- Youth Program

- Wharton Online

Wharton Stories

Wharton hq case study: building an online community for admits.

Every year, newly admitted Wharton MBA students or “admits” travel to Philadelphia to spend three days at Spring Welcome Weekend. The weekend helps admits (plus their spouses and partners) decide if Wharton is where they feel the most at home. The weekend is also the first step the new MBA class takes to becoming unified, forming connections that will last for decades.

This year, that all changed. Like the rest of the world, the Wharton School was massively disrupted by the coronavirus outbreak. Students were sent home, the remainder of the academic year was moved online, and all in-person events were canceled — including Spring Welcome Weekend.

How could we still provide the same information, benefits, and connections, virtually, in a way that had never been done before? It became clear we needed to build an online community.

Choosing the Right Platform

Wharton’s Marketing Technology team, part of the larger Marketing and Communications group, got to work brainstorming ideas. With limited time, we wouldn’t be able to complete the technological build required for a Salesforce Community. A private Facebook Group was ruled out because it wouldn’t allow for topics to be broken into separate discussion areas or be accessible in all countries. One team member suggested Workplace by Facebook — a ready-made communications platform for teams with many of the familiar features of Facebook itself. With the same User Interface formulas (likes, comments, posts, groups, the News Feed) we knew our admitted students would have a short learning curve after logging on for the first time.

Here are a few other key features and how we used them:

- Groups: We created 13 official groups around common areas of interest, such as “Housing,” “Life in Philadelphia,” “Financial Aid,” and “MBA Announcements” were organized into their own Groups. Groups can be open to anyone or invite-only.

- News Feed: A running stream of posts from other members and Groups.

- Events: Allowed our team to schedule events with the option to RSVP.

- Resources and Knowledge Library: Links and articles relevant to admitted students.

- Directory: Admitted students could easily search and find other admits and connect with them.

- Chat: Admits and staff could chat privately with one another or in small groups.

- Insights: A dashboard for administrators to see the health of the community and confirm that important content was seen.

Breathing Life into the Community

From a technology perspective, we felt confident about the use of Workplace. But a successful online community is much more than a platform; it’s also about how you ensure that it’s a place where members want to be and contribute to. We added this human element in three ways:

- The “Introduce Yourself” group was a way for admitted students to get to know each other. Prior to the launch, our team modeled the behavior we wanted to see by sharing photos and personalities.

- A team of more than 60 student ambassadors called the Student Life Fellows (SLFs) were already prepared to lead the in-person Welcome Weekend. Now on Wharton HQ they were mobilized to support the three-weeks of programming online — jumping in to answer questions, make connections and introductions, and keep conversations going. A few SLFs hosted apartment tours to give admits a look at life in Philadelphia — something we could have never done with an in-person event!

- We compiled content from our own archives and third-party sources into a spreadsheet for staff and SLFs to easily access when questions from admits popped up.

- Blair Mannix, Director of Admissions, recorded a selfie video (see above) that was “pinned” to the News Feed as the first post members would see after joining. In this video, Blair pointed out ways to get in touch and encouraged new members to take high-priority actions — introduce yourself, join groups, and connect with each other.

Learning Point: Make sure you have people on standby ready to comment on and like posts from new members. Doing this makes new members feel welcome, and encourages them to comment and like other people’s posts, thereby amplifying the effect.

The Game Plan

To stay organized, we worked from one massive, continually updated Google Sheet which outlined Groups, Events, the staff and student teams, ideas to brainstorm, and engagement efforts. The spreadsheet also housed a communications flow and a variety of content calendars. We also created an internal Slack channel to surface questions and keep everyone updated.

Learning Point: It is important to think through and document the who, what, where, why, and when of the various ways that your team will engage with the community and its members. A simple spreadsheet is an excellent way to do this and to get everyone, literally, on the same page.

Launch & Results

Within 30 minutes of sending the first email, we could see accounts being claimed and activity in the “Introduce Yourself” group. By the end of the first day, nearly 60 percent of the invited accounts had been claimed. After one week, 75 percent of the accounts were activated.

The next several weeks were a rush of activity on all fronts. Staff, faculty, and current students held dozens of live video sessions and answered hundreds of questions. Admitted students connected with one another, current students, and staff, and kept coming back to learn more and to welcome new members of the community.

Over the course of three weeks:

- More than 250,000 connections were made in a community of about 1,500 people. A connection is any post, like, comment, or private message.

- The average Wharton HQ member made 178 connections.

- About 21,000 instant messages were sent on the platform.

- More than 100 virtual events were hosted by staff, current students, and even alumni for the first time.

This current reality requires us to invent solutions and engage with each other in new, virtual ways. It’s possible — and even rewarding — with the right platform, flexible processes, and full team support.

— Eric Greenberg, Sr. Director of Marketing Strategy and Operations, The Wharton School

Posted: May 29, 2020

- Philadelphia

MBA Program

Building out Wharton HQ did not come without its challenges. Here are four hurdles we encountered:

1. Domain Linking

While validating Workplace, we immediately ran into our first hurdle: domain linking. It turns out that someone had, years ago, created a Facebook Workplace for the wharton.upenn.edu domain. No one we contacted knew who or how to reclaim this dormant community. This forced us down the path of having to purchase a custom domain and the accompanying email accounts. We chose whartonmbawelcome.com, registered it, created our new Workplace, and called it “Wharton HQ.”

Learning Point: Every Facebook Workplace is required to be associated with a domain that you can validate to prove ownership. The email you use to administer the Workplace must also use the same domain.

2. Email Addresses

Workplace is, by design, meant for use by an organization’s staff. Therefore, we could not invite people to the community using the email addresses we had on file because their email may already be tied to a Workplace which would then force them into their existing Workplace and not “Wharton HQ.”

Fortunately, Workplace provides an alternative. We added members to the community and generated “access codes” for them, which we then emailed to the invitees from our email platform, with explicit instructions to use the access code and not log in with an email.

Learning Point: Facebook Workplace allows members to log in with their email address when the email domain is associated with the Workplace domain. Otherwise, a member needs to login with an Access Code.

3. Video Streaming

We also tested live video options with staff. Facebook Workplace comes with the ability to stream live video using the standard Facebook Live option. But it also comes with the ability to integrate a variety of popular video conferencing apps, such as Zoom and BlueJeans. All videos are recorded and automatically made available to members who may have missed it the first time around. We made sure all hosts were comfortable with the technology prior to launch.

Learning Point: Each video streaming option comes with pros and cons. If you need to present slides or pass hosting between people then you will need to use an external video conferencing platform. But for someone presenting solo, or showing off housing options, Facebook Live works wonderfully.

4. Branding

As our team drafted emails to invite admitted students, it became clear that we didn’t have a consistent name for our Facebook Workplace. “Wharton MBA Virtual Welcome Weekend” was too clunky. “Wharton HQ” was selected to retain the Wharton identity as well as succinctly communicate the purpose of the platform. The visual branding opportunities were limited to what Facebook Workplace has built-in to the platform. To create a consistent look, we took advantage of every customizable feature — especially custom group cover photos. We even developed “badges” for users to add to their profile photos using the “Profile Frames” bot.

Learning Point: When introducing something new, it’s important to be open to change. What once made sense for an in-person event, may no longer work for a virtual one.

