- International

- Business & Industry

- MyUNB Intranet

- Activate your IT Services

- Give to UNB

- Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning

- Teaching & Learning Services

- Teaching Tips

- Instructional Methods

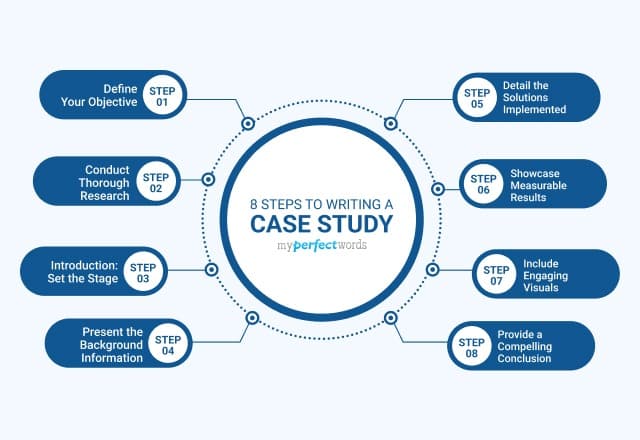

- Creating Effective Scenarios, Case Studies and Role Plays

Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays

Printable Version (PDF)

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course. See Research Findings on University Teaching Methods .

Typically you would use case studies, scenarios and role plays for higher-level learning outcomes that require application, synthesis, and evaluation (see Writing Outcomes or Learning Objectives ; scroll down to the table).

The point is to increase student interest and involvement, and have them practice application by making choices and receive feedback on them, and refine their understanding of concepts and practice in your discipline.

These types of activities provide the following research-based benefits: (Shaw, 3-5)

- They provide concrete examples of abstract concepts, facilitate the development through practice of analytical skills, procedural experience, and decision making skills through application of course concepts in real life situations. This can result in deep learning and the appreciation of differing perspectives.

- They can result in changed perspectives, increased empathy for others, greater insights into challenges faced by others, and increased civic engagement.

- They tend to increase student motivation and interest, as evidenced by increased rates of attendance, completion of assigned readings, and time spent on course work outside of class time.

- Studies show greater/longer retention of learned materials.

- The result is often better teacher/student relations and a more relaxed environment in which the natural exchange of ideas can take place. Students come to see the instructor in a more positive light.

- They often result in better understanding of complexity of situations. They provide a good forum for a large volume of orderly written analysis and discussion.

There are benefits for instructors as well, such as keeping things fresh and interesting in courses they teach repeatedly; providing good feedback on what students are getting and not getting; and helping in standing and promotion in institutions that value teaching and learning.

Outcomes and learning activity alignment

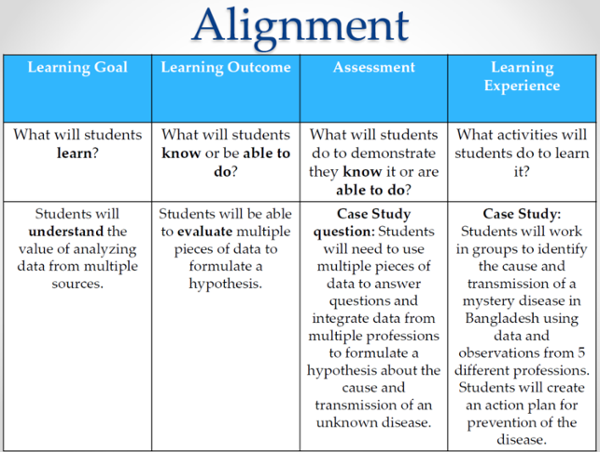

The learning activity should have a clear, specific skills and/or knowledge development purpose that is evident to both instructor and students. Students benefit from knowing the purpose of the exercise, learning outcomes it strives to achieve, and evaluation methods. The example shown in the table below is for a case study, but the focus on demonstration of what students will know and can do, and the alignment with appropriate learning activities to achieve those abilities applies to other learning activities.

(Smith, 18)

What’s the difference?

Scenarios are typically short and used to illustrate or apply one main concept. The point is to reinforce concepts and skills as they are taught by providing opportunity to apply them. Scenarios can also be more elaborate, with decision points and further scenario elaboration (multiple storylines), depending on responses. CETL has experience developing scenarios with multiple decision points and branching storylines with UNB faculty using PowerPoint and online educational software.

Case studies

Case studies are typically used to apply several problem-solving concepts and skills to a detailed situation with lots of supporting documentation and data. A case study is usually more complex and detailed than a scenario. It often involves a real-life, well documented situation and the students’ solutions are compared to what was done in the actual case. It generally includes dialogue, creates identification or empathy with the main characters, depending on the discipline. They are best if the situations are recent, relevant to students, have a problem or dilemma to solve, and involve principles that apply broadly.

Role plays can be short like scenarios or longer and more complex, like case studies, but without a lot of the documentation. The idea is to enable students to experience what it may be like to see a problem or issue from many different perspectives as they assume a role they may not typically take, and see others do the same.

Foundational considerations

Typically, scenarios, case studies and role plays should focus on real problems, appropriate to the discipline and course level.

They can be “well-structured” or “ill-structured”:

- Well-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can be simple or complex or anything in-between, but they have an optimal solution and only relevant information is given, and it is usually labelled or otherwise easily identified.

- Ill-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can also be simple or complex, although they tend to be complex. They have relevant and irrelevant information in them, and part of the student’s job is to decide what is relevant, how it is relevant, and to devise an evidence-based solution to the problem that is appropriate to the context and that can be defended by argumentation that draws upon the student’s knowledge of concepts in the discipline.

Well-structured problems would be used to demonstrate understanding and application. Higher learning levels of analysis, synthesis and evaluation are better demonstrated by ill-structured problems.

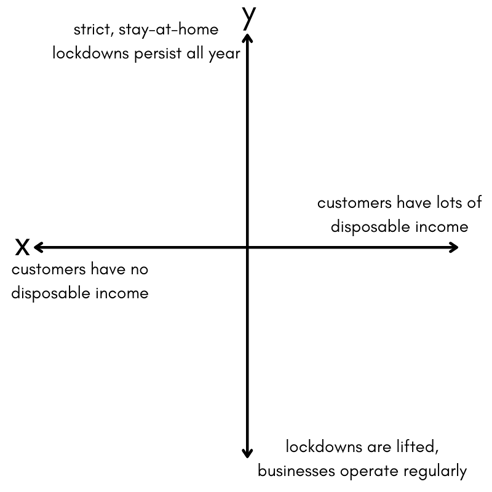

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be authentic or realistic :

- Authentic scenarios are actual events that occurred, usually with personal details altered to maintain anonymity. Since the events actually happened, we know that solutions are grounded in reality, not a fictionalized or idealized or simplified situation. This makes them “low transference” in that, since we are dealing with the real world (although in a low-stakes, training situation, often with much more time to resolve the situation than in real life, and just the one thing to work on at a time), not much after-training adjustment to the real world is necessary.

- By contrast, realistic scenarios are often hypothetical situations that may combine aspects of several real-world events, but are artificial in that they are fictionalized and often contain ideal or simplified elements that exist differently in the real world, and some complications are missing. This often means they are easier to solve than real-life issues, and thus are “high transference” in that some after-training adjustment is necessary to deal with the vagaries and complexities of the real world.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be high or low fidelity :

High vs. low fidelity: Fidelity has to do with how much a scenario, case study or role play is like its corresponding real world situation. Simplified, well-structured scenarios or problems are most appropriate for beginners. These are low-fidelity, lacking a lot of the detail that must be struggled with in actual practice. As students gain experience and deeper knowledge, the level of complexity and correspondence to real-world situations can be increased until they can solve high fidelity, ill-structured problems and scenarios.

Further details for each

Scenarios can be used in a very wide range of learning and assessment activities. Use in class exercises, seminars, as a content presentation method, exam (e.g., tell students the exam will have four case studies and they have to choose two—this encourages deep studying). Scenarios help instructors reflect on what they are trying to achieve, and modify teaching practice.

For detailed working examples of all types, see pages 7 – 25 of the Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS) pdf .

The contents of case studies should: (Norton, 6)

- Connect with students’ prior knowledge and help build on it.

- Be presented in a real world context that could plausibly be something they would do in the discipline as a practitioner (e.g., be “authentic”).

- Provide some structure and direction but not too much, since self-directed learning is the goal. They should contain sufficient detail to make the issues clear, but with enough things left not detailed that students have to make assumptions before proceeding (or explore assumptions to determine which are the best to make). “Be ambiguous enough to force them to provide additional factors that influence their approach” (Norton, 6).

