ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, inclusive education: what it means, proven strategies, and a case study.

Considering the potential of inclusive education at your school? Perhaps you are currently working in an inclusive classroom and looking for effective strategies. Lean into this deep-dive article on inclusive education to gather a solid understanding of what it means, what the research shows, and proven strategies that bring out the benefits for everyone.

What is inclusive education? What does it mean?

Inclusive education is when all students, regardless of any challenges they may have, are placed in age-appropriate general education classes that are in their own neighborhood schools to receive high-quality instruction, interventions, and supports that enable them to meet success in the core curriculum (Bui, Quirk, Almazan, & Valenti, 2010; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

The school and classroom operate on the premise that students with disabilities are as fundamentally competent as students without disabilities. Therefore, all students can be full participants in their classrooms and in the local school community. Much of the movement is related to legislation that students receive their education in the least restrictive environment (LRE). This means they are with their peers without disabilities to the maximum degree possible, with general education the placement of first choice for all students (Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

Successful inclusive education happens primarily through accepting, understanding, and attending to student differences and diversity, which can include physical, cognitive, academic, social, and emotional. This is not to say that students never need to spend time out of regular education classes, because sometimes they do for a very particular purpose — for instance, for speech or occupational therapy. But the goal is this should be the exception.

The driving principle is to make all students feel welcomed, appropriately challenged, and supported in their efforts. It’s also critically important that the adults are supported, too. This includes the regular education teacher and the special education teacher , as well as all other staff and faculty who are key stakeholders — and that also includes parents.

The research basis for inclusive education

Inclusive education and inclusive classrooms are gaining steam because there is so much research-based evidence around the benefits. Take a look.

Benefits for students

Simply put, both students with and without disabilities learn more . Many studies over the past three decades have found that students with disabilities have higher achievement and improved skills through inclusive education, and their peers without challenges benefit, too (Bui, et al., 2010; Dupuis, Barclay, Holms, Platt, Shaha, & Lewis, 2006; Newman, 2006; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

For students with disabilities ( SWD ), this includes academic gains in literacy (reading and writing), math, and social studies — both in grades and on standardized tests — better communication skills, and improved social skills and more friendships. More time in the general classroom for SWD is also associated with fewer absences and referrals for disruptive behavior. This could be related to findings about attitude — they have a higher self-concept, they like school and their teachers more, and are more motivated around working and learning.

Their peers without disabilities also show more positive attitudes in these same areas when in inclusive classrooms. They make greater academic gains in reading and math. Research shows the presence of SWD gives non-SWD new kinds of learning opportunities. One of these is when they serve as peer-coaches. By learning how to help another student, their own performance improves. Another is that as teachers take into greater consideration their diverse SWD learners, they provide instruction in a wider range of learning modalities (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic), which benefits their regular ed students as well.

Researchers often explore concerns and potential pitfalls that might make instruction less effective in inclusion classrooms (Bui et al., 2010; Dupois et al., 2006). But findings show this is not the case. Neither instructional time nor how much time students are engaged differs between inclusive and non-inclusive classrooms. In fact, in many instances, regular ed students report little to no awareness that there even are students with disabilities in their classes. When they are aware, they demonstrate more acceptance and tolerance for SWD when they all experience an inclusive education together.

Parent’s feelings and attitudes

Parents, of course, have a big part to play. A comprehensive review of the literature (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2010) found that on average, parents are somewhat uncertain if inclusion is a good option for their SWD . On the upside, the more experience with inclusive education they had, the more positive parents of SWD were about it. Additionally, parents of regular ed students held a decidedly positive attitude toward inclusive education.

Now that we’ve seen the research highlights on outcomes, let’s take a look at strategies to put inclusive education in practice.

Inclusive classroom strategies

There is a definite need for teachers to be supported in implementing an inclusive classroom. A rigorous literature review of studies found most teachers had either neutral or negative attitudes about inclusive education (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2011). It turns out that much of this is because they do not feel they are very knowledgeable, competent, or confident about how to educate SWD .

However, similar to parents, teachers with more experience — and, in the case of teachers, more training with inclusive education — were significantly more positive about it. Evidence supports that to be effective, teachers need an understanding of best practices in teaching and of adapted instruction for SWD ; but positive attitudes toward inclusion are also among the most important for creating an inclusive classroom that works (Savage & Erten, 2015).

Of course, a modest blog article like this is only going to give the highlights of what have been found to be effective inclusive strategies. For there to be true long-term success necessitates formal training. To give you an idea though, here are strategies recommended by several research studies and applied experience (Morningstar, Shogren, Lee, & Born, 2015; Alquraini, & Gut, 2012).

Use a variety of instructional formats

Start with whole-group instruction and transition to flexible groupings which could be small groups, stations/centers, and paired learning. With regard to the whole group, using technology such as interactive whiteboards is related to high student engagement. Regarding flexible groupings: for younger students, these are often teacher-led but for older students, they can be student-led with teacher monitoring. Peer-supported learning can be very effective and engaging and take the form of pair-work, cooperative grouping, peer tutoring, and student-led demonstrations.

Ensure access to academic curricular content

All students need the opportunity to have learning experiences in line with the same learning goals. This will necessitate thinking about what supports individual SWDs need, but overall strategies are making sure all students hear instructions, that they do indeed start activities, that all students participate in large group instruction, and that students transition in and out of the classroom at the same time. For this latter point, not only will it keep students on track with the lessons, their non-SWD peers do not see them leaving or entering in the middle of lessons, which can really highlight their differences.

Apply universal design for learning

These are methods that are varied and that support many learners’ needs. They include multiple ways of representing content to students and for students to represent learning back, such as modeling, images, objectives and manipulatives, graphic organizers, oral and written responses, and technology. These can also be adapted as modifications for SWDs where they have large print, use headphones, are allowed to have a peer write their dictated response, draw a picture instead, use calculators, or just have extra time. Think too about the power of project-based and inquiry learning where students individually or collectively investigate an experience.

Now let’s put it all together by looking at how a regular education teacher addresses the challenge and succeeds in using inclusive education in her classroom.

A case study of inclusive practices in schools and classes

Mrs. Brown has been teaching for several years now and is both excited and a little nervous about her school’s decision to implement inclusive education. Over the years she has had several special education students in her class but they either got pulled out for time with specialists or just joined for activities like art, music, P.E., lunch, and sometimes for selected academics.

She has always found this method a bit disjointed and has wanted to be much more involved in educating these students and finding ways they can take part more fully in her classroom. She knows she needs guidance in designing and implementing her inclusive classroom, but she’s ready for the challenge and looking forward to seeing the many benefits she’s been reading and hearing about for the children, their families, their peers, herself, and the school as a whole.

During the month before school starts, Mrs. Brown meets with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez — and other teachers and staff who work with her students — to coordinate the instructional plan that is based on the IEPs (Individual Educational Plan) of the three students with disabilities who will be in her class the upcoming year.

About two weeks before school starts, she invites each of the three children and their families to come into the classroom for individual tours and get-to-know-you sessions with both herself and the special education teacher. She makes sure to provide information about back-to-school night and extends a personal invitation to them to attend so they can meet the other families and children. She feels very good about how this is coming together and how excited and happy the children and their families are feeling. One student really summed it up when he told her, “You and I are going to have a great year!”

The school district and the principal have sent out communications to all the parents about the move to inclusion education at Mrs. Brown’s school. Now she wants to make sure she really communicates effectively with the parents, especially as some of the parents of both SWD and regular ed students have expressed hesitation that having their child in an inclusive classroom would work.

She talks to the administration and other teachers and, with their okay, sends out a joint communication after about two months into the school year with some questions provided by the book Creating Inclusive Classrooms (Salend, 2001 referenced in Salend & Garrick-Duhaney, 2001) such as, “How has being in an inclusion classroom affected your child academically, socially, and behaviorally? Please describe any benefits or negative consequences you have observed in your child. What factors led to these changes?” and “How has your child’s placement in an inclusion classroom affected you? Please describe any benefits or any negative consequences for you.” and “What additional information would you like to have about inclusion and your child’s class?” She plans to look for trends and prepare a communication that she will share with parents. She also plans to send out a questionnaire with different questions every couple of months throughout the school year.