Related Content

What to Know About the Moelis Advance Access Program Before You Apply

How the Turner MIINT Program Trains Students to Think Like Impact Investors

6 Lessons Learned From a Wharton Undergrad’s Social Entrepreneurial Journey

How Mentorship Enables the Transition from PhD Student to Research Colleague

MBA Students Head to Beijing for an Immersive Learning Experience on Marketing to the Chinese Consumer

Celebrating International Women’s Day: 2021

Meet the 2018 Bendheim Loan Forgiveness Recipients

The Future Can Be Female

‘Surf Club Girl’ Is Riding the Waves at Penn

Undergrad Reflects on Recruiting Process: Part 1, The First Lesson

Highlights and Surprises from EMBA Orientation Week 2019

A Wharton Undergraduate Leadership Odyssey in Patagonia

Solving Society’s Biggest Problems, Starting with Cross-Sector Collaboration

6 Pieces of Advice for New Entrepreneurs in China — and Beyond

Wharton EMBA Program Helps Doctor Save Medical Practice

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, articles in this collection, acknowledgments, online communities: design, theory, and practice.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jenny Preece, Diane Maloney-Krichmar, Online Communities: Design, Theory, and Practice, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 10, Issue 4, 1 July 2005, JCMC10410, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00264.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This special thematic section of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication brings together nine articles that provide a rich composite of the current research in online communities. The articles cover a range of topics, methodologies, theories and practices. Indirectly they all speak to design since they aim to extend our understanding of the field. The variety shown in these articles illustrates how broad the definition is of this rapidly growing field known as ‘online communities.’

Community has become the ‘in-term’ for almost any group of people who use Internet technologies to communicate with each other. Depending on whether one takes a social perspective or a technology perspective, online communities tend to be named by the activity and people they serve or the technology that supports them. For example the same community might be called a ‘breast cancer patient support community’ and a ‘bulletin board community.’ There is much angst about use of the term ‘community,’ especially when researchers from a range disciplines come together, each wanting to place a stake in the ground to support their own goals and research paradigm. Sociologists, social psychologists and anthropologists are the guardians of the term but for more than 50 years, they been have defining and redefining the concept of community ( Wellman, 1982 ).

Until the advent of telecommunications technology, definitions of community focused on close-knit groups in a single location. Factors such as birth and physical location determined belonging to a community. Interaction took place primarily face-to-face; therefore, social relationships took place with a stable and limited set of individuals ( Gergen, 1997 ; Jones, 1997 ). This way of defining community became less useful as the development of modern transportation and telecommunication systems increased personal mobility and reduced the costs of communicating across distances. Newcomers hankering after definitive definitions, and failing to find them, created their own. Researchers now consider the strength and nature of relationships between individuals to be a more useful basis for defining community than physical proximity ( Hamman, 1999 ; Haythornthwaite & Wellman, 1998 ; Wellman, 1997 ; Wellman & Gulia, 1999a ).

Pioneers of online community development and research Howard Rheingold (1993 ) and Roxanne Hiltz (1985) used the term ‘online community’ to connote the intense feelings of camaraderie, empathy and support that they observed among people in the online spaces they studied. Other researchers have attempted to operationalize the term so that it is useful in the analysis, design, and evaluation of community software platforms and management practices ( de Souza & Preece, 2004 ; Maloney-Krichmar & Preece, 2005 ; Preece, 2000 ). These researchers focus on ‘the people who come together for a particular purpose , and who are guided by policies (including norms and rules) and supported by software .’ Others researchers have identified key parameters of community life and then looked for their presence online.

However, as Amy Bruckman pointed out at a recent meeting “ much ink has been spilled trying to work out which online communities are really communities ” (Bruckman, 2005). Bruckman proceeds to argue that expending energy and time on developing definitions may not be the best way to proceed. She suggests that a more productive approach may be to accept community as a concept with fuzzy boundaries that is perhaps more appropriately defined by its membership. This can be done by noting the similarities and differences of each new member and comparing them with the characteristics of members who are regarded as being within the community. In many respects this approach lends itself more readily to the way most of us think about the communities that make up our everyday lives. While such approaches to definition might be hard for some academics to accept, they may encourage us to concentrate on more substantive issues such as how communities are created, evolve or cease to exist online.

A related issue is ‘how do we define community boundaries online?’‘Online community’ is a legacy term that is engrained in Internet culture. But increasingly it is accepted that online communities rarely exist only online; many have off-line physical components. Either they start as face-to-face communities and then part or all of the community migrates on to digital media, or conversely, members of an online community seek to meet face-to-face. Communication is hardly ever restricted to a single medium; usually several media are used depending on what is most convenient at the time, which can make doing research in this field difficult. Populations tend not to be bounded, so getting a clear picture of the community's context can be difficult, and sampling is tricky and prone to error.

In order to study online communities, researchers have had to adapt methodologies for use online. Ethnography was used by many early researchers ( Baym, 1993 , 2000 ; Hine, 2000 ) to try to understand issues such as what people do in online spaces, how they express themselves, what motivates them, how they govern themselves, what attracts people to participate, and why some people prefer to observe rather than contribute. Ethnography was an obvious candidate for developing a broad understanding of online behavior within particular contexts. Content and linguistic analysis techniques were modified for analyzing computer-mediated communication ( Herring, 1992 , 2004 ) and social network analysis ( Wellman & Gulia, 1999a , 1999b ) was also applied to online populations, often supported by visualizations that enable researchers to view the network from different perspectives ( Sack, 2000 ). A variety of other creative and innovative visualization techniques have emerged more recently that enable researchers to see and explore community activity at a glance, such as a tool called history flow which reveals the chronology of authorship in wikipedia ( Viégas, Wattenberg, & Dave, 2004 ). Online interviews and questionnaires are also fundamental tools for online community research, despite problems associated with drawing scientific samples and low response rates ( Andrews, Nonnecke, & Preece, 2003 ). Data logging has also been popular.

Just as researchers have borrowed and adapted methods for online work, theories from long-standing traditional research fields have also been applied in online community research, as can be seen from several of the articles in this special collection. These theories have been drawn mostly from the social sciences, particularly sociology, anthropology, social psychology and linguistics. No particular theory or set of theories currently dominates research on online communities. Rather we see the application of different theories that have been selected based on the disciplinary training of the researchers applying them. As new and novel practices emerge within the online community environments, researchers broaden their perspectives as they seek to understand and explain online community dynamics and their effects on people, organizations and cultures.

The call inviting contributions for this special collection identified design , theory and practice as key issues for authors to address. Over sixty abstracts were received from authors working in 13 different countries. These researchers belong to a range of disciplines including: advertising, business, communications, information studies, information systems, psychology, sociology, and research and development groups in companies. The range of topics covered speaks of the broad and growing number of researchers who are now working on this topic.

The abstracts were reviewed and the authors of nineteen were invited to submit full manuscripts. Each of these nineteen manuscripts was then reviewed by three or more reviewers and rated using the JCMC reviewer guidelines. The final nine articles that were accepted went through yet another round of revisions before being accepted for publication. The articles that follow provide a rich slice of the current research in online communities. They cover a range of topics, methodologies, theories and practices. Indirectly they all speak to design since they aim to extend our understanding of the field, though few attempt to directly address practical design issues, which is an important topic for future research. The variety shown in these nine articles illustrates how broad definition is of this rapidly growing field known as ‘online communities,’ as can be seen from the brief introduction to each that follows.

Fayard and DeSanctis use a qualitative approach to study developmental stages and the mechanisms that shaped and sustained an online forum (KMforum) for information systems professionals in India in their article Evolution of an Online Forum for Knowledge Management Professionals: A language Game Analysis . Their analysis shows how a loose collection of professionals with a common interest can develop a rhythm of conversation that allows the development of sustainable and meaningful online interaction, and reveals evolutionary dynamics in the life cycles of the forum suggestive of the developmental phases of offline groups. The article ends with useful suggestions about ways of improving community dynamics online.

