- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry

A critical edition.

- Ernest Fenollosa , Ezra Pound , Jonathan Stalling and Lucas Klein

- Edited by: Haun Saussy

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Fordham University Press

- Copyright year: 2009

- Main content: 240

- Keywords: Literary Studies ; Literature ; Poetry

- Published: August 25, 2009

- ISBN: 9780823238347

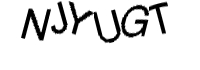

Enter the characters you see below

Sorry, we just need to make sure you're not a robot. For best results, please make sure your browser is accepting cookies.

Type the characters you see in this image:

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Characteristics

Chinese writing

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Omniglot - Chinese Script and Language

- Table Of Contents

Chinese writing , basically logographic writing system, one of the world’s great writing systems.

Like Semitic writing in the West, Chinese script was fundamental to the writing systems in the East. Until relatively recently, Chinese writing was more widely in use than alphabetic writing systems, and until the 18th century more than half of the world’s books were written in Chinese, including works of speculative thought, historical writings of a kind, and novels, along with writings on government and law.

It is not known when Chinese writing originated, but it apparently began to develop in the early 2nd millennium bc . The earliest known inscriptions, each of which contains between 10 and 60 characters incised on pieces of bone and tortoiseshell that were used for oracular divination, date from the Shang (or Yin) dynasty (18th–12th century bc ), but, by then it was already a highly developed system, essentially similar to its present form. By 1400 bc the script included some 2,500 to 3,000 characters, most of which can be read to this day. Later stages in the development of Chinese writing include the guwen (“ancient figures”) found in inscriptions from the late Shang dynasty ( c. 1123 bc ) and the early years of the Zhou dynasty that followed. The major script of the Zhou dynasty , which ruled from 1046 to 256 bc , was the dazhuan (“great seal”), also called the Zhou wen (“Zhou script”). By the end of the Zhou dynasty the dazhuan had degenerated to some extent.

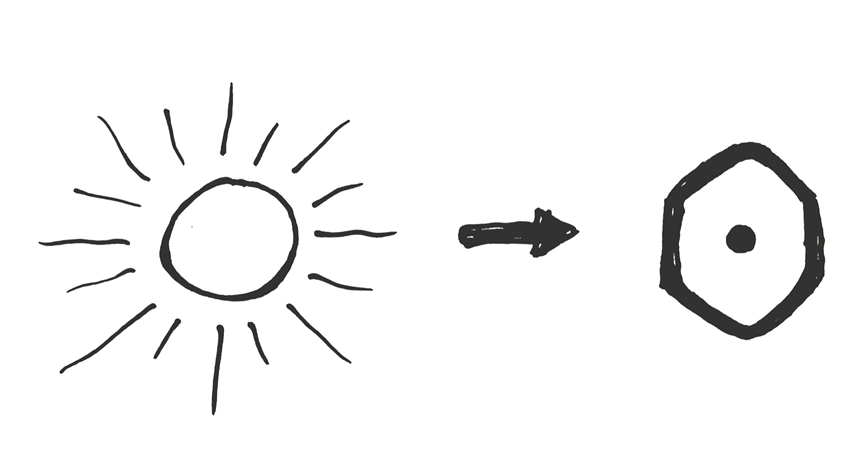

The script was fixed in its present form during the Qin period (221–207 bc ). The earliest graphs were schematic pictures of what they represented; the graph for man resembled a standing figure, that for woman depicted a kneeling figure.

Because basic characters or graphs were “motivated”—that is, the graph was made to resemble the object it represented—it was once thought that Chinese writing is ideographic, representing ideas rather than the structures of a language . It is now recognized that the system represents the Chinese language by means of a logographic script. Each graph or character corresponds to one meaningful unit of the language, not directly to a unit of thought.

Although it was possible to make up simple signs to represent common objects, many words were not readily picturable. To represent such words the phonographic principle was adopted. A graph that pictured some object was borrowed to write a different word that happened to sound similar. With this invention the Chinese approached the form of writing invented by the Sumerians. However, because of the enormous number of Chinese words that sound the same, to have carried through the phonographic principle would have resulted in a writing system in which many of the words could be read in more than one way. That is, a written character would be extremely ambiguous .

The solution to the problem of character ambiguity , adopted about 213 bc (during the reign of the first Qin emperor, Shihuangdi ), was to distinguish two words having the same sound and represented by the same graph by adding another graph to give a clue to the meaning of the particular word intended. Such complex graphs or characters consist of two parts, one part suggesting the sound, the other part the meaning. The system was then standardized so as to approach the ideal of one distinctive graph representing each morpheme, or unit of meaning, in the language. The limitation is that a language that has thousands of morphemes would require thousands of characters, and, as the characters are formed from simple lines in various orientations and arrangements, they came to possess great complexity.

Not only did the principle of the script change with time, so too did the form of the graphs. The earliest writing consisted of carved inscriptions. Before the beginning of the Christian Era the script came to be written with brush and ink on paper. The result was that the shapes of the graphs lost their pictorial, “motivated” quality. The brushwork allowed a great deal of scope for aesthetic considerations.

The relation between the written Chinese language and its oral form is very different from the analogous relation between written and spoken English. In Chinese many different words are expressed by the identical sound pattern—188 different words are expressed by the syllable /yi/—while each of those words is expressed by a distinctive visual pattern. A piece of written text read orally is often quite incomprehensible to a listener because of the large number of homophones. In conversation, literate Chinese speakers frequently draw characters in the air to distinguish between homophones. Written text, on the other hand, is completely unambiguous. In English, by contrast, writing is often thought of as a reflection, albeit imperfect, of speech.

To make the script easier to read, a system of transcribing Chinese into the Roman alphabet was adopted in 1958. The system was not intended to replace the logographic script but to indicate the sounds of graphs in dictionaries and to supplement graphs on such things as road signs and posters. A second reform simplified the characters by reducing the number of strokes used in writing them. Simplification, however, tends to make the characters more similar in appearance; thus they are more easily confused and the value of the reform is limited.

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Instigations. Together with an essay on the Chinese written character

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

5,153 Views

4 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on July 26, 2007

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry: A Critical Edition

In this Book

- Ernest Fenollosa, Ezra Pound, Jonathan Stalling, Lucas Klein

- Published by: Fordham University Press

- View Citation

First published in 1919 by Ezra Pound, Ernest Fenollosa’s essay on the Chinese written language has become one of the most often quoted statements in the history of American poetics. As edited by Pound, it presents a powerful conception of language that continues to shape our poetic and stylistic preferences: the idea that poems consist primarily of images; the idea that the sentence form with active verb mirrors relations of natural force. But previous editions of the essay represent Pound’s understanding—it is fair to say, his appropriation—of the text. Fenollosa’s manuscripts, in the Beinecke Library of Yale University, allow us to see this essay in a different light, as a document of early, sustained cultural interchange between North America and East Asia. Pound’s editing of the essay obscured two important features, here restored to view: Fenollosa’s encounter with Tendai Buddhism and Buddhist ontology, and his concern with the dimension of sound in Chinese poetry. This book is the definitive critical edition of Fenollosa’s important work. After a substantial Introduction, the text as edited by Pound is presented, together with his notes and plates. At the heart of the edition is the first full publication of the essay as Fenollosa wrote it, accompanied by the many diagrams, characters, and notes Fenollosa (and Pound) scrawled on the verso pages. Pound’s deletions, insertions, and alterations to Fenollosa’s sometimes ornate prose are meticulously captured, enabling readers to follow the quasi-dialogue between Fenollosa and his posthumous editor. Earlier drafts and related talks reveal the developmentof Fenollosa’s ideas about culture, poetry, and translation. Copious multilingual annotation is an important feature of the edition. This masterfully edited book will be an essential resource for scholars and poets and a starting point for a renewed discussion of the multiple sources of American modernist poetry.