- Should have sufficient cues to encourage students to search for explanations but not so many that a lot of time is spent separating relevant and irrelevant cues. Also, too many storyline changes create unnecessary complexity that makes it unnecessarily difficult to deal with.

- Be interesting and engaging and relevant but focus on the mundane, not the bizarre or exceptional (we want to develop skills that will typically be of use in the discipline, not for exceptional circumstances only). Students will relate to case studies more if the depicted situation connects to personal experiences they’ve had.

- Help students fill in knowledge gaps.

Role plays generally have three types of participants: players, observers, and facilitator(s). They also have three phases, as indicated below:

Briefing phase: This stage provides the warm-up, explanations, and asks participants for input on role play scenario. The role play should be somewhat flexible and customizable to the audience. Good role descriptions are sufficiently detailed to let the average person assume the role but not so detailed that there are so many things to remember that it becomes cumbersome. After role assignments, let participants chat a bit about the scenarios and their roles and ask questions. In assigning roles, consider avoiding having visible minorities playing “bad guy” roles. Ensure everyone is comfortable in their role; encourage students to play it up and even overact their role in order to make the point.

Play phase: The facilitator makes seating arrangements (for players and observers), sets up props, arranges any tech support necessary, and does a short introduction. Players play roles, and the facilitator keeps things running smoothly by interjecting directions, descriptions, comments, and encouraging the participation of all roles until players keep things moving without intervention, then withdraws. The facilitator provides a conclusion if one does not arise naturally from the interaction.

Debriefing phase: Role players talk about their experience to the class, facilitated by the instructor or appointee who draws out the main points. All players should describe how they felt and receive feedback from students and the instructor. If the role play involved heated interaction, the debriefing must reconcile any harsh feelings that may otherwise persist due to the exercise.

Five Cs of role playing (AOM, 3)

Control: Role plays often take on a life of their own that moves them in directions other than those intended. Rehearse in your mind a few possible ways this could happen and prepare possible intervention strategies. Perhaps for the first role play you can play a minor role to give you and “in” to exert some control if needed. Once the class has done a few role plays, getting off track becomes less likely. Be sensitive to the possibility that students from different cultures may respond in unforeseen ways to role plays. Perhaps ask students from diverse backgrounds privately in advance for advice on such matters. Perhaps some of these students can assist you as co-moderators or observers.

Controversy: Explain to students that they need to prepare for situations that may provoke them or upset them, and they need to keep their cool and think. Reiterate the learning goals and explain that using this method is worth using because it draws in students more deeply and helps them to feel, not just think, which makes the learning more memorable and more likely to be accessible later. Set up a “safety code word” that students may use at any time to stop the role play and take a break.

Command of details: Students who are more deeply involved may have many more detailed and persistent questions which will require that you have a lot of additional detail about the situation and characters. They may also question the value of role plays as a teaching method, so be prepared with pithy explanations.

Can you help? Students may be concerned about how their acting will affect their grade, and want assistance in determining how to play their assigned character and need time to get into their role. Tell them they will not be marked on their acting. Say there is no single correct way to play a character. Prepare for slow starts, gaps in the action, and awkward moments. If someone really doesn’t want to take a role, let them participate by other means—as a recorder, moderator, technical support, observer, props…

Considered reflection: Reflection and discussion are the main ways of learning from role plays. Players should reflect on what they felt, perceived, and learned from the session. Review the key events of the role play and consider what people would do differently and why. Include reflections of observers. Facilitate the discussion, but don’t impose your opinions, and play a neutral, background role. Be prepared to start with some of your own feedback if discussion is slow to start.

An engineering role play adaptation

Boundary objects (e.g., storyboards) have been used in engineering and computer science design projects to facilitate collaboration between specialists from different disciplines (Diaz, 6-80). In one instance, role play was used in a collaborative design workshop as a way of making computer scientist or engineering students play project roles they are not accustomed to thinking about, such as project manager, designer, user design specialist, etc. (Diaz 6-81).

References:

Academy of Management. (Undated). Developing a Role playing Case Study as a Teaching Tool.

Diaz, L., Reunanen, M., & Salimi, A. (2009, August). Role Playing and Collaborative Scenario Design Development. Paper presented at the International Conference of Engineering Design, Stanford University, California.

Norton, L. (2004). Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS): A practical introduction to problem-based learning using vignettes for psychology lecturers . Liverpool Hope University College.

Shaw, C. M. (2010). Designing and Using Simulations and Role-Play Exercises in The International Studies Encyclopedia, eISBN: 9781444336597

Smith, A. R. & Evanstone, A. (Undated). Writing Effective Case Studies in the Sciences: Backward Design and Global Learning Outcomes. Institute for Biological Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Campus Maps

- Campus Security

- Careers at UNB

- Services at UNB

- Conference Services

- Online & Continuing Ed

Contact UNB

- © University of New Brunswick

- Accessibility

- Web feedback

5 Scenario Examples to Engage Learners and Build Confidence

by Kathleen Matyas, Senior Strategist

Feb. 8, 2022 / Learning-experience design

Think back to the last time you learned a new skill. How much of your preparation came from simply reading training materials? How much of it came from trying it out for yourself and learning by doing?

Learning is a process , and the application and reflection phases are key to cultivating prepared, confident learners. But it’s not always realistic, or even safe, to teach new skills in the actual environments in which they’re applicable.

That’s where scenario based training comes in. Scenario-based learning is an interactive instructional strategy that uses real-life situations and narratives to actively engage learners. It’s hard to beat the engagement quotient of scenarios, and they’re a proven strategy for boosting learning outcomes. Think about your own approach to scenarios. Are you making the most of scenario-based learning?

We love using scenarios in our learning experiences—they’re a great solution for all kinds of industries and learning objectives. We’ve rounded up some of our favorite scenario based training examples to inspire you to take your learning even further. Let’s take a look at five scenario examples and how they elevated the learning experience.

1. Scenario example for safety and emergency procedures

Need to train team members on how to keep themselves and others safe? Telling them what to do in an emergency or crisis situation usually isn’t enough. People often learn best by doing, but how can you put their safety and emergency procedure skills to the test without putting them or others at risk?

Scenario-based learning is a great way to immerse learners in a realistic yet controlled environment where they can practice skills, play out different situations, and build their confidence. When a crisis occurs in actuality, they’re better prepared to respond without making critical mistakes.

Barton Health safety training

Barton Health needed to train team members on Fire Safety, Medical Equipment Safety, and Radiation Safety. Rather than create a standard compliance course that simply tells the learner how to behave safely, we created an interactive experience where they could identify and manage risks in a simulated healthcare environment.

In this learning experience, users are introduced to a realistic situation at the Barton Health campus: an electrical issue is causing problems in key areas of the hospital. They must make a series of decisions to prevent damage to the building and its equipment by stabilizing two key rooms in the building: the Operating Room and the MRI Room. Each room in the scenario is depicted by illustrations.

In the Operating Room, the learner is prompted to review the fire safety procedures and then identify the items in the room that are fire hazards (while the clock is ticking!). If they identify all items in the room before time runs out, they’ve successfully stabilized the Operating Room and can move on to the MRI Room. If they run out of time, they restart the room and try again. That’s the beauty of a scenario—failing is risk-free and you learn from the consequences.

Before moving on to the MRI Room, the learner is instructed to select the items on their person that need to be removed—all metal objects need to be removed before entering. They then need to select the MRI Technician to gain approval for entry.

Once in, they’re told that the machine is malfunctioning and are challenged with taking the proper steps to safely resolve the situation. If the user completes the required steps in the right order and before the clock runs out, they’ve stabilized the room and won the game. If not, they’re back to the beginning to give it another try.

Like all good scenarios, these scenario examples focus on application. Learning with context often yields much better outcomes, especially when the stakes are high. Setting your scenario in a simulated real-world environment makes it that much more memorable and relatable for learners.

Create enviable courses in Rise

Are you a learning designer who loves trying new things in Articulate Rise? Then you’re going to love Mighty, a powerful little Google Chrome extension built to help you do more in Rise. With Mighty, you’ll get access to exclusive features and functionality that elevate visual design, increase efficiency, and deliver better learner experiences. You can try Mighty for free right now and find out for yourself—start your free trial today!

2. Scenario example for social media conduct training

Global brands almost always have a strong presence across social media platforms, and even something as simple as liking a post on social media can have an enormous effect on the business they do.

Scenarios can help team members feel confident about what they can and can’t post on social media, whether they’re representing the brand or on their personal accounts. You could equip team members with a lengthy social media handbook and trust that they’ll review and retain it on their own—but learning by doing is a better way to translate those practices into real-world situations.