Using longitudinal data, Kavanaugh, Carroll, Rosson, Zin, and Reese, in Community Networks: Where Offline Communities Meet Online , provide a deeper understanding of the use and social impact of a mature networked community, the Blacksburg Electronic Village (BEV). Their work investigated whether Internet-based technologies made a difference in the extent to which individuals become involved and participate in local social life. The analysis and discussion provided in this article of exogenous and mediating variables helps explain the relationship between community involvement and the use of the Internet to support the community. It appears from this study that education, extroversion, and age are significant variables for explaining people's involvement in this type of Internet communities.

Taking another approach, Laura Robinson examines the discussion produced in an online newspaper forum dedicated to the topic of the events of September 11th, 2001 in Brazil, France, and the United States in In Debating the Events of September 11th: Discursive and Interactional Dynamics in Three Online Fora . The study describes the ways in which interactional, social-behavioral, and semantic characteristics of each forum affected the simultaneous building of consensus and passionate conflict within each. One aspect of Robinson's findings is that regardless of the cultural environment, certain characteristics are associated with ideological divisiveness. In addition, cultural differences in interactional styles are carried from offline to the online environment, and affect the level of ideological antagonism expressed in each forum. These findings have special significance in the present global environment.

The work of Rodgers and Chen, Internet Community Group Participation: Psychosocial Benefits for Women with Breast Cancer , asserts that the needs of breast cancer patients and survivors are dynamic and change over time. This longitudinal study analyzed over 33,200 postings to a breast cancer bulletin board and 100 life stories of participants on the bulletin board to develop a profile of the women with breast cancer who were participating in the online support community. One important finding was a positive correlation between amount of participation in the group and psycho-social well-being over time. This has important implications for researchers and health care practitioners seeking ways to help those facing health challenges.

Much of the research on online patient support communities has addressed communities originating in the English-speaking Internet. In Evaluation of a Systematic Design for Virtual Patient Community , Leimeister and Krcmar describe an evaluation of the design elements of a virtual community for German cancer patients that was launched in 2001. In addition they examine design features that support trust development among participants, which they identify as an important contributor to the community's success. This study is an example of how design and evaluation can be tightly coupled as a community develops.

Turner, Smith, Fisher and Welser's work, Picturing Usenet: Mapping Computer-Mediated Collective Action , describes the vast and complex Usenet landscape through a variety of visual representations provided by Netscan, a tool designed for mining and visually representing relationships. Using this tool, the authors investigate how newsgroup hierarchies vary, how interaction within them varies and how participants' contributions vary by exploring large data sets of millions of entities. Netscan enables latent but invisible patterns in conversational data sets to become visible and provides a strong quantitative foundation for interpretive studies of patterns of communication on Usenet.

The article by Piller, Schubert, Koch, and Möslein, Overcoming Mass Confusion: Collaborative Customer Co-Design in Online Communities , seeks to transfer and apply current research on online communities to the manufacturing and mass customization arena. Their article describes an in-depth analysis of six case studies dealing with collaborative customer co-design projects in which mass confusion is an inherent problem. The study identifies sources of mass confusion and online community applications to help overcome these challenges. Three general solution paths are suggested: offering customers support to achieve their initial designs so that they can avoid having to struggle with starting from scratch; fostering joint creativity and problem-solving; and reducing the perception of risk by supporting trust.

The online panel, a type of organizational-sponsored virtual community, is the topic of Organizational Virtual Communities: Exploring Motivations Behind Online Panel Participation by Daugherty, Lee, Gangadharbatla, Kim, and Outhavong. Using Functional Theory as a framework for examining the complex way that attitudes function to influence motivation, this study seeks to determine if a person's attitudes toward joining an online panel varies by the functional source of their motivation and if their attitudes are based on a perceived sense of community stemming from their own membership.

Finally, in Using Social Psychology to Motivate Contributions to Online Communities , Ling, Beenen, Ludford, Wang, Chang, Li, Cosley, Frankowski, Terveen, Rashid, Resnick and Kraut designed and implemented a study to test design principles based upon social psychology theories. Their work points out that the fundamental challenge when using these theories to inform design is the differences in the goals and values of social psychologists and HCI/CSCW researchers. The authors demonstrate how mining social science theory can be used as a source of principles for design innovation and suggest that this is fertile ground for further research.

Our belief, having reviewed and selected articles for this special collection on online communities, is that the work represented reflects current research trends in this field reasonably well. Since research on online communities in the early 1990s, the research agenda has moved beyond characterizing participation of one or a few communities using a single medium such as Usenet or bulletin boards. The field is now much more diverse, and typically the communities being studied communicate via different modalities that include blending online and offline interaction. As in other maturing fields of study, there appears to be a progression from reporting on scattered, individual cases, through generalizing across examples, to applying and developing theories that explain what is observed. Research in online communities draws on methods, theories and practices from many disciplines, making this an exciting and challenging field.

We thank Heather Halpin from the College of Information Studies at the University of Maryland, who tracked the reviewing of the articles from submission of initial abstracts through to the final versions. We also thank Weimin Hou from the University of Maryland Baltimore County and the reviewers who provided the thoughtful comments that enabled us to select the best articles and supported the authors in improving their work.

Andrews , D. , Nonnecke , B. , & Preece , J. ( 2003 ). Electronic survey methodology: A case study in reaching hard to involve Internet users . International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction , 16 ( 2 ), 185 – 210 .

Google Scholar

Baym , N. ( 1993 ). Interpreting soap operas and creating community: Inside a computer–mediated fan culture . Journal of Folklore Research , 30 ( 2/3 ), 143 – 176 .

Baym , N. ( 2000 ). Tune, Log On: Soaps, fandom, and online community . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications .

Google Preview

De Souza , C. S. , & Preece , J. ( 2004 ). A framework for analyzing and understanding online communities . Interacting with Computers, The Interdisciplinary Journal of Human-Computer Interaction , 16 ( 3 ), 579 – 610 .

Gergen , K. ( 1997 ). Social saturation and the populated self . In G. E. Hawisher & C. L. Selfe (Eds.), Literacy, technology and society: Confronting the issues . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall .

Hamman , R. B. ( 1999 ). Computer networks linking network communities: Effects of AOL use upon pre-existing communities . Retrieved July 10, 2005 from http://www.socio.demon.co.uk/cybersociety/ .

Haythornthwaite , C. , & Wellman , B. ( 1998 ). Work, friendship, and media use for information exchange in a networked organization . Journal of the American Society for Information Science , 49 ( 12 ), 1101 – 1114 .

Herring , S. C. ( 1992, October ). Gender and participation in computer-mediated linguistic discourse . Washington, D.C.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics , document ED345552.

Herring , S. C. ( 2004 ). Computer-mediated discourse analysis: An approach to researching online behavior . In S. A. Barab , R. Kling , & J. H. Gray (Eds.), Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning (pp. 338 – 376 ). New York: Cambridge University Press .

Hiltz , S. R. ( 1985 ). Online Communities: A Case Study of the Office of the Future . Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corp .

Hine , C. ( 2000 ). Virtual Ethnography . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications .

Jones , Q. ( 1997 ). Virtual-communities, virtual-settlements and cyber-archaeology: A theoretical outline . Journal of Computer Mediated Communications , 3 ( 3 ). Retrieved July 10, 2005 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol3/issue3/jones.html .