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Conventions

- pp. xiii-xvi

- Fenollosa Compounded: A Discrimination

- Th e Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry: An Ars Poetica

- Appendix: With Some Notes by A Very Ignorant Man

- Th e Chinese Written Language as a Medium for Poetry

- Synopsis of Lectures on Chinese and Japanese Poetry

- pp. 105-125

- Chinese and Japanese Poetry. Draft of Lecture I. Vol. II.

- pp. 126-143

- Chinese and Japanese Traits

- pp. 144-152

- The Coming Fusion of East and West

- pp. 153-165

- Chinese Ideals

- pp. 166-173

- [Retrospect on the Fenollosa Papers]

- pp. 174-176

- pp. 177-208

- Works Cited

- pp. 209-216

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

Improve Chinese Essay Writing- A Complete How to Guide

- Last updated: June 6, 2019

- Learn Chinese

Writing can reflect a writer’s power of thought and language organization skills. It is critical to master Chinese writing if you want to take your Chinese to the next level. How to write good Chinese essays? The following six steps will improve Chinese essay writing:

Before You Learn to Improve Chinese Essay Writing

Before you can write a good essay in Chinese, you must first be accustomed with Chinese characters. Unlike English letters, Chinese characters are hieroglyphs, and the individual strokes are different from each other. It is important to be comfortable with writing Chinese characters in order to write essays well in Chinese. Make sure to use Chinese essay writing format properly. After that, you will be ready to improve Chinese essay writing.

Increase Your Chinese Words Vocabulary

With approximately 100,000 words in the Chinese language, you will need to learn several thousand words just to know the most common words used. It is essential to learn as many Chinese words as possible if you wish to be a good writer. How can you enlarge your vocabulary? Try to accumulate words by reading daily and monthly. Memory is also very necessary for expanding vocabulary. We should form a good habit of exercising and reciting as more as we can so that to enlarge vocabulary. Remember to use what you have learned when you write in Chinese so that you will continually be progressing in your language-learning efforts.

Acquire Grammar,Sentence Patterns and Function Words

In order to hone your Chinese writing skills , you must learn the grammar and sentence patterns. Grammar involves words, phrases, and the structure of the sentences you form. There are two different categories of Chinese words: functional and lexical. Chinese phrases can be categorized as subject-predicate phrases (SP), verb-object phrases (VO), and co-ordinate phrases (CO). Regarding sentence structure, each Chinese sentence includes predicate, object, subject, and adverbial attributes. In addition, function words play an important role in Chinese semantic understanding, so try to master the Chinese conjunction, such as conjunction、Adverbs、Preposition as much as you can. If you wish to become proficient at writing in Chinese, you must study all of the aspects of grammar mentioned in this section.

Keep a Diary Regularly to Note Down Chinese Words,Chinese Letters

Another thing that will aid you in becoming a better writer is keeping a journal in Chinese. Even if you are not interested in expanding your writing skills, you will find that it is beneficial for many day-to-day tasks, such as completing work reports or composing an email. Journaling on a regular basis will help you form the habit of writing, which will make it feel less like a chore. You may enjoy expressing yourself in various ways by writing; for instance, you might write poetry in your journal. On a more practical side of things, you might prefer to simply use your journal as a way to purposely build your vocabulary .

Persistence in Reading Everyday

In addition to expanding your view of the world and yourself, reading can help you improve your writing. Reading allows you to learn by example; if you read Chinese daily, you will find that it is easier to write in Chinese because you have a greater scope of what you can do with the vocabulary that you’ve learned. Choose one favorite Chinese reading , Read it for an hour or 2,000 words or so in length each day.

Whenever you come across words or phrases in your reading that you don’t understand, take the time to check them in your dictionary and solidify your understanding of them. In your notebook, write the new word or phrase and create an example sentence using that new addition to your vocabulary. If you are unsure how to use it in a sentence, you can simply copy the sample sentence in your dictionary.

Reviewing the new vocabulary word is a good way to improve your memory of it; do this often to become familiar with these new words. The content of reading can be very broad. It can be from novels, or newspapers, and it can be about subjects like economics or psychology. Remember you should read about things you are interested in. After a certain period of accumulation by reading, you will greatly improve your Chinese writing.

Do Essay Writing Exercise on a Variety of Subjects

As the saying goes, “practice makes perfect.” In order to improve your China Essay Writing , you should engage in a variety of writing exercises. For beginners, you should start with basic topics such as your favorite hobby, future plans, favorite vacation spot, or any other topic that you can write about without difficulty.

For example :《我的一天》( Wǒ de yì tiān, my whole day’s life ),《我喜欢的食物》( Wǒ xǐhuan de shíwù, my favorite food ),《一次难忘的旅行》( yí cì nánwàng de lǚxíng, an unforgettable trip ) etc.

Generally the writing topics can be classified into these categories: a recount of an incident,a description of something/someone, a letter, formulate your own opinion on an issue based on some quote or picture etc.

Takeaway to Improve Chinese Essay Writing

Keep an excel spreadsheet of 口语(Kǒuyǔ, spoken Chinese) –书面语(Shūmiànyǔ, written Chinese) pairs and quotes of sentences that you like. You should also be marking up books and articles that you read looking for new ways of expressing ideas. Using Chinese-Chinese dictionaries is really good for learning how to describe things in Chinese.

Online Chinese Tutors

- 1:1 online tutoring

- 100% native professional tutors

- For all levels

- Flexible schedule

- More effective

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via Email

Qin Chen focuses on teaching Chinese and language acquisition. She is willing to introduce more about Chinese learning ways and skills. Now, she is working as Mandarin teacher at All Mandarin .

You May Also Like

This Post Has 3 Comments

When I used the service of pro essay reviews, I was expecting to have the work which is completely error free and have best quality. I asked them to show me the working samples they have and also their term and condition. They provided me the best samples and i was ready to hire them for my work then.

This is fascinating article, thank you!

Thank you so much for sharing this type of content. That’s really useful for people who want to start learning chinese language. I hope that you will continue sharing your experience.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Project Gutenberg

- 74,114 free eBooks

- 14 by Ezra Pound

Instigations by Ezra Pound

Read now or download (free!)

| Choose how to read this book | Url | Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.html.images | 761 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.epub3.images | 400 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.epub.images | 408 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.epub.noimages | 320 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.kf8.images | 667 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.kindle.images | 619 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40852.txt.utf-8 | 601 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/40852/pg40852-h.zip | 378 kB | |||||

| There may be related to this item. | ||||||

Similar Books

About this ebook.

