Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Covid 19 — My Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

My Experience During The Covid-19 Pandemic

- Categories: Covid 19

About this sample

Words: 440 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 440 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, physical impact, mental and emotional impact, social impact.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Mental health and COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/apa-blog/2020/03/mental-health-and-covid-19

- The New York Times. (2020). Coping with Coronavirus Anxiety. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/well/family/coronavirus-anxiety-mental-health.html

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1104 words

3 pages / 1477 words

2 pages / 876 words

2 pages / 985 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Covid 19

The COVID-19 pandemic, which first emerged in late 2019, has brought about a global crisis that extends far beyond the realms of physical health. Beyond the direct threat to one's physical well-being, the pandemic has unleashed [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented global crisis, has left an indelible mark on individuals' lives, including its profound effects on mental health. This essay, titled "How Did the Pandemic Affect My Mental Health," [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the indispensable role of accurate information and scientific advancements in managing public health crises. In a time marked by uncertainty and fear, access to reliable data and ongoing [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had far-reaching consequences on individuals' lives worldwide. This essay will explore the personal impacts of the pandemic, focusing on mental and emotional [...]

As a Computer Science student who never took Pre-Calculus and Basic Calculus in Senior High School, I never realized that there will be a relevance of Calculus in everyday life for a student. Before the beginning of it uses, [...]

Good morning, today I am going to give a speech on something that is hot in the news at the moment and could potentially harm us, that thing is a coronavirus. There isn’t a huge amount to say about it as it is still being [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

- Recommendations

Most Popular

- Is Kamala Harris beating Donald Trump in the polls?

- What caused the global stock market meltdown

- What happens when everyone decides they need a gun?

- Bangladesh’s prime minister just fled the country in a helicopter. Why?

- The misleading controversy over an Olympic women’s boxing match, briefly explained

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Music production is getting easier. Does that make it better?

Just as the US team enters its influencer era, the sport is in trouble.

Conservatives are capitalizing on the abandoned Khelif-Carini fight to levy anti-trans attacks.

An exhausting — if not exhaustive — timeline of J.K. Rowling’s transphobia.

Forget the medals — these athletes won the internet’s love.

Caroline Gleich’s Utah Senate campaign is a sign of the blurring lines between digital creators and politicians.

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The 50 Best Romance Novels to Read Right Now

- Mark Kelly and the History of Astronauts Making the Jump to Politics

- The Young Women Challenging Iran’s Regime

- How to Be More Spontaneous As a Busy Adult

- Can Food Really Change Your Hormones?

- Column: Why Watching Simone Biles Makes Me Cry

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at [email protected]

COVID-19 reflections: the lessons learnt from the pandemic

by Alana Cullen , Lucy Lipscombe 03 February 2021

Imperial researchers reflect on the lessons they will take away from the pandemic.

Over the past 12 months the Imperial College London community has devoted an intense amount of time and research to COVID-19. Members of the community have been making fundamental scientific contributions to respond to coronavirus , from advising government policy to critical therapy research. A year on, Imperial researchers reflect on what lasting impact the pandemic has left on them.

Watch the clip above to hear the researchers’ insights.

A global contributor

Before I felt like just a person in the world, and now I feel like I’m one of those important people in the world! Dr Kai Hu

The first lesson is how fast- moving science is at this time. It is exciting to have been “on the forefront of vaccine discoveries” said Dr Anna Blakney, Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia, formally a Research Fellow in Imperial’s Department of Infection and Immunity . Imperial has also been key in finding optimal treatments for COVID-19, with clinical academics such as Anthony Gordon , Professor of Anaesthesia and Critical Care and Intensive Care consultant, caring for critically ill patients in intensive care units as well as leading clinical trials. Findings from these trials include the effective use of an arthritis drug in reducing mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The science doesn’t stop there. Outside of the lab Imperial academics have been informing UK government policy. Since the emergence of coronavirus the team from the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis and Jameel Institute (J-IDEA) at Imperial have been predicting the course of the pandemic and informing policy. The team have also been supporting the COVID-19 response in New York State. Furthermore, Imperial academics including Professor Charles Bangham and Professor Wendy Barclay continue to advise the government as part of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE).

In total the Imperial community has contributed nearly 2,000 key workers to essential services and research, from biomedical engineers developing rapid COVID-19 tests to health economists, generating a wealth of knowledge about the science behind the pandemic.

“This is the first time where I feel like what I have learnt is very useful” said Dr Kai Hu, Research Associate in the Department of Infectious Disease. “Before I felt like just a person in the world, and now I feel like I’m one of those important people in the world.” Dr Kai Hu is part of Professor Robin Shattock’s COVID-19 vaccine team, who continue to develop an RNA vaccine .

Watch our full COVID reflections video below, including researchers sharing their hopes for the future.

Collaboration is key

Another key lesson learnt is how much stronger we are when we work together. Vaccine development, production and delivery have all been achieved in under 12 months – an unprecedented timeframe for any disease prevention tool. This goes to show that collaborative efforts with the right funding will go a long way in biomedical science. “I can work even harder than I thought I could work because we can come together as a team” says Dr Paul McKay , Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Infectious Disease. “Science is a competitive endeavour, but a collaborative endeavour too.”

Something that will leave a lasting impression is the kindness of community, family and friends. Kindness at this time has been “unparalleled” said Sonia Saxena , Professor of Primary Care and General Practitioner. From providing free meals to NHS workers to educational materials for homeschooling there has been a feeling of togetherness, even when apart, throughout these difficult times. Going forward, we can bring these lessons into science, bringing more collaboration and kindness into the everyday.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Alana Cullen Communications Division

Contact details

Email: [email protected] Show all stories by this author

Lucy Lipscombe Communications Division

Strategy-staff-community , Vaccines , Infectious-diseases , Viruses , JIDEA , Coronavirus , Staff-development , COVIDWEF , Public-health See more tags

Leave a comment

Your comment may be published, displaying your name as you provide it, unless you request otherwise. Your contact details will never be published.

Latest news

Badger boost

Farmer-led badger vaccination could revolutionise mission to tackle bovine tb, news in brief, animal research and ai/bmi health predictors: news from imperial, singapore startups, imperial’s ai startups showcase ideas in singapore, most popular.

