Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Homework copying can turn As into Cs, Bs into Ds

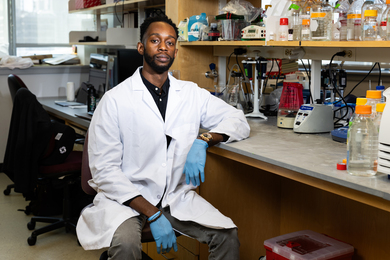

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Physical Review Special Topics: Physics Education Research paper

- David E. Pritchard

- Young-Jin Lee

Related Topics

- Education, teaching, academics

More MIT News

Study: Transparency is often lacking in datasets used to train large language models

Read full story →

How MIT’s online resources provide a “highly motivating, even transformative experience”

Students learn theater design through the power of play

A framework for solving parabolic partial differential equations

Designing better delivery for medical therapies

Making a measurable economic impact

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

The push against homework is not just about the hours spent on completing assignments; it’s about rethinking the role of education in fostering the well-rounded development of young individuals. Critics argue that homework, particularly in excessive amounts, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout, and a diminished love for learning. Moreover, it often disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating educational inequities. The debate also highlights the importance of allowing children to have enough free time for play, exploration, and family interaction, which are crucial for their social and emotional development.

Checking 13yo’s math homework & I have just one question. I can catch mistakes & help her correct. But what do kids do when their parent isn’t an Algebra teacher? Answer: They get frustrated. Quit. Get a bad grade. Think they aren’t good at math. How is homework fair??? — Jay Wamsted (@JayWamsted) March 24, 2022

As we delve into this discussion, we explore various facets of why reducing or even eliminating homework could be beneficial. We consider the research, weigh the pros and cons, and examine alternative approaches to traditional homework that can enhance learning without overburdening students.

Once you’ve finished this article, you’ll know:

Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts: Diverse Perspectives on Homework

Here are the insights and opinions from various experts in the educational field on this topic:

“I teach 1st grade. I had parents ask for homework. I explained that I don’t give homework. Home time is family time. Time to play, cook, explore and spend time together. I do send books home, but there is no requirement or checklist for reading them. Read them, enjoy them, and return them when your child is ready for more. I explained that as a parent myself, I know they are busy—and what a waste of energy it is to sit and force their kids to do work at home—when they could use that time to form relationships and build a loving home. Something kids need more than a few math problems a week.” — Colleen S. , 1st grade teacher

“The lasting educational value of homework at that age is not proven. A kid says the times tables [at school] because he studied the times tables last night. But over a long period of time, a kid who is drilled on the times tables at school, rather than as homework, will also memorize their times tables. We are worried about young children and their social emotional learning. And that has to do with physical activity, it has to do with playing with peers, it has to do with family time. All of those are very important and can be removed by too much homework.” — David Bloomfield , education professor at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York graduate center

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’” — John Hattie , professor

”Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll – psychologically and in many other ways too. We see kids getting up hours before school starts just to get their homework done from the night before… While homework may give kids one more responsibility, it ignores the fact that kids do not need to grow up and become adults at ages 10 or 12. With schools cutting recess time or eliminating playgrounds, kids absorb every single stress there is, only on an even higher level. Their brains and bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.” — Pat Wayman, teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com

7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Let’s delve into the reasons against assigning homework to students. Examining these arguments offers important perspectives on the wider educational and developmental consequences of homework practices.

1. Elevated Stress and Health Consequences

This data paints a concerning picture. Students, already navigating a world filled with various stressors, find themselves further burdened by homework demands. The direct correlation between excessive homework and health issues indicates a need for reevaluation. The goal should be to ensure that homework if assigned, adds value to students’ learning experiences without compromising their health and well-being.

2. Inequitable Impact and Socioeconomic Disparities

Moreover, the approach to homework varies significantly across different types of schools. While some rigorous private and preparatory schools in both marginalized and affluent communities assign extreme levels of homework, many progressive schools focusing on holistic learning and self-actualization opt for no homework, yet achieve similar levels of college and career success. This contrast raises questions about the efficacy and necessity of heavy homework loads in achieving educational outcomes.

3. Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

The issue is not confined to specific demographics but is a widespread concern. Samantha Hulsman, a teacher featured in Education Week Teacher , shared her personal experience with the toll that homework can take on family time. She observed that a seemingly simple 30-minute assignment could escalate into a three-hour ordeal, causing stress and strife between parents and children. Hulsman’s insights challenge the traditional mindset about homework, highlighting a shift towards the need for skills such as collaboration and problem-solving over rote memorization of facts.

4. Consumption of Free Time

Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish , in their book “The Case Against Homework,” offer an insightful window into the lives of families grappling with the demands of excessive homework. They share stories from numerous interviews conducted in the mid-2000s, highlighting the universal struggle faced by families across different demographics. A poignant account from a parent in Menlo Park, California, describes nightly sessions extending until 11 p.m., filled with stress and frustration, leading to a soured attitude towards school in both the child and the parent. This narrative is not isolated, as about one-third of the families interviewed expressed feeling crushed by the overwhelming workload.

5. Challenges for Students with Learning Disabilities

In conclusion, the conventional homework paradigm needs reevaluation, particularly concerning students with learning disabilities. By understanding and addressing their unique challenges, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. This approach not only aids in their academic growth but also nurtures their confidence and overall development, ensuring that they receive an equitable and empathetic educational experience.

6. Critique of Underlying Assumptions about Learning

7. issues with homework enforcement, reliability, and temptation to cheat, addressing opposing views on homework practices, 1. improvement of academic performance, 2. reinforcement of learning, 3. development of time management skills, 4. preparation for future academic challenges, 5. parental involvement in education, exploring alternatives to homework and finding a middle ground, alternatives to traditional homework, ideas for minimizing homework, useful resources, leave a comment cancel reply.

- August 25 BTSD kicks off new school year on right note

- August 25 The foundation of democracy: Voting education in school

- July 12 Utopia or Dystopia? The hidden history of Bay Area cults

- June 29 Public protests and perspectives

- June 27 Reflejando otra vez con los ELD seniors

- June 27 A letter to sophomores: how to run next year’s marathon

- June 22 What it means to be a Giant

- June 21 Senior Maze

- June 21 Spring Sports Recap

- June 20 The bulging red bumps of your teen years should not be normalized: Acne vulgaris, a detrimentally neglected disease

- June 15 Redwood class of 2024 graduates amid tears, cheers and airhorns: A celebration to remember

- June 13 El fútbol en España: un pilar cultural

Redwood Bark

- Top Culture

Epidemic of copying homework catalyzed by technology

What is it that leads students to neglect their own thoughts and brainlessly transcribe someone else’s for a passing grade? Similar to the bubonic plague, smallpox and Ebola, copying homework is the next epidemic, and it’s already here.

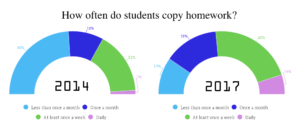

The March Bark survey found that 80 percent of Redwood students copy homework at least once a month. In 2014, a similar Bark survey found that only 53 percent of students were copying with that frequency.

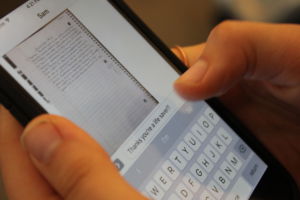

Increased technology use has contributed to the simplification of copying homework. In 2015, 64 percent of American adults owned a smartphone and the number for minors was hypothesized to be even more, according to the Pew Research Center. Another study in January found that now nearly 77 percent of American adults own a smartphone, presumably with an increased number for teenagers.