Here’s an example of a scenario for sharing smart social media practices with employees.

Social media best practices training

We partnered with a global hospitality brand to create a social media best practices training that would empower team members to maximize their engagement on social media and avoid unanticipated negative outcomes.

We designed scenario-based training that would inform team members of the brand’s social media best practices and give them an opportunity to practice their knowledge in a low-stakes simulated environment. We created two Articulate Rise modules that explained principles and policies and three Articulate Storyline modules that allowed learners to practice and demonstrate their mastery of the content through challenging and realistic scenarios.

To accomplish this, we replicated the experience of a social media platform. Learners interacted with the modules by liking, commenting on, or sharing posts—the same way they would on social media—and then learned from the immediate consequences of their actions.

Learners began each lesson by adding their name and favorite brand, and these items were featured throughout the training to increase the personalization of the training. As the training progressed, learners navigated complex branching scenarios, with the option to repeat scenarios and choose different responses to understand the downstream impacts of their choices.

3. 3D scenario for lab safety training

Safety is top priority in lab settings—is sharing a handbook with employees enough? Often, safety training is stickier when you give learners the chance to apply safety protocols in a realistic yet safe simulated environment.

Let’s take a closer look at how to use scenario learning to build confidence around lab safety.

Cubist lab safety training

Cubist needed to train employees on how to identify hazards and address them in the appropriate manner. Instead of having learners simply read up on the potential hazards and proper responses, we created an Articulate Storyline course with 3D-rendered cut-scenes that required the learner to apply their knowledge in a simulated lab environment.

Here’s how it works. Learners enter a biology lab and move their cursor over any object or area where they observe a possible safety hazard, selecting anything they believe to be unsafe. If something is in fact unsafe, learners are given several options and choose the best way to correct it. Each option has feedback so they can learn more about each hazard and how to respond. Once they’ve identified and corrected all five hazards, they move on to the chemistry lab to repeat the exercise, with an emphasis on chemical safety.

This is one of our favorite scenario based elearning examples because it requires learners to go beyond acquiring knowledge and apply what they’ve learned. Plus, the 3D renderings in this scenario help to create a true-to-life representation of the lab and actual issues that learners might find themselves facing on the job.

4. Gamified scenario for exploring career paths

If your top priorities are to motivate and engage learners, try incorporating gamification into your scenario. Gamification uses elements like characters, narrative, and rewards to help immerse learners and capture their interest .

Let’s take a look at an example of a scenario that uses gamification to inspire employees to envision their future career paths.

CSL developing people game

CSL is one of the largest and fastest-growing biotechnology businesses and a leading provider of in-licensed vaccines. CSL came to us looking for a thoughtful eLearning solution that would inspire its workforce to imagine their career paths and the many ways in which they can expand their skill sets and grow their careers within CSL.

We decided to take a unique, gamified approach with a choose-your-own-adventure style game that gets users to explore options for their long-term career path at CSL, based on their perceived strengths, skill sets, and goals. Once we determined the paths and events along their journey, we designed characters, events, and player interactions.

Users start by selecting where they are in their CSL journey. From there, they engage in a 10–15 minute experience, making decisions on interactive career pathways that help them travel through their career lifecycle and visualize their future with CSL. The experience served a global, virtual audience of 27,000 employees and required us to conduct a thorough exploration of roles and pathways within CSL.

The outcome? We were able to leverage gamified scenario learning to immerse learners in a positive vision of their futures with CSL and inspire them to start taking steps to make it a reality.

5. Scenario example for explaining complex processes

Product flow is complicated. In order to get it right, learners need to visualize how goods will move from supplier to consumer and all of the small decisions along the way that impact the journey. When it comes to simplifying complex processes, video-based scenario training is a great way to show and not tell and allow learners to think through real-world decisions.

Take a look at one example for using live videos in a scenario.

Product distribution onboarding

As part of onboarding, business analysts and buyers at a regional grocery store chain needed to understand the overall product flow from distribution facility to store. This brand believes in investing in its talent, and they often promote from within. That means people entering these roles are often more junior employees with little experience in distribution facility operations.

It’s a complex undertaking, and it’s critical for new hires to understand how the decisions they make from HQ directly impact the overall product flow. The decisions they make influence which products are available to customers in-store, which ultimately impacts the customer’s overall experience. Those are high stakes, and we knew it would take an immersive and engaging learning experience to help train the company’s BAs and buyers for success.

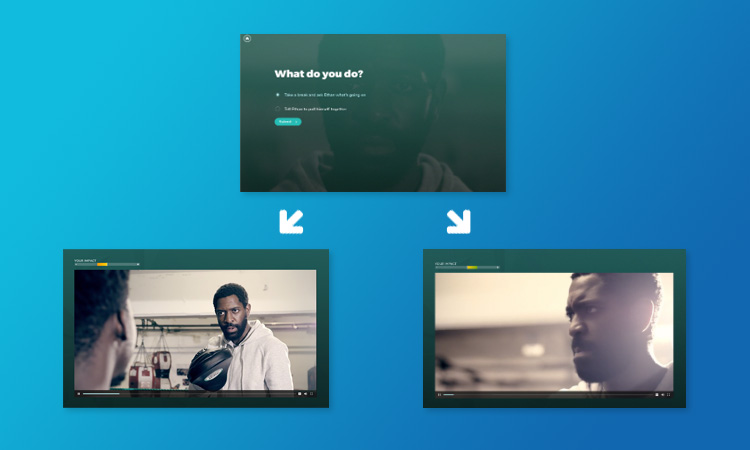

For this training, we created live-action videos to depict three unique scenarios. Our goal was to show learners how a product moves from distribution to stores and provide examples of critical decisions they’ll face to make the process run more smoothly. We made sure the videos seamlessly represented the store, the distribution facility, and HQ in order to visually show how each one impacts the other.

Nobody likes watching boring videos, so we took a fun and cheeky approach to these scenarios. We used actual company employees as actors (plus some Maestro team members!) to set up three situations, then prompting the learner to choose the best approach to resolve the problem. After the learner makes a decision, a summary video shows the outcome of all three presented options, highlighting which approach is best and why.

Especially when a learner is new to a role, it’s challenging to see the full scope of your decisions and influence. These video-based learning scenarios helped learners to transcend their environment and think beyond the walls of HQ. The training helped them see the big picture and explore why seemingly viable approaches might not be the best choice after all.

Scenarios prepare learners for success

For learning to be effective and really change the way we think and act, it needs to account for the way our brains process and absorb new information. These scenario examples serve as inspiration to show what’s possible in eLearning. Scenario-based learning is powerful: learners can practice their skills, learn from the consequences, and repeat the exercise until they get it right.

There are more scenario examples where that came from.

Our gamified approach to bartender training for Royal Caribbean earned a Brandon Hall Gold Award.

Training the next generation of crypto traders

We’re developing a first-of-its-kind learning experience that gives OKX’s new traders the confidence to succeed.

Our experiential, consumer-grade crypto learning academy is designed to deliver a comprehensive introduction to crypto trading for OKX’s 20 million users.

VetBloom A blockchain-based credentialing platform for veterinary specialties

Acist medical systems lifelike 3d product training to guide service techs on the job, best western hotels & resorts helping transform brand culture with fresh, energizing ilt.

- The Simplest Way to Avoid the Research Fail of the Yellow Walkman

- 5 Sets of Tried-and-True Resources for Instructional Designers

- Are You Skipping the Validation Step? Why Piloting Your Learning Matters

Ohio State navigation bar

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

How to Build an Effective Scenario-Based Learning Activity

Article written by ASC Office of Distance Education Instructional Designer, Jessica Henderson.

This article expands upon the ASC ODE article, “ Scenario Based Learning’s Potential for Online, Asynchronous Learning and Beyond ”, which explores the evidence behind the effectiveness of Scenario Based Learning (SBL) in building higher-order thinking skills and the ways in which such a strategy can support student learning and engagement, particularly in online, asynchronous environments. The article here will dive into the actual design stage involved in crafting an SBL activity, as well as considerations for which supported tools are best suited for delivering SBL activities online.

As an introduction to this resource, and in an effort to provide a succinct summary of the article linked above, Scenario Based Learning (SBL) is an active learning strategy that guides learners through simulated events via the incorporation of narratives and authentic, or real-world, contexts. SBL:

- has proven effective in building higher-order proficiencies, and other highly sought-after transferable skills,

- necessitates intensive effort dedicated to planning, testing, and implementation from instructors to effectively execute, and

- requires additional considerations such as which supported tool will best serve the activity needs and meet the learning objectives, what additional instructions will need to be provided to learners to ensure clarity, and where and how will the activity be delivered.