Since she found out about the move to an inclusive education approach at her school, Mrs. Brown has been working closely with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez, and reading a great deal about the benefits and the challenges. Determined to be successful, she is especially focused on effective inclusive classroom strategies.

Her hard work is paying off. Her mid-year and end-of-year results are very positive. The SWDs are meeting their IEP goals. Her regular ed students are excelling. A spirit of collaboration and positive energy pervades her classroom and she feels this in the whole school as they practice inclusive education. The children are happy and proud of their accomplishments. The principal regularly compliments her. The parents are positive, relaxed, and supportive.

Mrs. Brown knows she has more to learn and do, but her confidence and satisfaction are high. She is especially delighted that she has been selected to be a part of her district’s team to train other regular education teachers about inclusive education and classrooms.

The future is very bright indeed for this approach. The evidence is mounting that inclusive education and classrooms are able to not only meet the requirements of LRE for students with disabilities, but to benefit regular education students as well. We see that with exposure both parents and teachers become more positive. Training and support allow regular education teachers to implement inclusive education with ease and success. All around it’s a win-win!

Lilla Dale McManis, MEd, PhD has a BS in child development, an MEd in special education, and a PhD in educational psychology. She was a K-12 public school special education teacher for many years and has worked at universities, state agencies, and in industry teaching prospective teachers, conducting research and evaluation with at-risk populations, and designing educational technology. Currently, she is President of Parent in the Know where she works with families in need and also does business consulting.

You may also like to read

- Inclusive Education for Special Needs Students

- Teaching Strategies in Early Childhood Education and Pre-K

- Mainstreaming Special Education in the Classroom

- Five Reasons to Study Early Childhood Education

- Effective Teaching Strategies for Special Education

- 6 Strategies for Teaching Special Education Classes

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Curriculum and Instruction , High School (Grades: 9-12) , Middle School (Grades: 6-8) , Pros and Cons , Teacher-Parent Relationships , The Inclusive Classroom

- Online Education Specialist Degree for Teache...

- Online Associate's Degree Programs in Educati...

- Master's in Math and Science Education

Overview of Inclusive Teaching Practices

Main navigation.

We regard inclusive and equitable education as holistic and part of all learning, and so inclusive learning practices apply to many aspects of the learning experience throughout these guides.

The resources and strategies on this page act as a starting point for a wide variety of course design strategies, teaching practices, and support resources that all contribute towards an inclusive and equitable course.

Provide equitable access

Inclusive education is accessible: all students should be able to access the materials they need for their learning. While accessibility is often associated with providing access for people with disabilities, issues of access are universal and affect all learners. To develop a course that is inclusive for all, consider accessibility broadly and how it impacts everyone.

Accessibility takes many forms, including:

- Access to course materials for students with visual or hearing differences

- Access to technology tools, reliable connections, and consideration of international restrictions on technology use

- Affordability and the cost of course materials

- Temporal access for students juggling multiple priorities or in different time zones

- Access to multiple modalities regarding materials, activities, and learning assessments

The Equitable Access page has more details on these accessibility strategies.

Set norms and commitments

Collectively deciding on norms and making commitments for how students will interact with one another is an important step towards creating a respectful, supportive, and productive class learning environment.

Plan ahead before facilitating your norm setting activity with your students. There are many areas to consider for setting norms and commitments:

- Charged conversations or discussions of challenging topics

- Accountability, communication, and equitable work distribution during teamwork

- Peer review, feedback, and critique

- Office hours timing and modes of communication

- Online discussion forum expectations

- Managing video, minimizing distractions, and appropriate non-verbal communication in video conferencing

See the page on Setting Norms and Commitments for more specific strategies.

Build inclusive learning communities

Research into the social and emotional dimensions of learning suggests that a sense of social disconnection from instructors and peers can impede learning and that this disproportionately impacts underrepresented students. Deliberately fostering a classroom community and helping students connect with one another can help students feel seen and valued, which can have positive impacts on learning, especially during online instruction.

Consider these general strategies for fostering an inclusive learning community:

- Be conscious of visual and other cues that send implicit signals about who belongs and who can succeed.

- Build opportunities for student choice and agency into the course.

- Adopt caring practices to enhance student motivation.

- Foster community and connection at all stages of the course experience.

See the page on Building Inclusive Community for more details and links to additional resources.

Support students with disabilities

Faculty and teaching staff play an important role when a student requests or requires academic accommodation based on a disability.

Instructors can best support students and the Office of Accessible Education (OAE) by:

- Informing students of OAE and its services.

- Respecting students' privacy and being compassionate.

- Collaborating with OAE to modify and implement any recommended academic accommodation.

The Supporting Students with Disabilities page provides more details on how you can best work with OAE.

Facilitate inclusive and equitable discussions

Discussions are commonly used in actively engaged learning environments. These strategies can help to improve the quality of discussion in online as well as in-person formats:

- Support students when examining potentially upsetting content

- Use prompts or questions that elicit a variety of perspectives

- Adopt practices that ensure equitable participation

- Evaluate discussions along various dimensions

Go to Inclusive and Equitable Discussions for specific actions you can take to facilitate inclusive discussions.

Explore more inclusion and equity topics

The Teaching Commons Articles section offers a variety of additional resources organized under the Inclusion & Equity topic tag.

Equitable access

- Resources for Faculty & Teaching Staff , Office of Accessible Education (2020)

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL) , Schwab Learning Center (2020)

- Stanford-approved Learning Technology Tools , Learning Technologies & Spaces (2020)

- Stanford Online Accessibility Program (SOAP) , Online Accessibility Program (2020)

- Stanford University Library services , Stanford University Library (2020)

Norms and commitments

- Suggested norms for online classes , GSE IT Teaching Resources

- "Please, let students turn their videos off in class" , The Stanford Daily

- Class Community Commitments: A Guide for Instructors , Center for Teaching and Learning

- Stanford SPARQtools , Stanford SPARQ

Inclusive community

- CARE for Inclusion and Equity Online , Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning (2020)

- Community building activities for agreement and norm-setting , Stanford Graduate School of Education IT Teaching Resources (2020)

- Informal trust-building in an online environment , Stanford Graduate School of Education IT Teaching Resources (2020)

- Facilitating class community building before the quarter begins , Stanford Graduate School of Education Information Technology Teaching Resources (2020)

- Stanford SPARQtools , Stanford SPARQ (2020)

Accommodations for students with disabilities

- Office of Accessible Education (OAE) , Stanford University (2020)

- Diversity and Access Office , Stanford University (2020)

Inclusive and equitable discussions

- 10 Strategies for Engaging Discussions Online , Center for Teaching and Learning (2020)

- Successful breakout rooms in Zoom , Teaching Commons (2020)

- Small group activities for Zoom breakout rooms , Teaching Commons (2020)

- Strive for JUSTICE in Course Learning , Center for Teaching and Learning (2020)

- 2020 GEM REPORT

- Inclusion and education

- Monitoring SDG 4

- Recommendations

- 2020 Webpage

- Press Release

- RELATED PUBLICATIONS

- Gender Report

- Youth Report

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Central and Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia

- Background papers

- Statistical Tables

- 2019 Report

- 2017/8 Report

- 2016 Report

2020 GEM Report

Plan International Australia

- Full Report

- 2020 webpage

Introduction

The commitment of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) to ensure ‘inclusive and equitable quality education’ and promote ‘lifelong learning for all’ is part of the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development pledge to leave no one behind. The agenda promises a ‘just, equitable, tolerant, open and socially inclusive world in which the needs of the most disadvantaged are met’.

Social, economic and cultural factors may complement or run counter to the achievement of equity and inclusion in education. Education offers a key entry point for inclusive societies if it sees learner diversity not as a problem but as a challenge: to identify individual talent in all shapes and forms and create conditions for it to flourish. Unfortunately, disadvantaged groups are kept out or pushed out of education systems through more or less subtle decisions leading to exclusion from curricula, irrelevant learning objectives, stereotyping in textbooks, discrimination in resource allocation and assessments, tolerance of violence and neglect of needs.

