained (by your funder, or your advisor, or your equipment) to use particular methods or theories, write them down as well.

Return to your research question, and update it so that it is constrained to the populations you have access to (as well as other structural constraints). It will get longer and more detailed. That’s great.

Which theories support your research question? Write them down. Amend your research question to explicitly reference at least one theoretical framework. If your question is about how individuals develop, you might look at the Resource Framework . If it’s about how communities form, try Communities of Practice. If you don’t know any theories, what have you read that makes you think this would be an interesting research question? You might need to use two or three frameworks in concert with each other to fully answer your research question.

What kind of data will you collect? Here’s a quick overview of the common kinds of data .

- Make sure that your access permits this kind of data, that your theoretical framework will be able to use the data from it, and that it will be able to answer your research question.

- Amend your research question and theoretical framework(s) to reflect the kind of observations you will collect. You might triangulate across several different data streams: preliminary surveys will identify participants for in depth interviews , and you ask them for their homework, for example.

How much data will you need to collect or analyze to show the effects you are looking for? Part of the answer to this question is about where you plan to publish your results at the end of your study: if you want to exhaustively prove your solution, you need a lot of evidence, but if you are only looking to prove its existence, you don’t need as much. Even a thoroughly theory-driven, theory-generating project needs something data-like (reinterpretation of old data, for example).

- If your project is based on finding patterns of human behavior, there are formalized methods for estimating effect sizes (generally known as a “power analysis” or “power estimate”). A quick-n-dirty estimate is that your error bars will go like 1/sqrt(N). If you can estimate differences in your treatments based on the literature, you can guess about how many subjects you will need. If your estimates suggest you will need many more subjects than you have access to, you need to revise your research question.

- If your project is based on finding cases of human behavior, you will need to think carefully about episode selection. How many episodes will you need to prove your point substantially? A good estimate is 3-5, most of which should be similar and one of which should be contrasting. More or fewer are possible.

Adjust your research question and methods in light of how much data you will be able to generate.

Write down a preliminary data collection and analysis plan.

- You may find that drawing a logic model or conjecture map is helpful. You may find that a narrative of what you’re planning to do and how is helpful.

- Compare your plan with your chosen theories and research question. Does your plan make use of your theories? Is it likely to answer your research question? Is it possible with the time and resources you have allotted?

Imagine that everything in data collection goes swimmingly and all of your data are fantastic. What does the answer to your research question look like? To what extent can you answer it with your methods and access? If course, you won’t know exactly what the answer will be – if you already knew, it wouldn’t be research – but you should be able to guess at an approximate shape to the answer.

- If you think you’ll need additional kinds of data to better triangulate an answer your question, amend your access and methods.

- If you think you’ll need a lot more data than you can get, amend your research question.

Another process which can help with intentional research design is conjecture mapping ; you might also consider the emergent processes outlined in “ Progressive Refinement… ”. If your research project is larger than you can complete in one semester, you are strongly encouraged to think about an iterative design using the principles in Planning Research Projects . Alternately, if your research project has a substantial curriculum development aspect, you should consider Design-Based Research (DBR). Lastly, you might consider whether your project is research at all: maybe you’re doing evaluation, not research .

Develop your skill in designing research projects

These exercises will develop your skill in designing research projects. If you do them a lot, then designing research studies will become a habit for you.

When you read papers , imagine using their theory and methods with a different population, or using their access with different theory and methods, or their research question with different access and methods. Make notes about your choices, so that later you can cite these papers in your own work. This exercise also makes you a better reader of papers.

Read through the abstracts of NSF’s recent awards for either IUSE or EDU:CORE . For every project, imagine that you have been given a supplement to do some research related to that project. What would be interesting? What would be possible, but not personally interesting? What would be exciting, but you don’t know very much about? You should be able to find something personally interesting or exciting in almost all of the projects. Design a study for each. This exercise also makes you a better citizen of the broader education research community, because you will know a lot more about the shape of current work in the community.

Read through the NSF’s upcoming deadlines for programs sponsored by Directorate for STEM Education (EDU), particularly the DUE and DRL divisions. For each one, sketch out a research study: what would you investigate? who might you partner with? This exercise also makes you a better researcher, because you will become more knowledgeable about how to frame your work to get funding.

Generative writing is the biggest tool in your researcher toolbox. Go back to your old notes about research designs, and enrich them with your new thoughts as you learn more.

Check out all articles in this Handbook tagged with “ doing research ”.

Read this delightful piece by the former editor of Sociology of Education.

Read this paper on quality in qualitative research design: Tracy, S.J., 2010. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative inquiry, 16(10), pp.837-851.

Read this paper on elements of research project designs.

Read this overview on designing projects for the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Additional topics to consider

Planning research projects.

How to develop a timeline for an education research project that makes space for emergence.