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Contributor | |

| LoC No. | |

| Title | Instigations Together with An Essay on the Chinese Written Character |

| Contents | A study in French poets -- Henry James -- Remy de Gourmont -- In the vortex -- Our tetrarchal précieuse -- Genesis -- Arnaut Daniel -- Translators of Greek -- An essay on the Chinese written Character, by E. Fenollosa. |

| Credits | Produced by Annemie Arnst & Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Internet Archive.) |

| Language | English |

| LoC Class | |

| Subject | |

| Subject | |

| Subject | |

| Subject | |

| Category | Text |

| EBook-No. | 40852 |

| Release Date | Sep 24, 2012 |

| Most Recently Updated | Apr 3, 2024 |

| Copyright Status | Public domain in the USA. |

| Downloads | 312 downloads in the last 30 days. |

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- More like this

- Preview Available

- Scholarly Journal

The Chinese Written Character as a Medium of for Poetry: A Critical Edition

No items selected

Please select one or more items.

Select results items first to use the cite, email, save, and export options

You might have access to the full article...

Try and log in through your institution to see if they have access to the full text.

Content area

The Chinese Written Character as a Medium of for Poetry: A Critical Edition. Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound. Haun Saussy, Jonathan Stalling, and Lucas Klein, eds. New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2008. Pp. xiv + 216. $25.00 (cloth).

The story of Ezra Pound's stroke of luck bears re-telling. In 1913, he met Mary McNeill Fenollosa at a dinner party hosted by the Indian poet and reformer Sarojini Naidu. Mrs. Fenollosa whose husband, Sinologue Ernest Fenollosa, had died in 1908, obviously took a shine to Pound, inviting him (as he reported to fiancée Dorothy) "to two bad plays & to dinner with [publisher] William Heinemann".1 A more momentous gift followed when Mrs. Fenollosa decided that Pound was the ideal person to assess and edit her late husband's notebooks. From this treasure-trove Pound would quarry an edition of Noh plays, thirteen translated poems that would provide the bulk of his pivotal collection Cathay, and the notes for what would become the short but pregnant essay The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Throughout his life, Pound would insist on the importance of this essay, describing it as nothing less than an "Ars Poetica, gorrdamit" and returning as late as 1958 in a retrospective account included here to Fenollosa's lecture notes as an antidote to "the filth of brain wash" apparently emanating from Yale and Harvard.

This lavish new edition of the essay marks its transition from the quasi-underground formats of Square Dollar and City Lights to the sort of status Pound claimed for it in his headnote to the 1936 edition: "a study of the fundamentals of all aesthetics." For the first time, we can review the several drafts of the piece alongside Pound's annotations. Also included are...

You have requested "on-the-fly" machine translation of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace human translation. Show full disclaimer

Neither ProQuest nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the translations. The translations are automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. PROQUEST AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the translations is subject to all use restrictions contained in your Electronic Products License Agreement and by using the translation functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against ProQuest or its licensors for your use of the translation functionality and any output derived there from. Hide full disclaimer

Suggested sources

- About ProQuest

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Fenollosa, Pound and the Chinese Character

In 1954 Ezra Pound published his translation of the third of the Chinese Classics under the title "The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius." (Harvard University Press) It was immediately recognized that these translations, or "translucences", as some call them, stood in a different category from the numerous ones that had preceded. Richard Wilbur is quoted on the dust-jacket as naming Ezra Pound "the first translator of our age." I.A. Richards salutes "Mr. Pound at his best." Achilles Fang, in the Introduction to the volume, notes that "Pound now emerges as a Confucian poet."

There is here an intriguing element of mystery. Pound is not a professional student of the Chinese language, like Legge, Giles, Waley, Karlgren, and others who have tried their hand at translating the Book of Odes into English. We do find the dust-jacket proclaiming that "Pound's translation ... is the culmination of forty years of Chinese study," but it is doubtful whether Pound himself would wish to make that statement. We shall see that he expressly disassociates himself from "scholarship", which he is likely to view as smothering the art of translation, rather than making a contribution to it. The question that we pose may then be stated as follows: Does the superiority of Pound's translation lie in the end-product , the superior style and poetic quality of his English, or does it lie at the source , a deeper penetration into the mind and art of the Chinese poet who furnishes the raw material for the translation? An answer to this question is of interest to all who study Chinese, whether for finding their own pleasure therein, or for giving pleasure to others through translation.

It does not appear that Pound has anywhere offered an exposition of his method in translating Chinese. There is no doubt, however, that he has been continuously stimulated by a short essay entitled "The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry", composed in the main by the late Ernest Fenollosa. Pound received the manuscript of this essay after the author's death in 1908. He edited it, and in some introductory paragraphs dated 1918 described it as "a study of the fundamentals of all aesthetics." According to "A Preliminary Checklist of the Writings of Ezra Pound" by John Edwards (New Haven, 1953) the essay was first published by Pound in 1920 (No. 26). It was republished by him in 1936 (No. 52) as the first issue of a projected "Ideogramic Series" which seems not to have been continued. In the preliminary Note to Pound's translation of "The Analects" that appeared in the Hudson Review in 1950 (No. 635) the essay is referred to in the following paragraph: "During the past half-century (since Legge's studies) a good deal of light has been shed on the subject by Fenollosa (Written Character as a Medium for Poetry). Frobenius (Erlebte Erdteile) and Karlgren (studies of sacrificial bone inscriptions)." We may not be justified in saying that Pound learned from Fenollosa how to translate Chinese, but we are certainly justified in assuming that he held him in high regard. And this leads us naturally to an examination of the latter's ideas.

Fenollosa's essay is a small mass of confusion. Within the limits of forty-four pages he gallops determinedly in various directions, tilting at the unoffending windmills. This follows, perhaps inevitably, from the fact that one of them is logic. On pages 61, 64, 75, 76, 77, 78 (I refer to the edition in the Square Dollar Series, 1951) he thrusts his random spear at logic that "has abused the language," logic that "deals in abstractions," logic that establishes "classifications." These are but preliminary skirmishes, for the central sin of logic, as it relates to Fenollosa's various theses, is that it has spawned "grammar". It is hard, at this time, to determine where the camp of his enemies lay, since he never names them, but he attributes to "professional grammarians" definitions of the sentence (60-61) and formulations of the copulative (63-65) that seem highly repugnant, at least to him. It is noteworthy that, fifty years later in 1958, the same quixotic tournaments persist. Fenollosa was not clear whether the grammarian was one who described how a language operated or one who prescribed how it should operate. His conceived enemy was the latter, just as it is the nemesis of every would-be writer from sixth grade through freshman college composition who feels himself worsted in contest with a grade-dispensing authority that penalizes every deviation from its own established norm. In so far as Fenollosa was fighting to protect poetry from what he viewed as the stifling palm of a grammarian's commandment, one may sympathize full-heartedly with him. But in our age this issue is a corpse, and the palm is lifeless. No linguist or grammarian elects himself a dictator, nor is he antagonistic to poets. Contrariwise, their functions complement -- the one to create, the other to record.