Maloney-Krichmar , D. , & Preece , J. ( 2005 ). A multilevel analysis of sociability, usability and community dynamics in an online health community . Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction (special issue on Social Issues and HCI) , 12 ( 2 ), 201 – 232 .

Preece , J. ( 2000 ). Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability . Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons .

Rheingold , H. ( 1993 ). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier . Reading, MA: MIT Press .

Sack , W. ( 2000 ). Discourse diagrams: Interface design for very large-scale conversations . Proceedings of the 34th Hawaiian International Conference on System Sciences . Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer Society Press .

Viégas , F. B. , Wattenberg , M. , & Dave , K. ( 2004 ). Studying cooperation and conflict between authors with history flow visualizations . CHI 2004 , 575 – 582 .

Wellman , B. ( 1982 ). Studying personal communities . In P. Marsden & N. Lin (Eds.), Social Structure and Network Analysis (pp. 61 – 80 ). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage .

Wellman , B. ( 1997 ). An electronic group is virtually a social network . In S. Kiesler (Ed.). Culture of the Internet (pp. 179 – 205 ). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum .

Wellman , B. , & Gulia , M. ( 1999a ). Net Surfers don't ride alone: Virtual communities as communities . In B. Wellman (Ed.), Networks in the Global Village (pp. 331 – 366 ). Boulder, CO: Westview Press .

Wellman , B. , & Gulia , M. ( 1999b ). Virtual communities as communities: Net Surfers don't ride alone . In M. Smith & P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 163 – 190 ). Berkeley, CA: Routledge .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2017 | 1 |

| January 2018 | 73 |

| February 2018 | 548 |

| March 2018 | 713 |

| April 2018 | 771 |

| May 2018 | 913 |

| June 2018 | 450 |

| July 2018 | 376 |

| August 2018 | 649 |

| September 2018 | 745 |

| October 2018 | 952 |

| November 2018 | 1,135 |

| December 2018 | 708 |

| January 2019 | 716 |

| February 2019 | 806 |

| March 2019 | 686 |

| April 2019 | 703 |

| May 2019 | 613 |

| June 2019 | 506 |

| July 2019 | 415 |

| August 2019 | 442 |

| September 2019 | 481 |

| October 2019 | 599 |

| November 2019 | 463 |

| December 2019 | 316 |

| January 2020 | 346 |

| February 2020 | 328 |

| March 2020 | 321 |

| April 2020 | 459 |

| May 2020 | 240 |

| June 2020 | 282 |

| July 2020 | 191 |

| August 2020 | 206 |

| September 2020 | 322 |

| October 2020 | 310 |

| November 2020 | 259 |

| December 2020 | 269 |

| January 2021 | 315 |

| February 2021 | 353 |

| March 2021 | 381 |

| April 2021 | 330 |

| May 2021 | 444 |

| June 2021 | 216 |

| July 2021 | 215 |

| August 2021 | 276 |

| September 2021 | 298 |

| October 2021 | 233 |

| November 2021 | 213 |

| December 2021 | 186 |

| January 2022 | 208 |

| February 2022 | 222 |

| March 2022 | 298 |

| April 2022 | 282 |

| May 2022 | 258 |

| June 2022 | 223 |

| July 2022 | 168 |

| August 2022 | 137 |

| September 2022 | 221 |

| October 2022 | 234 |

| November 2022 | 186 |

| December 2022 | 176 |

| January 2023 | 189 |

| February 2023 | 210 |

| March 2023 | 286 |

| April 2023 | 248 |

| May 2023 | 267 |

| June 2023 | 198 |

| July 2023 | 224 |

| August 2023 | 189 |

| September 2023 | 209 |

| October 2023 | 222 |

| November 2023 | 186 |

| December 2023 | 195 |

| January 2024 | 191 |

| February 2024 | 200 |

| March 2024 | 230 |

| April 2024 | 298 |

| May 2024 | 279 |

| June 2024 | 237 |

| July 2024 | 197 |

| August 2024 | 247 |

| September 2024 | 103 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1083-6101

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Create Your Course

5 successful online community examples (+what makes them great), share this article.

For entrepreneurs and brands alike, online communities are a brilliant way to level up your business. Creating an online community gives you the chance to connect with your audience, increase engagement, and build better brand loyalty.

Skip ahead to see the top online community examples .

- Brand community example: Nia Technique

- Learning community example : Layla Martin

- Interest community example : Balanced Runner

- Fan community example : Bachelor Data

- Community of Action example : Earth Activist Training

Before you start creating an online community , it helps to know which types of online communities tend to be the most successful. Here are five types of online communities that might be a good fit, depending on your category of brand and audience.

5 types of successful online communities you need to know about

Online communities come in all shapes and sizes. You can shape your community depending on your aims, industry and how much input you want to have day-to-day. Take a look at these 5 types of online communities for ideas on all the different forms that online communities can take.

1. Brand communities

At the heart of any successful community is relationships. Brand communities are the ideal space for building a closer connection with your customers, while solidifying your authority in your industry. Use a brand community to encourage more engagement with your brand, including themed posts, competitions, and giveaways.

Brand communities put your brand front and center. This means they’re the ideal space for fostering brand loyalty among your customers and generating buzz.

2. Learning communities

If you’re a course creator or knowledge-based entrepreneur, learning communities can be a really valuable type of online community for your brand. Learning communities provide a space for supporting your customers through their learning journey and enhancing the learning experience.

In a learning community, you can share tips, resources, and research linked to your niche. Successful learning communities help to increase course completion rates and customer retention rates. They also connect learners to others in your academy, helping to make the learning process more dynamic, interactive, and fun.

Related: It’s Time to Tap Into Togetherness with Communities

3. Interest communities

Online communities built on a single hobby or passion are known as interest communities. This type of online community is ideal for entrepreneurs with a specialized brand linked to a topic that people are truly passionate about. (Even if that passion is as niche as something like chewing ice .)

Interest communities are all about engaging content that encourages people to connect over their interest. Asking open-ended questions, hosting live sessions, and running polls are all great forms of engagement for these types of communities.

4. Fan communities

A type of community that’s extra effective at encouraging engagement is fan communities. Fan communities center on one key theme, bringing enthusiasts together into one space. Most fan communities are built around celebrities, TV shows, books, artists, or other types of entertainment. If someone has a passion — you can create a fan community around it.

For brands, fan communities can be hugely effective for widening the scope of the parent brand and creating new opportunities for brand extensions. Think spin-off shows, fan merchandise, themed events, and more.

5. Communities of action

Unlike other types of online communities, communities of action have a strong mission statement that centers on making a difference. They provide a space for activists and experts to share knowledge, ideas, and events around a certain topic or cause. If your business has a social, political, or environmental focus — a community of action could be ideal for you.

Learn more about the different types of online communities and online community engagement ideas . Or read on for five extra successful online communities examples from entrepreneurs just like you.

5 successful online communities examples + tips on how to build your own

Ready to see some successful online communities in action? Here are five successful online communities examples to inspire you — including what they did well and tips you can use for building your own online community.

1. Brand community example: Nia Technique

Christina Wolf, founder and COO of Nia Technique , realized the value of building a community around her brand early on in her entrepreneurial journey with Thinkific. Communities offered the perfect opportunity to drive student engagement among learners in the Nia Technique mind-body fitness academy.