Contextual factors, such as politics, resources and culture, can make the inclusion challenge appear to vary across countries or groups. In reality, the challenge is the same, regardless of context. Education systems need to treat every learner with dignity in order to overcome barriers, raise attainment and improve learning. Systems need to stop labelling learners, a practice adopted on the pretext of easing the planning and delivery of education responses. Inclusion cannot be achieved one group at a time (Figure 1). Learners have multiple, intersecting identities. Moreover, no one characteristic is associated with any predetermined ability to learn.

FIGURE 1: The one thing we all have in common is our differences

Inclusion in education is first and foremost a process.

Inclusion is for all. Inclusive education is commonly associated with the needs of people with disabilities and the relationship between special and mainstream education. Since 1990, the struggle of people with disabilities has shaped the global perspective on inclusion in education, leading to recognition of the right to inclusive education in Article 24 of the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). However, as General Comment No. 4 on the article recognized in 2016, inclusion is broader in scope. The same mechanisms exclude not only people with disabilities but also others on account of gender, age, location, poverty, disability, ethnicity, indigeneity, language, religion, migration or displacement status, sexual orientation or gender identity expression, incarceration, beliefs and attitudes. It is the system and context that do not take diversity and multiplicity of needs into account, as the Covid-19 pandemic has also laid bare. It is society and culture that determine rules, define normality and perceive difference as deviance. The concept of barriers to participation and learning should replace the concept of special needs.

Inclusion is a process. Inclusive education is a process contributing to achievement of the goal of social inclusion. Defining equitable education requires a distinction between ‘equality’ and ‘equity’. Equality is a state of affairs (what): a result that can be observed in inputs, outputs or outcomes. Equity is a process (how): actions aimed at ensuring equality. Defining inclusive education is more complicated because process and result are conflated. This Report argues for thinking of inclusion as a process: actions that embrace diversity and build a sense of belonging, rooted in the belief that every person has value and potential, and should be respected, regardless of their background, ability or identity. Yet inclusion is also a state of affairs, a result, which the CRPD and General Comment No. 4 stopped short of defining with precision, likely because of differing views of what the result should be.

INCLUSION IN EDUCATION AS RESULT: START WITH EDUCATION FOR ALL

Poverty and inequality are major constraints. Despite progress in reducing extreme poverty, especially in Asia, it affects 1 in 10 adults and 2 in 10 children – 5 in 10 in sub-Saharan Africa. Income inequality is growing in parts of the world or, if falling, remains unacceptably high among and within countries. Key human development outcomes are also unequally distributed. In 30 low- and middle-income countries, 41% of children under age 5 from the poorest 20% of households were malnourished, more than twice the rate of those from the richest 20%, severely compromising their opportunity to benefit from education.