Evaluation and Research

What is the difference between evaluation and research?

Data and Access

What are the common kinds of data in education research, and what are their affordances and constraints?

This article was first written on January 1, 2015, and last modified on May 30, 2024.

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

14 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

This post is really helpful.

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

This post has been very useful to me. Confusing areas have been cleared

This is very helpful and very useful!

Wow! This post has an awful explanation. Appreciated.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Considerations in Designing Your Research Approach

Once you’ve identified your area of interest, sorted through and analyzed the literature to identify the problem you’d like to address, and developed both a purpose and a question; the next step is to design your study. This chapter will provide a basic overview of the considerations any researcher must think about as they design a research study.

Chapter 2: Learning Objectives

As you work to identify the best approach to identify an answer to your research question, you will be able to:

- Compare the conceptualization and operational activities of the process

- Discuss the difference between an independent and dependent variable

- Discuss the importance of sampling

- Contrast research approaches

- Demonstrate a systematic approach to selecting a research design

Understanding the Language of Research

As you work to determine which approach you will consider in order to best answer your question, you’ll need to consider how to address both the conceptual and operational components of your inquiry. As we discussed in Chapter 1; theory often informs practice (deductive approaches). Theory is often discussed in terms of abstract, or immeasurable, constructs. Because of the ambiguous nature of theory, it is important to conceptualize the parameters of your investigation. Conceptualizing is the process of defining what is or is not included in your description of a specific construct.

Understanding Theoretical and Contextual Framework

You may consider the theoretical or contextual framework for your study as the ‘lens’ through which you want your reader to view the work from. That is, this is your opportunity frame their experience with this information through your educated perspective on the material.

How Will You Determine the Subjective Aspects of Your Work?

Consider exploring one’s motivation to advance their education:

- That is if you’re determining whether clinicians who have advanced credentials are more motivated at work; you’ll need to create a clear delineation between motivation and effort and work out how to measure each of these independently

Operationalization is the process of defining concepts or constructs in a measurable way. As you dive into the ‘HOW’ you will go about your research, you will need to understand the terminology related to study design

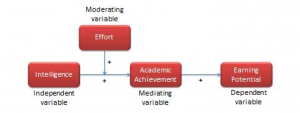

As we discussed in Chapter 1, there are several kinds of Variables. As a reminder, a variable is an objective and measurable representation of a theoretical construct. An independent variable is a variable which causes an effect on the dependent, or outcome variable. Note that there may be more than one independent variable in your study. Therefore, the dependent variable is the variable which you are measuring as an effect of an intervention or influence; you can think of this as the outcome variable. Identifying at least these two variables is an essential first step in designing your study. This is because how you explore the relationship between your effect (independent variable) and outcome (dependent variable) with help guide your methodology. Other variables to consider include mediating variables , which are variables that are explained by both the independent and dependent variables. Moderating variables influence the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and control variables which may have an impact on the dependent variable but does not help to explain the dependent variable.

Assigning Dependent and Independent Variables

You would like to determine the relationship between weight and tidal volume:

- Dependent Variable : Which variable DEPENDS on the other? Or, which variable will define the OUTCOME? ( Tidal volume)

- Independent Variable : Does the variable INFLUENCE, HELP EXPLAIN, or have an IMPACT on the dependent variable? (Weight)

You would like to determine whether the number of hours spent in clinical training influences post training test scores :

- Dependent Variable : Score on post training test

- Independent Variable : Number of hours in clinical training

Identifying and assigning the dependent and independent variable(s) is one of the most important research activities as this will help guide you toward the type of information you’ll be collecting and what you will do with that information. However, as you consider both the outcome (dependent) variable and the impact (independent) variable, it is also important to consider what other variables may influence the relationship between these two primary variables.

There are very few instances wherein you can control EVERY variable. However, it is your job as a researcher to plan for, acknowledge, and attempt to address anything that may influence the results you present.

levels of measurement can be thought of as values within each variable. For example, traditionally, the variable ‘Gender’ had two values: male or female. The modern variable of ‘Gender’ may have several values which are used to delineate each potential designation within the variable. Each value represents a specific designation of measure.

Values of measures may be considered quantitative (numeric); in our example of traditional gender you may assign a numeric (quantitative) value to male and female as either ‘1’ and ‘2’, respectively. Values may also be assigned non-numerically; meaning they are qualitative. It is important to note that if you want to analyze non-numeric data, it must be coded first.

Understanding and Assigning Value

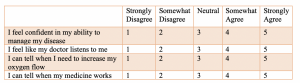

You may create a question asking respondents to rank their agreement with a statement on a scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Although qualitative in nature, we can assign a numeric value to each level of measurement as a ‘code’.