Having eased himself of his rancor toward prescriptive grammarians, if such there were, Fenollosa moves happily in his essay to the post of descriptive grammarian of Chinese. Whereupon many curious things happen. Fenollosa claims the sentence form to be "forced upon primitive men by nature itself." (p. 62) This form "consists of three necessary words," (p. 63) the agent, the act, and the receiver, in that order. So "the form of the Chinese transitive sentence, and of the English, exactly corresponds to this universal form of action in nature." As an example: "Farmer--pounds--rice." Fenollosa's prose at this point is exceptionally eloquent, and well worth reading. Since nature is not static, but in constant flux, its movement is an unending transfer of power from one point to another. The essence of this movement lies in the transfer, but the transfer is not possible without two terminals. A transitive sentence, --actor, action, receiver--"brings language close to things , and in its strong reliance on verbs it erects all speech into a kind of dramatic poetry."

It should be noted that what has chiefly happened here is the substitution of Nature for the sixth-grade schoolmarm, and that Fenollosa has relapsed into the role of prescriptive grammarian, however much he may detest it. As a symbol of authority, Nature may be more awesome or more sympatisch than the minion of the Board of Education, but in principle we have the same thing. Sentences must contain a subject, verb, and object, in that order , not because Miss Cherivitsky says so, but because Nature has so ordained. Try to beat that! It is highly ironic that the oriental language with which Fenollosa was best acquainted was Japanese, which disobeys these laws of Nature. The three "necessary" elements are expressed in Japanese in the perverse order of subject, object, verb. In two cavalier sentences Fenollosa disengages himself from this embarrassment. Japanese, and some other languages, can behave differently because they have "little tags and word-endings." (p. 63) And with this denouement of a shift back to the descriptive, the curtain comes down on the comedy. Japanese words do have little tags and word-endings. And the skeleton word-order is subject, object verb. But unless Nature deliberately contrived outlandishness for the Japanese and Germans and others whom we have sought in recent decades to confound, there is little left of that universal order.

After settling the natural form of the sentence, Fenollosa discusses parts of speech, and introduces the topic with two brilliant sentences that place him still in this particular regard ahead of our time. His statement is: "Every written Chinese word is properly ... an underlying word, and yet it is not abstract. It is not exclusive of parts of speech, but comprehensive; not something which is neither a noun, verb, or adjective, but something which is all of them at once and at all times." (p. 68) If Fenollosa had had the linguistic training to work out the implications of that statement, or if anyone of us now had the ability, a new descriptive grammar of Chinese could be initiated. Scholars, and grammarians as well, who deal with written Chinese, expecially [sic] poetry, are quite persuaded to follow Fenollosa in the view that parts of speech do not exist. But it is difficult to describe, perhaps even to imagine, such a linguistic condition in terms of another language like English where word-classes are still of some importance. Fenollosa hints that Chinese, unlike English, has "a common word underlying at once the verb 'shine', the adjective 'bright' and the noun 'sun'." (p. 68) Pound, in a very perceptive note, suggests that English could use 'to shine' (verb), 'shining' (adjective), and 'the shine' (noun). It might prove awkward to apply this on a thorough-going scale in English, but at any rate we have a true and fruitful line of thought.

Fenollosa characteristically shifts position as soon as he has taken it. "One of the most interesting facts about the Chinese language is that in it we can see not only the forms of sentences, but literally the parts of speech growing up, budding forth one from another." At that he proceeds to discuss Chinese nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, and even prepositions and conjunctions, with the purpose of showing that all other classes are derived from verbs. Having acted alternately as descriptive and prescriptive grammarian, Fenollosa here assumes the role of historical grammarian. The question whether at any particular period, say the period of T'ang poetry, written Chinese has or has not parts of speech is one to be settled by a descriptive process. If it is found to have parts of speech, then the fact that these arose at some remote period by differentiation from a single class of verbs is quite irrelevant. It would be of historical interest to discover the stage in time at which all elements of the Chinese written language were verbs, but this is not possible, first, because there can be no definition of what constitutes a verb in classical Chinese, and second, because we have no recorded texts in which there is not already a highly differentiated class of grammatical particles.

Such theses of Fenollosa, and others that we shall omit from discussion,--theses tossed out in confusion and self-contradiction, --are designed to preach the simple principle that strong transitive verbs add vigor and vitality to poetry. If this was a new principle in Fenollosa's time, he must be given credit for its forceful presentation, but it is hard to see why it was necessary to shore it up with questionable Chinese props. Fenollosa states that "the great number of these [Chinese] ideographic roots carry in them a verbal idea of action ... a large number of the primitive Chinese characters ... are shorthand pictures of actions or processes." (p. 59) "In translating Chinese, verse especially, we must hold as closely as possible to the concrete force of the original, eschewing adjectives, nouns, and intransitive forms wherever we can, and seeking instead strong and individual verbs." (p. 65-6). If the poetic principle is solid, its application need not be limited to translation from the Chinese, but should be fundamental in all poetic creation or translation alike. But, of course, if Chinese in its own structure relies heavily on strong transitive verbs, --and this has been a central theme, --then it makes more than usual demands on the translator so to represent it. And with no trace of humor Fenollosa presents us with a typical line of Chinese poetry "MOON - RAYS - LIKE - PURE - SNOW." (p. 56) Of the five words three are indisputable nouns, one is an adjective, and the fifth, 'like', is not much more than a variation of the copula. There is no verb in the lot, let alone a "strong individual verb." But the line is typical.

We have now reached a point of despair. The complete Chinese poem of twenty syllables will be reproduced later, when it will be found that eleven of the twenty are defined as nouns, three as adjectives, two as copulative variants, one as intransitive verb, two as of doubtful classification, and only one, 'admire', as a transitive verb with fairly low dynamics. A paraphrase of the whole poem, which appears to be the joint effort of Fenollosa and Pound, reads as follows: (p. 86)

There are perhaps two places where the "strong verbal action" shows through: 'falls on' and 'casts'. Unfortunately, neither one has any counterpart in the Chinese original. 'Admire' is a pretty wistful sort of verb. 'Turning' is intransitive. 'Full of' is properly a passive. (Being poet neither by inclination nor training I ask in childish wonder why the second line as English is not rendered. "Bright stars fill its boughs". And I return to this question later.) On the other hand we have ten nouns and three adjectives. Then the notion that Chinese poetry is overloaded with strong transitive verbs, and that its translation requires use of strong transitive verbs, is, to put it mildly, shot to hell. But if the thesis has failed of support in the arguments so far adduced, it is possible that it may be substantiated through a consideration of the Chinese written character. This is the reason for the title of the Essay, and to this subject we now turn.