1 Infection study:

Covid-19 – how long am i infectious and when can i safely leave isolation, 2 alzheimer's disease:, weight-loss drug may slow alzheimer’s decline, 3 psychedelic treatment:, magic mushroom compound increases brain connectivity in people with depression, 4 psychedelic experience:, advanced brain imaging study hints at how dmt alters perception of reality, latest comments, comment on scientists confirm the universe has no direction: it is like moving in a car... we are measuring the movement of one passenger to another, that remai…, comment on climate risks from exceeding 1.5°c reduced if warming swiftly reversed: the only possible way to prevent prolonged overshoot in the near term is sunlight reflection or "sol…, comment on professor david q mayne freng frs 1930 - 2024 : david mayne has been a constant - and extremely benevolent - presence in my life for several decades…, latest tweets.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Reflections On Coronavirus A Year In

Madeline K. Sofia

Rebecca Ramirez

Emily Kwong

An elderly couple wearing face masks walks in Madrid on April 30, 2020 during a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 disease. Gabriel Bouys/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

An elderly couple wearing face masks walks in Madrid on April 30, 2020 during a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 disease.

It's been about a year since the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic. The world has learned a lot in that time — about how the virus spreads, who is at heightened risk and how the disease progresses. Today, Maddie walks us through some of these big lessons.

Follow NPR's continued coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

Helpful links from the episode:

- How To Protect Yourself From Aerosol Transmission

- Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity

- The Key To Coronavirus Testing Is Community

Reach the show by emailing [email protected] .

This episode was produced by Rebecca Ramirez, edited by Gisele Grayson, and fact-checked by Rasha Aridi. Stacey Abbott was the audio engineer. Special thanks to Ariela Zebede and Leah Donella.

COVID-19: A year in reflections

As we mark a full year since the global pandemic upended all of our lives, we asked members of the UC community to share their reflections on how these past months have changed them, and what will stay with them about this unprecedented time in the years to come.

The picture that emerges is one of hardship, courage, gratitude and resilience. For many of us, the last 12 months have meant long hours and rising to meet new challenges with our teammates, families, communities and bubbles. We helped support others in their grief and were helped by others when grief came home to us. We found new strengths in loneliness and formed new practices and bonds to ward off despair.

Now, as we begin to see a little light at the end of the tunnel, here in their own voices, members of UC’s community look back on a year like no other.

On never falling off the treadmill

In the early days of 2020, two doctors, Daniel Uslan and Annabelle de St. Maurice , had already begun preparations with their colleagues in the command center at UCLA Health for the looming pandemic. As clinical chief of infectious diseases and co-chief infection prevention officer at UCLA Health, Dr. Uslan was working alongside Dr. de St. Maurice, pediatric infection control lead and co-chief infection prevention officer, nearly every waking moment. Their work spanned planning for patients, emergency preparedness, communications, and more.

“By the time California shut down non-essential businesses, I had already been working on COVID-19 for several weeks and my day-to-day life had already been thrown into chaos. In the early days I hoped, perhaps naively, that we would all hunker down for a few months and then the crisis would pass us by.”

As more information became available, that hope dimmed.

Dr. Tisha Wang put her entire life on hold when the pandemic hit — as the person overseeing pulmonary and critical care faculty and trainees for UCLA Health, she had no other option. It was clear, early on, that protecting health care workers from infection would be absolutely vital for saving the lives of the critically ill patients showing up at the hospital.

She describes those last three weeks of March 2020 as the worst three weeks of her career. Protecting the workforce, so they could protect the critically ill, was a heavy burden to carry. And as we know, that burden was carried for far longer than those three weeks (Dr. Wang speaks about the difficult experiences of saying goodbye to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, here ). Dr. Wang:

“We wondered if it was ever going to end — the deaths, the grieving, the suffering, the stress and anxiety compounded by the social isolation. In our minds, how could this possibly go on for months to years? I felt like I was constantly running on a treadmill and close to running out of steam. To my disbelief, after 9 months of running, the speed of the treadmill was turned up by 50 percent when Los Angeles became the epicenter of the pandemic. I had no choice but to keep running, but was I going to fall off?

“What have I learned? This is actually a team-based marathon. I was never going to fall off of that treadmill. Someone was going to come along and tag me out and let me breathe and rest for a moment. And as soon as I got some water and air, I was going to jump back on and do the same for them.”

Now there is time, and hope, we can address this situation better in the future. Dr. de St. Maurice has begun to reflect:

“The pandemic has taught us many lessons about preparedness and health equity, among other things. What can we do better in the future to prevent pandemics like this from occurring? What modifications have we made in our lives as a result of the pandemic that are positive and how can we continue these in the future? What health care inequities have intensified as a result of the pandemic and how can we work to improve those inequities?

“In the past many physicians and health care workers would work when they weren’t feeling well and I think that will change going forward.”

On living in a bubble year

Steven Pease has been working part-time at home in his capacity in IT asset management, in a bubble with his wife, their children and her parents, one of whom, her father, passed just before turning 100 in October. Planning the funeral and sharing mourning in the pandemic was challenging, an experience shared by many. Still, Pease felt gratitude for his connection to his family.

“To be certain, some of this will go down in our collective memories as the worst of times. That said, to have been locked up in our little ‘bubble’ together; forced to navigate together uncertain and new waters, but to get to do so with someone I love was in some ways very, very special. I believe that someday I'll look back on this time and see it as some of the best.”

Valerie Simmermaker has been working remotely for the UCPath Center near Riverside and finding silver linings in the pandemic as a single mom.

“I would say for us the stay at home order — working and schooling from home has ultimately been really good for us. I have always been a single parent and my children were used to coming home from school alone, and helping with chores and cooking, sometimes even doing grocery shopping while I worked. This has allowed us to really bond, I am finally able to help them with school work and we eat dinner before 7 p.m., we have really gotten close during this time together.”

Darlene Alvarez at the UC Retirement Administration Service Center (RASC) has had similar experiences with her children, trying to juggle work and keep her children motivated and focused on their school work. One thing that has helped is carving out 30 minutes a day to read for pleasure or dance along to music videos (current favorite is “Levitating” by Dua Lipa featuring DaBaby)!

“Another way we cope with challenges is through creative expression. For instance, we’ve made parols (Filipino Christmas ornamental lanterns) and foam mosaic art. We’re also making more homemade dishes, like arepas (Venezuelan cornmeal cakes).”