- 1= Strongly Disagree

- 2= Somewhat Disagree

- 3= Neither Disagree nor Agree

- 4= Somewhat Agree

- 5= Strongly Agree

By doing this, we can explore relationships between the attributes and variables using quantitative statistical methods.

Levels of measurement

One of the most important aspects of operationalizing a theoretical construct is to determine the level(s) of measurement. This is done by assessing the types of variables and values:

- Nominal : also called categorical. This level of measurement is used to describe a variable with two or more values BUT there is no intrinsic ordering to the categories

Example of a Nominal Variable

You would like to collect information about the gender (variable) of individuals participating in your study. Your level of measures may be:

You may then assign these measures a numeric value:

- Non-Binary=3

- Ordinal : This level of measurement is used to describe variable values that have a specific rank order. BUT that order does not indicate a specificity between ranks.

Example of an Ordinal Variable

You provide a scale of agreement for respondents to indicate their level of agreement with the use of a current policy within the hospital:

- Strongly Agree

- Strongly Disagree

Note: Those who strongly disagree with the use of this policy disapprove MORE than do those who disagree; however, there is no quantifiable value for how much more.

- Interval : You’ll use this level of measurement for variable values which are rank ordered AND have specified intervals between ranks and can tell you ‘how much more’.

Example of an Interval Variable

You classify the ages of the participants in your study:

- 18-24 years old

- 25-30 years old

- 31-35 years old

- >35 years old

NOTE: 35 is 5 more than 30. The quantifiable ‘how much more’ is what distinguishes age as an interval variable.

- Ratio : Ratio values have all of the qualities of a nominal, ordinal, and/or interval scale BUT ALSO have a ‘true zero’. In this case true zero indicates a lack of the underlying construct (i.e. it does not exist). Additionally, there is a ratio between points on this particular scale. That is, in this case, 10 IS twice that of 5.

Example of a Ratio Variable

You are doing a pre and post bronchodilator treatment trial for a new drug. You must establish baseline heart rate in your treatment group:

- Pulse rate is a ratio variable because the scale has an absolute zero (asystole) and there is a ratio between the number of times the heart beats (i.e. a change in heart rate of 10 beats per minute)

Identification of variable and values is essential to a successful project. Not only will doing this early in the process allow you to predict factors that may affect your research question, but it will also guide you toward the type of data you will collect and determine what kind of statistical analyses you will likely be performing in order to understand and present the results of your work.

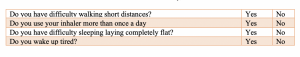

Scales are used to glean insight into a situation or phenomenon and can be used to help quantify information that would otherwise be difficult to understand or convey. Although there are several types of scales used by researchers, we’ll focus on the two of the most common:

- Binary scale : Nominal scale that offers two possible outcomes, or values. Questions that force a respondent to answer either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ utilize a binary scale. IF you offer more than two options, your scale is no longer binary, but is still a nominal scaled item

- Likert scales : Likert scales are popular for measuring ordinal data and include indications from respondents. Data can be quantified using codes assigned to responses and an overall summation for each attribute can be associated with each respondent

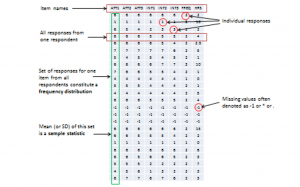

Sampling is the statistical process of selecting a subset (called a “sample”) of a population of interest for purposes of making observations and statistical inferences about that population. We cannot study entire populations because of feasibility and cost constraints, and hence, we must select a representative sample from the population of interest for observation and analysis. It is extremely important to choose a sample that is truly representative of the population so that the inferences derived from the sample can be generalized back to the population of interest. Probability sampling is a technique in which every unit in the population has a chance (non-zero probability) of being selected in the sample, and this chance can be accurately determined. An example of probability sampling is simple random sampling wherein you include ALL possible participants in a population and utilize a method to randomly select a sample that is representative of that population. Nonprobability Sampling is a sampling technique in which some units of the population have zero chance of selection or where the probability of selection cannot be accurately determined. Typically, units are selected based on certain non-random criteria, such as quota or convenience. Because selection is non-random, nonprobability sampling does not allow the estimation of sampling errors, and may be subjected to a sampling bias. Therefore, information from a sample cannot be generalized back to the population. An example of nonprobability sampling is utilizing a convenience sample of participants due to your close proximity or access to them.

Why does sampling matter?