The recent Bark survey found that nearly five times the amount of students copy homework daily than three years ago in a 2014 Bark survey of similar caliber.

Sophomore “Erica” who wished to remain anonymous, admitted to copying homework a few times per week and addressed the prevalence of copying homework. Though Erica copies homework, she has been able to maintain passing grades in all of her classes, causing her to question the value of homework in the first place.

“Sometimes I don’t know how to do [homework], sometimes I don’t want to do it, sometimes I don’t have time to do it,” Erica said. “My answers aren’t always correct so if other people’s are, that’s better for the tests.”

Erica, along with 13 percent of students, according to a March self-representative Bark survey, admit to receiving homework a few times a week. Erica mostly copies homework via texting.

Chemistry teacher Marissa Peck recognized that copying homework was more difficult without the use of technology.

“[Copying was not as frequent when I was in school] mostly because we didn’t have phones that took pictures,” Peck said. “The main change I’ve seen over the last few years is that students take a picture of [homework] on their phone. I see students with someone else’s assignment pulled up on their phone and they’re just wholesale copying off of it, and that’s very frustrating.”

Guidance counselor Candace Gulden attributed the increase of students who copy homework to the intense academic culture at Redwood.

“I think students [copy homework] because they’re overwhelmed. One thing that I wish students would do is recognize that homework is there for you to practice and learn, you’re not really gaining anything by copying someone’s homework. You haven’t learned anything, you haven’t gained any skills,” Gulden said.

Peck stated that copying does not serve the ultimate purpose of homework: to learn and understand the classwork.

“I definitely have seen [copying]. I myself found that you don’t learn it as well, and it’s harder down the road,” Peck said. “I’m not assigning homework so they have more to do. It’s to reach the goal of learning something . ”

Peck grades a few assignments for each unit of Chemistry based on accuracy, which could arguably increase pressure on students to complete assignments correctly. However, she believes it allows her to see where students are, and for students to self-evaluate.

“I make that decision to check in and see how students are doing, to give students more feedback from me so that they can understand better where they’re making mistakes, and to know if I need to teach something. Teachers need to get feedback too, if I need to focus on one area. It’s for the students, but it’s also good information for me,” Peck said.

According to the Tamalpais Union High School District Parent/Student Handbook, repercussions for copying work can be severe. The handbook states that cheating can be grounds for suspension and even expulsion. Despite these dangers, 10 percent of students self-reported in the March Bark survey to copying homework daily. In 2014, only 2 percent of students did so in a Bark survey.

As a teenager’s prefrontal cortex and brain continue to develop, decision making is often impaired and taking risks is more appealing as it produces more of an adrenaline rush. Copying homework doesn’t exactly get your heart pumping, but students are still widely unaware of the consequences that come with copying homework, especially when their main focus is getting a passing grade. Because it is such a common occurrence, cheating doesn’t have any negative connotations

Erica stated that sometimes she even copies homework in class. Teachers like Peck use a variety of ways to minimize cheating during classes and especially on tests. Peck makes four different versions of tests to assure that students at the same table are not tempted to glance at another paper. In the future, she hopes to even add variety to homework assignments and incorporate more open ended questions which are more difficult to replicate from another student.

While the consequences can be extreme, some students use copying homework as a way to understand material with more clarity, since they can model their homework from the correct answers. Erica said she is more likely to do homework if there is an answer key accessible for her.

“Sometimes I don’t know how to do [the homework], but if someone else shows me, I can figure it out from their

answers,” Erica said.

Erica began copying homework in the early years of middle school. This year, she has began asking for homework from her peers more often with a busier schedule and harder classes. Not all of Erica’s classes correct homework before testing, and she believes that seeing other student’s work can be a good tool for studying and checking her own knowledge.

Forgetting your moral compass and succumbing to the rampant cheating has become a routine high school experience.

“Sometimes students don’t view it as cheating. When they’re looking at their friend’s assignment, or taking a picture of the answer key, those things really are cheating. Sometimes students don’t view, ‘ oh I’m giving my paper to my friend ’ as they are cheating too… There’s a little misunderstanding about what cheating is,” Peck said.

Gulden continues to reinforce her ideas to minimize cheating at Redwood, including helping students find their limits before they are pushed too far.

“I wish that students could see that big picture,” Gulden said. “I wish students would take a less rigorous schedule so they could focus more on learning each subject.”

However, despite the clear immorality of copying homework, one must wonder why they resort to this.

Many staff members recognize the intensity of Redwood’s cutthroat academic culture. However, faculty still have to teach a full curriculum and with students all taking various classes, it is difficult to optimize the homework load so that it is balanced for all students.

“I think there’s a combination of things going on. I think students specifically here have a lot on their plates. I do understand that when [students] get home they have sports, or drama commitments, or music commitments, or jobs. They have a lot of things they need to do and obligations,” Peck said. “Sometimes [cheating] is easier to do, and students need to do it.”

Gulden said despite hearing about cases of copying homework, it generally does not affect her written college recommendations, unless she encounters a repeat offender. Even then, Gulden generally works with students to get to the bottom of their issues.

“A lot of what we’re learning in school is to be able to function as an adult. I can’t just cheat off my colleagues or copy their assignments, you have to learn to be able to do these things on your own,” Gulden said.

Ultimately, students all develop unique paths through adolescence. Developing a habit of cheating creates a lack in work ethic and persistence that can halt student’s futures.

However, copying homework is a daunting issue to fix. In the last three years, the percentage of students copying homework has increased significantly, and the advances in technology will continue allowing for easy, accessible sharing. Copying homework may be immoral, but the workload students face and lack of work ethic will be the influencing factor on this generation’s leaders.

- copying homework

Academic Integrity at MIT

A handbook for students, search form, copying and other forms of cheating.

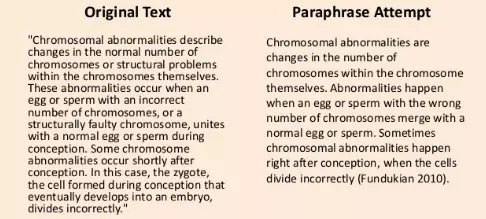

While guidelines on the acceptable level collaboration vary from class to class, all MIT instructors agree on one principle: copying from other students, from old course “bibles,” or from solutions on OCW sites is considered cheating and is never permitted .

Collaboration works for you; copying works against you.

If you copy, you are less prepared.

MIT Professor David E. Pritchard, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics, has said,“Doing the work trumps native ability.” Those who invest the time working through the problem sets are better prepared to answer exam questions that call for conceptual thinking.

If you copy, you aren’t learning.

Research done in 2010 by Professor Pritchard and others showed that those who copied more than 30% of the answers on problem sets were more than three times as likely to fail the subject than those who did not copy.

(Source: Pritchard, D.E. What are students learning and from what activity? Plenary speech presented at Fifth Conference of Learning International Networks Consortium 2010. Retrieved in July 2019 from http://linc.mit.edu/linc2010/proceedings/plenary-Pritchard.pdf )

If you copy, you violate the principles of academic integrity.

Copying is cheating. When you fail to uphold the principles of academic integrity, you compromise yourself and the Institute.

If you collaborate, you learn from your peers.

Every student brings a unique perspective, experience, and level of knowledge to a collaborative effort. Through discussion and joint problem solving, you are exposed to new approaches and new perspectives that contribute to your learning.