Helping to guide our kids through the pandemic hasn’t been easy. Jennifer Mushinskie , a senior communications officer/interim operations liaison at the UCPath Center in Riverside and her son grappled with the loss of high school experiences you can’t get back, while still dealing with the social anxieties that are rampant in the teen years.

“It's heartbreaking to see a screen with 30 kids and only the teacher is on video. The kids aren't required to be on camera, per the district, so the teachers are frustrated, and the kids won't go on camera. I have tried to get him on video but he won’t – saying “Mom, that’s embarrassing if I go on and no one else does.

“Waiting has been exhausting on the kids mentally and physically. It's been a rough road. Our kids witnessed area businesses and mall parking lots filled with cars and shoppers, but they weren’t allowed to play in a high school football game or another type of school sport. We watched the Superbowl, with fans in the stadium, but our children in California weren’t in school or on the field. My son was so frustrated with this and it broke my heart. I’m grateful things are starting to get better.”

For Annette Dwyer , an accounts receivable associate at UCPath in Riverside, the pandemic brought her husband to her, then took him away, before returning him again.

“I married my Welsh boyfriend in July 2019, and had barely started the immigration process for my husband in January 2020, which was expected to take 12-18 months. We planned to pass the time with short visits. He was scheduled to visit in March 2020 to spend time with us during spring break, and for us to have a mini-honeymoon of sorts. That all changed when the executive order was issued on international travel to the U.S. (He barely made it on the plane and through customs thanks to a photocopy of my passport.) He was locked down with us in March, ‘getting stuck’ here for almost four months. We were devastated when my husband was called back to work and had to return to the U.K. in July. We did not know when we would get to see him again and hoped his immigration interview would be soon. (At that point, we were waiting to hear from the embassy.) He ended up receiving his interview in August and his immigrant visa was approved within an unheard of seven-month timeline. He immigrated here at the very end of August.”

On finding strength in community/new families

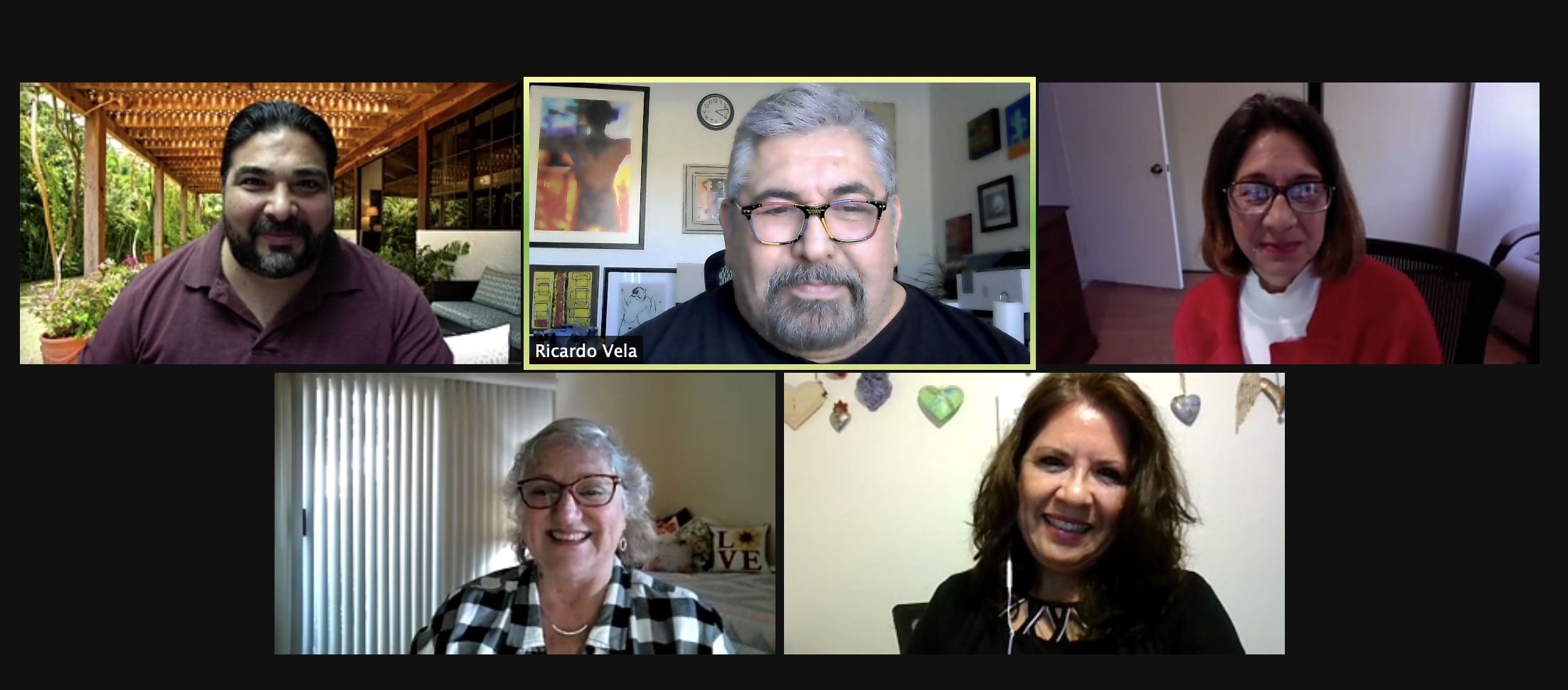

Ricardo Vela , who leads Spanish language news and outreach for UC’s Agriculture and Natural Resources division, has seen the pandemic turn his co-workers into family, the result of the intense bonds developed as they helped each other through the crisis. Several of his family members fell seriously ill with COVID-19, but recovered. Some of his colleagues were not so fortunate, and he and his team struggled through those moments together.

“As a team, during the pandemic, we have grown closer together. Even when we have not been in the same place for over a year, we pushed each other to think outside the box to accomplish our work's goals. We did better than ever before.

“But despite our success we fell at times into depression and anxiety, for days. When one of my staffers lost her father, we fell into despair, wondering "who is next?" We saw how personal the pandemic could get. It stopped being another headline and became real and painful.