When you measure a certain observation from a given unit, such as a person’s response to a Likert-scaled item, that observation is called a response. In other words, a response is a measurement value provided by a sampled unit. Each respondent will give you different responses to different items in an instrument. Responses from different respondents to the same item or observation can be graphed into a frequency distribution based on their frequency of occurrences. For a large number of responses in a sample, this frequency distribution tends to resemble a bell-shaped curve called a normal distribution, which can be used to estimate overall characteristics of the entire sample, such as sample mean (average of all observations in a sample) or standard deviation (variability or spread of observations in a sample). These sample estimates are called sample statistics (a “statistic” is a value that is estimated from observed data). Populations also have means and standard deviations that could be obtained if we could sample the entire population. However, since the entire population can never be sampled, population characteristics are always unknown, and are called population parameters (and not “statistic” because they are not statistically estimated from data). Sample statistics may differ from population parameters if the sample is not perfectly representative of the population; the difference between the two is called sampling error. Theoretically, if we could gradually increase the sample size so that the sample approaches closer and closer to the population, then sampling error will decrease and a sample statistic will increasingly approximate the corresponding population parameter.

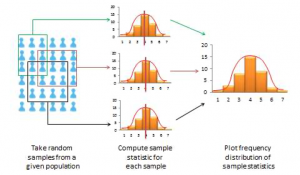

If a sample is truly representative of the population, then the estimated sample statistics should be identical to corresponding theoretical population parameters. How do we know if the sample statistics are at least reasonably close to the population parameters? Here, we need to understand the concept of a sampling distribution . Imagine that you took three different random samples from a given population, as shown below, and for each sample, you derived sample statistics such as sample mean and standard deviation. If each random sample was truly representative of the population, then your three sample means from the three random samples will be identical (and equal to the population parameter), and the variability in sample means will be zero. But this is extremely unlikely, given that each random sample will likely constitute a different subset of the population, and hence, their means may be slightly different from each other. However, you can take these three sample means and plot a frequency histogram of sample means. If the number of such samples increases from three to 10 to 100, the frequency histogram becomes a sampling distribution. Hence, a sampling distribution is a frequency distribution of a sample statistic (like sample mean) from a set of samples, while the commonly referenced frequency distribution is the distribution of a response (observation) from a single sample. Just like a frequency distribution, the sampling distribution will also tend to have more sample statistics clustered around the mean (which presumably is an estimate of a population parameter), with fewer values scattered around the mean. With an infinitely large number of samples, this distribution will approach a normal distribution. The variability or spread of a sample statistic in a sampling distribution (i.e., the standard deviation of a sampling statistic) is called its standard error. In contrast, the term standard deviation is reserved for variability of an observed response from a single sample.

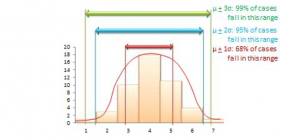

The mean value of a sample statistic in a sampling distribution is presumed to be an estimate of the unknown population parameter. Based on the spread of this sampling distribution (i.e., based on standard error), it is also possible to estimate confidence intervals for that prediction population parameter. Confidence interval is the estimated probability that a population parameter lies within a specific interval of sample statistic values. All normal distributions tend to follow a 68-95-99 percent rule (see below), which says that over 68% of the cases in the distribution lie within one standard deviation of the mean value (μ 1σ), over 95% of the cases in the distribution lie within two standard deviations of the mean (μ 2σ), and over 99% of the cases in the distribution lie within three standard deviations of the mean value (μ 3σ). Since a sampling distribution with an infinite number of samples will approach a normal distribution, the same 68-95-99 rule applies, and it can be said that:

- (Sample statistic one standard error) represents a 68% confidence interval for the population parameter.

- (Sample statistic two standard errors) represents a 95% confidence interval for the population parameter.

- (Sample statistic three standard errors) represents a 99% confidence interval for the population parameter.

A sample is “biased” (i.e., not representative of the population) if its sampling distribution cannot be estimated or if the sampling distribution violates the 68-95-99 percent rule. As an aside, note that in most regression analysis where we examine the significance of regression coefficients with p<0.05, we are attempting to see if the sampling statistic (regression coefficient) predicts the corresponding population parameter (true effect size) with a 95% confidence interval. Interestingly, the “six sigma” standard attempts to identify manufacturing defects outside the 99% confidence interval or six standard deviations (standard deviation is represented using the Greek letter sigma), representing significance testing at p<0.01.

Types of Research Designs

There are many different approaches to research. The list provided here is not exhaustive by any means; rather, this is a brief list of the most common approaches you may identify as you review the literature related to your interest.

Experimental

Experimental research is typically performed in a controlled environment so that the researcher can manipulate an independent variable and measure the outcome (dependent variable) between a group of subjects who received the manipulated variable (intervention) and a group of subjects who did not receive the intervention. This type of design typically adheres to the scientific method in order to test a hypothesis. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon and serves as the starting point for the investigation. You may see a hypothesis indicated as (H O ), also called the null hypothesis. This is to differentiate it from an alternative hypothesis (H 1 or H A ), which is any hypothesis other than the null.

Development of the Hypothesis

There are two types of hypotheses, the null (HO) and an alternative (H 1 or H A )