If you collaborate, you learn to work on a team

Gaining the skills to be an effective team member is fundamental to your success as a student, researcher and professional. As you collaborate with your peers, you will face the challenges and rewards of the collegial process.

Beyond Copying

Whether because of high demands on your time or uncertainty about your academic capabilities, you may be tempted to cheat in your academic work. While copying is the most prevalent form of cheating, dishonest behavior includes, but is not limited to, the following:

Changing the answers on an exam for re-grade.

Misrepresenting a family or personal situation to get an extension.

Using prohibited resources during a test or other academic work.

Forging a faculty member’s signature on a permission form or add/drop form.

Falsifying data or claiming to have done research you did not do.

Claiming work of others as your own by deliberately not citing them.

Assisting another student in doing any of the above.

(Adapted from: Jordan, David K. (1996). “Academic Integrity and Cheating.” Retrieved from http://weber.ucsd.edu/~dkjordan/resources/cheat.html in July 2019.)

If you are tempted to cheat, think twice. Do not use the excuse that “everybody does it.” Think through the consequences for yourself and others. Those who cheat diminish themselves and the Institute. Cheating can also negatively impact other students who do their work honestly.

If you observe another student cheating, you are encouraged to report this to your instructor or supervisor, the Office of Student Conduct and Community Standards , or reach out to the Ombuds Office for advice.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- School Stuff

- Surviving School

How to Deal With Classmates Who Want Answers to Homework

Last Updated: June 9, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a Private Tutor and Life Coach in Santa Cruz, California. In 2018, she founded Mindful & Well, a natural healing and wellness coaching service. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. Emily also received her Wellness Coach Certificate from Cornell University and completed the Mindfulness Training by Mindful Schools. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 123,201 times.

If you're a responsible and hardworking student, then it's likely your peers have asked for your homework answers. You may be tempted to break the rules and share your answers because of social pressure, but this hurts both you and the person who copies you. Protecting your answers from would-be cheaters is the right thing to do, and actually helps them become better students in the long run. You can prepare to resist peer pressure and avoid cheating by learning ways that you can say "no" to other students, as well as how to manage their expectations of you. Finally, consider starting a study group that allows you and your peers to learn together. It'll all be more productive for you and your friends.

- You may accidentally encourage your classmate to apply more pressure if you soften your “no” in an attempt to be friendly. Avoid using statements like “I don’t know” or “this may be a bad idea.” Instead, trust the clarity and power of a direct “no.”

- Do not provide a complicated answer, just say no. A complicated explanation that emphasizes unusual circumstances may seem friendlier or more helpful, but it can provide an opportunity for your classmate to challenge your refusal and to ask again.

- You can say “I know this is important, but my answer is not going to change,” or “I know that you are worried about grades, but I never share my answers.”

- If you feel yourself weakening, remind yourself of the consequences you could face if you're caught sharing answers. Your teacher could deny you credit for the work you've done since by sharing your work you've engaged in cheating.

- Remember that the long term repercussions outweigh the immediate pressure. A school year can seem like a very long time, and you may worry about awkward situations if you disappoint a classmate. If you say no to a classmate, you may feel uncomfortable for a few days or weeks. If you are caught cheating, the consequences can last for years.

- Point out to the student that the consequences remain even if you don't get caught. Copying homework answers doesn't help you learn the information, so the student who copies you won't be prepared for bigger assignments, such as the upcoming test. Even if they don't get caught now, they may not pass the course if they fail the test.

- Pay careful attention to your school’s rules regarding plagiarism. Plagiarism can seriously damage your academic record. Since what counts as plagiarism may not always be instinctive, speak with your teacher to clarify confusions that you may have. Your teacher will appreciate the opportunity address these questions before potentially plagiarized work is submitted.

- Remember, if the other student doesn't do the homework, then they aren't learning the course material. Most likely, they will fail the big assignments, such as tests.

- Keep in mind that sharing answers would make you guilty of cheating, as well. You could jeopardize your future if you decide to share your answers.

Managing Your Classmates’ Expectations

- When discussing your progress, highlight the effort you're putting into the class, but acknowledge that you won't know how well you know the subject until after your work is graded. Say, "I'm taking good notes and reading the material, but I won't know if my answers are right until I get my paper graded."

- Keep your homework concealed until the moment it is due. Discourage your classmates from asking for your homework answers by not publicizing it. If someone asks you for answers to homework that isn't due for quite a while, you can always lie that you haven't finished it yet.

- Anticipate cheating around test times. Due to the high value placed on providing specific answers for assigning grades, stress can increase before major tests. This may make cheating seem more attractive. Before a test or major assignment, encourage a student that may ask you for answers or offer to study with them. This may reinforce proper study habits and discourage cheating.

Creating a Study Group

- Ask your classmate about their study habits. You may be able to explain how they can do homework more effectively.

- Pay special attention not to emphasize the depth of your understanding. Your goal is to work with the student, not to give them answers. Make sure that they are actively involved.

Community Q&A

- Ask the teacher for advice in confidence. Most high school and college teachers understand the complex nature of social structures in their classrooms. If you are dissatisfied, consult another teacher in the department, your adviser or your dean (principal). Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 2

- Offer to help struggling classmates. You will learn as much as you teach, and you will lessen the need for and appeal of cheating. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 4

- Being an accomplice to cheating is usually punished as harshly as cheating. If you feel that your study group may be close to being a cheating ring, immediately seek consultation from a trusted adult. Thanks Helpful 16 Not Helpful 1

- Be sure that the teacher knows about your study group. Otherwise, when a few students miss the same questions on an assignment, the teacher will assume cheating has taken place. Thanks Helpful 5 Not Helpful 1

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/lib/learning-to-say-no

- ↑ https://www.educationworld.com/a_admin/admin/admin375.shtml

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evolution-the-self/201401/praise-manipulation-6-reasons-question-compliments

- ↑ http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ720382

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/education/2009/jun/09/how-to-be-a-student-study-group

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Daniel Brown

Jul 17, 2022

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How to deal with students copying?

In university courses with compulsory homework, I quite often find students copying their work from others. Now, you can simply ignore this since they are responsible for their learning. If not, usually a very annoying game starts, where students try to slightly modify their soultions and teachers become detectives. I am not sure if this is helpful.

Is there any literature or best practice experience on the problem of how to deal with copying of mathematics students?

- undergraduate-education

- 4 $\begingroup$ There is maybe a case where the game does not start: If you have homework where students have to write some code (e.g., in numerics this is often the case that some algorithm have to be implemented), then you can use plagiarism software (e.g. theory.stanford.edu/~aiken/moss ). The software analysizes the structure and ignores empty lines or renaming of variables. If a student can trick the software, he has almost done the same work as someone actually doing the exercise. However, your question have to be difficult and long enough. $\endgroup$ – Markus Klein Commented Mar 18, 2014 at 7:43

- 5 $\begingroup$ No literature, just personal anecdote: I had to grade homework questions where in the end only a certain threshold needed to be met (no marks, just pass/fail). My mode of grading work where the one student copied another one was awarding half the points with the remark "Same answers as XXX. Half the work, half the points." To my judgement, the message was recieved. For written homework (not code), I think that, if the students manage to obfuscade the fact that they copied, they put in some effort to understand what's to be done. $\endgroup$ – Roland Commented Mar 18, 2014 at 11:04

- 2 $\begingroup$ @Roland, I used to grade like that. In addition, I would also give the one who was copied from half the points. In effect, there was only one work, and two people claimed it, so half the points go to each. $\endgroup$ – JRN Commented Mar 18, 2014 at 13:47

- 2 $\begingroup$ @JoelReyesNoche Oh, yes, indeed. My notion of copying is transitive. Both parties with the same answer are getting half the points; I remember awarding one third of the points on three different homeworks. $\endgroup$ – Roland Commented Mar 18, 2014 at 17:40

- 1 $\begingroup$ What I do is to "randomly" select a (small) sample of students for each homework, which then have to explain what they turned in. The grade of the oral is then the grade of the homework. The rationale is that I really don't care if they copied/worked together/found the answer on the 'web, I care that they understand the subject matter. $\endgroup$ – vonbrand Commented Mar 18, 2014 at 21:00

At my university the focus is moved to tests and exams. In larger courses homework has usually no or very little significance, while in smaller classes very few attempt copying (it is too easy to spot).

