Special Education Resource Project

Explicit instruction case study part one.

What is a case study? Heale and Twycross (2018) defined a case study as “research methodology, typically seen in social and life sciences. There is no one definition of case study research. However, very simply… ‘a case study can be defined as an intensive study about a person, a group of people or a unit, which is aimed to generalize over several units’.” The case study we are about to explore for explicit teaching follows a teacher as she is restructuring her lesson plan for a phonics lesson. We will explore who this teacher is, who her students are, how she adjusts her lesson plans and how she demonstrates this during her instruction. So…let’s meet the teacher.

(Please note that this case study is not a real life example and the occurrence of names to real people is a coincidence. All materials you will see in this case study are original.)

Mrs. Adams is a resource special education teacher at a mid-sized elementary school. The school is a Title 1 school and serves a large population of English as a Second Language Learners. Mrs. Adam’s class is made up of three 1st grade students. Joey whose diagnosis is AHDH, Jordyn whose diagnosis is specific learning disability (SLD) and Oscar whose diagnosis is specific learning disability and he is an English Language Learner. Her students meet with her daily for 45 minutes for resource reading.

After attending a professional development at her school last week, Mrs. Adams wants to use the principles of explicit instruction in her lessons. She starts by choosing a lesson on the digraph -sh. This is the first time this skill will be introduced to students. The lesson will examine the digraph -sh both at the beginning and the end of words.

If you would like a copy of the 16 Elements of Explicit Instruction, please click on the link below.

Explicit Instruction – Chapter One (Archer and Hughes, 2011)

Mrs. Adams identifies the prerequisite skills that her students will need to help them with the digraph -sh. She decides to review letter sounds since digraphs are different from individual letter sounds. Mrs. Adams has already established the term “everyone” for the signal word for verbal responses. This is how she introduces the lesson:

Mrs. Adams Lesson Introduction:

“Today we are going to be learning about digraphs. Digraphs are two letters put together to make one sound. These sounds are different from our other letter sounds because those sounds only make one sound. Let’s look at the letters “s” and “h. Digraphs are an important part of being able to decode and read words.”

“We are going to be practicing with the digraph “sh.” By the end of the lesson, you will be able to find the sound “sh” at the beginning of words. Let’s start our lesson.”

“What sound does “s” make? (Presents students with S letter card)

“Everyone – “ssss.” Very good, “s” says “sss.”

“What sound does “h” make? (Presents students with H letter card) Everyone – “huh.” Good job, “h” says “huh.”

“Now let’s look at the letters “s” and “h” put together (presents students with SH letter card).

When these letters are put together, they no longer make the sounds “sss” and “huh.” When together, “s” and “h” make the sound “sshh. Watch me, I’m going to say the sound for “sh”…”ssshh.”

“Now it’s your turn. What sound does “sh” make? Everyone – “sshhh.” That’s exactly right. When “s” and “h” are together, they make the sound “sshh.”

“Let’s do some more practice.”

In the lesson, she focused her instruction on the critical content (Element #1) . She decided that the digraph “sh” was going to be the focus of the instruction. Digraphs are a central part to decoding words.

After identifying her critical content, she identified the prerequisite skills that her students would need to learn the digraph “sh” (Element #6) . Students needed to be able to identify the letters “s” and “h” and to know their sounds.

To start her lesson, Mrs. Adams began her lesson with a clear statement of purpose (Element #5) . Her students know exactly the skill they will be learning and what he expectations are for the end of the lesson.

During her introduction, she used clear and concise language. She referred to “sh” a digraph. This is the terminology used to describe the sounds sh, ch, th, wh, etc. She also refers the letters as having sounds. (Element #8)

Mrs. Adams provided opportunities for her students to respond to the letter sounds (Element #11) .

Let’s visit Case Study Part 2 to see how Mrs. Adams continues using the elements of explicit instruction in her lesson.

Click on the image below to see Case Study Part 2.

References:

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching . New York: Guilford Press.

Discover scientific knowledge and stay connected to the world of science

Discover research.

Access over 160 million publication pages and stay up to date with what's happening in your field.

Connect with your scientific community

Share your research, collaborate with your peers, and get the support you need to advance your career.

Visit Topic Pages

Measure your impact.

Get in-depth stats on who's been reading your work and keep track of your citations.

Advance your research and join a community of 25 million scientists

Researchgate business solutions.

Scientific Recruitment

Marketing Solutions

America's Education News Source

Copyright 2024 The 74 Media, Inc

- EDlection 2024

- Hope Rises in Pine Bluff

- Artificial Intelligence

- science of reading

Researchers: Higher Special Education Funding Not Tied to Better Outcomes

Early look at state-by-state spending on special ed reveals scattershot efforts, suggests evidence-backed reading instruction for all kids is crucial..

Sharpen Up!

Sign up for our free newsletter and start your day with in-depth reporting on the latest topics in education.

74 Million Reasons to Give

Support The 74’s year-end campaign with a tax-exempt donation and invest in our future.

Most Popular

Meet america's high schoolers vying for olympic gold, lessons for closing schools: face the challenge, prioritize students, be honest, ohio moves ahead with science of reading lessons, but some schools still lag, the key investors who once touted l.a. schools’ failed $6m ai chatbot go silent.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

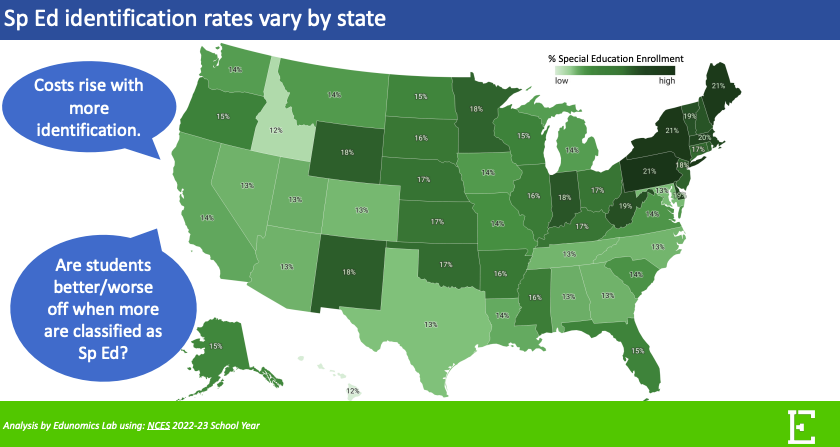

An early look at new special education datasets reveals massive inconsistencies in how many children states are identifying as needing services, how much is being spent on them and whether that funding is tied to better outcomes, according to Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab.