“We shared tears of despair, impotence, and at times of joy! As a team, we pulled it together, we stopped being co-workers, and we became a family.

“A year after, I can say we are stronger, resilient. We learned that distance is only a click away, that we can express that love in many ways. We are ready to face the ‘new normal.’”

Azure Otani , a second-year business administration major at UC Riverside, felt “scared, lonely and claustrophobic” when the pandemic began. To cope, she pushed herself to become more (virtually) involved on campus — and in doing so, found a new sense of community. Today she holds officer positions in several student groups and has even mentored freshmen via text message.

“When the virus basically shut down the world at the snap of a finger, I thought I wasn’t going to be able to accomplish anything. Instead, I’ve been able to teach and learn from other people, and help bring meaning to their lives, just like they’ve brought to mine. I’ve never met any of them in person, but I know that many of them would have my back. I feel a true sense of community and am grateful for what I’ve learned in the process — what I value, how I like to work and the importance of taking time to reflect.

“I will forever be more conscious of the people around me — whether that is recognizing that I don’t know what others are going through or keeping my mask on when I’m sick. Life is extremely short and we don’t know when we’re going to lose everything we have. I know how important it is to spend my time with loved ones and reach out to give back as much as I can.”

On embracing change — and science

Heather Buschman , Ph.D., is assistant director of Communications and Media Relations at UC San Diego Health and an instructor at UC San Diego Extension. Since the start of the pandemic, her team has shared scientists’ stories and fact-based public information. She also volunteered at a vaccination site. From her unique perspective, Buschman has seen the magnitude of the pandemic, and the remarkable strides we’ve made.

“I was in my office when I heard that schools were closing. I ran to tell a coworker and choked with emotion over the gravity of the situation. For more than a month, I’d been serving shifts as a public information officer in our incident command center, which activated to manage coronavirus patient care and protect health care workers. But until then the pandemic hadn’t really affected my family.

“Until they arrived at UC San Diego Health, I never believed we’d have COVID-19 vaccines by early 2021 — and yet here we are, administering multiple, highly effective vaccines since late 2020. I’m blown away by what the scientific community has accomplished with so many people working together, focused on a single problem, with appropriate funding. I’m proud to tell scientists’ stories and play a small part in distributing vaccines to our community. It’s truly historic.”

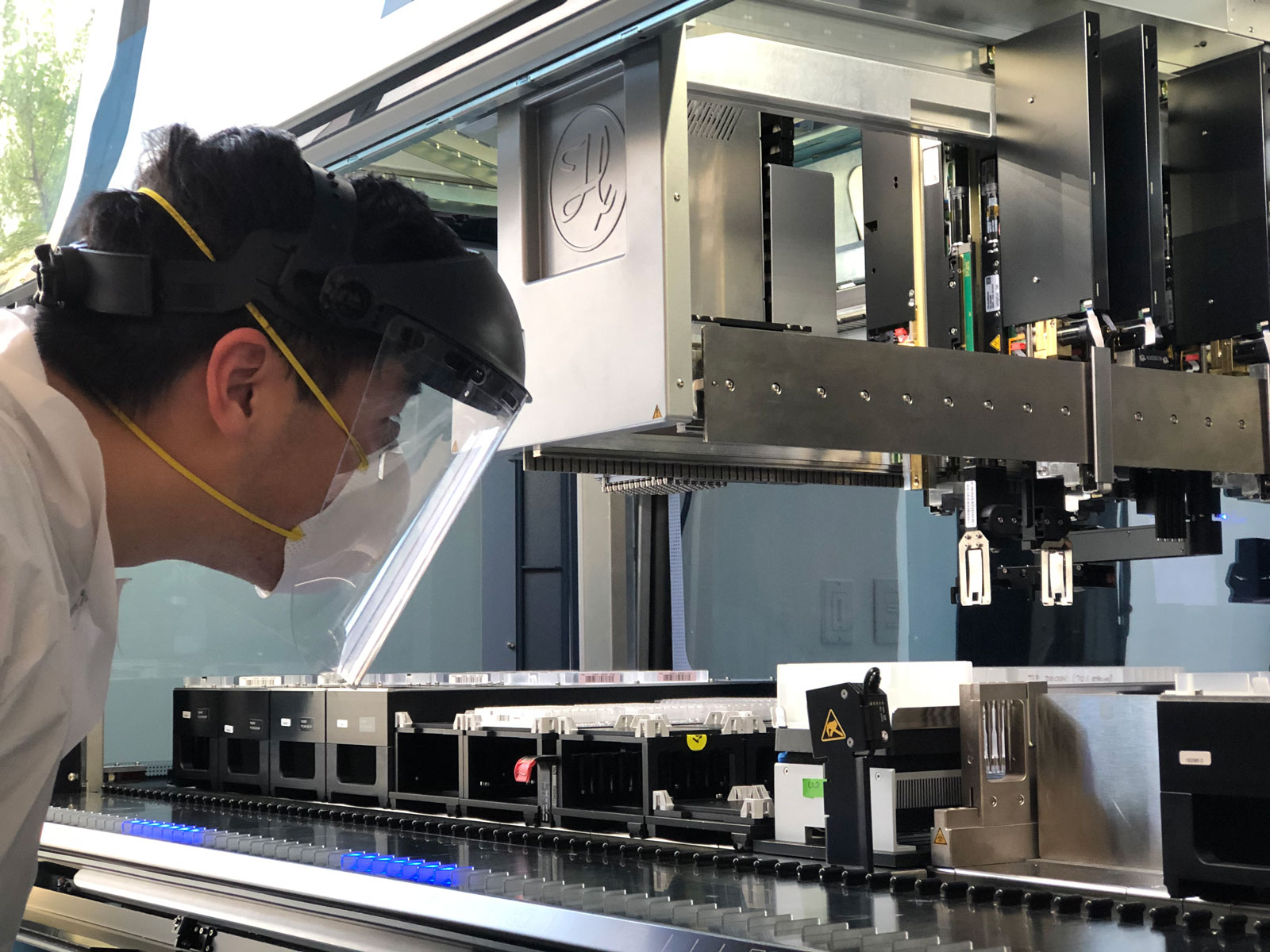

Connor Tsuchida is a graduate student in Jennifer Doudna’s lab at UC Berkeley, working on research related to the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR. When the pandemic hit, he and his colleagues at the Innovative Genomics Institute put aside their regular research to stand up a COVID rapid-results testing lab to meet the urgent need for COVID diagnoses. The transition from one new frontier of science to another wasn’t easy.