On the other hand, programming homework is handled via plagiarism software (we have our own, its internals being kept secret; the output is reviewed manually), this is a routine procedure, as homework is usually tested automatically, and it is a standard step in various national-level contests that our university handles.

Now, to answer your question, how to handle copying when it happens? I know of three ways:

- By a formal process. The statute of our university says it's forbidden to do so (I suspect this is not unique), and such a student could be expelled. In practice, as far as I can remember, it had never happened. I heard that there had been such attempt, however, the student council had caused enough trouble that it all had come to nothing. This might have something to do with the fact, that the STEM-campus and the humanities don't like each other very much and the student council is in majority from the latter.

- Fail the course . Some insist that such students shouldn't be allowed to attend the make-up session exam, but this would result in a bureaucratic mess. Instead, by plagiarism the student achieves an equivalent of $-\infty$ points and it all fits into professor's "freedom of grading".

- By some agreement. This might be not the most fair, but during their first semester, it might be the most appropriate. Students come from various neighborhoods, their high-school had different policies and are frequently immature. A good talking-to has more positive effects than punishment, which you could still apply later if he/she hasn't learned from the mistakes. Fortunately, at my university copying is rare enough that we can afford such a lenient treatment (and you don't even need to keep track, because people remember).

I hope this helps $\ddot\smile$

- 3 $\begingroup$ "So, professor, how will this -$\infty$ average into my grade?" $\endgroup$ – Andrew Commented Jan 22, 2016 at 13:54

- 1 $\begingroup$ @Andrew Professor: "Your grade on the exam was 6/10. So your total grade is (winking while writing it down) $-\infty\cdot w+ 6/10\cdot (1-w), \;0<w<1$. If you can tell me "how much that is" I will give you a passing grade." $\endgroup$ – Alecos Papadopoulos Commented Jan 22, 2016 at 15:24

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged undergraduate-education homework or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- Is it possible to accurately describe something without describing the rest of the universe?

- Is the spectrum of Hawking radiation identical to that of thermal radiation?

- Memory-optimizing arduino code to be able to print all files from SD card

- If a trigger runs an update will it ALWAYS have the same timestamp for a temporal table?

- If inflation/cost of living is such a complex difficult problem, then why has the price of drugs been absoultly perfectly stable my whole life?

- How can moral disagreements be resolved when the conflicting parties are guided by fundamentally different value systems?

- "TSA regulations state that travellers are allowed one personal item and one carry on"?

- Why is the movie titled "Sweet Smell of Success"?

- How is it possible to know a proposed perpetual motion machine won't work without even looking at it?

- Maximizing the common value of both sides of an equation

- What explanations can be offered for the extreme see-sawing in Montana's senate race polling?

- What's the meaning of "running us off an embankment"?

- How does the summoned monster know who is my enemy?

- How can judicial independence be jeopardised by politicians' criticism?

- Is there a phrase for someone who's really bad at cooking?

- Background for the Elkies-Klagsbrun curve of rank 29

- AM-GM inequality (but equality cannot be attained)

- Book or novel about an intelligent monolith from space that crashes into a mountain

- How do we reconcile the story of the woman caught in adultery in John 8 and the man stoned for picking up sticks on Sabbath in Numbers 15?

- Why did the Fallschirmjäger have such terrible parachutes?

- I would like to add 9 months onto a field table that is a date and have it populate with the forecast date 9 months later

- magnetic boots inverted

- Suitable Category in which Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem Arises Naturally as Canonical Decomposition

- Parody of Fables About Authenticity

- Our Mission

Why Students Cheat—and What to Do About It

A teacher seeks answers from researchers and psychologists.

“Why did you cheat in high school?” I posed the question to a dozen former students.

“I wanted good grades and I didn’t want to work,” said Sonya, who graduates from college in June. [The students’ names in this article have been changed to protect their privacy.]

My current students were less candid than Sonya. To excuse her plagiarized Cannery Row essay, Erin, a ninth-grader with straight As, complained vaguely and unconvincingly of overwhelming stress. When he was caught copying a review of the documentary Hypernormalism , Jeremy, a senior, stood by his “hard work” and said my accusation hurt his feelings.

Cases like the much-publicized ( and enduring ) 2012 cheating scandal at high-achieving Stuyvesant High School in New York City confirm that academic dishonesty is rampant and touches even the most prestigious of schools. The data confirms this as well. A 2012 Josephson Institute’s Center for Youth Ethics report revealed that more than half of high school students admitted to cheating on a test, while 74 percent reported copying their friends’ homework. And a survey of 70,000 high school students across the United States between 2002 and 2015 found that 58 percent had plagiarized papers, while 95 percent admitted to cheating in some capacity.

So why do students cheat—and how do we stop them?

According to researchers and psychologists, the real reasons vary just as much as my students’ explanations. But educators can still learn to identify motivations for student cheating and think critically about solutions to keep even the most audacious cheaters in their classrooms from doing it again.

Rationalizing It

First, know that students realize cheating is wrong—they simply see themselves as moral in spite of it.

“They cheat just enough to maintain a self-concept as honest people. They make their behavior an exception to a general rule,” said Dr. David Rettinger , professor at the University of Mary Washington and executive director of the Center for Honor, Leadership, and Service, a campus organization dedicated to integrity.

According to Rettinger and other researchers, students who cheat can still see themselves as principled people by rationalizing cheating for reasons they see as legitimate.

Some do it when they don’t see the value of work they’re assigned, such as drill-and-kill homework assignments, or when they perceive an overemphasis on teaching content linked to high-stakes tests.

“There was no critical thinking, and teachers seemed pressured to squish it into their curriculum,” said Javier, a former student and recent liberal arts college graduate. “They questioned you on material that was never covered in class, and if you failed the test, it was progressively harder to pass the next time around.”

But students also rationalize cheating on assignments they see as having value.

High-achieving students who feel pressured to attain perfection (and Ivy League acceptances) may turn to cheating as a way to find an edge on the competition or to keep a single bad test score from sabotaging months of hard work. At Stuyvesant, for example, students and teachers identified the cutthroat environment as a factor in the rampant dishonesty that plagued the school.

And research has found that students who receive praise for being smart—as opposed to praise for effort and progress—are more inclined to exaggerate their performance and to cheat on assignments , likely because they are carrying the burden of lofty expectations.

A Developmental Stage

When it comes to risk management, adolescent students are bullish. Research has found that teenagers are biologically predisposed to be more tolerant of unknown outcomes and less bothered by stated risks than their older peers.

“In high school, they’re risk takers developmentally, and can’t see the consequences of immediate actions,” Rettinger says. “Even delayed consequences are remote to them.”