Here’s what Christina says:

Communities help our course participants stay connected with each other and their instructors in real time and build relationships with one another across the globe. These personal relationships help our students get more out of their online training experience and engage more deeply with our brand. I’m grateful for Thinkific’s ongoing commitment to listening to its course creators and making the Community experience even better with new features and benefits. CHRISTINA MAE WOLF, COO, NIA TECHNIQUE

Nia Technique uses online communities to keep the conversation going outside of her course academy. By introducing the community to new students as soon as they sign up for a course, Christina has successfully put the brand community at the heart of the learning experience.

How Nia Technique built their successful online community

Nia Technique uses a range of community engagement techniques to encourage more involvement in their online community. They’ve enlisted the help of their Nia Trainers to contribute to the community and act as community moderators.

This brand’s highly effective community engagement tactics include:

- Adding a “go to your community” call to action (CTA) in their student welcome email

- Encouraging new members to introduce themselves in the community

- Hosting live sessions for community members

- Creating a trainer guide with recommendations for how to post in the communities

➡️ Build explosive growth & revenue with community + 3 bonus cheat sheets

Want more business tips to unblock you? Sign up for the newsletter here.

Choosing the right platform

To build its successful online community, Nia Technique started out by using Facebook. Now, they’ve shifted their community to Thinkific’s Communities platform to bring course creation, course management, and their community all together into one place.

Choosing the right platform has been key for Nia Technique, helping them to:

- Simplify admin for the community

- Make it easier to connect trainers and students

- Help students who don’t have a Facebook account to connect with the community

Having transitioned their strong community off Facebook and onto Thinkific Communities, Christina and her team have now streamlined their community management, bringing everything together onto one integrated platform.

Key takeaways for this online community example

- Publicize your community: Encourage engagement with your online community from day one when students sign up for a course.

- Create clear community guidelines: Help students and trainers know what to post and how to post with a community guide.

- Thinkific Communities makes it simple: Bring your course content and community together for easier community management and admin.

2. Learning community example: Layla Martin

Layla Martin is an example of a brand that uses their community really creatively. This sexual wellness brand believes that their courses are about personal transformation and a strong community is crucial for helping to guide learners through the content and improve the learning journey.

The Layla Marin learning community is a supportive space that champions openness and reflection, offering students an extra level of insight into their own learning experience that they wouldn’t otherwise have. A learning community allows Layla Martin to offer students a holistic learning experience that encourages individual growth.

How Layla Martin built their successful online community

Everyone enrolled in a Layla Martin course is auto-enrolled in a community too. This means that every student feels a part of something bigger when they join the brand’s academy. Students are encouraged to engage with the community regularly and use it as part of their learning.

Layla Martin’s community managers encourage engagement through techniques including:

- Asking students to share their internal process as they progress through the course

- Encouraging feedback on the course content

- Getting students to describe course content in their own words

- Generating feedback and community learning opportunities

This strategy means that Layla Martin’s learning community is at the center of their academy, improving the experience for students and encouraging repeat customers.

Using creative community engagement techniques

Layla Martin used a range of community engagement techniques to build their online community in the early days. Here are some of the things that helped it become the community it is today:

- Always asking open-ended questions

- Starting discussions on controversial topics to generate more engagement

- Replying to any and all comments

- Producing clear community guidelines

- Not using the space for self-promotion

- Providing students with content that goes beyond the course

Creating a supportive environment

One of the things that makes this online community example successful is the support that students receive within the learning community. Layla Martin’s community is built on the belief that humans don’t like to be alone; we inherently search for like-minded people with similar goals and interests.

This plays out in their community strategy, including:

- Putting community front and center in the learning experience

- Encouraging learners to buy into each other’s personal transformations

- Using community discussions to inform and shape course content

Hot tip: Community conversations can influence your content strategy. The conversations within your community reveal the topics that interest learners and what they want to learn more about. Listen to this feedback and use it to shape your course content and community engagement.

- Make community part of the learning experience: Encourage students to post about their learning experience, apply what they’ve learnt, and ask for feedback from peers.

- Focus on your community ethos: Prioritize making your community a supportive, nurturing space that enhances student engagement with your course content.

- Listen to feedback: Pay attention to what your students are saying about your course content and what they’re discussing in your community to shape your content strategy.

3. Interest community example: Balanced Runner

Running expert Jae Gruenke is the entrepreneur behind Balanced Runner , a brand that helps runners relieve pain and improve their performance. Balanced Runner’s online community is extremely active thanks to Jae’s hands-on approach. This interest community brings together running enthusiasts in one place, with expert Jae at the center as the primary thought leader.

How Balanced Runner built their successful online community

When you’re first starting out with an online community, it can be tough to remember to stay active in the community space. Jae credits engagement routines with helping her grow her community and build a loyal following.

Engagement routines can include:

- Creating a plan for posting every day

- Setting aside at least 20 minutes per day for engagement

- Asking questions for your community to answer

- Sharing and reposting members’ content

It’s essential to make community engagement a habit when you’re first building your online community. This is especially important for solo entrepreneurs, who might not have a team of moderators on hand to help.

Active input from the face of the brand

Active engagement from your brand’s founder can also be critical for maintaining a healthy and thriving community. While some brands might be built on a topic or cause, some brands are centered on one individual. In these instances, your members want to hear from you.

The Balanced Runner is one example of this type of online community. Students’ brand loyalty is built on their love of the brand’s founder, Jae.

If this matches your business model, try these tips:

- Send personalized, thoughtful introduction emails to students

- Post consistently to encourage engagement

- Set monthly challenges for your members

- Share your experience, expertise, and stories in the community

- Offer one-to-one mentorship calls

- Set routines for regular engagement: When you’re starting out with your online community, set a routine for checking in with community members and responding to comments to make sure you’re active regularly.

- Give students what they want: Community moderators can be really helpful for day-to-day tasks, but if your students are eager to hear from the brand founder, make sure you build this into your community engagement strategy.

- Be encouraging: Remember that your members are real people. Make sure all engagement is encouraging, constructive and genuinely helpful to your students.

4. Fan community example: Bachelor Data

Suzana Somers built her wildly successful online community around one specific theme: the TV show The Bachelor. This niche allowed her to create a fan community that brought together lovers of The Bachelor and people with a strong interest in data analysis. Starting with a successful online community, Suzana was then able to monetize her brand and create her Bachelor Data course academy with Thinkific.

How Bachelor Data built their successful online community

If you’re starting a fan community to compliment your brand, you need to put your fans first. Follow what they’re talking about, what they’re sharing, and the questions that are creating a stir as a way to build your community.

Here are some of the ways that Bachelor Data used this method to grow:

- Using visually-interesting, shareable content to increase engagement

- Asking audiences what they want to learn more about

- Getting direct feedback from learners on course content

For any online community, success lies in your ability to give your customers and members what they want — whether that’s themes, types of content, challenges, or anything else. When it comes to fan communities, this is especially important.

Engaging with current events and issues

A key aspect of the Bachelor Data business model that allowed them to grow was their engagement with current events and issues. Bachelor Data used their platform to comment on diversity, inclusion, and representation in The Bachelor and across wider popular culture.

Using current events to shape your community engagement can include:

- Asking community questions about trending topics in the news

- Engaging with publications, podcasters, and brands on key issues

- Inviting guest speakers to weigh in on debates

By encouraging respectful debate and engagement around current issues, you can drive engagement in your community and make your brand more relevant. Stay flexible and keep your ear to the ground so you can keep up-to-date with key discussions surrounding your industry.

- Make content visual: Photos, graphics, and video tend to get more engagement on social media than other types of content. Use this to your advantage when creating content for your community.

- Have a flexible engagement strategy: Respond to the interests of your community members and current events when shaping your community strategy to drive engagement.