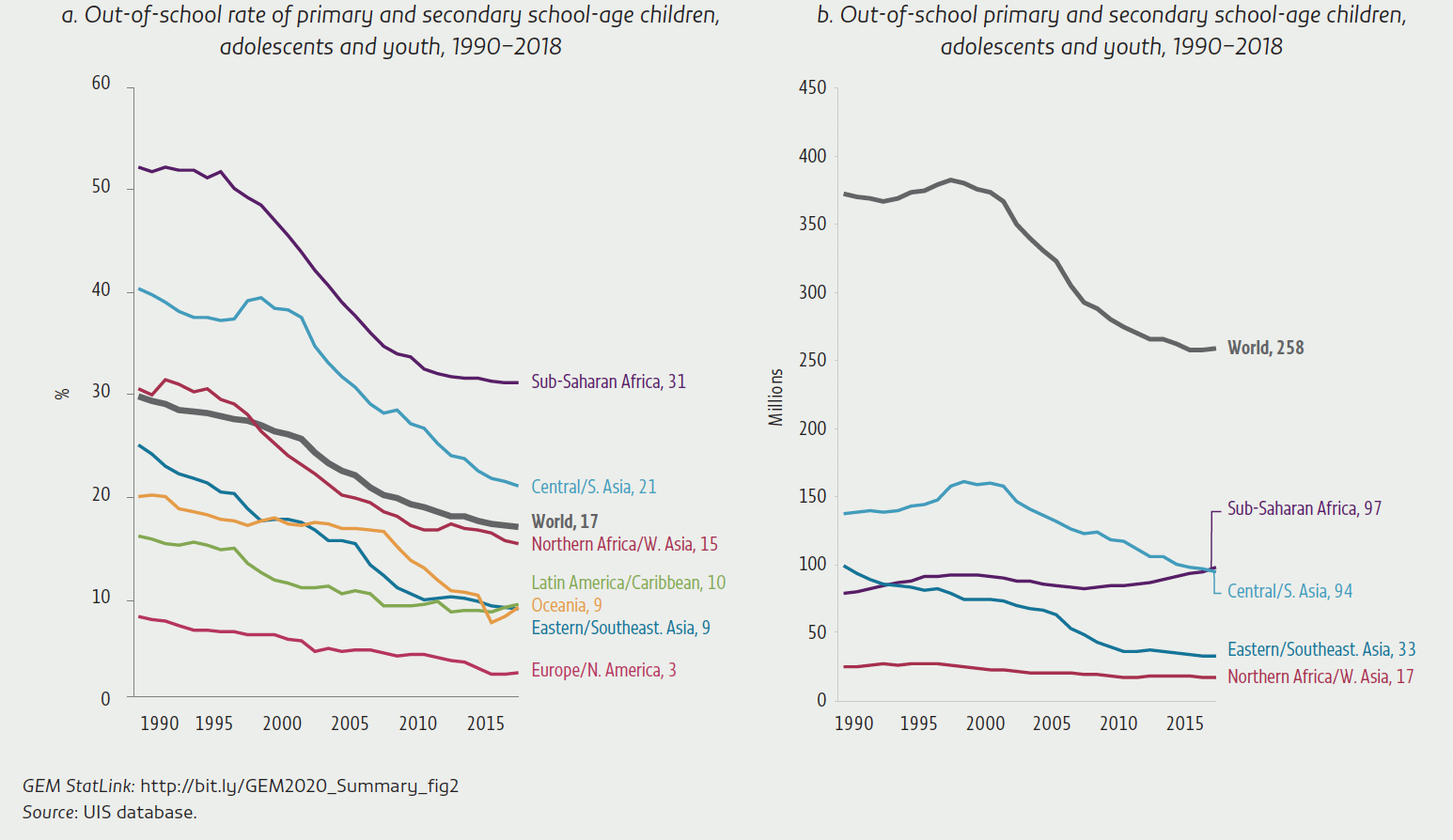

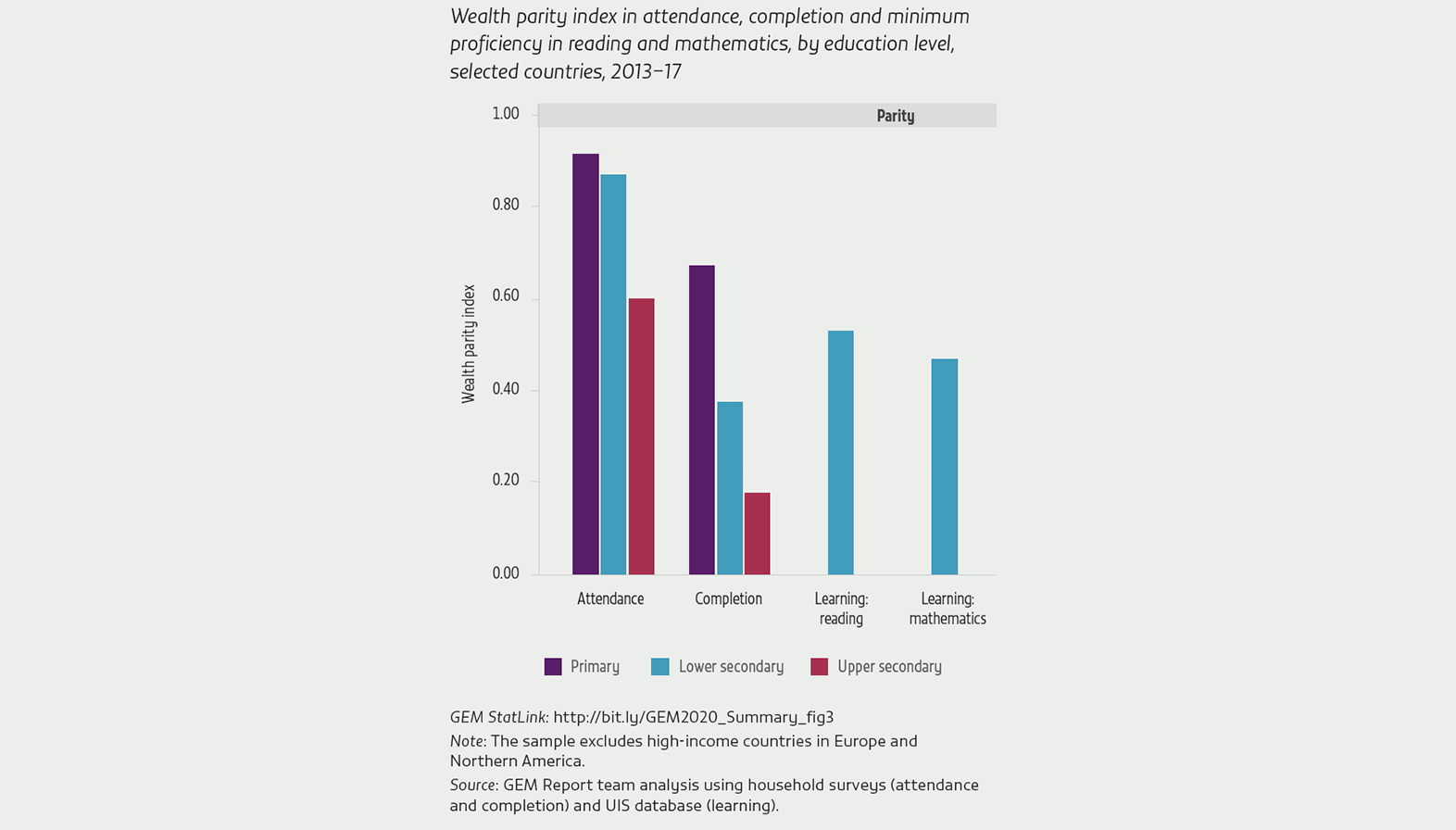

Progress in education participation is stagnating. An estimated 258 million children, adolescents and youth, or 17% of the total, are not in school (Figure 2). Disparities by wealth in attendance rates are large: Among 65 low-and middle-income countries, the average gap in attendance rates between the poorest and the richest 20% of households was 9 percentage points for primary school-age children, 13 for lower secondary school-age adolescents and 27 for upper secondary school-age youth. As the poorest are more likely to repeat and leave school early, wealth gaps are even higher in completion rates: 30 percentage points for primary, 45 for lower secondary and 40 for upper secondary school completion.

Poverty affects attendance, completion and learning opportunities. In all regions except Europe and Northern America, for every 100 adolescents from the richest 20% of households, 87 from the poorest 20% attended lower secondary school and 37 completed it. Of the latter, for every 100 adolescents from the richest 20% of households, about 50 achieved minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics (Figure 3). Often, disadvantages intersect. Those most likely to be excluded from education are also disadvantaged due to language, location, gender and ethnicity. In at least 20 countries with data, hardly any poor rural young woman completed upper secondary school.

FIGURE 2: A quarter of a billion children, adolescents and youth are not in school

FIGURE 3: There are large wealth disparities in attendance, completion and learning

THE RESULTS OF INCLUSION IN EDUCATION MAY BE ELUSIVE, BUT ARE REAL, NOT ILLUSIVE

While universal access to education is a prerequisite for inclusion, there is less consensus on what else it means to achieve inclusion in education for learners with disabilities and other disadvantaged groups at risk of exclusion.

Inclusion for students with disabilities means more than placement. The CRPD focus on school placement marked a break not just with the historical tendency to exclude children with disabilities from education or to segregate them in special schools but also with the practice of putting them in separate classes for much or most of the time. Inclusion, however, involves many more changes in school support and ethos. The CRPD did not argue special schools violated the convention, but recent reports by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities increasingly point in that direction. The CRPD gave governments a free hand in the form of inclusive education, implicitly recognizing the obstacles to full inclusion. While exclusionary practices by many governments that contravene their CRPD commitments should be exposed, the limits to how flexible mainstream schools and education systems can be should also be acknowledged.

Inclusive education serves multiple objectives. There is a potential tension between the desirable goals of maximizing interaction with others (all children under the same roof and fulfilling learning potential (wherever students learn best. Other considerations include the speed with which systems can move towards the ideal and what happens during transition, and the trade-off between early needs identification and the risk of labelling and stigmatization.

Pursuing different objectives simultaneously can be complementary or conflicting. Policymakers, legislators and educators confront delicate and context-specific questions related to inclusion. They need to be aware of opposition by those invested in preserving segregated delivery but also of the potential unsustainability of rapid change, which can harm the welfare of those it is meant to serve. Including children with disabilities in mainstream schools that are not prepared, supported or accountable for achieving inclusion can intensify experiences of exclusion and provoke backlash against making schools and systems more inclusive.

There can be downsides to full inclusion. In some contexts, inclusion may inadvertently intensify pressure to conform. Group identities, practices, languages and beliefs may be devalued, jeopardized or eradicated, undercutting a sense of belonging. The right for a group to preserve its culture and the right to self-determination and self-representation are increasingly recognized. Inclusion may be resisted out of prejudice but also out of recognition that identity may be maintained and empowerment achieved only if a minority is a majority in a given area. Rather than achieve positive social engagement, in some circumstances inclusion policies may exacerbate social exclusion. Exposure to the majority may reinforce dominant prejudices, intensifying minority disadvantage. Targeting assistance can also lead to stigmatization, labelling or unwelcome forms of inclusion.

Resolving dilemmas requires meaningful participation. Inclusive education should be based on dialogue, participation and openness. While policymakers and educators should not compromise, discount or divert from the long-term ideal of inclusion, they should not override the needs and preferences of those affected. Fundamental human rights and principles provide moral and political direction for education decisions, yet fulfilling the inclusive ideal is not trivial. Delivering sufficient differentiated and individualized support requires perseverance, resilience and a long-term perspective. Moving away from education system design that suits some children and obliges others to adapt cannot easily happen by decree. Prevailing attitudes and mindsets must be challenged. Inclusive education may prove intractable, even with the best will and highest commitment. Some, therefore, argue for limiting the ambition of inclusive education, but the only way forward is to acknowledge the barriers and dismantle them.

Inclusion brings benefits. Careful planning and provision of inclusive education can deliver improvement in academic achievement, social and emotional development, self-esteem and peer acceptance. Including diverse students in mainstream classrooms and schools can prevent stigma, stereotyping, discrimination and alienation. There are also potential efficiency savings from eliminating parallel education structures and using resources more effectively in a single inclusive mainstream system. However, economic justification for inclusive education, while valuable for planning, is not sufficient. Few systems come close enough to the ideal to allow estimation of the full cost, and benefits are hard to quantify, as they extend over generations.

Inclusion is a moral imperative. Debating the benefits of inclusive education is akin to debating the benefits of human rights. Inclusion is a prerequisite for sustainable societies. It is a prerequisite for education in, and for, a democracy based on fairness, justice and equity. It provides a systematic framework for removing barriers according to the principle ‘every learner matters and matters equally’. It also counteracts education system tendencies that allow exceptions and exclusions, as when schools are evaluated along a single dimension and resource allocation is linked to their performance.