While cheating may not be a thrill ride, students already inclined to rebel against curfews and dabble in illicit substances have a certain comfort level with being reckless. They’re willing to gamble when they think they can keep up the ruse—and more inclined to believe they can get away with it.

Cheating also appears to be almost contagious among young people—and may even serve as a kind of social adhesive, at least in environments where it is widely accepted. A study of military academy students from 1959 to 2002 revealed that students in communities where cheating is tolerated easily cave in to peer pressure, finding it harder not to cheat out of fear of losing social status if they don’t.

Michael, a former student, explained that while he didn’t need to help classmates cheat, he felt “unable to say no.” Once he started, he couldn’t stop.

Technology Facilitates and Normalizes It

With smartphones and Alexa at their fingertips, today’s students have easy access to quick answers and content they can reproduce for exams and papers. Studies show that technology has made cheating in school easier, more convenient, and harder to catch than ever before.

To Liz Ruff, an English teacher at Garfield High School in Los Angeles, students’ use of social media can erode their understanding of authenticity and intellectual property. Because students are used to reposting images, repurposing memes, and watching parody videos, they “see ownership as nebulous,” she said.

As a result, while they may want to avoid penalties for plagiarism, they may not see it as wrong or even know that they’re doing it.

This confirms what Donald McCabe, a Rutgers University Business School professor, reported in his 2012 book ; he found that more than 60 percent of surveyed students who had cheated considered digital plagiarism to be “trivial”—effectively, students believed it was not actually cheating at all.

Strategies for Reducing Cheating

Even moral students need help acting morally, said Dr. Jason M. Stephens , who researches academic motivation and moral development in adolescents at the University of Auckland’s School of Learning, Development, and Professional Practice. According to Stephens, teachers are uniquely positioned to infuse students with a sense of responsibility and help them overcome the rationalizations that enable them to think cheating is OK.

1. Turn down the pressure cooker. Students are less likely to cheat on work in which they feel invested. A multiple-choice assessment tempts would-be cheaters, while a unique, multiphase writing project measuring competencies can make cheating much harder and less enticing. Repetitive homework assignments are also a culprit, according to research , so teachers should look at creating take-home assignments that encourage students to think critically and expand on class discussions. Teachers could also give students one free pass on a homework assignment each quarter, for example, or let them drop their lowest score on an assignment.

2. Be thoughtful about your language. Research indicates that using the language of fixed mindsets , like praising children for being smart as opposed to praising them for effort and progress , is both demotivating and increases cheating. When delivering feedback, researchers suggest using phrases focused on effort like, “You made really great progress on this paper” or “This is excellent work, but there are still a few areas where you can grow.”

3. Create student honor councils. Give students the opportunity to enforce honor codes or write their own classroom/school bylaws through honor councils so they can develop a full understanding of how cheating affects themselves and others. At Fredericksburg Academy, high school students elect two Honor Council members per grade. These students teach the Honor Code to fifth graders, who, in turn, explain it to younger elementary school students to help establish a student-driven culture of integrity. Students also write a pledge of authenticity on every assignment. And if there is an honor code transgression, the council gathers to discuss possible consequences.

4. Use metacognition. Research shows that metacognition, a process sometimes described as “ thinking about thinking ,” can help students process their motivations, goals, and actions. With my ninth graders, I use a centuries-old resource to discuss moral quandaries: the play Macbeth . Before they meet the infamous Thane of Glamis, they role-play as medical school applicants, soccer players, and politicians, deciding if they’d cheat, injure, or lie to achieve goals. I push students to consider the steps they take to get the outcomes they desire. Why do we tend to act in the ways we do? What will we do to get what we want? And how will doing those things change who we are? Every tragedy is about us, I say, not just, as in Macbeth’s case, about a man who succumbs to “vaulting ambition.”

5. Bring honesty right into the curriculum. Teachers can weave a discussion of ethical behavior into curriculum. Ruff and many other teachers have been inspired to teach media literacy to help students understand digital plagiarism and navigate the widespread availability of secondary sources online, using guidance from organizations like Common Sense Media .

There are complicated psychological dynamics at play when students cheat, according to experts and researchers. While enforcing rules and consequences is important, knowing what’s really motivating students to cheat can help you foster integrity in the classroom instead of just penalizing the cheating.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Academic dishonesty when doing homework: How digital technologies are put to bad use in secondary schools

Juliette c. désiron.

Institute of Education, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

Dominik Petko

Associated data.

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in SISS base at 10.23662/FORS-DS-1285-1, reference number 1285.

The growth in digital technologies in recent decades has offered many opportunities to support students’ learning and homework completion. However, it has also contributed to expanding the field of possibilities concerning homework avoidance. Although studies have investigated the factors of academic dishonesty, the focus has often been on college students and formal assessments. The present study aimed to determine what predicts homework avoidance using digital resources and whether engaging in these practices is another predictor of test performance. To address these questions, we analyzed data from the Program for International Student Assessment 2018 survey, which contained additional questionnaires addressing this issue, for the Swiss students. The results showed that about half of the students engaged in one kind or another of digitally-supported practices for homework avoidance at least once or twice a week. Students who were more likely to use digital resources to engage in dishonest practices were males who did not put much effort into their homework and were enrolled in non-higher education-oriented school programs. Further, we found that digitally-supported homework avoidance was a significant negative predictor of test performance when considering information and communication technology predictors. Thus, the present study not only expands the knowledge regarding the predictors of academic dishonesty with digital resources, but also confirms the negative impact of such practices on learning.

Introduction

Academic dishonesty is a widespread and perpetual issue for teachers made even more easier to perpetrate with the rise of digital technologies (Blau & Eshet-Alkalai, 2017 ; Ma et al., 2008 ). Definitions vary but overall an academically dishonest practices correspond to learners engaging in unauthorized practice such as cheating and plagiarism. Differences in engaging in those two types of practices mainly resides in students’ perception that plagiarism is worse than cheating (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; McCabe, 2005 ). Plagiarism is usually defined as the unethical act of copying part or all of someone else’s work, with or without editing it, while cheating is more about sharing practices (Krou et al., 2021 ). As a result, most students do report cheating in an exam or for homework (Ma et al., 2008 ). To note, other research follow a different distinction for those practices and consider that plagiarism is a specific – and common – type of cheating (Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). Digital technologies have contributed to opening possibilities of homework avoidance and technology-related distraction (Ma et al., 2008 ; Xu, 2015 ).

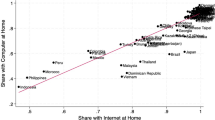

The question of whether the use of digital resources hinders or enhances homework has often been investigated in large-scale studies, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). While most of the early large-scale studies showed positive overall correlations between the use of digital technologies for learning at home and test scores in language, mathematics, and science (e.g., OECD, 2015 ; Petko et al., 2017 ; Skryabin et al., 2015 ), there have been more recent studies reporting negative associations as well (Agasisti et al., 2020 ; Odell et al., 2020 ). One reason for these inconclusive findings is certainly the complex interplay of related factors, which include diverse ways of measuring homework, gender, socioeconomic status, personality traits, learning goals, academic abilities, learning strategies, motivation, and effort, as well as support from teachers and parents. Despite this complexity, it needs to be acknowledged that doing homework digitally does not automatically lead to productive learning activities, and it might even be associated with counter-productive practices such as digital distraction or academic dishonesty. Digitally enhanced academic dishonesty has mostly been investigated regarding formal assessment-related examinations (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ); however, it might be equally important to investigate its effects regarding learning-related assignments such as homework. Although a large body of research exists on digital academic dishonesty regarding assignments in higher education, relatively few studies have investigated this topic on K12 homework. To investigate this issue, we integrated questionnaire items on homework engagement and digital homework avoidance in a national add-on to PISA 2018 in Switzerland. Data from the Swiss sample can serve as a case study for further research with a wider cultural background. This study provides an overview of the descriptive results and tries to identify predictors of the use of digital technology for academic dishonesty when completing homework.