“For a [disease] testing lab, the concepts are not the same as genetic engineering, but the skills and technology you use is similar. We knew some of the techniques and protocols of diagnostic testing, and we were familiar with the equipment. That gave us a leg up so we weren’t starting from zero.

“One of the best things has been the opportunity to work with professionals from other fields: volunteer physicians from UC Berkeley’s student health center, people from public health — it’s a multi-disciplinary, team endeavor.

“For me, it’s also been a lesson in setting something up and then being okay with transitioning it to other people. There’s a controlling nature with research that if you are going to do it right, you need to do it yourself. It’s a good experience to hand off what you helped establish and see it take on a life of its own.”

Another bright spot: Tsuchida’s work in biomedical research now seems more vital than ever — and not only to those in the field.

There was so much work done in science and research before the pandemic that we absolutely were able to build upon when developing therapies and vaccines for COVID-19. I hope this will bring home the importance of that research and encourage everyone to support putting money into science.

Teresa Andrews, M.S., is an education and outreach specialist at the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at UC Davis, focusing on the workplace health and safety of farmworkers. Before the pandemic, Andrews and her team hosted in-person trainings for farmworkers and employers across California. COVID-19 forced them to reinvent their approach while maintaining connections with agricultural communities.

“We adapted our interactive activities to a virtual platform and started learning all we could about what farmworkers needed to know about COVID-19 and how employers could reduce workplace infections. Our goal was to be a resource, alleviate fears and empower workers and employers with the knowledge they needed to operate within this new reality.

“Since then, we’ve mastered the use of technology to fill the gap and stay connected. We offer more presentations and workshops than ever before and are reaching more people throughout our region, connecting with workers wherever they are. It brings me satisfaction to counter fears with science; to help explain concepts that can seem abstract to people — what a virus is, how your body responds, and what you can do to reduce the risk of infection — in language that’s easy to understand.”

Paul Kasemsap , an international student from Thailand, stayed close to campus partially to care for the plants he studies. But he also found himself drawn to the local Davis community, volunteering with the food bank to bring groceries to those most at-risk for COVID-19, so they didn’t have to risk trips to the store.

“After this is over, I hope we continue to take care of and check in with each other. I had indeed been taking in-person interactions and small talk for granted. But the pandemic showed me how powerful a role social support plays in our life. I hope we continue to tell our loved ones how much we love them and appreciate their support. Don't wait until the next pandemic!”

Aaron Zachmeier , UCSC Online Education instructional designer, helped hundreds of faculty put their classes online virtually overnight.

“Before the pandemic, the unit I'm in, Online Education, worked with a relatively small number of faculty on online and hybrid courses. We were kind of a boutique unit. When the shut-down happened, we started working with people all over campus.

“My colleagues and I created all sorts of resources to help with the transition to remote teaching and learning and remote working: workshops, self-paced courses, videos, text tutorials, checklists, infographics.

“We had a chat/discussion space that we opened up to all staff and faculty for the pandemic, and it has now become a lively place that spans departments and administrative units. People ask questions and have conversations about technology, teaching, and policy. Those conversations will continue.

“All of those people who started working together to facilitate the transition to remote are still talking regularly. They'll keep talking. That's a wonderful change.”

On improvising

Frida Hernandez is a Class of 2020 UC Berkeley grad. As the first in her family to graduate from college, she was looking forward to celebrating her big day with her family. While a virtual graduation wasn’t what she had hoped for, she was still able to share her accomplishments alongside her family at home in San Diego.

“Graduating in the middle of a pandemic as a first-gen student was tough because I felt the pressure to have my next steps all figured out to make my family proud. I have two younger siblings who are currently in high school, so I wanted to set a good example for them. Luckily, I was able to find a job in my field and I am so grateful I did. Landing my first full-time job in the middle of a pandemic gave me a new perspective on life because I was thankful to find some stability amidst all the chaos. I’ve really enjoyed spending time with my family (in my household) during this time. I moved back in with them after graduation and I’m grateful we have each other during these difficult times.

“As we begin to resume ‘normal’ life, I will live my life with more intention and gratitude. I hope to make up for all the celebrations I missed out on during this past year, such as my college graduation and numerous birthdays.”

In normal times, UC Santa Barbara’s Saameh Solaimani works as an early education specialist at the campus child care center. When the pandemic forced it to close, Solaimani quickly found new ways to help UC families by starting a website, www.ourchildrenscenter.org , that provided a high-quality resource for early child educators and those with young children.

“To see the pivot that so many teachers have made to ensure the healthy development of their students and learning communities, from pre-school all the way through higher-ed, has been incredible. These circumstances have reaffirmed what I knew to be true: That we, in the field of education, got into this work with hope for a better future and we are relentless with that hope, which is what keeps us going.”

Glenn Beltz is a mechanical engineering professor and associate dean at UC Santa Barbara. When the pandemic first hit, he saw first hand that family circumstances made online learning difficult for many students — there were no simple solutions. He and his academic advising team rose to the challenge by providing individual guidance to help as many students navigate the situation as possible. The Academic Senate’s decision at UC Santa Barbara to allow flexibility with pass/no pass grading was a huge help for students, allowing courses to count toward their degree requirements.

His own family faced different, but equally challenging circumstance with online learning.

“I am a parent so the kid aspect strikes a nerve. It has been rough. My wife and I have 2 kids, a daughter in 10th grade and a son in 4th grade. It has been particularly difficult with my son, who is autistic. Every autistic kid is different, but there is no way you could get my son to sit in front of a Zoom session for hours on end. No way at all. I fear that much of this past year will be a lost year in terms of his education. Fortunately, in January ’21, his elementary school worked out a protocol to be able to take him and a few other special-needs kids back. That has been a godsend.”

But he expects to take some positives forward.

“There are many aspects of teaching that I hope will remain in the long term. I think it’s awesome that students can pull a set of notes online from whatever I taught on a given day or even pull a recording of the lecture. Sure, that kind of stuff occurred in former times, but it was not widespread. I don’t think I will ever give a paper-based, sit-down exam again. I like being able to administer and grade exams online via various tools that are available.”