Inclusion improves learning for all students. In recent years, a learning crisis narrative has drawn attention to the majority of school-age children in low- and middle-income countries not achieving minimum proficiency in basic skills. However, this narrative may overlook dysfunctional features of education systems in the countries furthest behind, such as exclusion, elitism and inequity. It is not by accident that SDG 4 explicitly exhorts countries to ensure inclusive education. Mechanical solutions that do not address the deeper barriers of exclusion can only go so far towards improving learning outcomes. Inclusion must be the foundation of approaches to teaching and learning.

The 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report asks questions related to key policy solutions, obstacles to implementation, coordination mechanisms, financing channels and monitoring of inclusive education. To the extent possible, it examines these questions in view of change over time. However, an area as complex as inclusion has not yet been well documented on a global scale. This Report collects information on how each country, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, addresses the challenge of inclusion in education. The information is available on a new website, PEER , which countries can use to share experiences and learn from one another, especially at the regional level, where contexts are similar. The profiles can serve as a baseline to review qualitative progress to 2030.

The Report recognizes the different contexts and challenges facing countries in providing inclusive education; the various groups at risk of being excluded from education and the barriers individual learners face, especially when characteristics intersect; and the fact that exclusion can be physical, social (in interpersonal and group relations, psychological and systemic. It addresses these challenges through seven elements in respective chapters, while a short section highlights how these challenges have played out in the context of Covid-19.

Laws and policies

Binding legal instruments and non-binding declarations express international aspirations for inclusion. The 1960 UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education and the 1990 World Declaration on Education for All, adopted in Jomtien, Thailand, called on countries to take measures to ensure ‘equality of treatment in education’ and no ‘discrimination in access to learning opportunities’ for ‘underserved groups’. The 1994 Statement and Framework for Action adopted in Salamanca, Spain, put forward the principle that all children should be at ‘the school that would be attended if the child did not have a disability’, which was endorsed as a right in 2006. These texts have influenced the national laws and policies on which progress towards inclusion hinges.

National definitions of inclusive education tend to embrace a broader scope. Analysis for this Report shows that 68% of countries define inclusive education in laws, policies, plans or strategies. Definitions that cover all marginalized groups are found in 57% of countries. In 17% of countries, the definition of inclusive education covers exclusively people with disabilities or special needs. ( PEER ).

Laws tend to target specific groups at risk of exclusion in education. The broad vision of including all learners in education is largely absent from national laws. Only 10% of countries reflected comprehensive provisions for all learners in their general or inclusive education laws. More commonly, legislation originating in education ministries concerns specific groups. Of all countries, 79% had laws referring to education for people with disabilities, 60% for linguistic minorities, 50% for gender equality and 49% for ethnic and indigenous groups. ( PEER ).

Policies tend to have a broader vision of inclusion in education. About 17% of countries have policies containing comprehensive provisions for all learners. The tendency is much stronger in less binding texts, with 75% of national education plans and strategies declaring an intention to include all disadvantaged groups. Some 67% of countries have policies on inclusion of learners with disabilities, with responsibility for these policies almost equally split between education ministries and other ministries. ( PEER )

Laws and policies differ on whether students with disabilities should be in mainstream schools. Laws in 25% of countries provide for education in separate settings, with shares exceeding 40% in Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean. About 10% of countries mandate integration and 17% inclusion, the remainder opting for combinations of segregation and mainstreaming. Policies have shifted closer to inclusion: 5% of countries have policy provisions for education in separate settings, while 12% opt for integration and 38% for inclusion. Despite the good intentions enshrined in laws and policies, governments often do not ensure implementation.

Policies need to be consistent and coherent across ages and education levels. Access to early childhood care and education is highly inequitable, conditioned by location and socio-economic status. Quality, especially interactions, integration, and child-centredness based on play, also determines inclusion. Early identification of children’s needs is crucial to designing the right responses, but labels of difference in the name of inclusion can misfire. Disproportionately assigning some marginalized groups to special needs categories can indicate discriminatory procedures, as successful legal challenges over Roma students’ right to education demonstrate.

Preventing early school leaving requires policies on multiple fronts. Education systems face a dilemma. Grade retention appears to increase dropout, but automatic promotion requires systematic approaches to remedial support, which many countries proclaim but fail to implement. Laws and policies may not be consistent with inclusion, e.g. in countries with low child labour or marriage age thresholds. Bangladesh is among the few countries to invest extensively in second-chance programmes, which are indispensable for achieving SDG 4.

Governments are striving to make post-compulsory and adult education policies more inclusive. Technical and vocational education can facilitate labour market inclusion of vulnerable groups, notably young women and people with disabilities. Unlocking its potential requires making learning environments safer and accessible, as in Malawi. Inclusion-oriented tertiary education interventions tend to focus on encouraging access for disadvantaged groups through quotas or affordability measures. Yet only 11% of 71 countries had comprehensive equity strategies; another 11% elaborated approaches only for particular groups. Digital inclusion, especially of the elderly, is a major challenge for countries increasingly dependent on information and communication technology (ICT).

Responses to the Covid-19 crisis, which affected 1.6 billion learners, have not paid sufficient attention to including all learners. While 55% of low-income countries opted for online distance learning in primary and secondary education, only 12% of households in least developed countries have internet access at home. Even low-technology approaches cannot ensure learning continuity. Among the poorest 20% of households, just 7% owned a radio in Ethiopia and none owned a television. Overall, about 40% of low- and lower-middle-income countries have not supported learners at risk of exclusion. In France, up to 8% of students had lost contact with teachers after three weeks of lockdown.

Data on and for inclusion in education are essential. Data on inclusion can highlight gaps in education opportunities and outcomes among learner groups, identifying those at risk of being left behind and the severity of the barriers they face. Using such information, governments can develop policies for inclusion and collect further data on implementation and on less easily observed qualitative outcomes.

Formulating appropriate questions on characteristics associated with vulnerability can be sensitive. Data on education disparity at the population level, collected through censuses and surveys, raise education ministries’ awareness of disparity. However, depending on their formulation, questions on characteristics such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity expression can touch on sensitive personal identities, be intrusive and trigger persecution fears.

The formulation of questions on disability has improved. Agreeing to a valid measure of disability has been a long process . The UN Statistical Commission’s Washington Group on Disability Statistics proposed a short set of questions for censuses or surveys in 2006, covering critical functional domains and activities for adults. A child-specific module was then developed with UNICEF. The questions bring disability statistics in line with the social model of disability and resolve serious comparability issues. Their rate of adoption is only slowly picking up.

The evidence that emerges on disability is of higher quality but still patchy. Analysis of 14 countries taking part in the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) in 2017–19 and using the wider child-specific module showed a disability prevalence of 12%, ranging from 6% to 24%, as a result of high anxiety and depression rates. Across these countries, children, adolescents and youth with disabilities accounted for 15% of the out-of-school population. Relative to their peers of primary, lower secondary and upper secondary school age, those with a disability were more likely to be out of school by 1, 4 and 6 percentage points, respectively, and those with a sensory, physical or intellectual disability by 4, 7 and 11 percentage points.

Some school surveys provide deeper insights into inclusion. In the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), one in five 15-year-old students reported feeling like an outsider at school, but the share exceeded 30% in Brunei Darussalam, the Dominican Republic and the United States. In all participating education systems, students of lower socio-economic status were less likely to feel a sense of belonging. Administrative data can be leveraged to collect qualitative evidence on inclusion. New Zealand systematically monitors soft indicators at the national level, including on whether students feel cared for, safe and secure, and on their ability to establish and maintain positive relationships, respect others’ needs and show empathy. Almost half of low- and middle-income countries collect no administrative data on students with disabilities.

Data show where segregation is still taking place. In Brazil, a policy change increased the share of students with disabilities in mainstream schools from 23% in 2003 to 81% in 2015. In Asia and the Pacific, almost 80% of children with disabilities attended mainstream schools, from 3% in Kyrgyzstan to 100% in Timor-Leste and Thailand. Scattered data record schools catering to specific groups, such as girls, linguistic minorities and religious communities. Their contribution to inclusion is ambiguous: Indigenous schools, for instance, can provide an environment where traditions, cultures and experiences are respected, but they can also perpetuate marginality. School surveys such as PISA show high levels of socio-economic segregation in countries including Chile and Mexico, where half of all students would require school reassignment to achieve a uniform socio-economic mix. This type of school segregation barely changed over 2000–15.