- Don’t overthink it: Building a successful online community doesn’t have to be difficult — if you can keep your community members front and center in everything you do, you can grow your online community organically.

Learn more about how Bachelor Data started a successful online course business from scratch with this full case study .

5. Community of Action example: Earth Activist Training

A community-focused brand, Earth Activist Training built its online community around activism and environmentalism. Founded by business partners Starhawk and Penny Livingston-Stark, the academy teaches permaculture design grounded in spirituality. Today, they have over 1,500 enrollees and a hugely successful and committed online community.

How Earth Activist Training built their successful online community

Depending on your industry, a community of action can be a great way to bring customers together around a common cause. Earth Activist Training grew their online community with a focus on organizing around climate change, anti-racism, and social justice, as well as environmental issues.

Here are some of the ways they built their community of action:

- Creating a clear mission statement

- Publicizing their community values and aims

- Collaborating with experts in their niche

These methods help Earth Activist Training create a community built on collective goals, helping members to learn more about topics, ask questions, and engage with activist opportunities.

Using community for live learning opportunities

Where Earth Activist Training have really excelled in building their online community is through their use of live learning opportunities. As their academy is focused on a very practical topic — permaculture design — it is really suited to live learning.

The brand uses live learning to encourage more engagement in their community, hook new learners, and bring knowledge and opportunities to existing community members. This adds genuine value to their community offering, giving people a reason to stick around.

Earth Activist Training use a range of live learning methods including:

- Hosting live events with guest speakers

- Offering free how-to classes and live tutorials

- Setting regular Zoom meetings with community members

Live learning is integral to the Earth Activist Training online community and they provide the brand with the opportunity to bring course content, live training, and live spiritual rituals closer to their community members.

- Create a mission statement: To help unite your community members around a common goal, write a mission statement to clarify your aims and expectations for your online community.

- Offer live learning opportunities: If your niche or industry is especially suited to live sessions, consider hosting live events as a method to engage community members.

- Collaborate with experts: Add extra value to your community by inviting guests to contribute to your community, including live events, tutorials and Ask-Me-Anything sessions.

Read More: Learn about Thinkific Communities features here.

Use these successful online communities examples to inspire your own brand community

If you’re building a brand, it’s a good idea to start thinking about your online community now. An online community is a hugely effective way to boost customer loyalty and get more people talking about your brand and engaging with it.

Use these successful online communities examples to inspire you and help you shape your own community. While every community is different, these examples can give you the push you need to get started.

To build your own online community, sign up for Thinkific today to start using Thinkific Communities.

Allie is a Product Marketer at Thinkific focussed on building and launching solutions that help creators expand and scale their business through online learning products.

- 11 Best Community Management Courses

- How To Craft Magnetic & Compelling Learning Outcomes

- Essential Questions To Ask In Your Training Evaluation Survey

- Best Equipment & Software For Creating Online Courses

- How to Create a Compelling Sales Page for Your Online Course

Related Articles

14 icebreaker games to start your virtual meetings off right.

Online meetings don’t have to be awkward. These 14 ideas for icebreaker games will help you keep your team engaged and entertained.

Podcasting & Online Course Creation (Daniel J Lewis Interview)

Thinkific Teach Online TV interview with podcasting expert Daniel J Lewis on the similarities between podcasting and online course creation.

Pricing Workshops: Navigating the Balance Between Value and Cost

Confused about pricing your training workshop? Discover the strategies behind setting the right price for your workshop. Explore what workshop facilitators charge and make informed pricing decisions.

Try Thinkific for yourself!

Accomplish your course creation and student success goals faster with thinkific..

Download this guide and start building your online program!

It is on its way to your inbox

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Online communities

- Technology and analytics

- Web-based technologies

- Internet of Things

- Social media

Can Absence Make a Team Grow Stronger?

- Ann Majchrzak

- Arvind Malhotra

- Jeffrey Stamps

- Jessica Lipnack

- From the May 2004 Issue

When CEOs Engage Directly with Customers

- G M Tomas Hult

- November 22, 2022

Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier

- Etienne Wenger

- William M. Snyder

- From the January–February 2000 Issue

Threads Foreshadows a Big - and Surprising - Shift in Social Media

- Scott Duke Kominers

- July 13, 2023

Platforms Need to Work with Their Users – Not Against Them

- Ethan Bueno de Mesquita

- Andrew Hall

- May 04, 2022

Future Space: A New Blueprint for Business Architecture

- Jeffrey Huang

- From the April 2001 Issue

Cautionary Tales from Cryptoland

- Thomas Stackpole

- May 10, 2022

Making Sense of the NFT Marketplace

- Pavel Kireyev

- Peter C. Evans

- November 18, 2021

The CEO of Roblox on Scaling Community-Sourced Innovation

- David Baszucki

- From the March–April 2022 Issue

Research: How People Feel About Paying for Social Media

- Forrest V Morgeson

- April 05, 2023

Alternative Workplace: Changing Where and How People Work

- Mahlon Apgar

- From the May–June 1998 Issue

8 Best Practices for Creating a Compelling Customer Experience

- March 14, 2023

How Luxury Brands Are Manufacturing Scarcity in the Digital Economy

- Hannes Gurzki

- January 28, 2022

The Rebirth of Software as a Service

- Frank V. Cespedes

- Jacco van der Kooij

- April 18, 2023

Reverse Product Placement in Virtual Worlds

- David Edery

- From the December 2006 Issue

Do Customer Communities Pay Off?

- Rene Algesheimer

- Paul M. Dholakia

- From the November 2006 Issue

Should You Start a Generative AI Company?

- Julian De Freitas

- June 19, 2023

Are You Ready for E-tailing 2.0?

- From the October 2006 Issue

Innovating in Uncertain Times: Lessons from 2022

- Chris Howard

- December 20, 2022

Power to the People

- Nirav Tolia

- Bronwyn Fryer

- From the January 2001 Issue

TikTok in 2020: Super App or Supernova?

- Jeffrey Rayport

- Dan O'Brien

- February 19, 2021

E-Commerce Analytics for CPG Firms (B): Optimizing Assortment for a New Retailer

- Ayelet Israeli

- Fedor Ted Lisitsyn

- January 06, 2021

Linux in 2004

- Pankaj Ghemawat

- Brian Subirana

- Christina Pham

- July 14, 2004

Social Strategy at Nike

- Mikolaj Jan Piskorski

- Ryan Johnson

- April 17, 2012

Mavens & Moguls: Creating a New Business Model

- Myra M. Hart

- Kristin J. Lieb

- Victoria W. Winston

- October 29, 2004

Work from Anywhere: The HBR Guides Collection (5 Books)

- Harvard Business Review

- June 13, 2023

Collaborative Filtering, Technology Note

- Erik Brynjolfsson

- Jean-Claude Charlet

- March 01, 1998

Arcelik: From a Dealer Network to an Omnichannel Experience

- Fares Khrais

Magic: the Gathering - Harnessing an Engaged Player Community

- Edward Boon

- Philip Grant

- Ezequiel Reficco

- May 02, 2017

(Water) Public-Private Partnerships: The Economics

- Peter Debaere

- Andrew Kapral

- December 13, 2020

eGrocery and the Role of Data for CPG Firms

- Mark A. Irwin

- February 01, 2021

CashDrop (A)

- Rembrand Koning

- Paul A. Gompers

- Sarah Gulick

- March 19, 2021

Arcelik: COVID-19 Fueled Omnichannel Growth (B)

- February 04, 2021

Valuing Snap After the IPO Quiet Period (A)

- Marco Di Maggio

- Benjamin C. Esty

- Greg Saldutte

- June 05, 2018

Breastcancer.org: Fundraising Challenges of a Social Enterprise in a Crowded Market

- Sheri Lambert

- Sara Honovich

- February 15, 2022

Managing Teams in the Hybrid Age: The HBR Guides Collection (8 Books)

Online auction markets.