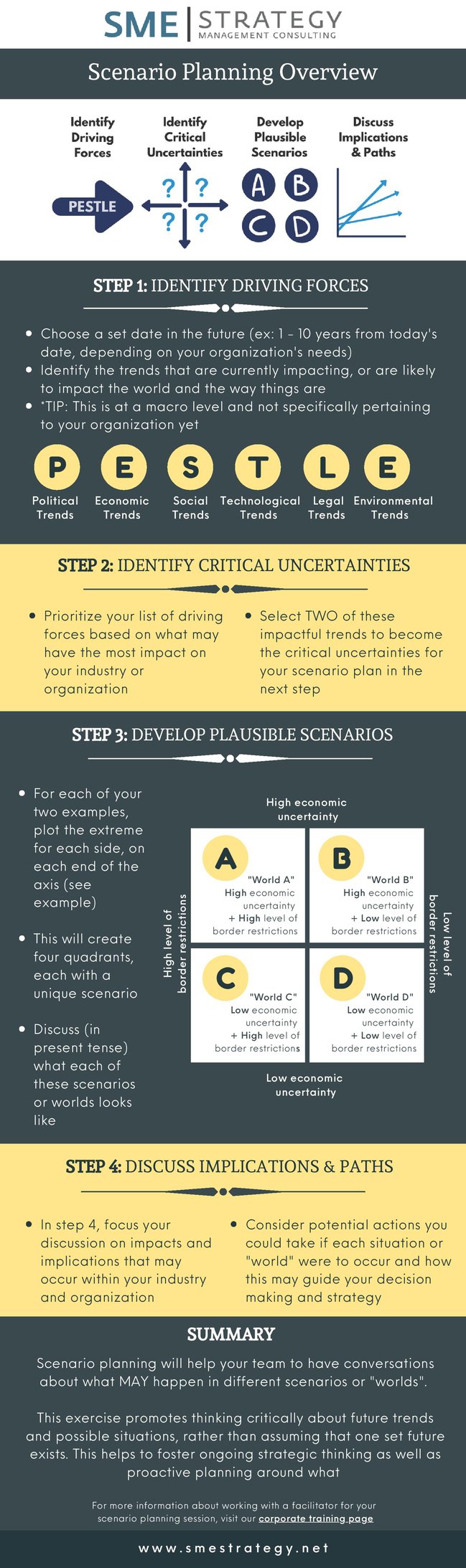

SBL Development Frameworks: ADDIE and EMERGO Methodology

Developing an SBL activity is not unlike designing a new course. The same sorts of backwards design strategies used in planning academic courses can ensure that the design of the scenario-based activity will be both efficient and student-focused, leading to the achievement of desired learning outcomes.

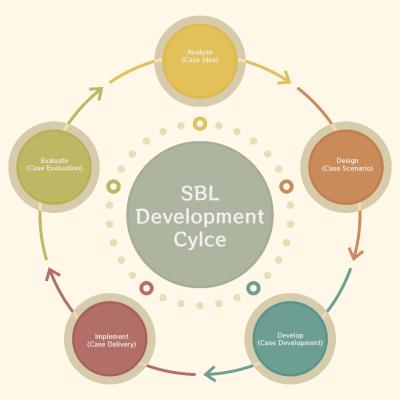

One specific backwards-design style framework that has been used to guide the development of SBL activities is referred to as the EMERGO methodology [1] EMERGO is founded on the principles of a well-proven instructional design model known as ADDIE [2] , an acronym that stands for Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate.

EMERGO takes the ADDIE cycle and extends it to simulated tasks and environments. Each phase of the EMERGO methodology is described below, with the greatest attention being given to the Design and Develop stages, as these tend to be the most challenging of the cyclical steps.

Step 1: Analyze

The development of any SBL activity should begin by analyzing the why: Why is this activity needed? Why is SBL well-suited to this task or assignment? In short, this initial step equates to the articulation of the broader goals and subsequent learning outcomes desired as a result of the particular exercise.

As you contemplate and begin to draft your goals and outcomes for the activity, here are a few questions that may help you get started:

- What technical skills do you want students to gain by completing the activity?

- What transferable skills, higher-order cognitive thinking, do you want students to practice and develop?

- What principles of quality online teaching and learning and Universal Design for Learning are most important to you to consider and apply within this activity and what challenges or limitations might arise regarding their implementation? (e.g. community building, student engagement, motivation, metacognitive practices, instructor presence, transparency in design, multiple means of representation, etc.)

- How will the achievement of goals and outcomes be assessed?

- What prior knowledge might students need to complete the task?

- Will the activity serve as a stand-alone task or as an introductory exercise to a large assignment?

- How does the activity figure into the overall student workload estimation?

Be sure to document and save your responses to these and other pertinent questions, along with the goals and outcomes that they help to shape. You will use these responses and established outcomes as a guide throughout each of the following stages.

For more about the types of situations that may be well-suited to SBL activities, be sure to explore this specific section in the ASC ODE Scenario Based Learning’s Potential for Online, Asynchronous Learning and Beyond article.

Step 2: Design - The 5 Cs of Scenario-Based Learning

Once you have completed the analysis stage and established your goals and outcomes, it is time to start designing the activity by mapping out the framework and inner workings of the scenario. But where do you even begin?

The EMERGO methodology chunks the Design stage into three scaffolded steps that can help to streamline the activity creation process. These three steps include laying out the following: 1) the Framework Scenario, 2) the Ingredients Scenario, and 3) the Detailed Scenario.

The Framework Scenario

The Framework scenario functions as a general outline or template that helps to structure the final detailed activity. The framework will generally consist of one or more blocks containing five core types of elements, helpfully referred to as the 5Cs of Scenario Based Learning 3 . The 5Cs are:

- Context : This includes any background information, such as place, situation, time period, etc. that help to establish and frame the challenges and choices that students will face.

- Challenge : Challenges are the specific problems and questions that will test students’ technical understanding and/or ability to think critically.

- Choices : The choices are the possible pathways and solutions that students will encounter in response to the challenge.

- Consequence : Each choice is followed by a consequence. Consequences can be positive or negative, and of varying degrees. These are the points in the scenario where feedback happens, allowing students to check their understanding and progress, and reflect on the outcome of a specific decision.

- Contemplate : Contemplate may refer to several smaller direct moments invoking reflection through direct instructor feedback or reflection prompts. This element could also appear in the form of a larger reflection question related to the experience of the activity as a whole.

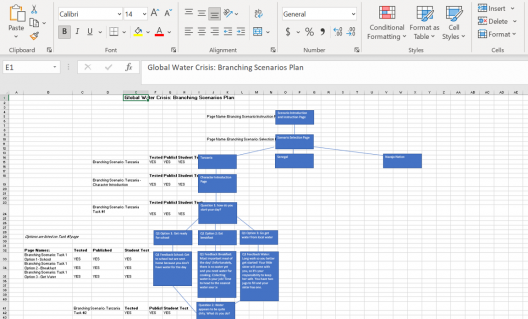

As part of this step, it is helpful to map out each of these elements in a basic outline or visual flowchart, either via pen and paper or by using an online tool like Microsoft Word, Excel or Visio:

As you begin to organize your activity:

- Think first about the challenges that you want students to encounter, those concepts that speak directly to the learning outcomes and that will provide evidence that students have met those outcomes. List out those challenges to determine how many you will need to include and in what order they might appear.

- Next, consider what background knowledge and context might help to frame the challenges that students will face. What information might students need to help them think critically about the events at hand? Then, work your way through the choices. What are some possible, realistic pathways that may stem from the challenge in question? Try to keep the number of options limited to three or four so as not to overwhelm and complicate the actual development process and overall size of the scenario.

- Finally, consider, at a global level, what feedback and reflection questions will be associated with each decision. Will the feedback be positive? Negative? Will students earn higher points for choosing one path over another? Where might you incorporate prompts for deeper reflection?

The Ingredients Scenario

After you have outlined the framework scenario, it is time to begin adding some surface-level details to each element. Here, you will consider things such as what specific tasks students might complete, (e.g. completing a puzzle, interacting with a virtual tour, conducting Internet research, etc.) what tools and resources might you consider using to complete the tasks, in what format information might be presented, and the amount of flexibility students have (i.e. can students navigate backwards within the scenario you design to quickly try again or do they need to work their way through an entire path before making a second attempt? Do they need to get an answer correct before they can proceed to the next challenge? Etc.).