Preliminary though the research is, even the broad takeaways are especially timely, Roza recently told a group of policymakers, educators and journalists. The number of students with disabilities has risen dramatically over the last decade, as has the share of school budgets dedicated to paying for special education.

“Historically, our tendency has been to look the other way on special ed spending,” she said . “It hasn’t gotten the same scrutiny [as] other elements in the district budget.”

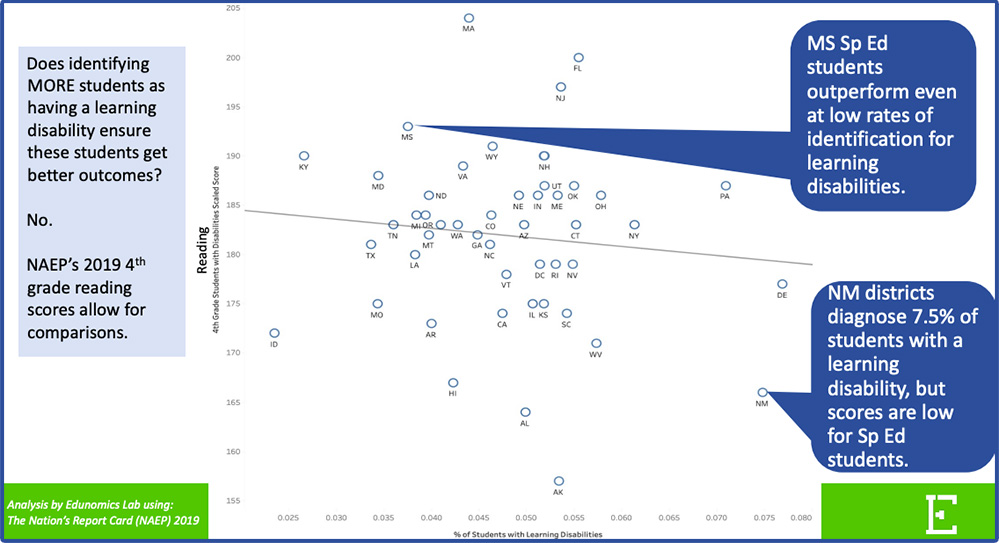

One immediate takeaway is that states that provide sound literacy instruction for all students also post better reading scores for special education students, Roza noted. Case in point: Mississippi, where recent, dramatic gains in literacy have been credited to a 10-year push by state officials to ensure evidence-based reading instruction is taking place in every classroom.

Mississippi is one of two states that dedicated the smallest portion of its education budget — some 8% — to meeting the needs of special education students, yet it is one of four where children with disabilities perform the highest on the reading portion of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

By contrast, Connecticut spends nearly 22% of its education budget on special education but has middle-of-the-pack reading performance among students with disabilities. More than half of the state’s third graders are reading below grade level, and a new law requiring science-based literacy instruction will not be fully implemented until 2025.

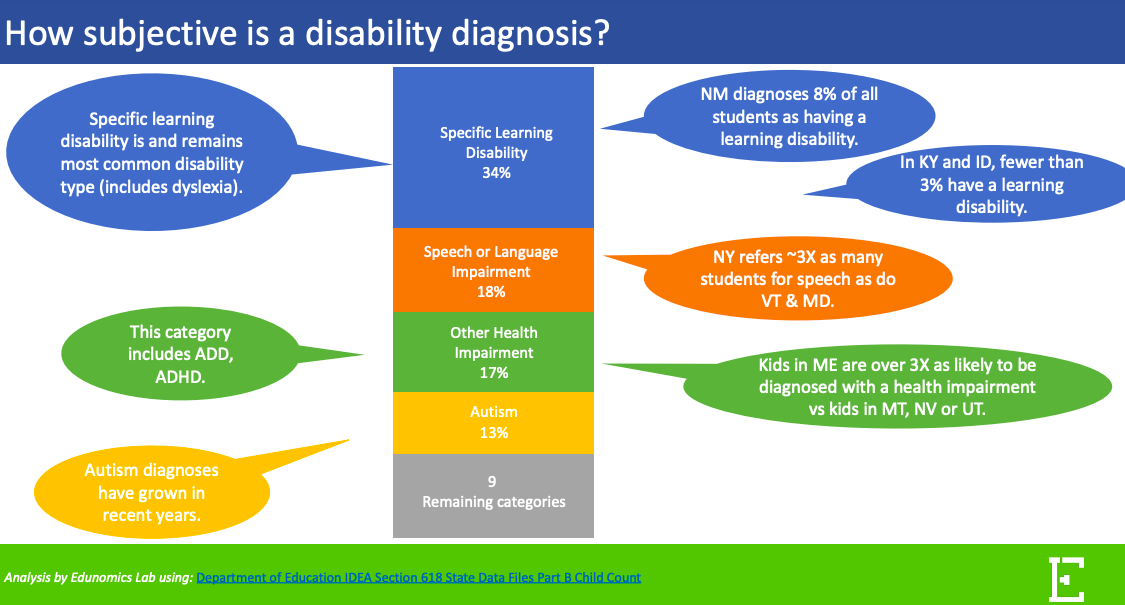

This finding is particularly important because the most common special education diagnosis, specific learning disability, includes children who are dyslexic or who have other neurological differences that interfere with their ability to process language or do math. More than a third of students receiving services fall into this category.