We have already quoted Fenollosa's remark that "a large number of the primitive Chinese characters are shorthand pictures of actions or processes." He goes on to say, "but this concrete verb quality, both in nature and in the Chinese signs, becomes far more striking and poetic when we pass from such simple original pictures to compounds." (p. 59) The facts behind these statements are the following. The Chinese unit of writing is a "graph" or "character." In printed texts all characters occupy equal space and appear equally independent, though they vary greatly in complexity from a single stroke to a conglomeration of thirty or more. Many of the simpler characters can be described in such a way as to show pictorial origin still recognizable despite change or distortion. Such forms, of which Chalmers in 1882 compiled a list of 300, are sometimes called "primitives." Another list that comes early to the attention of the student of Chinese consists of the 214 "radicals " or "keys " by which characters are generally arranged in dictionaries. Eighty percent of these are made up of eight strokes or less. The pictorial significance of many of these forms is a matter of debate that has been somewhat clarified in recent decades through the archaeological discoveries of inscribed shells and bones dating from as early as 1400 B.C. Apart from these, chief reliance has been placed on an etymological dictionary compiled around 100 A.D., in which 9353 characters were listed and analyzed with respect to their original shapes and meanings. Contrary to impressions current among westerners, only 364, or 3.9 percent of the characters, could at that time be traced to a pictorial origin.

Simple forms, as may be expected, recur in the more complex characters. Thus in a dictionary of less than 8000 characters the pictograph for 'mouth' is found as "key" in 378, and probably occurs, in one way or another, in 500 more. The pictograph for 'tree' has about the same distribution. Quite contrary to Fenollosa's view, the vast majority of the primitives whose pictorial origin is determinable are pictures of objects, and are translatable as nouns. Since the number of primitives is small, it follows that most Chinese characters appear as composites. The percentage in the etymological dictionary mentioned was 94.8. Nothing then seems simpler to the western mind than that, given the meanings of a few hundred primitives, the meaning of a composite is derivable from the sum of its parts. Once this view is adopted, the reading and translation of Chinese becomes a game that any number can play, and with infinite variety. For the association of a fish, an eye, and a roof, can suggest different things to different people. (That is why the Rohrschach tests are effective.) The odds against the meaning of a character being equal to the sum of the meanings of its parts are about fifty to one. But the two-percent chance seems sufficient to keep the game going and the players happy.

We are fortunate to have a complete record of such a game, played by Fenollosa and Pound as partners, and appended to the Essay on pages 84 and 85. This record is reproduced below. The Chinese text is a poem in four lines of five syllables each. The English words in capitals, except for two mistakes, are dictionary definitions, while below them are the analyses that should in theory produce the definitions.

The results of the analysis shown above cannot but be disappointing to those who have read Fenollosa's essay in hope and expectation. There is hardly a case where the dictionary meaning of a character shows any intelligible dependence on the meanings of the parts. And this despite the best efforts of the players to twist meanings to that end, an enthusiasm that has led in many cases to misreading or misinterpretation, as shown in the following notes:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 月 | 耀 | 如 | 晴 | 雪 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 梅 | 花 | 似 | 照 | 晃 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 可 | 憐 | 金 | 鏡 | 轉 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 庭 | 上 | 玉 | 芳 | 馨 |

- Correct. This is the only simple pictograph out of the twenty.

- The element at lower right is a pictograph of a bird, but there is no justification for equating this with 'flying'. There is, to be sure, an association of ideas.

- The elements 'woman' and 'mouth' are present, but it is not apparent how these suggest the meaning 'like'.

- The right hand part has nothing to do with sky except as it may describe its color. The word for which it stands can be rendered into English only by a periphrasis 'the color of nature'. In the spectrum it is blue, green, or even black.

- The upper part is rain. The lower, as it stands, is pictographic for 'hand'. The graph for 'broom' contains this element, but so do many other graphs which might equally well be suggested.

- On the contemporary level the right-hand part is unanalyzable. There is no element 'crooked', nor 'female breast, but it does include the graph 'mother'. The relation of all this to the meaning 'plum' is, in any case, mysterious.

- The element at lower right may easily be confused with 'spoon', but here it represents a man turned in the opposite direction from the normal.

- The right-hand element stands for 'by means of' or 'in order to', never 'try'. It is hard to see how this adds up to 'resemble'.

- The elements are all correctly identified.

- The graph in the text has been wrongly written. When corrected to the graph for 'star' it will consist of 'sun' and 'grow'.

- The two strokes here additional to 'mouth' are not 'hook', but a sign of exclamation.

- The element described as 'fire' is, in its present form, 'rice'. There is nothing identifiable as 'girl', while 'descending through two' is pictographic for two men back to back. Corrected analysis would hardly lead to 'admire (be in love with)'.

- This graph is not analyzable on the contemporary level.

- The meaning of this graph is 'mirror'. The elements have been correctly identified, but their total relevance is obscure.

- The upper right-hand part is not another 'carriage', but is supposed to be pictographic for 'yoked ox'.

- The meaning 'blend' is not represented here. There is an element 'shed' (a building) and an element 'court'.

- This is an indicative graph for 'top'.

- As the graph now looks it is 'king' and a dot, but it is not clear why this should mean 'jewel'.

- The meaning 'weeds' for this graph is the result of some misunderstanding. The upper element is 'grass' and the lower 'square', while the whole means 'fragrant'.

- The upper half of this graph stands for a musical instrument consisting of suspended stones. The lower half is made up of 'sun' under 'grain', not 'tree'.

[ Fenollosa left the notes unfinished; I am proceeding in ignorance and by conjecture. The primitive pictures were "squared" at a certain time. E.P.]

| MOON | RAYS | LIKE | PURE | SNOW |

| bright + feathers flying | woman mouth | sun + azure sky | rain + broom cloud roof or cloth over falling drops | |

| sun disc with the moon's horns | Bright, note on p. 42. Upper right, abbreaviated picture of wings; lower, bird=to fly. Both F. and Morrison note that it is short tailed bird | Sky possibly containing tent idea. Author has dodged a "pure" containing sun + broom | Sweeping motion of snow; broom-like appearance of snow | |

| PLUM | FLOWERS | RESEMBLE | BRIGHT | STARS |

| tree + crooked female breast | man + spoon under plants abbreviation, | man + try = | sun + knife mouth fire | sun bright |

| probably actual representation of blossoms. Flowers at height of man's head. Two forms of character in F.'s two copies | does what it can toward | Bright here going to origin: fire over moving legs of a man | ||

| CAN | ADMIRE | GOLD | DISC | TURN |

| mouth hook | ( | gold + to erect sun legs (running) | carriage + carriage tenth of cubit | |

| I suppose it might even be fish-pole or sheltered corner | Present form resembles king and gem; but archaic might be balance and melting-pots | (?) Bent knuckle or bent object revolving round pivot | ||

| GARDEN | HIGH ABOVE | JEWEL | WEEDS | FRAGRANT |

| to blend + pace, in midst of court | king and dot | plants cover knife | ||

| : plain man + dot = | I.e. growing things that must be destroyed | Specifically given in Morrison as fragrance from a distance. M. and F. seem to differ as to significance of sun under growing tree (cause of fragrance) |

What then is wrong here? For something must be frightfully wrong. Just a complete misunderstanding of what Chinese characters are, how they were created, and how they function as speech symbols. A few illustrations may make this clear:

3. The third character of the poem is divisible into a pictograph 'woman' on the left and a pictograph 'mouth' on the right. At the earliest times that we know the word for 'woman' was nyo , and the word for 'like' happened also to be nyo , or something very close to it. Scribes then began by writing the pictograph 'woman' to represent phonetically the word 'like', leaving context to determine which was meant. This process is familiar to every child as rebus-writing, in which the picture of a stick of wood stands for 'would', or the picture of a bee plus the number four makes up 'before'. In Chinese a refinement was introduced by adding the sign for 'mouth', which in scores of characters gives a signal to be interpreted as follows: This character represents the sound nyo , which is, of course, the word for 'woman'. But in this case I mean the sound nyo that is not 'woman', and you will recognize it as the word 'like'.