The Detailed Scenario

The last step of the design stage is to fill in the gaps. This is where you will identify, collect, and/or create the content that will be used to develop the scenario. This includes writing out scripts for any videos that might need to be created, collecting a list of resource links that will need to be shared, locating and saving visual elements, etc. It is also at this point that you will identify and select the specific tools that will be used for each element. For example, if you are incorporating your own videos, what will you use to record, store, and share those video files? If you need to incorporate fill-in-the blank or multiple choice questions, what quizzing tool or features will you use?

Step 3: Develop - Choosing the Right Platform for Delivery

Following the design stage comes the development stage. This is the point where you bring all of the individual pieces together into a working draft of an interactive activity and run the activity through multiple rounds of testing to ensure functionality and accuracy.

When it comes to developing a digital branching scenario activity, there are currently three primary tools supported either by the university or the College of Arts and Sciences that we recommend for the creation fo SBL activities. Each one of these tools contains positives and negatives that must be weighed against one another to determine the best platform for your specific activity. The advantages and disadvantages of each are outlined below.

SBL activities can be designed directly in Carmen by creating individual Pages and strategically linking them together to form various pathways.

- Consistency: Instructors and students of online Ohio State courses are likely already familiar with Carmen and its general functionality.

- No need to learn additional tools: No external tools are required, which means there is little to no learning curve when it comes to the technology used.

- Independence: Instructors can create and manage basic pages and link them without having to rely extensively on external support.

- Difficult to grade and associate with points: Because the activity relies on several Pages that are linked together, it is difficult, if not impossible, to associate these activities with points and the gradebook without complex workarounds and less-transparent navigation, which could result in a high level of confusion.

- Understanding student use is a challenge: For similar reasons to the point above, gathering statistics on how and which students are working through these activities is very limited and difficult to gather, which may make it more challenging to evaluate the effectiveness of the activity in an online environment.

- Limited to multiple choice or true/false: Relying on linked pages, generally means that any questions incorporated in the activity must be either multiple choice or true/false.

- Clunky and not well-suited for larger scenarios: Building SBL activities in Carmen requires a great deal of organization. The developer must keep track of each and every page name and where that page links. This organization must be done outside of Carmen, as Carmen itself does not contain the types of visual flowchart layouts that other SBL tools include. Furthermore, making updates to page name after they have already been linked elsewhere can create difficulties. When page names change, any corresponding links will break if the name change is not reflected in all linked locations.

- Lacking in User Experience: Unless you are familiar with some HTML code, basic pages in Carmen do not offer the best User Experience.

- Potential for decreased motivation : The lack of visual variety can negatively impact student engagement and motivation.

For more details and a video tutorial that demonstrates how to build branching scenarios using Carmen Pages refer to the ASC ODE article Enhance Your Course Design and Increase Student Engagement with Creative Carmen Pages

- Integrated with Carmen and the gradebook: By incorporating Goal Point blocks, students receive points when they make certain decisions or achieve certain goals. If the activity is set up as a Carmen assignment using the ThinLink integration, points will automatically transfer to the Carmen gradebook.

- User-friendly platform: Both from the developer’s side and the participant’s side, the ThingLink platform is very intuitive and easy to use and does not require a large learning curve.

- Visual organization: The interface incorporates a visual flowchart and color coding to make it easier to visualize and keep track of each block and connection within the scenario.

- Flexibility related to content: You can embed or link to just about anything in ThingLink, including external images, videos, and audio files, other ThingLink scenes and virtual tours, etc.

- Timers: Of the three tools discussed, ThingLink is currently the only one that allows you to add timers, either to the entire scenario, or to individual blocks. This can be particularly helpful for lower-stakes exercises where you want to provide added challenges.

- Detailed statistics: Within the ThingLink Scenario Builder you can turn on advanced tracking to view details about how your students are interacting with the activity, either as a whole or by individual user. You can see things such as each path a student took, the most common paths taken, and average time spent on an individual block.

- Independence on the part of the instructor: Instructors within the College of Arts and Sciences can manage and design scenarios on their own. But they also have the option to add collaborators for additional support or collaboration across courses.

- Some limitations to question types: You can incorporate true/false, multiple choice, and open-ended questions directly in ThingLink. However, open-ended questions must be answered correctly before a student can proceed.

- Limits to customization of settings: Some general settings, such as the text of the Proceed button, are not fully customizable.

- Points are taken as a percentage: ThingLink calculates the final points a student earns as a percentage of the total points included in the scenario. If you are building a scenario where students don’t necessarily need to complete every pathway or you want to have different pathways be worth a different number of points (e.g. one pathway may be more correct than another), this may lead to an inaccurate or misleading final score, as it will overwrite the point total added to the Carmen assignment and reflect the total points contained within the scenario itself.

- Integrated with Carmen and the gradebook: Points can either be calculated by assigning a total to the end of a complete pathway or they can be calculated dynamically by incorporating quiz questions throughout. These points transfer automatically to the Carmen gradebook as a total point value.

- Flexibility in terms of question types: H5P allows for the most flexibility in terms of questions. Multiple-choice, Select All, True/False, and Fill-in-the blank can all be incorporated in H5P without the requirement that students answer correctly before proceeding to the next task.

- Visual variety: Content can be displayed in a variety of layouts, combining multiple forms of media in a visually clean and engaging way.

- Customizable settings: H5P provides a good deal of customization when it comes to general settings, such as the text that appears on the beginning and end screens or on navigation buttons.

- Detailed statistics: H5P contains detailed reports for branching scenario activities that have been added via the Carmen integration. Through these reports you can see information by student such as the number of attempts made, the time of both the first and last attempt, the first, last, best, and max scores, the total time spent on the activity, and the individual answers selected for each question or branch.

- Some limitations in terms of content: The types of content that can be embedded in H5P are a bit more restricted. You can incorporate videos, audio, images, and text. You can also link to a variety of content, but you generally cannot embed external content in an H5P scenario unless you have the actual media file on hand and can upload it to the platform.

- Some limitations to scoring : While the variety of questions and overall score transfer to Carmen function rather well, points are limited to either being set at the very end of the scenario or by incorporating quiz questions. It is more difficult to award points after individual branching actions and requires some workarounds.

- Higher dependency on external supports: Content created in H5P (following standard operating procedures and agreements with the ADA Coordinator’s Office to ensure security and accessibility for students), must be created and managed by ASC ODE Instructional Designers. Thus, instructors must depend more heavily on collaborative efforts with external partners to develop and manage SBL activities using H5P. This also means that any data reports associated with the content are collected and managed by the Instructional Designers. If an instructor wishes to view the statistics, they must first reach out to the ASC ODE Instructional Designer to request access to the specific data report.

Additional details and content examples utilizing H5P can be found in the ASC Resource article H5P: A Tool for Creating Interactive Course Content .

Steps 4 & 5: Implement and Evaluate

The final steps in developing an effective SBL activity are to implement the activity in the classroom and evaluate whether or not the activity achieved the goals and learning outcomes set forth in the analysis stage, identifying areas for adjustment and improvement going forward. It is also beneficial to gather qualitative feedback from the learners themselves to gain a holistic view of their experience in terms of engagement, functionality, ease of use, and even their own self-assessment and perception of their personal skill development.

Additional Resources and Support

For additional information about Scenario-Based Learning and helpful frameworks, we encourage you to explore the following resources. If you would like additional support in developing an SBL activity, our Instructional Designers are here to help brainstorm, collaborate, and offer additional support. Request a consultation today!

- Scenario Based Learning’s Potential for Online, Asynchronous Learning and Beyond

- ThingLink: Creating Scenario Based Learning Experiences

- Enhance Your Course Design and Increase Student Engagement with Creative Carmen Pages

- ThingLink: An Interactive Tool for Instructors and Students

- H5P: A Tool for Creating Interactive Course Content

[1] Nadolski, R. J., Hummel, H. G., van den Brink, H. J., Hoefakker, R. E., Slootmaker, A., Kurvers, J. H., & Storm, J. (2008, September). EMERGO: A methodology and toolkit for developing serious games in higher education. SIMULATION & GAMING, 39 (3), 338-352.

[2] University of Washington | Bothell. (2023). Information Technology . Retrieved from ADDIE https://go.osu.edu/ChWU .