Identification of special education needs can be contentious. Identification can inform teachers about student needs so they can target support and accommodation. Yet children could be reduced to labels by peers, teachers and administrators, which can prompt stereotyped behaviours towards labelled students and encourage a medical approach. Portugal recently legislated a non-categorical approach to determining special needs. Low expectations triggered by a label, such as having learning difficulties, can become self-fulfilling. In Europe, the share of students identified with special education needs ranged from 1% in Sweden to 20% in Scotland. Learning disability was the largest category of special needs in the United States but was unknown in Japan. Such variation is mainly explained by differences in how countries construct this category of education: Institution, funding and training requirements vary, as do policy implications.

Governance and finance

Ensuring inclusive education is not the sole responsibility of education policy actors. Integrating services can improve the way children’s needs are considered, as well as services’ quality and cost-effectiveness. Integration can be achieved when one service provider acts as a referral point for access to another. A mapping of inclusive education provision in 18 European countries, mostly with reference to students with disabilities, showed education ministries responsible for teachers, school administration and learning materials; health ministries for screening, assessment and rehabilitation services; and social protection ministries for financial aid.

Sharing responsibility does not guarantee horizontal collaboration, cooperation and coordination. Deep-rooted norms, traditions and bureaucratic working cultures hinder smooth transition away from siloed forms of service delivery. Insufficient resources may also be a factor: In Kenya, one-third of county-level Educational Assessment Resource Centres, set up to expand access to education for children with disabilities, had one officer instead of the multidisciplinary teams envisaged. Clearly defined, measurable standards outlining responsibilities are needed. Rwanda developed standards enabling inspectors to assess classroom inclusivity. In Jordan, various actors used separate standards for licensing and accrediting special education centres; the new 10-year strategy will address this issue.

Vertical integration among government tiers and support to local government are needed. Central governments must fund commitments to local governments fully and develop their capacity. A Republic of Moldova reform to move children out of mostly state boarding schools stumbled because savings were not transferred to the local government institutions and schools absorbing the children. In Nepal, a midterm evaluation of the school sector programme and the first inclusive education workshop showed that, while some central government posts were shifted as part of decentralization, local government capacity to support education service delivery was weak.

Three funding levers are important for equity and inclusion in education. First, governments may or may not compensate for relative disadvantage in allocating resources to local authorities or schools through capitation grants. Argentina’s federal government allocates block grants to provincial governments, taking rural and out-of-school populations into account. Provinces co-finance education from their revenue, whose levels vary greatly, contributing to inequality. Second, education financing policies and programmes may target students and their families in the form of cash (e.g. scholarships) and exemptions from payment (e.g. fees). About one in four countries have affirmative action programmes for access to tertiary education. Third, non-education-specific financing policies and programmes can have a large impact on education. Over the long term, conditional cash transfers in Latin America increased education attainment by between 0.5 and 1.5 years.

Financing disability-inclusive education requires additional focus. A twin-track approach to financing is recommended, complementing general mechanisms with targeted programmes. Policymakers need to define standards for services to be delivered and the costs they will cover. They need to address the challenge of expanding costs as special needs identification rates increase, and design ways to prioritize, finance and deliver targeted services for a wide range of needs. They also need to define results in a way that maintains pressure on local authorities and schools to avoid further earmarking services for children with diagnosed special needs and further segregating settings at the expense of other groups or general financing needs. Finland has been moving in this direction.

Even richer countries lack information on financing education for students with disabilities. A project mapping European countries’ financing of inclusive education found that only 5 in 18 had relevant information. There is no ideal funding mechanism, since countries vary in history, understanding of inclusive education and levels of decentralization. A few countries are moving away from multiple weights (e.g. by type of impairment), which may inflate the number of students identified with special needs, to a simple funding formula for mainstream schools. Many promote networks to share resources, facilities and capacity development opportunities.

Poorer countries often struggle to finance the shift from special to inclusive education. Some countries have increased their budgets to improve inclusion of students with disabilities. The 2018/19 Mauritius budget quadrupled the annual per capita grant for teaching aids, utilities, furniture and equipment for students with special needs.

Curricula, textbooks and assessments

Curriculum choices can promote or obstruct an inclusive and democratic society. Curricula need to reassure all groups at risk of exclusion that they are fundamental to the education project, whether in terms of content or implementation. Using different curricula of differing standards for some groups hinders inclusion and creates stigma. Yet many countries still teach students with disabilities a special curriculum, offer refugees only the curriculum of their home country to encourage repatriation, and tend to push lower achievers onto slower education tracks. Challenges arise in several contexts: internally displaced populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina; gender issues in Peru; linguistic minorities in Thailand; Burundian and Congolese refugees in the United Republic of Tanzania; indigenous peoples in Canada. In Europe, 23 in 49 countries did not address sexual orientation and gender identity expression explicitly.

Inclusive curricula need to be relevant, flexible and responsive to needs. Evidence from citizen-led assessments in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa highlighted large gaps between curriculum objectives and learning outcomes. When curricula cater to more privileged students and certain types of knowledge, implementation inequality between rural and urban areas arises, as a curriculum study of primary mathematics in Uganda showed. Learning in the mother tongue is vital, especially in primary school, to avoid knowledge gaps and increase the speed of learning and comprehension. In India’s Odisha state, multilingual education covered about 1,500 primary schools and 21 tribal languages of instruction. Just 41 countries worldwide recognize sign language as an official language, of which 21 are in the European Union. In Australia, 19% of students receive adjustments to the curriculum. Curricula should not lead to dead ends in education but offer pathways for continuous education opportunities.

Textbooks can perpetuate stereotypes. Representation of ethnic, linguistic, religious and indigenous minorities in textbooks depends largely on historical and national context. Factors influencing countries’ treatment of minorities include the presence of indigenous populations; the demographic, political or economic dominance of one or more ethnic groups; the history of segregation or conflict; the conceptualization of nationhood; and the role of immigration. Textbooks may acknowledge minority groups in ways that mitigate or exacerbate the degree to which they are perceived, or perceive themselves, as ‘other’. Inappropriate images and descriptions that associate certain characteristics with particular population groups can make students with non-dominant backgrounds feel misrepresented, misunderstood, frustrated and alienated. In many countries, females are often under-represented and stereotyped. The share of females in secondary school English language textbook text and images was 44% in Indonesia, 37% in Bangladesh and 24% in Punjab province, Pakistan. Women were represented in less prestigious occupations and as introverted.

Good-quality assessments are a fundamental part of an inclusive education system. Assessments are often organized unduly narrowly, determining admission to certain schools or placement in separate school tracks, and sending conflicting signals about government commitment to inclusion. Large-scale, cross-national summative assessments, for instance, tend to exclude students with disabilities or learning difficulties. Assessment should focus on students’ tasks: how they tackle them, which ones prove difficult and how some aspects can be adapted to enable success. A shift in emphasis from high-stake summative assessments at the end of the education cycle to low-stake formative assessments over the education trajectory underpins efforts to make assessment fit for the purpose of inclusive education. Test accommodations are essential, but their validity has been questioned in that they appear to fit students to a model. The emphasis should instead be on how the assessment can support students with impairments in demonstration of their learning. In seven sub-Saharan African countries, no teacher had minimum knowledge in student assessment.

Various factors need to be aligned for inclusive curricular, textbook and assessment reforms. Capacity needs to be developed so stakeholders can work collaboratively and think strategically. Partnerships need to be in place to enable all parties to own the process and work towards the same goals. Successful attempts to make curricula, textbooks and assessments inclusive entail participatory processes during design, development and implementation.

Teachers and education support personnel

In inclusive education, all teachers should be prepared to teach all students. Inclusion cannot be realized unless teachers are agents of change, with values, knowledge and attitudes that permit every student to succeed. Teachers’ attitudes often mix commitment to the principle of inclusion with doubts about their preparedness and how ready the education system is to support them. Teachers may not be immune to social biases and stereotypes. Inclusive teaching requires teachers to be open to diversity and aware that all students learn by connecting classroom with life experiences. While many teacher education and professional learning opportunities are designed accordingly, entrenched views of some students as deficient, unable to learn or incapable mean teachers may struggle to see that each student’s learning capacity is open-ended.