7. The lower half of this stands for the sound hwa and hence the word for 'transformation' 'metamorphosis'. The word for 'flower' in archaic times was hhwa (voiced h as initial), and was written with a very different character. Sometime later there came into the language a word for 'flower', hwa , whether by dialect mixture or a sound shift we do not know. But scribes represented it phonetically with their existing character for 'metamorphosis', and later, for the sake of clarity, added above it the symbol for vegetation which was already present in the character for hhwa 'flower'. It will be noted that this process differs somewhat from that illustrated in 3, because there is a possibility that the two words 'flower' and 'metamorphosis' are really only one word in different extensions of meaning.

16. A true example of what has just been suggested for 'flower' is seen here. If the three strokes at top and left of this character be removed, the remainder stands for the sound dieng and the word 'court '. Now there is considerable physical difference between a 'tennis court' and the 'Supreme Court', although we get along in English with one word for both. Similarly in Chinese the word dieng came to mean both an open court in someone's front yard, and the court of the king, which was presumably enclosed. It then occurred to some fussy scribe to add the three strokes that picture a roof and a side wall, so that a palace dieng might be distinctive. He did not realize that such artificialities rarely work in language. Since there was only one word dieng , it could not matter to any but the most meticulous which way it was written. And, amusingly enough, in the poem we are examining, the symbol for dieng, though decked out for the eye with roof and wall, stands clearly for the dieng of the 'garden' variety.

A consideration of the last example will make clear why the approach of many westerners to Chinese is unrealistic. It is not the purpose of this article to teach Chinese, and it may seem to the reader that we have already become too technical. But it is impossible to say anything on the subject without emphasizing and reiterating that characters are symbols for sounds, and through sound are symbols for words. They are not a code for the deaf and dumb, nor a collection of pictures to entrance the eye. It is basic to the philosophy of Fenollosa, Florence Ayscough, Amy Lowell and other translators to believe that the quality of a line of Chinese poetry is chiefly determined by a picturesque choice of characters, and that lithe thought-picture is not only called up by these signs as well as by words, but, far more vividly and concretely." (p. 58) But the fact is that such images as appear through the sort of analysis illustrated above are not present in the mind of the Chinese reader, because he has never thought of them. They were unknown to the compiler of the etymological dictionary of 100 A.D. It is more than likely that they were unknown to the Chinese poet himself, who used the characters as arbitrary symbols for the words of his poem.

In the introduction to his translation of Tu Fu, Professor William Hung directs a gentle criticism at the professed method used by Florence Ayscough and Amy Lowell. "The basic assumption of the method was that the etymological derivations of the Chinese ideographs composing the lines in a poem were of great importance. Suppose there are two characters having the same meaning in current usage. Why should the poet choose the one instead of the other? The ladies believed that the choice was determined according to how well the "descriptive allusions" or the "undercurrent of meaning" would enrich the "perfume" of the poem." (p. 9) Professor Hung is of opinion that "a poet's discrimination between synonyms is very frequently concerned with the difference in sound values." We might go further to argue that sound values are the primary consideration. The assembling of twenty characters, however strong their perfume, does not make a Chinese poem.

In the specimen of poetry here reproduced, a number of formal requirements are shown. In the first place, the words are arranged in four lines of five syllables, each line syntactically complete. In the second place, the second and fourth lines rhyme, and the rhyming syllables are in the level tone. In the third place, the first and second lines show a word to word parallelism or contrast, so that the grammatical structure of both is identical. In the fourth place, with the dichotomy of tones into "level" and "oblique", the tone of each syllable in the first line is matched in the second line by a syllable of the opposite tone class. This tonal opposition appears also between the third and fourth lines. In the fifth place, the tonal pattern of each line is different. And finally, the poem has a unity of thought.

The tonal pattern of the poem is as follows :

We do not suggest that these rigid conditions are ideal for the creation of poetry, but merely that such conditions were generally imposed on the T'ang poet. And it is quite beyond reason to imagine that after satisfying these conditions the poet had time to worry over the pictorial stimulation that particular characters might furnish to future western readers. Perhaps the supreme irony is the fact that we have no real knowledge of precisely how a T'ang poet, for example, committed his poem to paper. The modern translator looks at a printed text, and the one thing he may be confident of is that this text does not correspond to the original writing. Handwriting uses abbreviations, sometimes of generally accepted usage, sometimes personal to the writer. But even if it should correspond, there is another conclusive disproof of the notion that the form of the characters was of prime importance. One of the typical situations in which poetry was composed was at an earnest cocktail party, after sufficient spirit had been infused. Then the host might propose a topic, and ask his guests in turn to chant (orally) an extemporaneous poem on the subject. Of the great poet Po Chü-i no biography omits to mention the fact that his poems were appreciated by illiterate old women, and were constantly on the lips of fishmongers in the market-place.

What this all amounts to is simply that Chinese poetry was composed in a language, as all poetry must be. And a poem of the eighth century A.D. can be properly understood only if one knows the language of the eighth century A.D. The assumption of the "etymological" translators--Fenollosa, Pound, Ayscough, Lowell, and others--is that the meaning, connotation, allusion, perfume, concreteness of a given Chinese character has remained immutable from pre-historic times. But this is inconceivable. The important question is, "What was the word represented by a particular character in the eighth century, how did that word sound, and what were its connotations?" To discover this is the effort of philology.

Only in rare combination can philologists double as poets, or poets as philologists. The philologist is concerned with excavating expression from a foreign language, the poet with perfecting expression in his own language. The combination that succeeds is then a combination of both. Despite the trumpeting of Fenollosa to announce a new visual interpretation of Chinese poetry, there is no evidence that he ever followed his own call. The poems in Cathay, translated by Pound "from the notes of the late Ernest Fenollosa, and the decipherings of the Professors Mori and Ariga" (1915), are given a conventional interpretation. The first excursion by Pound alone is to be found in the translation of "The Great Digest" (1928, Edwards No. 36), where three pages of "Terminology" explore the possibilities of pictorial analysis divorced from accepted meaning. The results are exciting and unreal. In "The Unwobbling Pivot" (1947) a certain amount of this analysis continues, but in the "Analects" (1950) it is barely discernible. Those who take the trouble to compare this with Legge's translation (1861) will find that Pound has in large measure taken over philologist Legge and dressed up the English that was sadly unpoetic. In "The Classic Anthology" (1954) the English of Pound has loosed itself completely from any Chinese mooring. And in the Rock-Drill Cantos (1956), particularly no.85., the Chinese has become a decoration with no intelligible meaning.