[3] ThingLink. (n.d.). Creating Scenario Based Learning Experiences. Retrieved from thinglink.com: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qxPrdw2LnIU-Xj59CIKvfs1onKFikOA5/view?pli=1

- AI Community

- L&D On-Demand

Scenario-Based Learning: 7 Engaging Examples for Formal and Informal Education

Thomas Bril

Imagine a classroom where learning is not confined to textbooks and lectures, but extends into real-life situations. Scenario-based learning offers a revolutionary approach to education, providing students with immersive experiences that foster critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In this article, we will explore the concept, mechanics, and benefits of scenario-based learning , both in formal and informal education settings. Brace yourself for a journey into an exciting realm where education meets reality!

Understanding Scenario-Based Learning

At its core, scenario-based learning involves presenting learners with real or fictional scenarios, in which they must apply their knowledge and skills to make informed decisions. This pedagogical approach goes beyond rote memorization, encouraging active engagement and critical analysis.

Scenario-based learning is a dynamic and interactive method that allows learners to actively participate in their own learning process. By immersing students in realistic scenarios, educators can create a stimulating and engaging environment that promotes deep learning and critical thinking .

One of the key concepts in scenario-based learning is the idea of authenticity. By placing learners in authentic contexts, scenario-based learning allows them to witness the consequences of their choices firsthand. This experiential learning approach enables students to develop a deeper understanding of complex concepts and gain practical experience that they can apply in real-world situations.

The Concept and Importance of Scenario-Based Learning

Scenario-based learning places learners in authentic contexts, allowing them to witness the consequences of their choices firsthand. By simulating real-world scenarios , students gain practical experience and develop a deeper understanding of complex concepts. The importance of this approach lies in its ability to bridge the gap between theory and practice, preparing learners for the challenges they will face in their professional lives.

Imagine a scenario where medical students are presented with a simulated emergency situation in a hospital setting. They are required to make critical decisions under pressure, just as they would in a real-life emergency. By engaging in this scenario, students not only apply their theoretical knowledge but also develop essential skills such as teamwork , communication, and problem-solving.

Furthermore, scenario-based learning promotes active engagement and critical analysis. Instead of passively receiving information, learners are actively involved in the learning process. They must analyze the scenario, evaluate different options, and make informed decisions based on their understanding of the subject matter. This active engagement enhances their ability to think critically and apply their knowledge in practical situations.

The Role of Scenario-Based Learning in Education

Scenario-based learning has the power to revolutionize education by creating meaningful learning experiences. It promotes active learning , collaboration, and problem solving. By immersing students in realistic scenarios, educators can facilitate deep learning, enabling learners to connect theory to real-world application.

The #1 place for Learning Leaders to learn from each other.

Get the data & knowledge you need to succeed in the era of AI. We're an invite-only community for L&D leaders to learn from each other through expert-led roundtables, our active forum, and data-driven resources.

Collaboration is an essential aspect of scenario-based learning . In many scenarios, students are required to work together in teams, simulating real-world collaborative environments. This not only enhances their teamwork skills but also exposes them to diverse perspectives and encourages them to consider different viewpoints.

Moreover, scenario-based learning fosters problem-solving skills. When faced with a scenario, learners are challenged to identify problems, analyze information, and develop effective solutions. This process of problem-solving strengthens their ability to think critically and creatively, preparing them for the complex challenges they may encounter in their future careers.

Overall, scenario-based learning is a powerful educational tool that promotes active learning, critical thinking, and practical application of knowledge. By incorporating this approach into their teaching practices, educators can create transformative learning experiences that prepare students for success in the real world.

The Mechanics of Scenario-Based Learning

Central to the success of scenario-based learning is the careful design and implementation of effective scenarios. Let’s delve into the key components of this process:

Designing Effective Scenarios for Learning

Creating scenarios that captivate learners requires careful thought and planning. Engaging scenarios should be relevant, challenging, and aligned with learning objectives. By considering the learners’ prior knowledge and experiences, educators can tailor scenarios to their needs, ensuring maximum engagement and knowledge retention .

Implementing Scenario-Based Learning in the Classroom

While designing scenarios is crucial, their effective implementation is equally important. Scenario-based learning can be integrated into classroom activities through role-playing exercises, case studies, or even simulations. Engaging students in active discussions and reflections further enhances their learning experience .

Scenario-Based Learning in Formal Education

In formal education settings, scenario-based learning offers numerous benefits that go beyond traditional teaching methods. Let’s explore some of these advantages:

Benefits of Scenario-Based Learning in Formal Settings

Scenario-based learning enhances student engagement, as it transforms passive recipients of knowledge into active participants in the learning process . By immersing students in realistic scenarios, educators empower them to apply their knowledge, develop critical thinking skills, and collaborate effectively with their peers.

Challenges and Solutions in Applying Scenario-Based Learning in Formal Education

Implementing scenario-based learning in formal education can present challenges, such as time constraints or resistance to change. However, these obstacles can be overcome through proper planning, support from stakeholders, and providing resources and training to educators. By embracing scenario-based learning , formal education can evolve into a dynamic and student-centered environment.

Scenario-Based Learning in Informal Education

Informal education settings, such as workshops or community programs, can greatly benefit from scenario-based learning . Let’s uncover the advantages it offers:

Advantages of Scenario-Based Learning in Informal Settings

Informal education is characterized by its hands-on nature and focus on practical skills. Scenario-based learning aligns perfectly with these principles by offering learners the opportunity to apply their knowledge in real-life situations. By engaging in scenarios, learners can experience the consequences of their actions firsthand, fostering deeper learning and enhancing their problem-solving abilities.

Overcoming Obstacles in Implementing Scenario-Based Learning in Informal Education

While informal education environments may seem conducive to scenario-based learning , challenges can still arise. Limited resources, lack of expertise, or resistance to change can hinder its implementation. However, by fostering collaboration among educators, leveraging technology, and providing ongoing support, these obstacles can be successfully overcome.

Measuring the Impact of Scenario-Based Learning

Evaluating the effectiveness of scenario-based learning is essential to identify areas of improvement and measure the impact on students’ learning outcomes. Here, we explore ways to assess the impact of this innovative approach:

Evaluating Learning Outcomes from Scenario-Based Learning

Assessing the learning outcomes of scenario-based learning can be done through a variety of methods, such as performance assessments, self-reflections, or peer evaluations. These evaluations provide valuable insights into students’ abilities to apply knowledge, think critically, and collaborate effectively.

Future Prospects of Scenario-Based Learning in Education

As the educational landscape continues to evolve, scenario-based learning is poised to play a significant role. With advancements in technology and growing recognition of the importance of practical skills, scenario-based learning offers a promising future for education. By providing learners with engaging and immersive experiences, it equips them with the skills necessary to thrive in a dynamic world.

In conclusion, scenario-based learning offers a transformative approach to education, bridging the gap between theory and practice. By immersing students in realistic scenarios, educators help them develop critical thinking , problem-solving skills, and real-world readiness. To unlock the full potential of scenario-based learning, organizations like Learnexus are committed to providing educators with the tools and resources needed to implement this innovative approach effectively. Join the scenario-based learning revolution today!

Find the best expert for your next Project!

Related blog posts.

What to Know About Augmented Reality for eLearning

Augmented reality (AR) is transforming the landscape of eLearning, offering unique and interactive ways to engage with educational content. ...

Digital Ignite Consultants on Learnexus

Discover how Digital Ignite Consultants can help you ignite your digital presence and drive success on Learnexus....

Trakstar Performance Management Consultants on Learnexus

Discover the power of Trakstar Performance Management Consultants on Learnexus....

Join the #1 place for Learning Leaders to learn from each other. Get the data & knowledge you need to succeed in the era of AI.

Join as a client or expert.

We’ll help you get started

Hire an Expert I’m a client, hiring for a project

Find a job i’m a training expert, looking for work, get your free content.

Enter your info below and join us in making learning the ultimate priority 🚀

Join as an employer or L&D expert

I'm an employer, hiring for a project

I'm an L&D expert, looking for work

Already have an account? Login

- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

13 Scenario-based Training & Learning Examples

Training design – Cathy Moore

12 scenario-based training examples

Branching scenarios help people practice doing what they do on the job and learn from the consequences. Here are several examples from scenario-based training to give you ideas..

The inclusion of an activity on this page doesn't mean, "Hey, you should do exactly this!" I chose these examples because they raise questions that will help you think more deeply about your own scenario design.

1: Steer the client in the right direction

By Cathy Moore , developed in Twine Carla wants you to create a course about a personality inventory. She says the course will help managers be more empathetic. She's already created a slide deck, so it should be easy!

This project will be another time-wasting information dump unless you steer Carla in a better direction. Try the scenario .