High-quality core literacy instruction could mean fewer students who need an individualized education program — a federally mandated plan that spells out how a child with a disability will be served. Other research has shown that struggling readers whose needs are identified early are less likely to need intensive support in later grades.

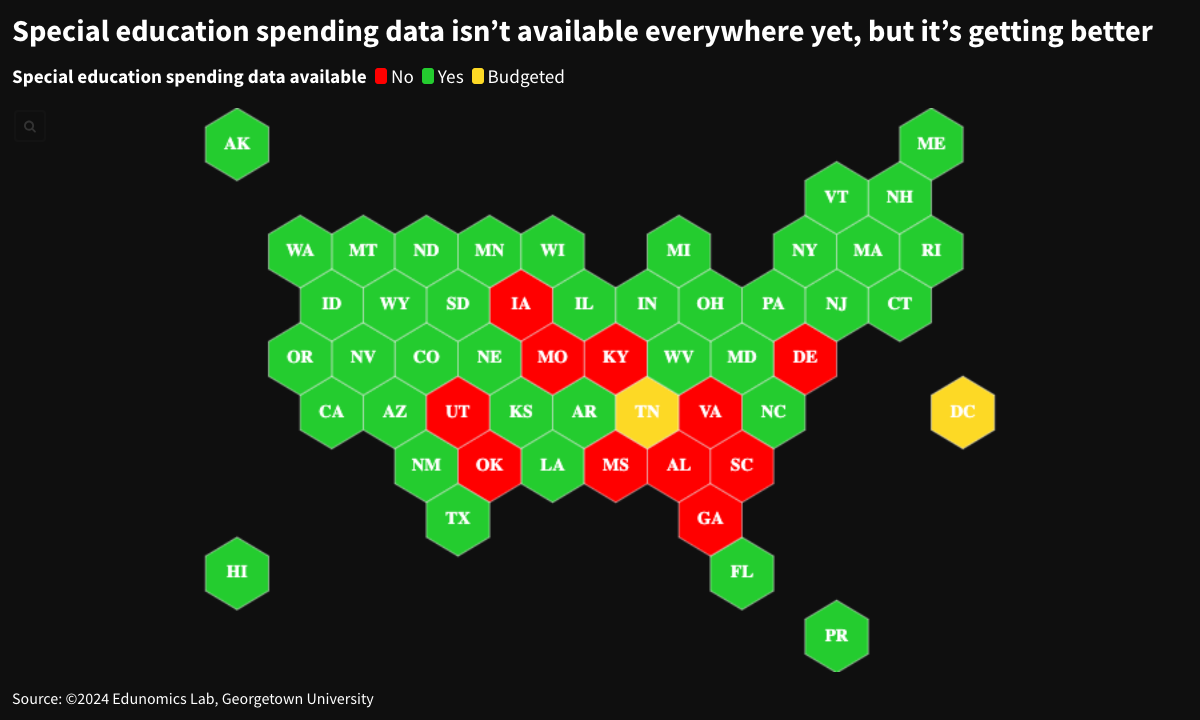

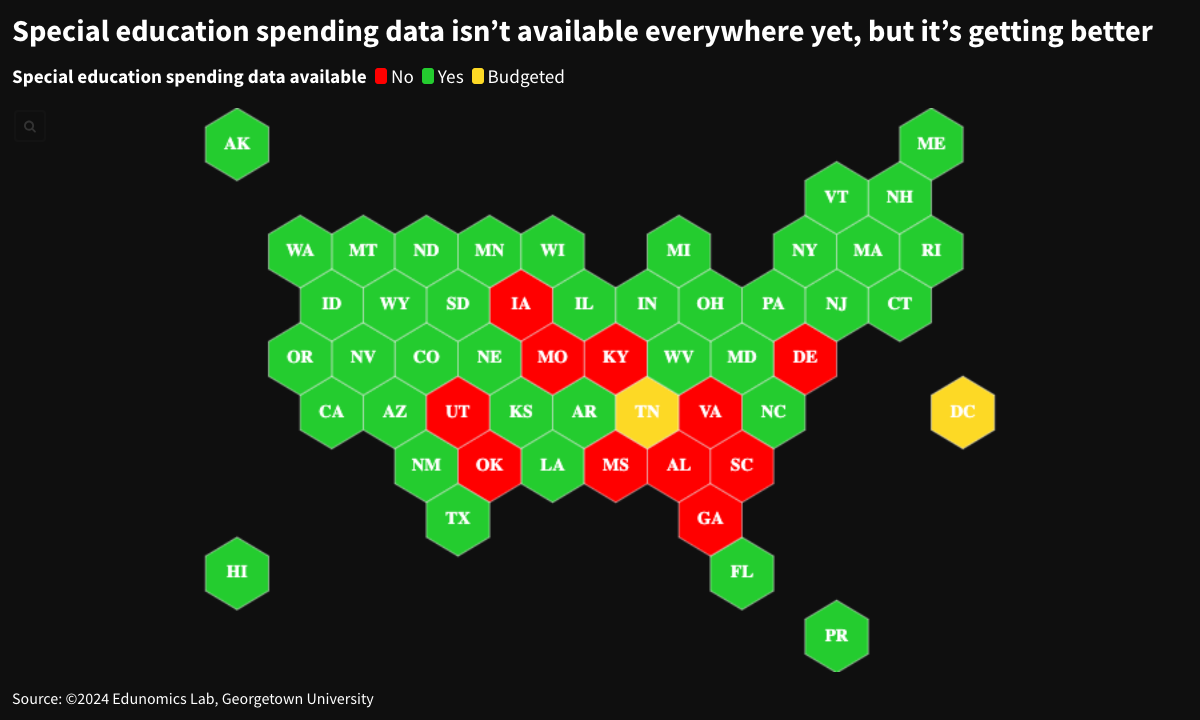

In the 2019-20 school year, the National Center for Education Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm, began collecting data compiled by states on district-level special education spending. A number of states have yet to provide any information, but Edunomics researchers were able to combine the first two years of information with existing records to begin building an overview.