Prevalence and factors of digital academic dishonesty in schools

According to Pavela’s ( 1997 ) framework, four different types of academic dishonesty can be distinguished: cheating by using unauthorized materials, plagiarism by copying the work of others, fabrication of invented evidence, and facilitation by helping others in their attempts at academic dishonesty. Academic dishonesty can happen in assessment situations, as well as in learning situations. In formal assessments, academic dishonesty usually serves the purpose of passing a test or getting a better grade despite lacking the proper abilities or knowledge. In learning-related situations such as homework, where assignments are mandatory, cheating practices equally qualify as academic dishonesty. For perpetrators, these practices can be seen as shortcuts in which the willingness to invest the proper time and effort into learning is missing (Chow, 2021; Waltzer & Dahl, 2022 ). The interviews by Waltzer & Dahl ( 2022 ) reveal that students do perceive cheating as being wrong but this does not prevent them from engaging in at least one type of dishonest practice. While academic dishonesty is not a new phenomenon, it has been changing together with the development of new digital technologies (Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004 ). With the rapid growth in technologies, new forms of homework avoidance, such as copying and plagiarism, are developing (Evering & Moorman, 2012 ; Ma et al., 2008 ) summarized the findings of the 2006 U.S. surveys of the Josephson Institute of Ethics with the conclusion that the internet has led to a deterioration of ethics among students. In 2006, one-third of high school students had copied an internet document in the past 12 months, and 60% had cheated on a test. In 2012, these numbers were updated to 32% and 51%, respectively (Josephson Institute of Ethics, 2012 ). Further, 75% reported having copied another’s homework. Surprisingly, only a few studies have provided more recent evidence on the prevalence of academic dishonesty in middle and high schools. The results from colleges and universities are hardly comparable, and until now, this topic has not been addressed in international large-scale studies on schooling and school performance.

Despite the lack of representative studies, research has identified many factors in smaller and non-representative samples that might explain why some students engage in dishonest practices and others do not. These include male gender (Whitley et al., 1999 ), the “dark triad” of personality traits in contrast to conscientiousness and agreeableness (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2021 ; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015 ), extrinsic motivation and performance/avoidance goals in contrast to intrinsic motivation and mastery goals (e.g., Anderman & Koenka, 2017 ; Krou et al., 2021 ), self-efficacy and achievement scores (e.g., Nora & Zhang, 2010 ; Yaniv et al., 2017 ), unethical attitudes, and low fear of being caught (e.g., Cheng et al., 2021 ; Kam et al., 2018 ), influenced by the moral norms of peers and the conditions of the educational context (e.g., Isakov & Tripathy, 2017 ; Kapoor & Kaufman, 2021 ). Similar factors have been reported regarding research on the causes of plagiarism (Husain et al., 2017 ; Moss et al., 2018 ). Further, the systematic review from Chiang et al. ( 2022 ) focused on factors of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. The analyses, based on the six-components behavior engineering, showed that the most prominent factors were environmental (effect of incentives) and individual (effect of motivation). Despite these intensive research efforts, there is still no overarching model that can comprehensively explain the interplay of these factors.

Effects of homework engagement and digital dishonesty on school performance

In meta-analyses of schools, small but significant positive effects of homework have been found regarding learning and achievement (e.g., Baş et al., 2017 ; Chen & Chen, 2014 ; Fan et al., 2017 ). In their review, Fan et al. ( 2017 ) found lower effect sizes for studies focusing on the time or frequency of homework than for studies investigating homework completion, homework grades, or homework effort. In large surveys, such as PISA, homework measurement by estimating after-school working hours has been customary practice. However, this measure could hide some other variables, such as whether teachers even give homework, whether there are school or state policies regarding homework, where the homework is done, whether it is done alone, etc. (e.g., Fernández-Alonso et al., 2015 , 2017 ). Trautwein ( 2007 ) and Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) repeatedly showed that homework effort rather than the frequency or the time spent on homework can be considered a better predictor for academic achievement Effort and engagement can be seen as closely interrelated. Martin et al. ( 2017 ) defined engagement as the expressed behavior corresponding to students’ motivation. This has been more recently expanded by the notion of the quality of homework completion (Rosário et al., 2018 ; Xu et al., 2021 ). Therefore, it is a plausible assumption that academic dishonesty when doing homework is closely related to low homework effort and a low quality of homework completion, which in turn affects academic achievement. However, almost no studies exist on the effects of homework avoidance or academic dishonesty on academic achievement. Studies investigating the relationship between academic dishonesty and academic achievement typically use academic achievement as a predictor of academic dishonesty, not the other way around (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2019 ; McCabe et al., 2001 ). The results of these studies show that low-performing students tend to engage in dishonest practices more often. However, high-performing students also seem to be prone to cheating in highly competitive situations (Yaniv et al., 2017 ).

Present study and hypotheses

The present study serves three combined purposes.

First, based on the additional questionnaires integrated into the Program for International Student Assessment 2018 (PISA 2018) data collection in Switzerland, we provide descriptive figures on the frequency of homework effort and the various forms of digitally-supported homework avoidance practices.

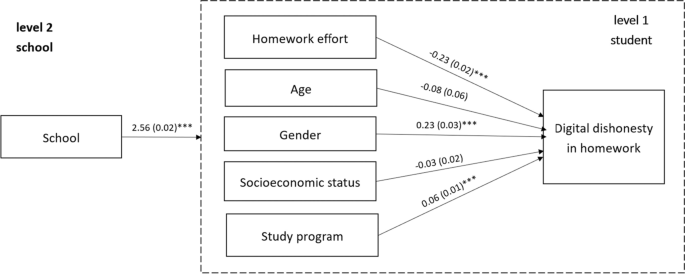

Second, the data were used to identify possible factors that explain higher levels of digitally-supported homework avoidance practices. Based on our review of the literature presented in Section 1.1 , we hypothesized (Hypothesis 1 – H1) that these factors include homework effort, age, gender, socio-economic status, and study program.

Finally, we tested whether digitally-supported homework avoidance practices were a significant predictor of test score performance. We expected (Hypothesis 2 – H2) that technology-related factors influencing test scores include not only those reported by Petko et al. ( 2017 ) but also self-reported engagement in digital dishonesty practices. .

Participants

Our analyses were based on data collected for PISA 2018 in Switzerland, made available in June 2021 (Erzinger et al., 2021 ). The target sample of PISA was 15-year-old students, with a two-phase sampling: schools and then students (Erzinger et al., 2019 , p.7–8, OECD, 2019a ). A total of 228 schools were selected for Switzerland, with an original sample of 5822 students. Based on the PISA 2018 technical report (OECD, 2019a ), only participants with a minimum of three valid responses to each scale used in the statistical analyses were included (see Section 2.2 ). A final sample of 4771 responses (48% female) was used for statistical analyses. The mean age was 15 years and 9 months ( SD = 3 months). As Switzerland is a multilingual country, 60% of the respondents completed the questionnaires in German, 23% in French, and 17% in Italian.