Top photo: One of Frida Hernandez’s journals from the pandemic.

Keep reading

Why emotions stirred by music create such powerful memories

Study shows the dynamics of people’s emotions mold otherwise neutral experiences into memorable events.

Following the mission to improve Central Valley health care

UC Merced breaks ground on a new Medical Education Building, scheduled to open in 2026.

The space between: Self-care and reflection during a pandemic

On my daily walk the song “The space between” by Dave Matthews Band popped up on my playlist. I hadn’t heard that song in probably 5 years. While a different context from Matthews’ narrative of a tumultuous romantic relationship, I found that the title—“The space between”—as a perfect characterization of where we find ourselves today. The space between free and house-bound, safe and in peril, grateful and resentful. Many of us are figuring out how to live in this state of limbo as we wait to find out when life will return to some semblance of “normal”, if that is even possible or desirable. From living through the vast ramifications of COVID-19, we also might find our emotions and thoughts bouncing to and from the extremes more freely, showing us greater fluctuation more so than in pre-pandemic times.

While walking and listening to Dave Matthews, I processed my fluctuating emotions and thoughts. One of the emotions that regularly accompanied me in my daily walks was guilt, and this day was no different. Guilt had visited me in waves for the past few weeks for a multitude of reasons: for having the privilege not to worry about potable water or shelter; for not giving back to my community as much as I could; for not helping my children with their school work as much as possible and allowing them to have almost unfettered access to technology during the work day; for sleeping until 10:45 AM on a Saturday when I could be grading or finishing a manuscript review. I even felt guilty about feeling guilty. I could go on. This list is by no means exhaustive. Yet, I had to stop myself, I was approaching the event horizon. I paused to wonder: What if I reframed these feelings of guilt and processed them within the context of a global pandemic?

These are not normal times. This is a colossal understatement. Our world has been upended and the finish line is only discussed in hypotheticals. I found myself in that downward spiral because I failed to situate what I was doing, or not doing, in the extreme present circumstances of COVID-19. When I remind myself that I am working and homeschooling my children while living during a pandemic, I also have decided to remind myself to reframe how I evaluate my progress. I am trying to value what I have been able to do—teach my classes, connect with students, have lunch with my children, connect with friends through Zoom—and believe I have something to be proud of. I try to compare myself less to others and to my abilities before COVID-19. “Try” is the operative word.

It is a process, but I am slowly letting go of my pre-pandemic mindset. Some questions I have been intentionally pondering, that you could ask yourself too, are:

- How can I show more kindness and grace to myself?

- How can I extend this kindness and grace to others?

- How can I reframe “should haves” or “ought tos” and view what I have done as valuable and commendable?

- How can I reframe “should haves” or “ought tos” and view what others have done as valuable and commendable?

- What two or three practices will help me through the uncertainty?

- When working with students, how can I model reframing for them? How can I help them process their experiences, emotions, and expectations during this time?

Like many, I am still figuring out the answers to the questions above. I grapple with them daily, but I have found that self-care through reframing, like all habits, is starting to take root after regular practice. Some resources that have helped me to reflect, reframe, and practice self-care are:

- Why “stillness” is crucial for your brain during this pandemic , by Steph Yin

- These phrases will help you reframe a negative mindset , by Marina Khidekel

- How to protect your well-being at work during a crisis , by Jessica Lindsey

- Greater Good guide to well-being during Coronavirus , by Greater Good

I wish you kindness and grace during these uncertain times. Please remember that you are enough and are doing enough, especially in this space between.

Recommended Stories

Coping with crisis on the enneagram scale, happy birthday, mom.

- About University Overview Catholic, Marianist Education Points of Pride Mission and Identity History Partnerships Location Faculty and Staff Directory Social Media Directory We Soar

- Academics Academics Overview Program Listing Academic Calendar College of Arts and Sciences School of Business Administration School of Education and Health Sciences School of Engineering School of Law Professional and Continuing Education Intensive English Program University Libraries

- Admission Admission Overview Undergraduate Transfer UD Sinclair Academy International Graduate Law Professional and Continuing Education Campus Visit

- Financial Aid Affordability Overview Undergraduate Transfer International Graduate Law Consumer Information

- Diversity Diversity Overview Office of Diversity and Inclusion Equity Compliance Office

- Research Research Overview Momentum: Our Research UD Research Institute Office for Research Technology Transfer

- Life at Dayton Campus Overview Arts and Culture Campus Recreation City of Dayton Clubs and Organizations Housing and Dining Student Resources and Services

- Athletics Athletics Overview Dayton Flyers

- We Soar We Soar Overview Priorities Goals Impact Stories Volunteer Make a Gift

- Schedule a Visit

- Request Info

Explore More

- Academic Calendar

- Event Calendar

- Blogs at UD

- Erma Bombeck Writers' Workshop

Things I Learned During the COVID-19 Pandemic

By Antoinette Pecaski

There are things to learn even in the most challenging of times, and sometimes it’s what we learn in those everyday moments of life that gives us a renewed perspective.

I learned to appreciate the big things. Like toilet paper, paper towels, hand soap. I nearly fell on my knees and wept when I spotted a lone bag of bread flour on the grocery shelf.

I learned that woman does not live by bread alone. On my first foray to the grocery store I prepped like I was going out for a night on the town. Eye shadow, mascara, eyeliner, foundation, blush and, of course, lipstick. I looked in the mirror and said, “Where have you been?” No one in the store could see my efforts. But, it felt so “normal,” even if it did look like I was robbing the place.

I learned to appreciate the really, really big things. The sight of my grandchildren’s faces on Facetime, the sound of my grown children’s voices on the phone, the warmth and support of my husband’s presence, the sound of my friends’ voices on the phone. My heart would swell with affection, my spirit parched with the need for friendship, for companionship, for a sense of normalcy.

When we could finally bubble, I learned to share my Italian heritage with my grandchildren (and appreciate it more myself). “Look,” I said as I gave them each some homemade dough. As their little hands kneaded and shaped the dough, I told them about the small mountain village where I was born. “Nana taught me this when I was a little girl, and her mother taught her and her mother taught her, going back many generations in our family.”