Chapter 3 of my book describes how to start projects right by encouraging clients to analyze the performance problem, not just throw training at it. This scenario helps you practice a small part of that skill.

Questions to consider: This scenario isn't meant to stand alone. It's a small part of the Partner from the Start toolkit. It's preceded and followed by many more activities, all designed to help you practice starting a project right with a client like Carla.

However, it's common for designers to create just one activity for each skill. For example, they present some tips and then have learners practice with one scenario.

How effective would this activity be if it were the only practice you had for managing the handoff conversation? If you used just this scenario, would you be able to manage your next handoff meeting with significantly better results?

2: Connect with Haji Kamal

By Kinection with Cathy Moore, developed in Flash You’re a US Army sergeant in Afghanistan. Can you help a young lieutenant make a good impression on a Pashtun leader? That’s the challenge behind “Connect with Haji Kamal.” See a video of the activity and learn how it was designed .

This activity is a small part of larger training. It was designed to stimulate discussion in a live session. Soldiers completed the activity the night before a classroom session.

Questions to consider: What kind of feedback does the activity provide? Why didn't we just tell players what they were doing right or wrong? Why did we include two helpers who don't agree?

3: Hana Feels

By Gavin Inglis , developed in Twine Something is bothering young Hana. Can you figure out what it is and find the best way to help her? You choose what several people say, including a crisis line volunteer, Hana's boss, and a friend. Play it here .

Questions to consider: You don't choose everything that each person says. Instead, you pick a statement that might send the conversation down a different path, and the author fills in the rest of the conversation. How could you apply this to soft skills training, such as an activity on handling a difficult conversation? Or is it better to require the player to choose every statement their character says?

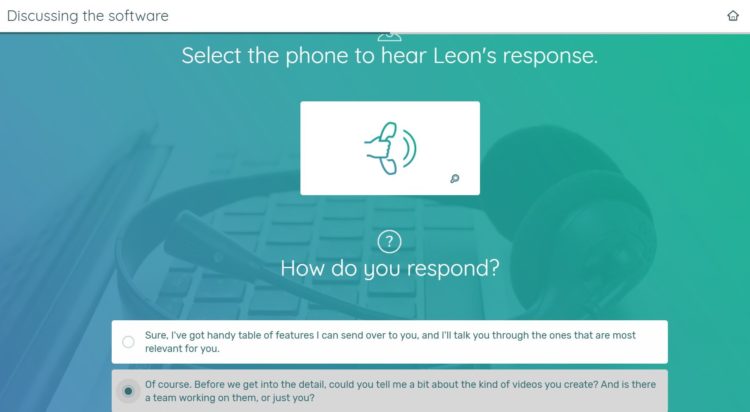

4: Sales simulation with audio

By Elucidat You sell video editing software, and you know that Leon might need your software. Is he really a good prospect? Try the activity .

Questions to consider: The activity encourages you to review some basic information before the call, but it's not required. What does this tell you about how the designers view your intelligence? Does that affect your motivation?

You're given only two choices at each point. Does that feel like enough? Would the activity be more challenging with more options, or would the additional choices feel like a burden?

At each decision point, you get instant corrective feedback. How does that affect the "feel" of the simulation? Does it matter?

For the audio, the developers used an actor who sounded natural. Often, voice actors sound like they're reading a script. What made the actor sound more natural? How could you coach a voice actor to sound this way?

5: Costas is HIV positive

Developed as part of the WAVES Network You've discovered that your patient, Costas, is HIV positive. He doesn't want to tell his wife. What can you do? Try the scenario .

Questions to consider: The scenario has an "old school" look. Many designers invest a lot of effort into making their activities look more slick. How important is a slick look? For example, did you need to see a photo of Costas in order to make your decisions? Did the look and feel of the activity affect your ability to be pulled into the story?

In my scenario design toolkit , I have participants go through a similarly "old school" scenario. Participants often say that they didn't need to see photos of the characters or other bells and whistles -- the story was compelling enough on its own. However, clients and learners may expect a higher level of production.

Your goal is apparently to get the best result for both Costas and his family. How difficult is it to reach that result? Did you want help or hints to make it easier?

6: Medical diagnosis scenario

By SmartBuilder , developed in SmartBuilder Your patient has bruising and swelling on her face. What questions should you ask her to quickly make the right diagnosis? Try the scenario, which is "Patient Management" on this page .

Questions to consider: Compared to the previous medical scenario, this one is more "slick." How does the production style affect your learning? What are some arguments for investing in this level of production?

You'll diagnose the patient by asking questions. The scenario requires you to choose all your questions at once, before you can read the answer to any of them. The patient's answer to one question sometimes makes a question you chose earlier irrelevant.

Why might the designers have chosen this approach? Why don't they let you choose one question at a time and let the patient's response help determine the next question, as happens in the real-world exam? (My guess: Their approach requires less branching, but it means that the scenario isn't as realistic.)

7: Sexual harassment training scenario

By Will Interactive You're a manager and need to respond to several situations that might affect the professionalism of the workplace. How should you respond? Try the demo .

Questions to consider: Why did the designers use video rather than text or text with images? What do they gain from video, and what potential problems does the format create?

Why did the designers give you only two options at most decision points? What would be the effect on your decision-making if you had three options instead? What type of feedback did you usually receive? Was it a natural consequence of your choice? Did this affect your motivation in any way?

8: Learn to speak Zeko

By Cathy Moore ; developed in Twine You’re a journalist rushing to a hot story in Zekonia, but your guide doesn't speak English. Can you learn enough Zeko to follow his directions? Try the scenario

This experimental scenario shows one type of scaffolding: It structures the activity so people learn a bit at a time, building on previous knowledge. In contrast, the traditional approach would be to first present the basic Zeko words and have you memorize them, maybe as a flashcard game that translates from English to Zeko and back again. Only then would you be allowed into a story to "apply what you've learned."

Instead, I throw you directly into the activity. The activity itself teaches you the words, in context, one at a time. This avoids inefficient, in-the-head translation and gives your brain a stickier way to store the information, as visuals or scenes in a story. At least, that's the idea.

9: Set up the laptop technical training scenario

By SmartBuilder , developed in SmartBuilder You need to help someone set up their laptop for a presentation that starts in a few minutes. Try the original Flash version of the activity , and compare it to the newer version under "Using Computer Ports" on their examples page .

Questions to consider: Why does the designer let you skip the "learn about the ports" section? In the new version of the activity, you have to drag the cable to the correct port. Is this better than just clicking on it? Finally, the new version uses photos that show stronger emotion. What is the effect of this?

10: Residential technician training

By Allen Interactions Can you find the problems with this equipment and choose the correct replacement? Plumbing, electrical, and HVAC technicians practice realistic tests and make decisions in this activity .

Questions to consider: The challenges are preceded by cheerful text explanations. Are the explanations helpful? Could they be made more concise, or should they be left as they are?

Instead of seeing the consequence of our decision, we're given corrective feedback, such as being told we chose the wrong motor. Why did the designers take this approach?

We don't know if the learners were also given references to use in the field. Do you think people will remember what they learned in the interaction, or should they have some job aids to take with them? What information in the activity could be turned into a job aid?

The description of the project doesn't include the business goal. What problems might this type of elearning help solve? How might we measure the success of this project?

11: Weak example of a branching scenario

By Cathy Moore , developed in Mac Keynote and Hype Your client wants you to convert her content into an online course. Can you steer her away from that bad idea? Try this simplistic scenario that I created several years ago to test some ideas.

This is a weak scenario. Many scenarios I see are like this one -- the decisions are too easy and the stock photos unnecessary. The idea is solid, but because I spent so long sourcing graphics and building slides, I had little time to write a decent challenge. My slide-based tool (similar to PowerPoint) made extensive branching difficult, so I made the story too simple. For a more realistic scenario on the same topic, see the first example on this page.

12: Example of a "branching" scenario that doesn't branch

I like to call this structure the "control freak" scenario. It works like this: You're presented with the first scene of a story and choose an option, let's say B. You see immediate feedback that tells you that you chose incorrectly, and that you should really do what's described in option A. The scenario sends you back to the same scene and this time you obediently choose A.

Now you see the second scene, and the process repeats. If you choose correctly, the story advances. If you choose incorrectly, you have to go back and do it right. There's usually plenty of feedback telling you what you did wrong and what you should do instead.

A lot of designers create this structure as their first scenario. It's easier to manage than full branching, and all the teacherly feedback feels familiar and "helpful." But do adults really learn best when they're constantly interrupted and corrected? How might the structure and feedback affect people's motivation?