- Pai-Ling Yin

- August 23, 2004

Virtual Reality and the Gaming Sector 2017

- David B. Yoffie

- Natalia Prieto Nino

- Prasad Raman

- Brad Kowalk

- Ruby Tamberino

- September 19, 2017

1923: Hyperinflation in Germany

- Robert F. Bruner

- Christopher De Notto

- December 17, 2020

BeM: A Start-Up's Journey through Online Product Reviews

- Leandro Guissoni

- Thales S. Teixeira

- Ruth Costas

- April 15, 2024

Popular Topics

Partner center.

What motivates online community contributors to contribute consistently? A case study on Stackoverflow netizens

- Published: 25 June 2022

- Volume 42 , pages 10468–10481, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Sohaib Mustafa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8070-976X 1 ,

- Wen Zhang 1 &

- Muhammad Mateen Naveed 1

4345 Accesses

29 Citations

Explore all metrics

Online Question and answer (Q&A) communities are the common and famous platforms to learn and share knowledge and are very useful for every knowledge seeker. Less knowledge contribution is a critical issue for the sustainability and future of these platforms. The motivation of inactive users to participate in Q&A communities is a real challenge. Based on the social cognitive and social exchange theory, we have studied the knowledge contribution patterns of active and consistent StackOverflow users over the last eleven years. We have used a difference generalized method of moments estimator to estimate the proposed model. Results revealed that reciprocation of knowledge and social interaction positively, whereas knowledge seeking of active and consistent users negatively influences knowledge contribution. Peer recognition and repudiation have partially positive and negative effects on users’ knowledge contribution. This research offers theoretical and practical suggestions to encourage people to contribute their knowledge to online Q&A communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Online Knowledge-Sharing Motivators of Top Contributors in 30 Q&A Sites

Harnessing Engagement for Knowledge Creation Acceleration in Collaborative Q&A Systems

Users roles identification on online crowdsourced Q&A platforms and encyclopedias: a survey

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Online Question and answer communities (Q&A) are unanimously gaining popularity in all fields of life. A common person can solve problems, acquire knowledge, share ideas, and express their feelings or experience about some place or thing. Particularly these communities help those looking for the answers to their technical queries and seek guidance in their practical workplace.

Q&A communities have become popular in the workplace because of their ease of use and speed of response. The modern age of technology has reshaped and restructured how people study and share information. Meaningfully, the COVID-19 epidemic reaffirmed the value of Q&A communities by significantly increasing the need for online knowledge exchange (Vaughan, 2020 ). Online resources make it possible for anybody, at any time, to find information on almost any topic. A broad spectrum of people, from beginners to experts, may benefit from internet resources, which provide a vast range of information in simple and understandable terms. Q&A sharing websites like Stack Overflow, Quora, Ask Ubuntu, SuperUser, and Yahoo! Answer are examples of commonly used Q&A communities.

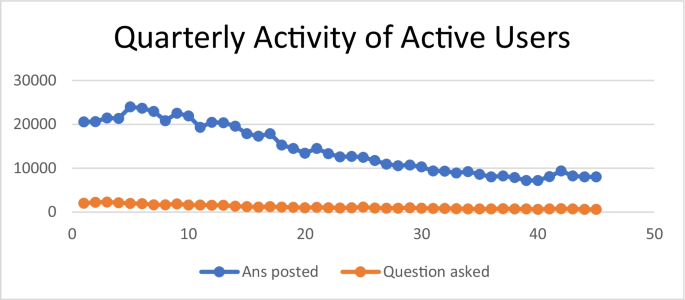

An online Q&A community’s users are vital components, and their active engagement is essential to the community’s growth and development. Apart from the benefits and low cost of acquiring knowledge, these communities face a severe issue of low participation. Users of these communities acquire knowledge and hesitate to contribute knowledge. A decreasing trend in knowledge sharing has also been observed among the most active users of Stackoverflow (Graph 1 ). It reflects that over some time, knowledge contribution decrease. As a result, many Q&A groups are grappling with the issue of how to encourage members to keep contributing to the body of knowledge (Chen et al., 2021 ; Dong et al., 2020 ). To determine what elements influence users’ willingness to engage in community activities, particularly knowledge contribution, it is necessary to identify these factors (Guan et al., 2018 . Understanding the strategies that keep participants engaged and address the wide range of motives across time and participant types is helpful in stimulating inactive users.

Questions and answers contributed

To remain operational, Q&A websites must rely on the continual voluntary contribution of their users when all users do not contribute adequately to online knowledge-sharing communities, particularly those focused on practical knowledge structure and distribution in the technical background. The ability of these communities to survive can be jeopardized. The phrase “tragedy of the commons,“ coined by (Hardin, 1968 ), describes the situation in online knowledge-sharing groups. According to this concept, many users choose to take a free journey or contribute insufficiently rather than consistently participating in an online knowledge-sharing community that is open and freely accessible to anybody.

StackOverflow is one of the leading Q&A communities that serve sixteen million Footnote 1 registered users to search for knowledge and provide an opportunity to contribute their knowledge. It has gained widespread popularity among enthusiast programmers and professionals since its launch in 2008. Stackoverflow data for 2020 revealed that only 6.07% of users actively participate 1 at StackOverflow, even though most community members are inactive yet offer some knowledge.

Previous studies have identified that knowledge-seeking has a positive (Chen et al., 2021 ; Guan et al., 2018 ) or no impact (Chen et al., 2019 ; Wang et al., 2022 ) on knowledge sharing. Self-interest and prosocial motivation have also significantly affected continuous knowledge contribution (Dong et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, peer repudiation has a negative (Wang et al., 2022 ) or positive (Chen et al., 2019 ) impact on knowledge sharing. Hence, it needs to be further explored to understand the contribution of these factors toward users’ knowledge sharing.

Researchers have rarely investigated the subject to our knowledge that thoroughly investigated the knowledge sharing behaviour of consistent and active users for a long period and applied its results to solve the issue of low user participation. Hence the following research question is presented to study.

RQ. What motivates online community users to contribute consistently ?

There is an essential need to investigate the motivational factors behind the continuous participation of users and replicate the same for the rest of the community members to enhance their participation. For this purpose, we have selected StackOverflow and picked users who participated at least quarterly and asked a question, answered a question, or posed a comment once quarterly. We have tracked the activities of these pioneer users from 2010 to 2020 and applied the generalized method of moments (GMM) panel data model to check the impact of their different activities on their knowledge contribution. The study results can solve the most important practical problem of less contribution by considering the influential factors and their effect on users’ knowledge contribution. Results revealed that knowledge-seeking as a question posted, peer recognition as upvotes, and peer repudiation as peeve votes negatively influence active users of StackOverflow to share knowledge. Whereas reciprocation as answer received, social interaction as comment received, peer precogitation as favourite votes, and peer repudiation as downvotes positively influence active users to contribute knowledge.