Between the 2013-14 and 2022-23 school years, the number of children in special education rose from 6.5 million to 7.5 million, even as public school enrollment fell by more than 400,000. In four Northeastern states — New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Maine — 1 in 5 students now have an individualized education program, or IEP, while in 11 states, 13% or fewer receive services.

From state to state, diagnoses are wildly inconsistent, raising questions about the subjectivity of how students are funneled into special ed. New Mexico, for example, diagnoses specific learning disabilities in 8% of students, versus less than 3% in Kentucky and Idaho. However, despite identifying a high number of children with learning disorders, New Mexico has some of the lowest literacy rates among special education students in the country.

New York refers almost three times as many children for speech and language services as Vermont and Maryland. Students in Maine are more than three times as likely to be categorized as “other health impairment” — a diagnosis category that includes ADHD — as pupils in Montana, Nevada and Utah.

States also vary wildly in how many special education staffers schools employ, with Ohio and Idaho having less than 20 per 200 students. Hawaii, New York and New Hampshire have three times as many. Yet Hawaii significantly underperforms national averages.

The data also raise questions about the quality of staff delivering services and inequities in how teachers are assigned to schools. Since 2007, the number of special education teachers has risen by 12%, while the number of specialists and paraprofessionals has jumped by 35% and 37%, respectively.

One reason higher staffing levels don’t necessarily correlate to better student outcomes could be that instruction is being delivered by paraprofessionals — often low-skilled, entry-level staff — and not special education teachers.

The data also suggest that the perennial shortage of special educators contributes to inequities in which kids get the most qualified instructors. In Massachusetts — which Edunomics researchers praised for its unusually transparent spending reports — low-poverty schools have higher numbers of licensed special educators. High-poverty schools have fewer teachers and far more paraprofessionals.

Districts often cite federal maintenance-of-effort laws, which put strict guardrails on attempts to lower special education spending, as a reason why they don’t scrutinize the cost-effectiveness of their services. While some of these assumptions are incorrect, more legal flexibility would help, said Roza.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to Edunomics Lab and The 74 .

Beth Hawkins is a senior writer and national correspondent at The 74.

- reading instruction

- school funding

- special education

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74's republishing terms.

By Beth Hawkins

This story first appeared at The 74 , a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

On The 74 Today

AI’s Potential in Special Education: What Teachers and Parents Think

- Share article

Educators and parents of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities are optimistic about artificial intelligence’s potential to create more inclusive classrooms and close educational gaps between students with disabilities and those without, concludes a report from the Special Olympics Global Center for Inclusion in Education .

However, both groups are also concerned about the possibility that AI use in schools could decrease human interaction and that schools with fewer resources could be left behind, the report found.

The findings, released July 22, are based on a survey of 500 U.S. parents of children with intellectual or developmental disabilities, as well as 200 U.S. K-12 teachers, conducted by Stratalys Research between June 3-10.

Ever since generative AI technology broke into K-12, some special education practitioners have experimented with using it to speed up some of their administrative tasks.

But experts say there still isn’t enough data on how using generative AI for instruction could affect students with disabilities, and educators should approach the technology with caution.

Most datasets that AI tools are trained on contain a lot of information about neurotypical students, but they don’t have nearly as much to draw from on students in special education , which could translate into technology that isn’t as helpful for those populations.

Indeed, a majority of educators (66 percent) and more than a third of parents (35 percent) say they don’t believe or are not sure if AI developers are taking the needs and priorities of students with disabilities into consideration, according to the report.

Many teachers and parents think AI will make education more inclusive

Still, most parents and teachers have positive views about the emerging technology: More than 7 in 10 parents and 6 in 10 teachers say AI will make education more inclusive, the report found. Additionally, more than 7 in 10 parents also believe AI has the potential to close educational gaps between students with and without disabilities, and a smaller majority of educators (54 percent) say the same.

The report found that a plurality of parents and teachers believe that AI’s potential to create more adaptive, personalized learning and its potential to help students write and express themselves could have a “major positive impact” on students with disabilities.

The report “reflects the optimism of the parents,” said Margaret Vice, the managing director of FGS Global’s research division, a consulting firm that collaborated with the Special Olympics Global Center for Inclusion in Education on the report. Parents are “eager for anything to help their child grow and learn.”

Teachers, however, are a little bit more skeptical , Vice said.

“Their experience is likely rife with new tech forced upon them, and new ways of teaching, new ideas, new things to learn, without, maybe, the training and the time and the resources put toward allowing them to do that,” she said.

AI shouldn’t ‘replace relationships’

Special education experts are optimistic about AI’s potential to create better and more personalized learning experiences for students, too, but they’re also cautious considering the technology is still so new.

“My concern is that [AI] doesn’t replace the relationships,” said Luis Perez, the disability and digital inclusion lead for CAST, a nonprofit that advocates for universally accessible educational materials. “We don’t want to plop a student in front of a computer and have [the kid] just interact with a ‘personalized system.’ There’s a lot more to learning than access to information. I just want to be cautious that when we say personalized, we’re not taking out the human element of what an education for individuals with intellectual disabilities and all students with disabilities should have.”

A decrease in human interaction is also the top concern of parents and teachers when it comes to increasing the use of AI in schools, according to the report. However, parents are less likely to be concerned about AI’s potential negative impacts than teachers.

AI literacy will be critical to counter the concerns that parents, teachers, and experts have, Perez said.

“Students, when they move into the workforce, they’re going to encounter AI,” he said. It’s important that “people understand what AI is, what it can do, what its potential is, but also its limitations, so you have a balanced perspective on it.”