Scenario design toolkit

Learn to design scenarios by designing scenarios, on the job. This self-paced toolkit walks you through all the steps, and interactive tools help you make the tricky decisions.

Build your performance consulting skills

Stop being an order taker and help your clients solve the real problem. The Partner from the Start toolkit helps you change how you talk to stakeholders, find the real causes of the problem, and determine what type of training (if any!) will help.

5 inspiring scenario-based elearning examples

8 minute read

Senior Design Consultant

Scenarios can be an effective way to engage your learners and really change their behavior. Here are five scenario-based elearning examples to inspire your next project.

What is scenario-based learning?

Scenario-based training is a form of training which focuses on learning by doing. It uses real-life situations to support active learning . Rather than passively absorbing information, learners are immersed in a story. Using realistic work situations provides relatable, relevant, and impactful learning experiences. Adding interactivity to the scenario enables users to make decisions and learn through experiencing the consequences of their choices.

From compliance to soft skills, scenario-based learning can be applied to meet most corporate training needs. It can be your main learning strategy or part of a flexible blended learning journey. The approach can be used in online training for the workplace, as well as to enrich face-to-face training and Virtual Instructor Led Training (VILT). Scenarios can be set up using simple text with images, more immersive videos or even Virtual Reality (VR).

Why use scenario-based training?

Scenario-based learning is a popular strategy for online training. It offers lots of advantages for colleagues and companies.

Here are our top benefits of scenario-based training:

- Context: Learning is more effective if it’s real, relevant and practical. Set in situations that are familiar to learners, and acknowledging the nuance involved in their choices, makes the learning easier to transfer to the real world.

- Engagement: Humans respond well to emotionally impactful and memorable stories. A well-constructed realistic scenario will fuel a learner’s motivation. Realistic characters and a relevant storyline will keep learners engaged. They’ll want to find out what happens next and see the outcome of their choices.

- A safe space: Learners can make mistakes and take remedial action to recover in a safe online simulation. This approach can be used to explore situations that might be too risky, difficult, sensitive or expensive to explore in real life.

How to use scenario-based learning?

There are lots of ways to include scenarios in your elearning design, from quick and simple to longer-form and intricately designed.

So, where do you start?

- Understand your learning needs: Begin by understanding the problem you’re trying to solve and the audience you’re targeting. This will help you identify an approach that will resonate and create real business impact.

- Explore the critical situations: Speak to your colleagues and find out where and why work situations might prove challenging. Identify what triggers the event as this will be the starting point of your scenario.

- Identify the decision points: Walk through the work situation. Pinpoint the key decision points and the motivations behind these decisions. Identify the common mistakes that people make and the key feedback and reflection points that should be highlighted.

5 scenario-based elearning examples

Once you’ve analyzed your learning needs and outlined your scenario, it’s time to design your learning.

Here are five scenario-based elearning examples , each with a different approach , to get you inspired.

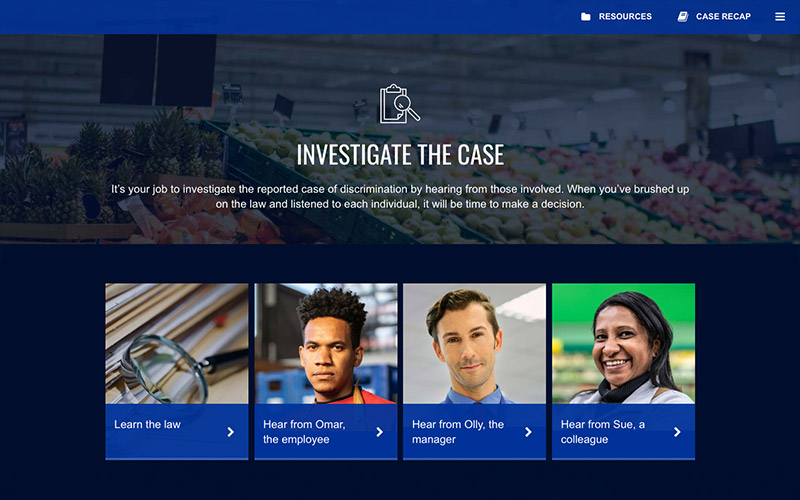

1. Scenario-based learning at scale

When working with a high volume of learners, small tweaks can make all the difference. By giving learners a range of choices to explore, this scenario based elearning example feels more relevant and personal to each individual. By allowing them to ‘work’ a case and draw their own conclusions they are drawn through the story and have autonomy in how they approach their learning.

Scenario-based learning example:

A great scenario-based approach for:

- Large organizations with multiple or diverse audiences in different environments

- Addressing nuanced topics where learners need to see several viewpoints. Think ethics training, discrimination or health and safety.

See this scale-friendly ele https://www.elucidat.com/showcase/#scenario-based-learning-at-scale arning example

2. Story as a way into the substance

A scenario can be a great way into a topic that is complex, dry or otherwise tricky. In this example, the story draws the learner in and primes them for the core content about ethical dilemmas and decision making.

Why it works:

- The (true) story has suspense and drama without being contrived or unbelievable, and music clips and engaging visuals bring it to life

- Decision points with immediate feedback in the narrator’s voice maintain immersion and the momentum of the story

- At the end, those low-stakes decisions are played back with commentary on what they might suggest about the learner’s responses in higher-stakes situations

- There is no judgment given – the scenario is all about drawing the learner in, prompting some self-reflection and priming them for the true learning content to come

- A low-tech interactive scenario makes a big, potentially daunting, topic accessible and engaging

Click here to go to this example

3. Product training using a sales simulation

When you need to train staff up on a new product, you could just give them the product information. But this elearning scenario example shows how taking a scenario-based approach to test that knowledge can be more engaging and more effective.

- Applying a simple scenario turns a basic multiple choice quiz into a more challenging simulation

- The quiz module tests the learner’s sales skills and ability to apply the learning in context, rather than simple recall of facts

- Using a customer scenario brings the content to life and helps to embed the product knowledge

- Feedback directs the learner back to the product information if the learner choose incorrectly, reinforcing the learning rather than just giving the correct answer

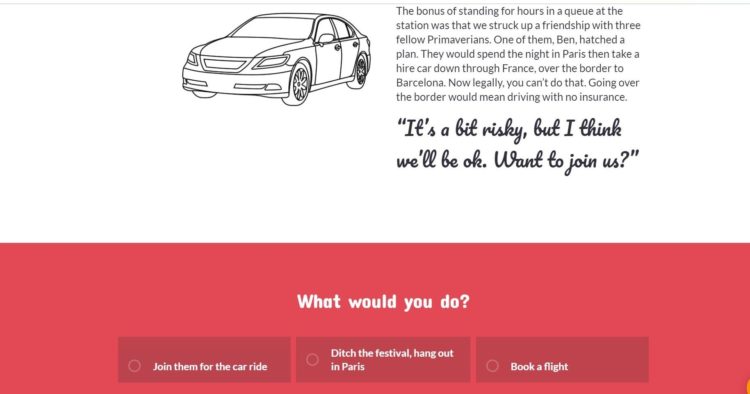

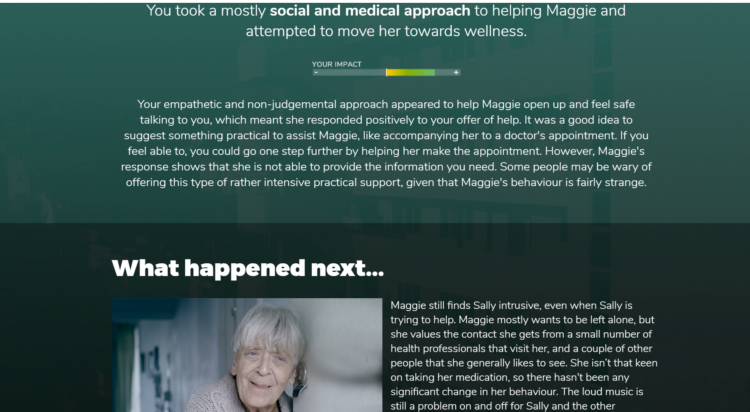

4. Immersive branching scenarios to explore consequences

Sometimes it pays to develop a more immersive, branching scenario – like this Open University example. This works really well when you want to offer experiential learning online and need the learner to engage emotionally with a subject.

- It combines Elucidat’s video players, rules, branching, social polls and layout designer to immerse the user in each emotionally-charged scenario

- The user learns by doing: their choices control the story and they see and feel the impact of their decisions on other people

- Feedback is offered at the end rather than incrementally after each decision point, so the branching is seamless and the story more realistic and engaging