To elaborate on the foregoing statements would require more space than can be allowed at present. For anyone who grants that Chinese is a language, elaboration is unnecessary. Chinese poetry, like any other, is to be sung, chanted, whispered, recited, muttered, but not (God forbid!) to be deciphered . The association of ideas that results from the dissection of a given character may produce a poetic thought. But this is a new thought, and it may completely overshadow the thought that was in the mind of the writer. In the "Terminology" prefaced to Pound's translation of "The Great Digest" a Chinese character meaning 'sincerity' is analyzed as "the precise definition of the word, pictorially the sun's lance coming to rest on the precise spot verbally." This is sheer imagination in the style of Edward Lear. What is "the sun's lance"? Even if there were an etymological basis for this fantasy, to use it in translation would be comparable to a Chinese insistence on always rendering the English word 'sincerity', as "a state of being without wax." The first line of the Analects reads, "Having studied something, constantly to practice it, is this not a joy?" Pound has "Study with the seasons winging past, is not this pleasant?" "Seasons" is impossible. The thought of "winging past" comes by isolation of a portion of the character meaning "practice". Six sentences later the same character occurs, and Pound translates it "practice". Either the thought of "winging past" failed to materialize, or it was found impossible to work it into the context. But this represents a totally irresponsible attitude toward the Chinese language. When it suits the translator's whim, he may construct any number of bright images from the bits that he thinks he has discovered in the character. When he is tired, he falls back on the simple word that the character symbolizes.

The character in this case is pronounced shyi , southern China ziq , time of Confucius zip . If there is a language, then zip has always had a specific meaning, not necessarily the same, since language grows. But this meaning cannot be found by theorizing, any more than one might determine that "minimum" means "milk" because it begins and ends in m. All Chinese literature we have, including the Analects, indicates that zip means, and has always meant, "practice". In the Analects zip occurs three times, twice in association with 'learn'. The repeated idea is that learning is fruitless unless one puts it into practice. Pound sacrifices this rather important precept for the sake of a pastoral where the seasons go winging by. Undoubtedly this is fine poetry. Undoubtedly it is bad translation. Pound has the practice, but not the learning. He is to be saluted as a poet, but not as a translator.

Copyright © 2010-2018 拼音/Pinyin.info | XHTML | CSS

What are Chinese Characters: History and Evolution of the Chinese Writing System

November 30, 2021.

This article will tackle some common questions about Chinese characters as well as their evolution.

Let’s dive in!

What are Chinese characters called?

How many chinese characters are there.

There are over 50,000 Chinese characters existing, but most Chinese dictionaries will often list less than 20,000 characters. Moreover, the Table of General Standard Chinese Characters only lists a little over 8000 characters, of which only 6,500 are designated as common.

If you are thinking about learning Chinese, do not be intimidated by the 20,000 to 50, 000 characters! According to HSK requirements, 600 words (HSK3) would be enough to “communicate in Chinese at a basic level, 2500 words (HSK5) are sufficient for reading Chinese newspapers and watching Chinese movies, and knowing 5000 words (HSK 6) would mean that you're fluent in Chinese.

Is a Chinese character the same as a word in Chinese?

Many folks who are learning Chinese may think each character represents a word. But this isn’t always true. Yes, there are individual Chinese characters that are words on their own. Some examples would be kǒu 口 (mouth), nián 年 (year), and shū 书 (book). In fact, quite a few common words are represented by just one Chinese character.

However, many words are made up of at least two Chinese characters. These characters work together to form words that are perhaps more complex or abstract. While diàn 电 means electricity, things that need electricity may require a second character, like diànnǎo 电脑 (computer).

It is indeed useful to know what individual Chinese characters mean and to be able to identify those that can stand alone. That said, it is also important to also remember that what we may consider a word in English will often require more than one character in written Chinese.

Do Chinese characters represent ideas?

No, Chinese characters do not represent ideas. Chinese characters were once believed to be ideographic. Ideographs represent ideas rather than linguistic structures. This meant that, for some time, it was believed that Chinese characters represented ideas and were not components for language and grammar.

However, as more resources were uncovered and more analyses were done, it became clear that Chinese characters are actually logographic This means that each character corresponds to one unit of language, rather than a unit of thought. So in fact, Chinese characters do not represent ideas.

The History and Evolution of Chinese Characters

The history of Chinese characters dates back thousands of years. In fact, their date of origin is still unknown. However, more than a century’s worth of work has been committed to learning more about this written language’s roots.

When were Chinese characters invented?

While it is still unknown exactly when Chinese characters were invented, a number of archaeological discoveries are helping scholars to pinpoint a date.

Some of the earliest Chinese characters date back to the Shang Dynasty (1600-1050 B.C.). They appeared on artifacts uncovered outside Anyang, the location of the last capital of the Shang Dynasty. The inscriptions of these early Chinese characters were etched into the shoulder bones of oxen, and into the plastrons (or shells) of turtles. Used by diviners to help the king make contact with the dead, these artifacts are now known as oracle bones.

It is important to note that the writing system found on these oracle bones indicate that a written language was already quite well developed at the time of inscription, suggesting that the origins of Chinese characters themselves preceded the artifacts discovered.

In fact, it is believed that by 1400 B.C. the Chinese script already had 2,500-3,000 characters, most of which still can be understood today. There also have been artifacts containing characters discovered outside of Xi’an that date back to 4800-4200 B.C., though those findings are still being researched.

Following oracle bones were collections of bronze containers, typically used as sacrificial vessels, called bronzes. On these bronzes, people would inscribe significant events like sacrifices, battle results, and so on. These artifacts date back to as early as the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.). These inscriptions continued to be used until the rise of brush and ink. From there, various forms of Chinese character scripts were born, thanks to the artistic freedom and creativity brush and ink allowed.

What were the stages and forms of Chinese character writing?

Chinese characters have changed and evolved over the years, but so too have the methods used to write them. Think of how handwriting has changed in your own language, and how it can even vary from person to person. The way folks wrote centuries ago is quite different now. The same is true for Chinese character writing. Still, the script we see now has roots in those original artifacts.

By examining this brief history of Chinese characters, we can see clear stages in the evolution of Chinese characters.

First came the jiǎgǔzì 甲骨字 (oracle bone characters). These characters, carved into bone or shell, were also often quite literal depictions of the words they described. As the language evolved, so too did the characters etched into the oracle bones.

Then came the jīnzì 金字 (metal characters). These characters and this type of script were found on the bronzes. Over the years, they evolved into zhuànshū 篆书 (seal characters), or decorative characters used on seals and signets.

Seal characters can be further sorted into two categories: dàzhuànshū 大篆书 (large seal characters), primarily used during the Zhou Dynasty (1100-256 B.C.), and xiǎozhuànshū 小篆书 (small seal characters), created during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.).

Interestingly, the small seal characters were created during the Qin emperor’s efforts to standardize Chinese characters which fell under a series of sweeping reforms intended to consolidate the empire. The reform was to standardize Chinese characters focused on the 3,000 most common characters.

This standardized form of writing helped to form the basis for modern-day script. It is interesting to note that you have likely seen examples of small seal characters today. All of its strokes were of equal thickness, and all characters were all of equal sizes. While this made small seal script impractical for everyday use, it made it a lovely script for things like engravings and seals.