As we shaped the dough into pasta and gnocchi and lasagna noodles, I told them, “You know, they had to prepare their own food back then. There were no Sobeys’ or Pizza Huts.” I winked at them, “and that’s how RaRa caught DinDin.” But, I didn’t tell them that when we got married, I said to DinDin, “You do realize that there are lots of Sobeys’ and Pizza Huts!”

I learned to upgrade my computer skills. “You know,” I said to my son on the phone, “I’ve learned to do all kinds of stuff online: order groceries, pay my bills, order our new printer, and (my chest nearly bursting with pride), I actually programmed our new printer to our computer!” I didn’t tell him about the naughty words that assisted the process.

“That’s great Mom. Welcome to 2004.”

“Hey, listen,” I said, “I did all my university papers on that old rusty Remington Rand typewriter in the basement. You probably don’t even know what Whiteout is!"

I learned to channel my pioneer spirit. At the beginning of the pandemic, when we were afraid to venture out even to the grocery store, I learned to be resourceful. We needed hamburger buns. “No problem, I’ll make them.” Of course, they turned out like Frisbees and even the grandchildren wouldn’t eat them. And they eat everything!

I researched how to make your own hand sanitizer, homemade soap and lavender oil. I thought it prudent to be prepared for anything.

I cut my husband’s hair. He is a brave man. I viewed YouTube videos, bought barber scissors, and then kept my fingers crossed (obviously not literally). I’m happy to say he still has two ears and neither of them is pointy…although I did stab myself a few times.

And I learned to find solace and hope in nature. When my Dogwood tree bloomed in May after almost dying the previous year (it had to be transplanted), I was overjoyed, and saw it as a sign of hope.

When I spotted a small green weed with its small white and yellow flowers, defying its bed of gravel, I took its picture. Its tenacity to survive, to thrive and to flourish despite its adversity was overwhelming. Now, its picture is memorialized on my fridge, a constant reminder of what hope and courage look like.

And, when the pandemic is over, and we are free again, I think we will all have learned, that there are no little things in life. We will look at the world, like my little green plant, with renewed vigor and courage and a better understanding of this gift of living.

— Antoinette Pecaski

Antoinette (Toni) Pecaski is a writer of humorous essays from Ontario, Canada. She seeks to find the humor in our everyday lives and believes humor helps us to connect with each other. She takes the advice of Mark Twain to heart: “Humor without a tinge of philosophy is but a sneeze of laughter.” She is currently working on her book, My Mother Gave Me Booze for Breakfast.

Who's Publishing What: Black Dog, White Couch, and the Rest of My Really Bad Ideas

Hot stuff in the kitchen.

Caring for the self and others: a reflection on everyday commoning amid the COVID-19 pandemic

- Reflective Essay

- Published: 24 August 2020

- Volume 2 , pages 243–251, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Chun Zheng 1

We’re sorry, something doesn't seem to be working properly.

Please try refreshing the page. If that doesn't work, please contact support so we can address the problem.

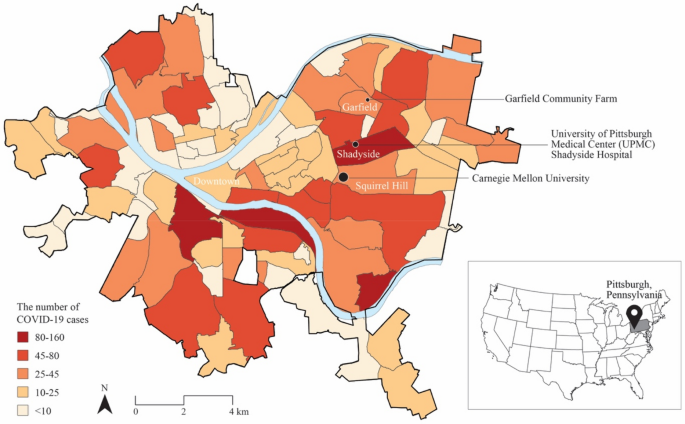

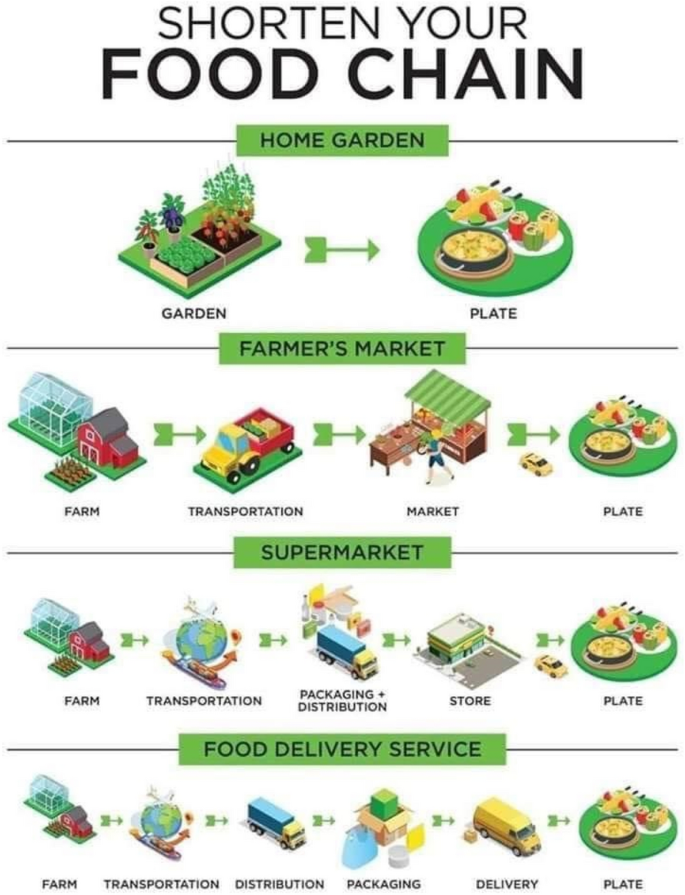

In this essay, I share my experiences and reflection on fighting the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of a Chinese student residing in Pittsburgh, USA. Three examples of “commoning”—acts of managing shared resources by a group of people—reveal the importance of care and collaboration in the time of uncertainty. First, when COVID-19 posed a threat to the food supply chain, community gardens and home gardening ensured food security and enhanced mutual support. Second, the emergence of online activities of teaching, learning, and collaborating presented an opportunity of having more collective, equitable, and diverse formats of virtual communities. Lastly, volunteering in the distribution of “Healthy Packs,” I witnessed the nurture of a sense of belonging and a connection with home in the student community. These examples suggest that facing the crisis, care-driven commoning activities at the individual, everyday level lay the foundation for large-scale collaborative systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reinventing community in COVID-19: a case in Canberra, Australia