Lack of preparedness for inclusive teaching may result from gaps in pedagogical knowledge. Some 25% of teachers in the 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey reported a high need for professional development in teaching students with special needs. Across 10 francophone sub-Saharan African countries, 8% of grade 2 and 6 teachers had received in-service training in inclusive education. Overcoming the legacy of preparing different types of teachers for different types of students in separate settings is important. To be of good quality, teacher education must cover multiple aspects of inclusive teaching for all learners, from instructional techniques and classroom management to multi-professional teams and learning assessment methods, and should include follow-up support to help teachers integrate new skills into classroom practice. In Canada’s New Brunswick province, a comprehensive inclusive education policy introduced training opportunities for teachers to support students with autism spectrum disorders.

Teachers need appropriate working conditions and support to adapt teaching to student needs. In Cambodia, teachers questioned the feasibility of applying child-centred pedagogy in a context of overcrowded classrooms, scarce teaching resources and overambitious curricula. Teaching to standardized content requirements of a learning assessment can make it more difficult for teachers to adapt their practice. Cooperation among teachers in different schools can support them in addressing the challenges of diversity, especially in systems transitioning from segregation to inclusion. Sometimes such collaboration is absent even among teachers at the same school. In Sri Lanka, few teachers in mainstream classes collaborated with peers in special needs units.

A rise in support personnel accompanied the mainstreaming of students with special needs. Yet, globally, provision is lacking. Respondents to a survey of teacher unions reported that support personnel were largely absent or not available in at least 15% of countries. Classroom learning or teaching assistants can be particularly helpful. However, while their role is to supplement teachers’ work, they are often put in positions that demand much more. Increased professional expectations, accompanied by often low levels of professional development, can lead to lower-quality learning, interference with peer interaction, decreased access to competent instruction, and stigmatization. In Australia, access of students with disabilities to qualified teachers was partly impeded by the system’s overdependence on unqualified support personnel.

Teacher diversity often lags behind population diversity. This is sometimes the result of structural problems preventing members of marginalized groups from acquiring qualifications, teaching in schools once they are qualified and remaining in the profession. Systems should recognize that these teachers can bolster inclusion by offering unique insights and serving as role models to all students. In India, the share of teachers from scheduled castes, which constitute 16% of the country’s population, increased from 9% to 13% between 2005 and 2013.

Inclusion in education requires inclusive schools. School ethos – the explicit and implicit values and beliefs, as well as the interpersonal relationships, that define a school’s atmosphere – has been linked to students’ social and emotional development and well-being. The share of students in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries who felt they ‘belonged’ in school fell from 82% in 2003 to 73% in 2015 due to increasing shares of students with immigrant backgrounds and declining levels of a sense of belonging among natives.

Head teachers can foster a shared vision of inclusion. They can guide inclusive pedagogy and plan professional development activities. A cross-country study of teachers of special needs students in mainstream schools found that those who received more instructional leadership reported lower professional development needs. While head teachers’ tasks are increasingly complex, nearly one-fifth (rising to half in Croatia) had no instructional leadership training. Across 47 education systems, 15% of head teachers (rising to more than 60% in Viet Nam) reported a high need for professional development in promoting equity and diversity.

School bullying and violence cause exclusion. One-third of 11- to 15-year-olds have been bullied in school. Those perceived as differing from social norms or ideals are the most likely to be victimized, including sexual, ethnic and religious minorities, the poor and those with special needs. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex students in New Zealand were three times as likely to be bullied. In Uganda, 84% of children with disabilities versus 53% of those without experienced violence by peers or staff. Classroom management practices, guidance services and policies should identify staff responsibilities and actions to prevent and address bullying and violence. Punitive approaches should not displace student support and cultivation of a respectful atmosphere.

Schools must be safe and accessible. Transit to school, building design and sanitation facilities often violate accessibility, acceptability and adaptability principles. More than one-quarter of girls in 11 African, Asian and Latin American countries reported never or seldom feeling safe on the way to or from school. No schools in Burundi, Niger and Samoa had ‘adapted infrastructure and materials for students with disabilities’. In Slovakia, 15% of primary and 21% of lower secondary schools met such standards. Reliable comparable evidence remains elusive because countries’ standards vary and schools do not meet all elements of a standard; in addition, monitoring capacity is weak and data are not independently verified.

Accessible infrastructure often does not support all. The CRPD called for universal design to increase functionality and accommodate everyone’s needs, regardless of age, size or ability. Incorporating full-access facilities from the outset increases cost by 1%, compared with 5% or more after completion. Aid programmes helped disseminate universal design principles. Indonesian schools built with Australian support included accessible toilets, handrails and ramps; the government adopted similar measures for all new schools.

Assistive technology can determine participation or marginalization. Assistive devices refer to input technology (adapted keyboards and computer input controls, speech input, dictation software) and output technology (screen readers and magnifiers, three-dimensional printers, Braille note-takers). Alternative and augmentative communication systems replace speech. Assistive listening systems improve sound clarity and reduce background noise. Such technology improves graduation rates, self-esteem and optimism, but is often unavailable due to lack of resources or not used effectively due to lack of teacher education.

Students, parents and communities

Take marginalized students’ experiences into account. Documenting disadvantaged students’ views without singling them out is difficult. Their inclusion preferences are shown to depend on their vulnerability, type of school attended, experience at a different type of school, and the level and discreetness of specialized support. Vulnerable students in mainstream schools may appreciate separate settings for the sake of increased attention or reduced noise. Pairing students with peers with disabilities can increase acceptance and empathy, although it does not guarantee inclusion outside school.

Majority populations tend to stereotype minority and marginalized students. Negative attitudes lead to less acceptance, isolation and bullying. Syrian refugees in Turkey felt negative stereotypes led to depression, stigmatization and alienation from school. Stereotypes can lower students’ expectations and self-esteem. In Switzerland, girls internalized the view that they are less suited than boys for science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which discouraged them from pursuing degrees in these fields. Teachers can fight but also perpetuate discrimination in education. Mathematics teachers in São Paulo, Brazil, were more likely to pass white students than their equally proficient and well-behaved black classmates. Teachers in China had less favourable perceptions of rural migrant students than of their urban peers.

Parents drive but also resist inclusive education. Parents may hold discriminatory beliefs about gender, disability, ethnicity, race or religion. Some 15% in Germany and 59% in Hong Kong, China, feared that children with disabilities disturbed others’ learning. Given choice, parents wish to send their vulnerable children to schools that ensure their well-being. They need to trust mainstream schools to respond to their needs. As school becomes more demanding with age, parents of children with autism spectrum disorders may have to look for schools that better meet their needs. In Australia’s Queensland state, 37% of students in special schools had moved from mainstream schools.

Parental school choice affects inclusion and segregation. Families with choice may avoid disadvantaged local schools. In Danish cities, a seven percentage point increase in the share of migrant students was associated with a one percentage point increase in the share of natives attending private school. In Lebanon, the majority of parents favoured private schools along sectarian lines. In Malaysia, private school streams organized by ethnicity and differentiated by quality contributed to stratification, despite government measures to desegregate schools. The potential of distance and online mainstream education for inclusion notwithstanding, parental preference for self-segregation through homeschooling tests the limits of inclusive education.

Parents of children with disabilities often find themselves in a distressing situation. Parents need support in early identification and management of their children’s sleep, behaviour, nursing, comfort and care. Early intervention programmes can help them grow confident, use other support services and enrol children in mainstream schools. Mutual support programmes can provide solidarity, confidence and information. Parents with disabilities are more likely to be poor, less educated and face barriers coming to school or working with teachers. In Viet Nam, children of parents with disabilities had 16% lower attendance rates.