From the seal scripts, we move to lìshū 隶书 (clerical script). This was the official script used during the Han Dynasty (207 B.C. - 220 A.D.). This script was simplified from the aforementioned small seal script. Looking at it today, you can see clear similarities to the scripts and styles we use today.

At roughly the same time, xíngshū 行书 (running script) and cǎoshū 草书 (grass script) arose. The running script is an example of a handwriting script, while the grass script is an example of a shorthand script. Both were used to write Chinese characters quickly. However, this made them quite illegible. Chinese language learners would likely struggle trying to read either of these scripts today.

Another script to emerge around the time of clerical script was kǎishū 楷书 (standard script). Kǎishū 楷书 arose near the end of the Han Dynasty and was very popular in subsequent centuries. This script is the script which is still in use today.

Now that we have taken a look at the styles in which Chinese characters were written throughout history, let’s take a closer look at the characters themselves and how they have evolved.

Traditional vs Simplified Chinese: What are the differences?

Traditional chinese characters are older than simplified chinese characters.

Traditional Chinese is the older version of the Chinese writing system. They were “simplified” after the 1949 Revolution mainly in the hope to make learning to read and write more accessible to the general population, which would increase literacy across the country. There were a few rounds of simplification, the first of which was done in 1956, with other rounds to follow in the 1960s-1970s. The resulting writing system is what we now know as Simplified Chinese.

Traditional and Simplified Chinese characters are used in different places

Simplified characters, jiǎntǐzì 简体字, is the writing system used in Mainland China, hence they are also what many Chinese language learners study these days. Simplified characters are also used in Singapore, Malaysia and the United Nations.

Traditional characters, fántǐzì 繁体字, are used in Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and in various areas where groups of Chinese immigrants have gathered. (You may know these areas as “Chinatowns”, where traditional characters will be used on signs, restaurant menus, printed materials, etc.)

Traditional characters tend to have more strokes than Simplified characters

While seemingly more difficult to read and write, the additional strokes in traditional Chinese characters often portray components that add historical or cultural importance to the character.

Advocates of traditional characters will argue that the simplification process eliminated useful components from the characters. These components can, in fact, aid the character-learning process, too, as they often provide clues to a character’s meaning and pronunciation.

However, thanks to the simplification process of the 1950s, most characters, now known as Simplified characters, require far fewer strokes to write and are easier to read for those new to the language.

It is important to note that not all characters have been simplified. While there are certainly traditional Chinese characters with dozens of strokes, many were already sufficiently simple in their original forms. This is why there are many shared characters between the traditional and simplified systems even though more than 2,000 characters were indeed simplified.

Are Cantonese and Mandarin written the same way?

The only exception is Taiwan, where the official spoken language is Mandarin is written in Traditional Chinese characters.

Many Chinese learners have studied simplified characters, but when were Chinese characters simplified?

When were Traditional Chinese characters simplified?

First, let’s remember that the characters found on oracle bones were often quite literal depictions of what they represented . The word for moon ( yuè 月) would have looked quite like a crescent moon, and the word for sun ( rì 日) would have looked like a sun with rays shining out.

As the written language progressed, the aforementioned logographs came into play from the bronze period onward. More complex characters developed, especially to accommodate larger and more complex vocabularies. Eventually, these characters evolved into what we know now as traditional characters ( fántǐzì 繁体字).

Now, these traditional characters may seem intimidating, as they often have far more strokes. In fact, over the centuries, folks had already been simplifying characters on their own, in notes or personal documents. However, those simplifications had never been officially recognized. The idea to officially simplify Chinese characters was introduced at the start of the 20th century by linguist Lufei Kui, and again later in the 1930s and 1940s by the Guomingdang.

Chinese characters were officially simplified to the form which we know now after the 1949 Revolution. The new government hoped to increase literacy across the country, and in turn improve the nation’s economy. To do that, the Communist Party developed a system that would make learning to read and write more accessible for hundreds of millions of people. The first round of simplified Chinese characters was released in 1956, with other rounds to follow in the 1960s-1970s.

More than 2,000 complicated characters were simplified. However, the transition was not met with unanimous acceptance. There were those - especially among revolutionaries and intellectuals - that insisted the traditional Chinese characters should continued being used. By and large though, the simplified characters played their role, seemingly helping to increase literacy rates across the country.

How were traditional Chinese characters simplified?

Let’s take a look at those categories.

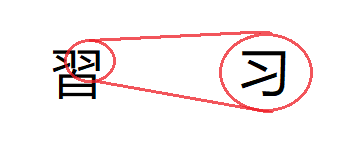

1) Characters that were components (or parts) of traditional characters.

Let’s look closer at the character xí 习 (habit). In traditional characters, this word is written as 習. At the top, you can see two of the simplified version (习) side by side. So instead of writing the entire traditional character, the simplified version is simply one of the top components. Note, though, that characters in this category may stand on their own, but they are not radicals.

2) Characters in which the left-side radicals were simplified, but the stand-alone character was not changed.

A good example of this is the word yán 言 (speech, word). The stand-alone character, 言, was not changed. However, in traditional characters, 言 would also appear as a radical on the left side of other characters, like shuō 說 (to speak). When simplified, the left-side radical becomes 讠, and the simplified character becomes 说.

3) Characters that were simplified as both stand-alone characters and as character components.

Here, a great example is jiàn 见 (view, opinion), written here in its simplified form. In traditional, this characters is written as 見. We can see that in this case, the stand-alone character was simplified. Unlike the second category above, here the same simplified form is also a component of other characters, for example in the word for xiàn meaning “cash, money”: 现 (simplified) vs. xiàn 現 (traditional).

Remember we mentioned above that folks had been simplifying characters for years before the official standardization? Well, the final consideration used when officially standardizing characters was to use those already-existing simplifications and short-hand versions. From these, the official set of simplified characters was created. For example, consider weì 卫 vs. 衛 (to defend, guard).

No matter their differences, traditional and simplified characters both serve an important purpose in unifying Chinese speakers. Chinese characters create a common medium for such a large country. No matter the dialect spoken - some of which are mutually incomprehensible - everyone uses the same written characters.

Are Traditional Chinese characters and classical Chinese the same thing?

Is hanzi and kanji the same.

For any Chinese language learner, getting the hang of reading and writing Chinese characters is a must. While it may seem intimidating, it will also further your understanding of this vibrant language, and the history and culture are interwoven with it.

Post contributed by Alexandra Sieh

Fenollosa Pound Olson and the Chinese written character

“The first was Ernest Fenollosa’s provocative essay ‘ The Chinese Wriiten Character as a Medium for Poetry .’ He found the Pound-edited text of the essay in the latter’s book Instigations and excitedly copied out its main arguments into his notebook that June. Fenollosa’s account of the exhaustion of poetic qualities in modern discourse resulting from a degeneration of the original capacity of language to mime the physical processes, and his implicit advocacy of a return to the state of primal verbal immediacy, with words once again becoming instrumental to the creation of ‘a vivid shorthand picture of the operations of nature,’ held for Olson the same appeal it had for Pound before him.–Tom Clark, Charles Olson: The Allegory of a Poet’s Life . pg. 103.

The Common App Opens Today—Here’s How To Answer Every Prompt

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Writing the Personal Statement for the Common Application