AI literacy is important for educators and parents, too, experts say. Some educators are already getting professional development on the technology , but it’s unclear how much parents know about AI. As schools experiment with these AI tools, experts say they should bring parents along and let them explore and learn alongside educators and students.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Factors Maintaining EFL Learners’ Directed Motivational Currents in Learning English: An Activity-Theory-Informed Multiple Case Study

維持 EFL 學習者英語學習定向動機流之因素:活動理論下的多個案研究

- Original Paper

- Published: 08 August 2024

Cite this article

- Mohammad N. Karimi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7834-6368 1 &

- Zohreh Parsamajd 1

Although research on directed motivational currents (DMCs) in second/foreign language learning has grown exponentially, a systematic analysis of the factors influencing English as a foreign language (EFL) learners’ DMCs in learning English is lacking in the literature. In this light, through an activity theoretic lens, this study explored factors which trigger/maintain pre-intermediate EFL learners’ DMCs. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews and diary reports and analyzed using NVivo 12. The findings were then mapped onto the six key elements of activity theory (AT). The results revealed how four factors—namely classmates, teachers, family, classroom regulations and rules—influenced the participants’ DMCs. In addition, learners’ DMCs were shown to be mediated by tools—including the knowledge gained from English books; English motivational movies, songs, and motivational quotes; exams; technology; attention, and care received through social relations—and community membership. The results highlight the importance of considering the broader contexts of language learning when designing instructional interventions.

儘管第二語言/外語學習中定向動機流 (DMCs) 的研究急遽增加,但文獻中缺乏關於影響EFL學習者的英語學習定向流因素的系統性分析。有鑑於此,本研究透過活動理論的角度,探討了引發/維持初中級學習者DMC的因素。本研究透過半結構式訪談和日記來搜集數據,並使用NVivo 12 進行分析。然後將研究結果映射到活動理論(AT)的六個關鍵要素。研究結果顯示,四個因素是如何影響受試者的DMCs,即同學、教師、家庭和課堂常規。此外,學習者的DMC還受到一些工具的影響,其中包含了從英語書籍中獲得的知識、英語勵志電影、歌曲和勵志名言、考試、科技、透過社群關係所得到的關心與照顧和社群成員的身份。這些研究結果凸顯了在設計教學干預時,考量更廣泛的語言背景之重要性。

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Chen, K. C., & Jang, S. J. (2010). Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (4), 74–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.01.011

Article Google Scholar

Cole, M., & Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 1–46). Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Cole, M., & Scribner, S. (1974). Culture & thought: A psychological introduction . John Wiley & Sons.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). Introduction. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I. S. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness (pp. 3–14). Cambridge University Press

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11 (4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deslandes, R., & Bertrand, R. (2005). Motivation of parent involvement in secondary-level schooling. The Journal of Educational Research, 98 (3), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.98.3.164-175

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivation strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies . Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Chan, L. (2013). Motivation and vision: An analysis of future L2 self-images, sensory styles, and imagery capacity across two target languages. Language Learning, 63 (3), 437–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12005

Dörnyei, Z., & Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating learners, motivating teachers: Building vision in the language classroom . Cambridge University Press (CUP).

Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & Muir, C. (2016). Motivational currents in language learning: Frameworks for focused interventions . Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., Muir, C., & Ibrahim, Z. (2014). Directed motivational currents: Energising language learning by creating intense motivational pathways. In D. Lasagabaster, A. Doiz, & J. M. Sierra (Eds.), Motivation and foreign language learning: From theory to practice (pp. 9–29). John Benjamins Publishing.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Ebadijalal, M., & Moradkhani, S. (2022). Understanding EFL teachers’ wellbeing: An activity theoretic perspective. Language Teaching Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221125558

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research . Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamak (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 19–38). Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14 (1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080123238

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamäki, R.-L. (1999). Perspectives on activity theory . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review, 5 (1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

García-Pinar, A. (2020). Group directed motivational currents: Transporting undergraduates toward highly valued end goals. The Language Learning Journal, 50 (5), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2020.1858144

Gardner, R. C. (2010). Motivation and second language acquisition: The socio-educational model (Vol. 10) . Peter Lang.

Henry, A. (2019). Directed motivational currents: Extending the theory of L2 Vision. In M. Lamb, K. Csizér, A. Henry, & S. Ryan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning (pp. 139–161). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Henry, A., Davydenko, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 99 (2), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12214

Ibrahim, Z. (2016). Affect in directed motivational currents: Positive emotionality in long-term L2 engagement. In P. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen & S. Mercer (Ed.), Positive Psychology in SLA (pp. 258–281). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360-012

Ibrahim, Z., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2019). Shared, sustained flow: Triggering motivation with collaborative projects. ELT Journal, 73 (1), 51–60.

Jahedizadeh, S., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2021). Directed motivational currents: A systematic review. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 11 (4), 517–541. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.4.3

Karimi, M. N., & Mofidi, M. (2019). L2 Teacher identity development: An activity theoretic perspective. System, 81 , 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.006

Kuutti, K. (1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In B. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction (pp. 17–44). MIT Press.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality . Prentice-Hall.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1981). The problem of activity in psychology (J. Wertsch, Trans.). In Wertsch, J. (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 37–71). M.E. Sharpe.

MacIntyre, P., Baker, S., Clément, R., & Donovan, L. (2003). Talking in order to learn: Willingness to communicate and intensive language programs. Canadian Modern Language Review, 59 (4), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.59.4.589

Miettinen, R. (2001). Artifact mediation in Dewey and in cultural-historical activity theory. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 8 (4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0804_03

Muir, C. (2016). The dynamics of intense long-term motivation in language learning: Directed motivational currents in theory and practice. [PhD. thesis]. The University of Nottingham.

Muir, C., & Dörnyei, Z. (2013). Directed motivational currents: Using vision to create effective motivational pathways. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3 (3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2013.3.3.3

Peng, Z., & Phakiti, A. (2020). What a directed motivational current is to language teachers. RELC Journal, 53 (1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220905376

Safdari, S., & Maftoon, P. (2017). The rise and fall of directed motivational currents: A case study. The Journal of Language Learning and Teaching, 7 (1), 43–54.