Civil society has been advocate and watchdog for the right to inclusive education. Organizations for people with disabilities, disabled people’s organizations, grassroots parental associations and international non-government organizations (NGOs) active in development and education monitor progress on government commitments, campaign for fulfilment of rights and defend against violations of the right to inclusive education. In Armenia, an NGO campaign resulted in a legal and budget framework for rolling out inclusive education nationally by 2025.

Civil society groups provide education services on government contract or their own initiative. These services may support groups governments do not reach (e.g. street children) or be alternatives to government services. The Ghana Inclusive Education Policy calls on NGOs to mobilize resources, advocate for increased funding, contribute to infrastructure development and engage in monitoring and evaluation. The Afghanistan government supports community-based education, which relies on local people. Yet NGO schools set up for specific groups may promote segregation rather than inclusion in education. They should align with policy and not replicate services or compete for limited funds.

Education in the other SDGs

The goals of gender equality, climate change and partnerships have large and unrealized synergies with education. A review of effective means of combating climate change ranked girls’ and women’s education and family planning sixth and seventh out of 80 solutions. The review estimated that filling the GEM Report-estimated financing gap of US$39 billion a year could yield a reduction of 51 gigatons of emissions by 2050, an ‘incalculable’ return on investment. Indigenous peoples and local communities manage at least 17% of the total carbon stored in forest lands in 52 tropical and subtropical countries, making protecting their knowledge vital. As of 2017, 102 of 195 UNESCO member states had a designated education focal point for Action for Climate Empowerment to support provision of climate change mitigation education.

While gender is a cross-cutting priority in all multi-stakeholder funding partnerships, connections between education and climate change are weaker. There has been no clear targeting from global climate finance in 2015–16 for scaling up education systems and girls’ education, for behavioural changes in food waste and diet, or for indigenous approaches to land use and management.

Search the United Nations

- Independent side events

- FAQs - General

- FAQs - Logistics

- Vision Statement

- Consultations

- International Finance Facility for Education

- Gateways to Public Digital Learning

- Youth Engagement

- Youth Declaration

- Education in Crisis Situations

- Addressing the Learning Crisis

- Transform the World

- Digital Learning for All

- Advancing Gender Equality

- Financing Education

Why inclusive education is important for all students

Truly transformative education must be inclusive. The education we need in the 21st century should enable people of all genders, abilities, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds and ages to develop the knowledge, skills and attitudes required for resilient and caring communities. In light of pandemics, climate crises, armed conflict and all challenges we face right now, transformative education that realizes every individual’s potential as part of society is critical to our health, sustainability, peace and happiness.

To achieve that vision, we need to take action at a systemic level. If we are to get to the heart of tackling inequity, we need change to our education systems as a whole, including formal, non-formal and informal education spaces .

I grew up in the UK in the 1990s under a piece of legislation called Section 28 . This law sought to “ prohibit the promotion of homosexuality ” and those behind it spoke a lot about the wellbeing of children. However, this law did an immense amount of harm, as bullying based on narrow stereotypes of what it meant to be a girl or a boy became commonplace and teachers were disempowered from intervening. Education materials lacked a diversity of gender representation for fear of censure, and as a result, children weren’t given opportunities to develop understanding or empathy for people of diverse genders and sexualities.

I have since found resonance with the term non-binary to describe my gender, but as an adolescent, what my peers saw was a disabled girl who did not fit the boxes of what was considered acceptable. Because of Section 28, any teacher’s attempts to intervene in the bullying were ineffective and, lacking any representation of others like me, I struggled to envisage my own future. Section 28 was repealed in late 2003; however, change in practice was slow, and I dropped out of formal education months later, struggling with my mental health.

For cisgender (somebody whose gender identity matches their gender assigned at birth) and heterosexual girls and boys, the lack of representation was limiting to their imaginations and created pressure to follow certain paths. For LGBTQ+ young people, Section 28 was systemic violence leading to psychological, emotional and physical harm. Nobody is able to really learn to thrive whilst being forced to learn to survive. Psychological, emotional and physical safety are essential components of transformative education.

After dropping out of secondary school, I found non-formal and informal education spaces that gave me the safety I needed to recover and the different kind of learning I needed to thrive. Through Guiding and Scouting activities, I found structured ways to develop not only knowledge, but also important skills in teamwork, leadership, cross-cultural understanding, advocacy and more. Through volunteering, I met adults who became my possibility models and enabled me to imagine not just one future but multiple possibilities of growing up and being part of a community.

While I found those things through non-formal and informal education spaces (and we need to ensure those forms of education are invested in), we also need to create a formal education system that gives everyone the opportunity to aspire and thrive.

My work now, with the Kite Trust , has two strands. The first is a youth work programme giving LGBTQ+ youth spaces to develop the confidence, self-esteem and peer connections that are still often lacking elsewhere. The second strand works with schools (as well as other service providers) to help them create those spaces themselves. We deliver the Rainbow Flag Award which takes a whole-school approach to inclusion. The underlying principle is that, if you want to ensure LGBTQ+ students are not being harmed by bullying, it goes far beyond responding to incidents as they occur. We work with schools to ensure that teachers are skilled in this area, that there is representation in the curriculum, that pastoral support in available to young people, that the school has adequate policies in place to ensure inclusion, that the wider community around the school are involved, and that (most importantly) students are given a meaningful voice.

This initiative takes the school as the system we are working to change and focuses on LGBTQ+ inclusion, but the principles are transferable to thinking about how we create intersectional, inclusive education spaces in any community or across society as a whole. Those working in the system need to be knowledgeable in inclusive practices, the materials used and content covered needs to represent diverse and intersectional experiences and care needs to be a central ethos. All of these are enabled by inclusive policy making, and inclusive policy making is facilitated by the involvement of the full range of stakeholders, especially students themselves.

If our communities and societies are to thrive in the face of tremendous challenges, we need to use these principles to ensure our education systems are fully inclusive.

Pip Gardner (pronouns: They/them) is Chief Executive of the Kite Trust, and is a queer and trans activist with a focus on youth empowerment. They are based in the UK and were a member of the Generation Equality Youth Task Force from 2019-21.

A Journey to the Stars

Isabel’s journey to pursue education in Indigenous Guatemala

School was a safe place: How education helped Nhial realize a dream

- News: IITE and partners in action

Inclusive education through the prism of the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report

On July 10, UNESCO IITE hosted a webinar on the 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report and the presentation of the country profile of the Russian Federation. Two weeks earlier, the GEM Report team officially launched its 2020 GEM Report on inclusion . Invited experts and those responsible for the education policy in the Russian Federation participated in the webinar, as well as the international expert on the policy analysis.

Presentation of the 2020 GEM Report

At the opening of the webinar Director of UNESCO IITE Tao Zhan noted that inclusion in education is a very important and challenging theme during the pandemic and for the future of education systems. Moreover, this is a key area where it is necessary to apply advanced digital technologies and strengthen the cooperation of all partners. The Senior Policy Analyst of the GEM Report team supported this message by highlighting the main issues and tasks, which the Report outlined.

We need to see learner diversity not as a problem, but as an opportunity. Inclusion cannot be achieved if it is seen as an inconvenience or if people harbour the belief that children’s capacity to learn is fixed. Stigma, stereotypes and discrimination mean millions are alienated inside classrooms meaning they are less likely to progress through education. – Bilal Barakat, Senior Policy Analyst of the GEM Report team, UNESCO

The country profile of the Russian Federation

The country profiles immensely contributed to the Report by providing the results of the analysis on the inclusive education in different countries. UNESCO IITE together with the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN) prepared the country profile of the Russian Federation. It covers the key points of inclusion and regulatory mechanisms at the state level and in the constituent entities. The analysis was carried out in 5 areas: the definition of inclusive education; laws, policies and programs; management and finance; teachers and supporting staff; data and monitoring.

As a result, the report presents the outcomes of an analytical study highlighting the key issues of the implementation of inclusive education policies. In the process of the preparation, we sought to cover all the mechanisms that could lead children, youth and adults to the exclusion from education. Moreover, we described the situation taking into account 4 characteristics: gender, disability, poverty, ethnicity and language. – Natalia Amelina, Senior National Project Officer in Education, UNESCO IITE

Inclusive education in action