Theoretical foundation

There are two commonly known and recognized ways of knowledge sharing, face to face and online. Face-to-face knowledge sharing usually requires the physical presence of participants at the time of knowledge sharing. In contrast, the latter does not need a physical presence at the same time to interact. Virtual interaction is enough in online knowledge sharing. The process of managing knowledge includes the sharing of existing knowledge. The act of exchanging one’s knowledge (skills, information, or expertise) with other individuals, whether they are family members, classmates, friends, members of a community (such as Stackoverflow), or members of the same or other organizations, is an activity known as “knowledge sharing” (Serban & Luan, 2002 ). It creates a bridge between individual and corporate knowledge, which boosts absorptive and innovative ability and ultimately results in a sustainable competitive advantage for both people and businesses (Dalkir, 2013 ).

There are increasing practical and academic issues for the majority of online Q&A communities as a result of the declining interaction and information sharing. As a result, previous research on internet knowledge sharing has focused on the social strategies that encourage involvement in online communities and information sharing. Many academics have frequently established the theoretical foundation to explain the knowledge contribution and users’ participation in online Q&A communities using social cognitive and social exchange theories. These theories help underlie the theoretical foundation to investigate and explore the factors behind users’ continuous participation.

Social cognitive theory

Miller and Dollard ( 1941 ) social learning theory believes that witnessing how others behave in social situations may impact one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Social cognitive theory (SCT), which is derived from social learning theory, uses a triadic reciprocal model to describe human behaviour where environment, personal characteristics (such as cognition), and actions all interact with one other to explain human behaviour (Bandura, 1986 ). Based on this theory, learning may be seen as information processing in which past experiences and environmental cues function as expressions and guide future action. Gaining social recognition is a key driver of knowledge sharing in online Q&A groups because user connections are mostly weak linkages to gain meaningful information. As a result, the participants may learn from the feedback they get from society about the relevance of certain participation behaviours and may further change their subsequent participation practices to respond to the general demand (Shi et al., 2021 ). SCT shows that people practice actions similar to those rewarded because they believe they will lead to a favourable result (Bandura, 1986 ).

Similarly, in online Q&A groups, we regard the responses that get the most votes as modelled answers. We’d look at how these responses function as precursors to community contributions to knowledge. We interpret community feedback as a set of behaviour outcomes that serve as an encouragement (social reward, as indicated by SCT) to encourage participants to execute what they have learned through previous experience or see others perform what they have contributed and learned. In the context of social cognition theory, self-efficacy and outcome expectancies are two essential variables that relate to an individual’s confidence in his capacity to effectively conduct action and the chance that an individual’s activity may lead to a given result, respectively (Anderson et al., 2007 ). Prior studies also explained that group size, social learning, and peer recognition impact users’ knowledge contribution (Jin et al., 2015 ). As a result, earlier online Q&A community contributions might influence future contributions. Affective and vicarious learning is used in SCT to examine the influence of earlier actions on future knowledge contributing behaviours.

Social exchange theory

Information sharing is a social interaction emphasized by economic exchange theory (Liu et al., 2005 ). Extrinsic incentives focus on the economic exchange theory, while intrinsic rewards focus on the social exchange theory. An individual’s actions are influenced by the outcomes of his analysis of the advantages and sacrifices he receives and makes when he engages in a certain activity. As long as the advantages outweigh the costs, people are more likely to act. Previous research has shown a link between good corporate knowledge management and incentive systems. Extrinsic motivations, such as money or promotion prospects, encourage employees to share their expertise to gain an advantage in the workplace (Gee & Young-Gul, 2002 ). Unspecified commitments that cannot be defined as a tangible medium of exchange are the main focus of social exchanges. In online Q&A communities, intrinsic rewards are common instead of extrinsic ones, and participants reciprocate their knowledge when they receive sufficient intrinsic rewards. As a result, social transaction tends to foster sentiments of belonging, personal duty, appreciation, trust, and loyalty (Jin et al., 2015 ). When it comes to online social Q&A groups, knowledge and attention are two of the most common exchangeable products. In online social media, attention has become a rare commodity. Thus those who give information expect to get knowledge or attention as compensation (Jin et al., 2015 ). Hence social exchange theory is used to understand the knowledge exchange of participants in the context of their group interaction.

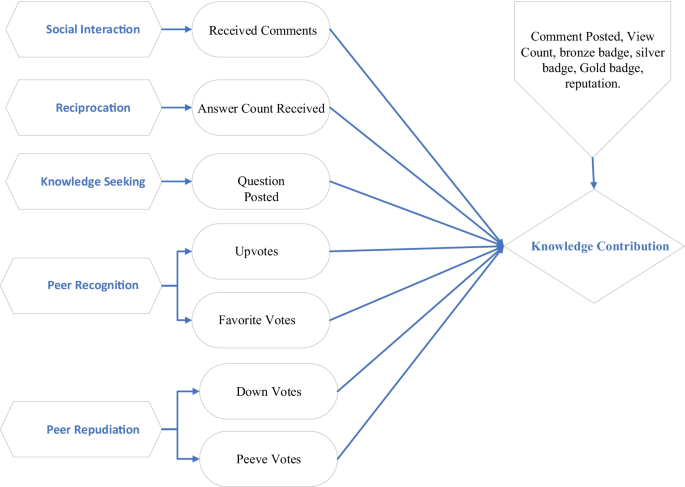

Research model & hypothesis development

We establish a research model to guide our academic inquiry into the relationship between motivating elements on Q&A websites and user knowledge engagement with the theoretical backdrop stated previously. The following is a suggested study framework that incorporates user-generated questions, commenting, and voting procedures to shed light on the diversity in each user’s internet-based knowledge sharing behaviour (Fig. 1 ). For example, it is anticipated that the incentive elements supplied by a single user’s Question, response, upvoting, and favourite votes all contribute to knowledge sharing. In contrast, it is believed that peeve voting and downvoting are inversely related to knowledge contribution. Fellow users provide feedback since it is predicted that internet-based communication promotes individual knowledge exchange.

Conceptual framework

Commenting effect on knowledge contribution

Public cooperation in the form of comments amongst online colleagues is a critical component of the success of an internet-based platform. The distinction between commenting and voting is interconnected; the former serves as a communication and collaborative problem-solving route, while the latter serves as a mechanism for collaborative motivation or demotivation to stimulate actions. The internet-based social platform’s reward and reputation algorithmic mechanism facilitates this. It’s well accepted that the individual psyche may have a beneficial or detrimental impact on an individual’s self-worth, capacity to communicate successfully with others, and ability to prosper in a work environment (Wiegand & Geller, 2005 ; Guan et al., 2018 ) found that online users’ knowledge contribution is favourably influenced by social feedback. Chen ( 2019 ) argues that the conversation about the authenticity and reliability of contributed knowledge moulds users’ perception and, ultimately, their motivation for committed contribution in an internet-based context. They also discovered that favourable remarks motivate knowledge contributors to do their best work. According to current research, community interaction strongly motivates participants to participate in web knowledge-sharing networks (Chang & Chuang, 2011 ). However, researchers still need to fully investigate the role of comments in encouraging involvement in an online system. This study exclusively investigates the comments received by users and their impact on the knowledge contribution of active users in StackOverflow. The number of comments received might indicate how connected users are to the community and how frequently they collaborate with peers on a web-based knowledge-sharing platform. As much as a user gets comments from other community members, it demonstrates that s/he is becoming more engaged with the community and interested in addressing issues (Tajfel & Turner, 1986 ; Burke et al., 2009 ) found that new users who received a reaction from their peers encouraged them to contribute to a web-based news platform. Through social interaction, peers may support and appreciate one other’s accomplishments or criticize the irrelevant and low-quality knowledge contributed to the community (Liao et al., 2020 ). With this discussion, we hypothesize that.

H1: Peer comments influence active users’ knowledge contribution.

Effect of a question asked on knowledge contribution