Digital dishonesty in homework scale

This six-item digital dishonesty for homework scale assesses the use of digital technology for homework avoidance and copying (IC801 C01 to C06), is intended to work as a single overall scale for digital homework dishonesty practice constructed to include items corresponding to two types of dishonest practices from Pavela ( 1997 ), namely cheating and plagiarism (see Table 1 ). Three items target individual digital practices to avoid homework, which can be referred to as plagiarism (items 1, 2 and 5). Two focus more on social digital practices, for which students are cheating together with peers (items 4 and 6). One item target cheating as peer authorized plagiarism. Response options are based on questions on the productive use of digital technologies for homework in the common PISA survey (IC010), with an additional distinction for the lowest frequency option (6-point Likert scale). The scale was not tested prior to its integration into the PISA questionnaire, as it was newly developed for the purposes of this study.

Frequencies of averaged digital dishonesty in homework (weighted data)

| Never | Almost never | Once or twice a month | Once or twice a week | Almost every day | Every day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … I partially copy things from the internet and modify them so that no one notices. | 23.8% | 29.0% | 24.9% | 15.0% | 4.4% | 2.9% |

| … I look on the internet for summaries or answers, so that I don’t have to do so much work myself. | 20.3% | 25.8% | 27.9% | 18.4% | 5.0% | 2.7% |

| … I copy friends’ answers, which they send me online or by phone. | 15.7% | 22.6% | 28.1% | 23.5% | 6.9% | 3.2% |

| … I do the homework on the internet together with others, even though I should be working on my own. | 34.6% | 22.9% | 18.6% | 15.4% | 6.0% | 2.6% |

| … I copy something from the internet and simply hand it in as my own work. | 51.7% | 19.7% | 11.2% | 10.3% | 4.5% | 2.7% |

| … I share my homework with others via the internet, so that people don’t have to do everything themselves. | 32.4% | 21.4% | 19.7% | 15.7% | 6.6% | 4.2% |

| Digital dishonesty (all practices considered) | 7.6% | 15.1% | 27.7% | 30.6% | 12.1% | 6.9% |

Homework engagement scale

The scale, originally developed by Trautwein et al. (Trautwein, 2007 ; Trautwein et al., 2006 ), measures homework engagement (IC800 C01 to C06) and can be subdivided into two sub-scales: homework compliance and homework effort. The reliability of the scale was tested and established in different variants, both in Germany (Trautwein et al., 2006 ; Trautwein & Köller, 2003 ) and in Switzerland (Schnyder et al., 2008 ; Schynder Godel, 2015 ). In the adaptation used in the PISA 2018 survey, four items were positively poled (items 1, 2, 4, and 6), and two items were negatively poled (items 3 and 5) and presented with a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Does not apply at all” to “Applies absolutely.” This adaptation showed acceptable reliability in previous studies in Switzerland (α = 0.73 and α = 0.78). The present study focused on homework effort, and thus only data from the corresponding sub-scale was analyzed (items 2 [I always try to do all of my homework], 4 [When it comes to homework, I do my best], and 6 [On the whole, I think I do my homework more conscientiously than my classmates]).

Demographics

Previous studies showed that demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status, could impact learning outcomes (Jacobs et al., 2002 ) and intention to use digital tools for learning (Tarhini et al., 2014 ). Gender is a dummy variable (ST004), with 1 for female and 2 for male. Socioeconomic status was analyzed based on the PISA 2018 index of economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS). It is computed from three other indices (OECD, 2019b , Annex A1): parents’ highest level of education (PARED), parents’ highest occupational status (HISEI), and home possessions (HOMEPOS). The final ESCS score is transformed so that 0 corresponds to an average OECD student. More details can be found in Annex A1 from PISA 2018 Results Volume 3 (OECD, 2019b ).

Study program

Although large-scale studies on schools have accounted for the differences between schools, the study program can also be a factor that directly affects digital homework dishonesty practices. In Switzerland, 15-year-old students from the PISA sampling pool can be part of at least six main study programs, which greatly differ in terms of learning content. In this study, study programs distinguished both level and type of study: lower secondary education (gymnasial – n = 798, basic requirements – n = 897, advanced requirements – n = 1235), vocational education (classic – n = 571, with baccalaureate – n = 275), and university entrance preparation ( n = 745). An “other” category was also included ( n = 250). This 6-level ordinal variable was dummy coded based on the available CNTSCHID variable.

Technologies and schools

The PISA 2015 ICT (Information and Communication Technology) familiarity questionnaire included most of the technology-related variables tested by Petko et al. ( 2017 ): ENTUSE (frequency of computer use at home for entertainment purposes), HOMESCH (frequency of computer use for school-related purposes at home), and USESCH (frequency of computer use at school). However, the measure of student’s attitudes toward ICT in the 2015 survey was different from that of the 2012 dataset. Based on previous studies (Arpacı et al., 2021 ; Kunina-Habenicht & Goldhammer, 2020 ), we thus included INICT (Student’s ICT interest), COMPICT (Students’ perceived ICT competence), AUTICT (Students’ perceived autonomy related to ICT use), and SOIACICT (Students’ ICT as a topic in social interaction) instead of the variable ICTATTPOS of the 2012 survey.

Test scores

The PISA science, mathematics, and reading test scores were used as dependent variables to test our second hypothesis. Following Aparicio et al. ( 2021 ), the mean scores from plausible values were computed for each test score and used in the test score analysis.

Data analyses

Our hypotheses aim to assess the factors explaining student digital homework dishonesty practices (H1) and test score performance (H2). At the student level, we used multilevel regression analyses to decompose the variance and estimate associations. As we used data for Switzerland, in which differences between school systems exist at the level of provinces (within and between), we also considered differences across schools (based on the variable CNTSCHID).

Data were downloaded from the main PISA repository, and additional data for Switzerland were available on forscenter.ch (Erzinger et al., 2021 ). Analyses were computed with Jamovi (v.1.8 for Microsoft Windows) statistics and R packages (GAMLj, lavaan).

Additional scales for Switzerland

Digital dishonesty in homework practices.

The digital homework dishonesty scale (6 items), computed with the six items IC801, was found to be of very good reliability overall (α = 0.91, ω = 0.91). After checking for reliability, a mean score was computed for the overall scale. The confirmatory factor analysis for the one-dimensional model reached an adequate fit, with three modifications using residual covariances between single items χ 2 (6) = 220, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.969, CFI = 0.988, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.086, SRMR = 0.016).

On the one hand, the practice that was the least reported was copying something from the internet and presenting it as their own (51% never did). On the other hand, students were more likely to partially copy content from the internet and modify it to present as their own (47% did it at least once a month). Copying answers shared by friends was rather common, with 62% of the students reporting that they engaged in such practices at least once a month.

When all surveyed practices were taken together, 7.6% of the students reported that they had never engaged in digitally dishonest practices for homework, while 30.6% reported cheating once or twice a week, 12.1% almost every day, and 6.9% every day (Table 1 ).

Homework effort

The overall homework engagement scale consisted of six items (IC800), and it was found to be acceptably reliable (α = 0.76, ω = 0.79). Items 3 and 5 were reversed for this analysis. The homework compliance sub-scale had a low reliability (α = 0.58, ω = 0.64), whereas the homework effort sub-scale had an acceptable reliability (α = 0.78, ω = 0.79). Based on our rationale, the following statistical analyses used only the homework effort sub-scale. Furthermore, this focus is justified by the fact that the homework compliance scale might be statistically confounded with the digital dishonesty in homework scale.