Sak, M. (2019). Contextual factors that enhance and impair directed motivational currents in instructed L2 classroom settings. Novitas-ROYAL (research on Youth and Language), 13 (2), 155–174.

Sannino, A., Daniels, H., & Gutiérrez, K. (2009). Activity theory between historical engagement and future-making practice. In A. Sannino, H. Daniels, & K. D. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Learning and expanding with activity theory (pp. 1–18). Cambridge University Press.

Swain, M. (2013). The inseparability of cognition and emotion in second language learning. Language Teaching, 46 (2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

Ushioda, E. (2011). Language learning motivation, self and identity: Current theoretical perspectives. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24 (3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.538701

Ushioda, E., & Dörnyei, Z. (2012). Motivation. In S. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 396–409). Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Xodabande, I., & Babaii, E. (2021). Directed motivational currents (DMCs) in self-directed language learning: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Journal of Language and Education, 73 (27), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2021.12856

Zarrinabadi, N., Ketabi, S., & Tavakoli, M. (2019). Directed motivational currents in L2: Exploring the effects on self and communication . Springer International Publishing.

Zarrinabadi, N., & Khodarahmi, E. (2024). Some antecedents of directed motivational currents in a foreign language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 45 (4), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1931250

Zarrinabadi, N., & Soleimani, M. (2022). Directed motivational currents in second language: Investigating the effects of positive and negative feedback on energy investment and goal commitment. RELC Journal , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882221130172

Zarrinabadi, N., & Tavakoli, M. (2017). Exploring motivational surges among Iranian EFL teacher trainees: Directed motivational currents in focus. TESOL Quarterly, 51 (1), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.332

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Foreign Languages, Kharazmi University, No. 43. South Mofatteh Ave, Tehran, 15719-14911, Iran

Mohammad N. Karimi & Zohreh Parsamajd

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad N. Karimi, Zohreh Parsamajd; data collection: Zohreh Parsamajd; writing—original draft preparation: Zohreh Parsamajd; writing—review and editing: Mohammad N. Karimi; supervision: Mohammad N. Karimi. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohammad N. Karimi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Permission from relevant authorities in the institute was obtained through explaining the purpose of the study and how it would benefit the participants and the broader field of research. Considering the age range of the participants, informed consents from the parents were also obtained. In this regard, the purpose of the study, the procedures involved, and any potential risks or benefits were explained. The participants’ consents were obtained to ensure that they understood the nature of the study and were willing to participate. Moreover, to protect the confidentiality of the participants, they were ensured that only authorized personnel had access to the data. Finally, to build trust and rapport, each participant was given a short story book as a gift at the end of the process.

Semi-structured Interview Questions.

Part One – Identifying Individual DMCs in Participants.

Goal/Vision-orientedness.

1.Would you please tell me about your motivational experience?

2.What do you want to achieve that you feel motivated for? What is your final goal?

Do you sometimes imagine yourself achieving your final goal?

Salient Facilitative Structure.

When did you first feel that you have this high/intense motivation?

Do you remember what exactly triggered your motivation? Was is a particular person or event?

Did you make any changes in your daily routines or study plan to achieve your goal?

Do you have a daily schedule? If so, what/how is it?

Did your strong motivational feeling start to lessen or are you still experiencing it?

Positive Emotionality.

How is your feeling inside about your goal?

How do you feel when you do the tasks in your schedule?

Do you enjoy doing the tasks even if they are tiring or hard?

What keeps your motivation alive?

Diary Report Instructions.

Explain the main factors that increase your motivation to learn English.

Write about the individuals who impact your motivation to learn English.

Describe any interactions you have with your classmates that influences your motivation to learn English.

Note down any support or encouragement you receive from your teachers in relation to learning English.

How has your family’s support impacted your motivation to learn English? Provide examples if possible.

Write about any rules or regulations in class and how they affect your motivation.

Note down any tools or resources which influence your motivation in learning English.

How has the diversity among English learners in your community impacted your motivation to learn English?

The Brief Description of DMCs Sent to Teachers to Help Identify DMC Cases.

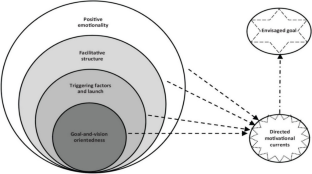

Directed motivational currents (DMC) is defined as a “prolonged process of engagement in a series of tasks which are rewarding because they transport the individual towards a highly valued goal” (Dörnyei et al., 2016 ). DMC describes those periods of sustained and heightened motivation a person can experience while engaging in a sequence of tasks related to language learning such as watching an English movie, reading a grammar book, and going to an English class. Second language (L2) learners experience DMC when they find themselves absorbed in a series of tasks, devoting considerable amount of time and energy, and feeling satisfied and fulfilled. Each DMC experience is marked by three main features: goal/vision-orientedness, a salient facilitative structure, and positive emotionality (Henry et al., 2015 ).

In this framework, a DMC experience is goal/vision-oriented in that it always moves toward a clearly defined target goal or vision, such as high proficiency in English or learning English to migrate. DMC is distinguished from other motivating practices such as hobbies which do not pursue a clearly defined goal, but are practiced for merely enjoyment. On the other hand, in DMC, the presence of a goal or vision is a key factor in constructing and sustaining DMCs. For second language learners caught up in DMCs, using the language with ease and fluency might constitute their vision. It forms a part of their identity and permeates all their actions and behaviors.

A salient facilitative structure is the second main characteristic of a DMC. DMC structure creates opportunities for feedback and progress checks and keeping the motivational currents. There are three key elements which lend this distinctive structure to the DMC: (a) a set of recurring behavioral routines suggesting that the individual caught up in a DMC executes each step without volitional control; (b) a distinguishable start and end point, meaning that the individual can easily identify the start and end of his/her motivational experience; and (c) regular progress checks where the long-term progression is divided into a number of sub-goals. These sub-goals’ accomplishment provides affirmative feedback.