Community-Engaged Learning: Sticky Learning About the Social World

Problemaufriss: Caring Communities als Mit-Wegbereiter für eine sich erneuernde Gesellschaft

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Commoning in a crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic is sweeping the planet. We, as individuals in the extended human family, are living through a crisis together. Within the vast and daunting global crisis are changes to every person’s daily life. These changes reveal the normally hidden human needs of care and collaboration and force us to re-invest in ourselves and our communities. In this essay, I share my personal experiences since the beginning of the pandemic and my observations of care-based everyday commoning activities over this period from the perspective of a Chinese student residing in Pittsburgh, USA (Fig. 1 ). Commoning, as defined by Gibson-Graham et al. ( 2013 ), takes place when a group of people is motivated by an ethic of care for a flourishing and sustainable common future and decides to manage shared resources in a collective manner. After discussing three examples of everyday commoning: gardening as commoning, online sharing as commoning, and volunteering as commoning, I reflect on the potential of expanding the sentiment of care for ourselves and others into larger-scale collaborative networks.

Spatial pattern of COVID-19 cases in Pittsburgh neighborhoods. Locations mentioned in this paper are highlighted. The map was created by the author based on the open data accessed on July 28 from Allegheny County Public Health Department ( https://www.alleghenycounty.us/Health-Department/Resources/COVID-19/COVID-19.aspx ) and Esri ArcGIS Database ( https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-online/resources )

2 From one epicenter to another

January 23rd, the day before the Chinese Lunar New Year’s Eve, the news that Wuhan and three other surrounding cities were going into lockdown Footnote 1 struck all TV channels in China. While words of the spread of a new type of pneumonia had been circulating for days (Wee and Wang 2020 ), Wuhan’s lockdown marked the start of an unprecedented national struggle and later, a global crisis.

Although physically stranded overseas, I could hear the worry in my family and friends’ voices over the phone. The anticipated joy of the annual family reunion was completely overwhelmed. In the following month, tracking the number of confirmed cases and the death toll became my daily routine. Watching more and more cities turn into darker colors Footnote 2 on the color-coded live COVID-19 tracking map put me into fear and homesickness.

Subsequently, I observed, in Pittsburgh, USA, personal protective equipment (PPE) in nearby pharmacies were almost sold out by February (Fig. 2 ). I collected 80 masks from over 10 shops in our region, most of which were the last bundles left for sale, to mail to a police friend working at the frontline in China. By the time I was ready to mail out the package, all flights to and from China had been banned (Corkery and Karni 2020 ). The travel ban not only meant the package would not have guaranteed delivery in the foreseeable future, but also put me into the mentality of being cut off from my homeland. Throughout February, via WeChat, Footnote 3 family and friends shared stay-home updates, cheered up each other, and even guided me to prepare for a potential COVID-19 outbreak in Pittsburgh. Geographical separations and time differences didn’t prevent us from caring for and supporting each other.

Last of N95 masks left in a Home Depot, 13 miles away from central Pittsburgh (February 2, 2020. Photography provided by the author)

On March 16, when most students were in the spring break, Pittsburgh officially reported its first two cases, Footnote 4 which meant educational entities had to make different decisions. Pittsburgh heavily relies on its education industry. The student population takes up 27% of the total population of the city. Footnote 5 Therefore, schools, preceding other public and private sectors in the city, responded to the outbreak first by switching to online classes, which lowered the risk of infection and spreading of the virus in the city that might be caused by students’ domestic and international travel. Still, I believe more earlier actions could have been implemented citywide and nationwide, including social distancing, encouragement to wear masks, and cancellations of large gatherings, to name a few. Nonetheless, what seemed so obvious to me, or to any Chinese citizen living in the USA, turned out to be invisible to most Americans, especially politicians and decision makers. The US government was overly optimistic about the epidemic and focused its resources on political rivalries, thus missing early opportunities to contain the outbreak. Compared with the constant and rolling media coverage of self-help prevention measures in China, the American people were given confusing and sometimes contradictory information, which blurred the severity of the pandemic. The rest of the story is well known. The malfunction of the government, the partisan differences, the sacrifices of healthcare workers, the hoarding of living essentials and weapons, etc., have become new abnormal norms in the USA. In these selfish, divisive and confusing situations, it is inevitable for many to find alternatives to self-help.

The duality of my experiences in two epicenters—the USA and China—has inspired me to recognize and cherish the spirit of mutual support and sentiment of care from others, as well as rethink where we can individually begin to act upon and contribute to forming a more collaborative and interconnected world. It took a long time for the majority of the world to realize that “the well-being of the group is endangered by indifferent individuals, and that community means originally simply a pooling of duties” (Jones 2020 , para 9). As individuals, we are incapable of changing the irreversible crisis; our duties lie simply in small everyday commoning actions.

3 Care and commoning

Commoning is the act of managing and sharing material and non-material resources, of creating things together, and of cooperating to meet shared goals among a group of people (Bollier and Helfrich 2015 , p. 17; Džokić and Neelen 2015 , p. 15; Bollier 2014 , p. 15). The participants in commoning processes are people who prioritize care for one another. Volunteering, altruism, selflessness, peer-assistance, mutual support, and so on can all be considered synonyms of commoning (Bollier 2020 , para 10). Prior to the pandemic, the logic of commoning can be found in cooperatively managed forests, social currencies, open-source software, citizen-managed urban spaces, community gardens, cooperative housings, and more. Commoning has been and is prevalent around the world as an essential survival strategy, especially in challenging times (Troncoso 2020 ; Baibarac and Petrescu 2017 , p. 229). We can, moreover, note that when governmental or market systems fail in the crisis, more people are finding their ways to support others through commoning—for instance, in the USA, crowdsourcing masks and ventilators, and mobilizing food bank resources for the elderly living alone amid the COVID-19 pandemic. A critical emotional motivation behind these commoning activities is care.