Descriptive weighted statistics per item (Table 2 ) showed that while most students (80%) tried to complete all of their homework, only half of the students reported doing those diligently (53.3%). Most students also reported that they believed they put more effort into their homework than their peers (77.7%). The overall mean score of the composite scale was 2.81 ( SD = 0.69).

Frequencies of averaged homework engagement (weighted data)

| Does not apply at all | Does not apply to a great extent | Applies to a certain extent | Applies absolutely | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I always try to do all of my homework. | 5.0% | 17.8% | 44.8% | 32.4% |

| When it comes to homework, I do my best. | 5.6% | 24.8% | 51.2% | 18.4% |

| On the whole, I think I do my homework more conscientiously than my classmates. | 12.8% | 35.0% | 39.6% | 12.7% |

Multilevel regression analysis: Predictors of digital dishonesty in homework (H1)

Mixed multilevel modeling was used to analyze predictors of digital homework avoidance while considering the effect of school (random component). Based on our first hypothesis, we compared several models by progressively including the following fixed effects: homework effort and personal traits (age, gender) (Model 2), then socio-economic status (Model 3), and finally, study program (Model 4). The results are presented in Table 3 . Except for the digital homework dishonesty and homework efforts scales, all other scales were based upon the scores computed according to the PISA technical report (OECD, 2019a ).

Multilevel models explaining variations in students’ self-reported homework avoidance with digital resources

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects (β) | ||||

| Homework effort | -0.22 | -0.22 | -0.23 | |

| Age | -0.03 | -0.03 | -0.08 | |

| Gender | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.23 | |

| Socioeconomic status | -0.05 | 0.03 | ||

| Study program | 0.06 | |||

| Models’ parameters | ||||

| Conditional R | 0.066 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 0.101 |

| Marginal R | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.044 | |

| b | 2.56 | 2.56 | 2.56 | 2.56 |

| SE b | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| 95% CI | 2.52, 2.61 | 2.51, 2.61 | 2.51, 2.61 | 2.51, 2.61 |

| AIC | 14465.49 | 13858.83 | 13715.70 | 13694.45 |

| ICC | 0.066 | 0.071 | 0.067 | 0.065 |

Note : * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

We first compared variance components. Variance was decomposed into student and school levels. Model 1 provides estimates of the variance component without any covariates. The intraclass coefficient (ICC) indicated that about 6.6% of the total variance was associated with schools. The parameter (b = 2.56, SE b = 0.025 ) falls within the 95% confidence interval. Further, CI is above 0 and thus we can reject the null hypothesis. Comparing the empty model to models with covariates, we found that Models 2, 3 and 4 showed an increase in total explained variance to 10%. Variance explained by the covariates was about 3% in Models 2 and 3, and about 4% in Model 4. Interestingly, in our models, student socio-economic status, measured by the PISA index, never accounted for variance in digitally-supported dishonest practices to complete homework.

Further, model comparison based on AIC indicates that Model 4, including homework effort, personal traits, socio-economic status, and study program, was the better fit for the data. In Model 4 (Table 3 ; Fig. 1 ), we observed that homework effort and gender were negatively associated with digital dishonesty. Male students who invested less effort in their homework were more prone to engage in digital dishonesty. The study program was positively but weakly associated with digital dishonesty. Students in programs that target higher education were less likely to engage in digital dishonesty when completing homework.

Summary of the two-steps Model 4 (estimates - β, with standard errors and significance levels, *** p < 0.001)

Multilevel regression analysis: Cheating and test scores (H2)

Our first hypothesis aimed to provide insights into characteristics of students reporting that they regularly use digital resources dishonestly when completing homework. Our second hypothesis focused on whether digitally-supported homework avoidance practices was linked to results of test scores. Mixed multilevel modeling was used to analyze predictors of test scores while considering the effect of school (random component). Based on the study by Petko et al. ( 2017 ), we compared several models by progressively including the following fixed effects ICT use (three measures) (Model 2), then attitude toward ICT (four measures) (Model 3), and finally, digital dishonesty in homework (single measure) (Model 4). The results are presented in Table 4 for science, Table 5 for mathematics, and Table 6 for reading.

Multilevel models explaining variations in student test scores in science (standardized coefficients and model parameters)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects (β) | ||||

| ENTUSE | 1.84 | -2.16 | -1.02 | |

| HOMESCH | -12.05 | -10.80 | -9.87 | |

| USESCH | -5.81 | -6.04 | -3.53 | |

| INTICT | 2.24 | 2.54 | ||

| COMPICT | 6.35 | 6.50 | ||

| AUTICT | 9.95 | 9.75 | ||

| SOIAICT | -7.68 | -5.93 | ||

| Digital dishonesty | -10.30 | |||

| Models’ parameters | ||||

| Conditional R | 0.379 | 0.405 | 0.408 | 0.411 |

| Marginal R | 0.025 | 0.051 | 0.069 | |

| b | 495 | 496.48 | 497.68 | 498 |

| SE b | 3.82 | 3.79 | 3.64 | 3.55 |

| 95% CI | 487, 502 | 489.05, 503.92 | 490.55, 504.81 | 491.05, 504.95 |

| AIC | 54619.43 | 52391.74 | 51309.22 | 51208.48 |

| ICC | 0.379 | 0.389 | 0.376 | 0.368 |

Multilevel models explaining variations in student test scores in mathematics (standardized coefficients and model parameters)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects (β) | ||||

| ENTUSE | 1.82 | -1.57 | -0.56 | |

| HOMESCH | -10.45 | -9.88 | -9.05 | |

| USESCH | -4.44 | -4.68 | -2.461 | |

| INTICT | 0.380 | 0.648 | ||

| COMPICT | 5.440 | 5.566 | ||

| AUTICT | 7.157 | 6.982 | ||

| SOIAICT | -3.416 | -1.876 | ||

| Digital dishonesty | -9.102 | |||

| Models’ parameters | ||||

| Conditional R | 0.388 | 0.408 | 0.410 | 0.412 |

| Marginal R | 0.019 | 0.034 | 0.048 | |

| b | 516 | 516.84 | 517.81 | 518.09 |

| SE b | 3.70 | 3.69 | 3.60 | 3.51 |

| 95% CI | 508, 523 | 509.61, 524.07 | 510.76, 524.86 | 511.20,524.98 |

| AIC | 54139.46 | 52009.23 | 50985.87 | 50901.03 |

| ICC | 0.388 | 0.397 | 0.389 | 0.382 |

Multilevel models explaining variations in student test scores in reading (standardized coefficients and model parameters)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||

| ENTUSE | -1.97 | -5.07 | -3.52 | |

| HOMESCH | -13.12 | -11.23 | -9.97 | |

| USESCH | -6.7 | -6.67 | -3.28 | |

| INTICT | 7.38 | 7.79 | ||

| COMPICT | 4.04 | 4.23 | ||

| AUTICT | 9.02 | 8.75 | ||

| SOIAICT | -12.16 | -9.79 | ||

| Digital dishonesty | -13.94 | |||

| Models’ parameters | ||||

| Conditional R | 0.381 | 0.410 | 0.413 | 0.422 |

| Marginal R | 0.032 | 0.061 | 0.088 | |

| b | 485 | 486.88 | 488.44 | 488.86 |

| SE b | 4.12 | 4.06 | 3.87 | 3.74 |

| 95% CI | 477, 493 | 478.91, 494.84 | 480.86, 496.02 | 481.54, 496.18 |

| AIC | 55305.13 | 53003.48 | 51871.13 | 51705.75 |