The third characteristic of a DMC is positive emotionality, meaning that individuals engaged in a DMC show a deep feeling of pleasure which is entirely different from the short-lived sensation of happiness experienced through mundane fun activities. A goal/vision a learner aspires to achieve is meaningful and deeply linked to his or her identity and any attempt to accomplish the goal generates a profound feeling of enjoyment (Henry et al., 2015 ).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Karimi, M.N., Parsamajd, Z. Factors Maintaining EFL Learners’ Directed Motivational Currents in Learning English: An Activity-Theory-Informed Multiple Case Study. English Teaching & Learning (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-024-00185-w

Download citation

Received : 31 August 2023

Revised : 21 June 2024

Accepted : 26 June 2024

Published : 08 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-024-00185-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Directed motivational currents (DMCs)

- Activity theory (AT)

- Pre-intermediate EFL learners

- Learning English

- 定向動機流(DMCs)

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Newsletters

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Researchers: Higher Special Education Funding Not Tied to Better Outcomes

An early look at new special education datasets reveals massive inconsistencies in how many children states are identifying as needing services, how much is being spent on them and whether that funding is tied to better outcomes, according to Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab.

Preliminary though the research is, even the broad takeaways are especially timely, Roza recently told a group of policymakers, educators and journalists. The number of students with disabilities has risen dramatically over the last decade, as has the share of school budgets dedicated to paying for special education.

“Historically, our tendency has been to look the other way on special ed spending,” she said . “It hasn’t gotten the same scrutiny [as] other elements in the district budget.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

One immediate takeaway is that states that provide sound literacy instruction for all students also post better reading scores for special education students, Roza noted. Case in point: Mississippi, where recent, dramatic gains in literacy have been credited to a 10-year push by state officials to ensure evidence-based reading instruction is taking place in every classroom.

Mississippi is one of two states that dedicated the smallest portion of its education budget — some 8% — to meeting the needs of special education students, yet it is one of four where children with disabilities perform the highest on the reading portion of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

By contrast, Connecticut spends nearly 22% of its education budget on special education but has middle-of-the-pack reading performance among students with disabilities. More than half of the state’s third graders are reading below grade level, and a new law requiring science-based literacy instruction will not be fully implemented until 2025.

This finding is particularly important because the most common special education diagnosis, specific learning disability, includes children who are dyslexic or who have other neurological differences that interfere with their ability to process language or do math. More than a third of students receiving services fall into this category.

High-quality core literacy instruction could mean fewer students who need an individualized education program — a federally mandated plan that spells out how a child with a disability will be served. Other research has shown that struggling readers whose needs are identified early are less likely to need intensive support in later grades.

In the 2019-20 school year, the National Center for Education Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm, began collecting data compiled by states on district-level special education spending. A number of states have yet to provide any information, but Edunomics researchers were able to combine the first two years of information with existing records to begin building an overview.

Between the 2013-14 and 2022-23 school years, the number of children in special education rose from 6.5 million to 7.5 million, even as public school enrollment fell by more than 400,000. In four Northeastern states — New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Maine — 1 in 5 students now have an individualized education program, or IEP, while in 11 states, 13% or fewer receive services.

Washington State Schools Missed 8,500 Kids for Special Ed Referrals During COVID

From state to state, diagnoses are wildly inconsistent, raising questions about the subjectivity of how students are funneled into special ed. New Mexico, for example, diagnoses specific learning disabilities in 8% of students, versus less than 3% in Kentucky and Idaho. However, despite identifying a high number of children with learning disorders, New Mexico has some of the lowest literacy rates among special education students in the country.

New York refers almost three times as many children for speech and language services as Vermont and Maryland. Students in Maine are more than three times as likely to be categorized as “other health impairment” — a diagnosis category that includes ADHD — as pupils in Montana, Nevada and Utah.

States also vary wildly in how many special education staffers schools employ, with Ohio and Idaho having less than 20 per 200 students. Hawaii, New York and New Hampshire have three times as many. Yet Hawaii significantly underperforms national averages.

The data also raise questions about the quality of staff delivering services and inequities in how teachers are assigned to schools. Since 2007, the number of special education teachers has risen by 12%, while the number of specialists and paraprofessionals has jumped by 35% and 37%, respectively.

One reason higher staffing levels don’t necessarily correlate to better student outcomes could be that instruction is being delivered by paraprofessionals — often low-skilled, entry-level staff — and not special education teachers.

Desperate to Hire Special Ed Teachers? Try Looking in Regular Ed Classrooms

The data also suggest that the perennial shortage of special educators contributes to inequities in which kids get the most qualified instructors. In Massachusetts — which Edunomics researchers praised for its unusually transparent spending reports — low-poverty schools have higher numbers of licensed special educators. High-poverty schools have fewer teachers and far more paraprofessionals.

Districts often cite federal maintenance-of-effort laws, which put strict guardrails on attempts to lower special education spending, as a reason why they don’t scrutinize the cost-effectiveness of their services. While some of these assumptions are incorrect, more legal flexibility would help, said Roza.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to Edunomics Lab and The 74 .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

fail the needs of special education students. A case study is a reliable way of conducting research in an education setting especially in special education. It has been used effectively acknowledging and assessing the needs of students in education. A case study is the best methodology when holistic, in-depth research is needed.

The Journal of Special Education (JSE) publishes reports of research and scholarly reviews on improving education and services for individuals with disabilities. Before submitting your manuscript, please read and adhere to the author … | View full journal description. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

friend, the school's special education teacher. She asked the teacher to informally observe Gabe in her classroom the next time she had a few hours. Having briefly seen Gabe in motion on the playground, the special education teacher readily agreed. In the meantime, the special education teacher suggested that Susan collect informal

SCDs have been important for special education research since their inception, and they remain both frequently used and necessary for accumulating evidence in the field (e.g., 83% of studies assessing interventions for individuals with autism use SCDs; Steinbrenner et al., 2020).

(Tannock, 2009) in order for both general education students and special education students to achieve their full potentials in a classroom run by two teachers. Special education inclusion services differ greatly by school, by town, and by state. A special education inclusion teacher can be in a classroom and work as a helper, or the special

A case study is one of the most commonly used methodologies of social research. This article attempts to look into the various dimensions of a case study research strategy, the different epistemological strands which determine the particular case study type and approach adopted in the field, discusses the factors which can enhance the effectiveness of a case study research, and the debate ...

INTRODUCTION. Special schools and special classes for pupils with special education needs (SEN) are part of the educational systems in most countries; they exist more or less in parallel to regular schools (EADSNE, 2013) and cater for a relatively large number of pupils.According to statistics (EASNIE, 2020), a total average of 1.41 per cent of pupils in Europe were educated in special ...

We describe three sample research studies to illustrate mixed-methods designs and contributions. ... case, or research session may be collected and analyzed or a single source of data may be analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative analyses. Explore a broad research topic (e.g., inclusive education) by collecting and combining different ...

Single-case research methods provide the basis for evaluating effective instructional approaches in special education. The purpose of this article is to provide special educators an overview of single-case research methods, with an emphasis on how these designs are used to establish whether an instructional practice relates to improved learner outcomes.

The case study research design was used with the purpose of exploring the students' perceptions of "what they learn about inclusive education during their participation in MASIE." The strength of the case study approach is the possibility to go deeper into the students' understanding of the phenomena (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Yin, 2003).

Single-Case Experimental Research: A Methodology for Establishing Evidence-Based Practice in Special Education Faisl Alqraini, Department of Special Education, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia Abstract In the field of special education there is a dearth of group experimental studies that establish evidence-based practice.

Email: [email protected]. of SCDs is aligned well with the goals of edu-cation in general and special education in par-ticular (Repp & Lloyd, 1980). Despite wide use, agencies and researchers have often excluded SCD research evidence from sys-tematic reviews due to dif culty quantifying. fi.

Employing a case study research design, this study aims to further understanding as to how inclusion is achieved in the context of the Swedish preschool for children with attachment difficulties/an attachment disorder. The rationale is to provide an answer to the key question. ... International Journal of Special Education 30 (3): 3-16 ...

This study was designed as a qualitative case study research. It involved mathematics teacher, assistant teacher, student, and parents. Data were obtained through observations and interviews. The autistic student's attitude and behaviors during mathematics learning ... this study have a special education undergraduate qualification, with 11 ...

Explicit Instruction Case Study Part One. What is a case study? Heale and Twycross (2018) defined a case study as "research methodology, typically seen in social and life sciences. There is no one definition of case study research. However, very simply… 'a case study can be defined as an intensive study about a person, a group of people or a unit,...

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the current situation of providing remote special education during COVID-19. Special education refers to a range of educational and social services provided by the public school system and other educational institutions to individuals with disabilities. To the best of our knowledge, no study was ...

The study contributes to a deepened understanding of the complexity of education for pupils with ID in segregated settings. Discover the world's research 25+ million members

Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan, 9, 1-6. Citations (0) References (41) ... Special education teachers should prepare themselves with various knowledge, expertise and skills to ...

Two educational trends that have had major impacts on school policies of the last few decades are inclusive education and digitalisation. To that end, the purpose of this study is to examine how inclusive education and the digitalisation of education are related, understood, and represented in one case of Swedish special education practice. Using activity theory as a theoretical framework, the ...

Within the existing legal framework of the Russian Federation, any child with a disability can study in an ungraded school, which obligates the school to create special learning conditions for the child: an adapted educational program, remedial support, an accessible environment, and special textbooks and teaching aids.

CASE STUDY: Kenny. Present Levels of Performance (Reading, Math, Communication, Social Skills, Motor Skills, etc. . .) Reading: Vocabulary 9.0 Comprehension 10.0. Written Language: Passed state assessment test at proficiency level. Math: Passed state assessment test at the advanced proficiency level. Goals for Future Growth.

The key features of special education in the apartheid years were racially segregated education departments and schools; unequal resourcing that favoured white children (in special or ordinary schools); categorisation of children based on disability type, underpinned by the 'science' of orthopedagogics; and the rigid distinction between ...

Lysandra Cook is an Associate Professor in the Special Education Program at the University of Virginia School of Education and Human Development, and received her PhD from Kent State University. Her scholarly interests revolve around translating research to practice in special education, including (a) identifying and implementing evidence-based practices, (b) supporting pre- and in-service ...

Keywords: Inclusion, Inclusive Education, Special Education, Russia 1. Theoretical Perspective Integration of children with special needs in educational institutions is a logical stage in the development of special inclusive education in any country of the world. It is the process that involves all advanced countries, including Russia.

The sample of this study is represented by 313 respondents (mean age 33.6±13.9; men — 9.6%, women — 90.4%), including 41 students of secondary vocational education organizations, and 272 ...

By contrast, Connecticut spends nearly 22% of its education budget on special education but has middle-of-the-pack reading performance among students with disabilities. More than half of the state's third graders are reading below grade level, and a new law requiring science-based literacy instruction will not be fully implemented until 2025.

Special education teacher Chris Simley, left, places a coffee order at a table staffed by student Jon Hahn, volunteer Phil Tegeler, student Brianna Dewater, and student Mykala Robinson at Common ...

Although research on directed motivational currents (DMCs) in second/foreign language learning has grown exponentially, a systematic analysis of the factors influencing English as a foreign language (EFL) learners' DMCs in learning English is lacking in the literature. In this light, through an activity theoretic lens, this study explored factors which trigger/maintain pre-intermediate EFL ...

The general purpose of this study is to determine the issues and challenges of special education (SPED) teachers in teaching children with learning disabilities in the City Division of Ilagan Isabela, Philippines. The 15 SPED teachers were served as the respondents of this study using purposive sampling technique. Qualitative Research

In the 2019-20 school year, the National Center for Education Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Education's research arm, began collecting data compiled by states on district-level ...