The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Pre-revolutionary france, nation and society.

Bibliography

The modern concept of nationalism does not consider its long history and the difference in cultural and political contexts. One of the most developed variants of this concept is the nationalism of the era of the French Revolution. Nationalism then gave meaning to a substantial political movement against the monarchy and helped shape modern France culturally, ideologically, and politically. Nationalism as a cultural concept matured in French literature and philosophy, becoming related to religion in terms of meanings. In 1789, with the outbreak of the French Revolution, the idea of nationalism spread throughout France, forming a new ideology and structure of society that adhered to the values of freedom, equality, and fraternity. The rise of nationalism within France, as it played heavily during the French Revolution, is considered hereafter.

By 1789, an absolute monarchy had developed in France during the life of Louis XVI. He, in turn, relied on an extensive bureaucracy, a vast apparatus of officials, and a regular army. France’s entire political and cultural life revolved around the family of the ruler and his associates. Louis XVI behaved wastefully, and boldly, and showed complete ignorance of ordinary citizens’ affairs and France’s economic problems. Against the backdrop of absolute monarchy in 1788, unemployment developed among the working class and peasants who worked in the silk weaving industry and were engaged in harvesting 1 . The general mental state of the citizens was depressive since France of those years reflected only the royal family’s life. The impression was that ordinary people felt isolated and deprived of the opportunity to express themselves. It is how the pre-revolutionary crisis developed, which raised a wave of French nationalism. The economic background made a quiet life of people impossible since they could neither work, trade nor pay royal taxes.

Realizing this, Louis XVI makes the first concessions and begins to consult with the assembly of notables. The assembled group included aristocrats, whom the king usually only notified of his will but did not consult and did not entrust the solution to significant problems. Meanwhile, in 1789, a political crisis can be traced against the backdrop of an economic one, and Louis XVI convened the Estates General 2 . The Estates General is a representative body of power, incredibly responsible to citizens for innovations, particularly economic ones. It is an elected body, which eventually caused an unexpected stir among the peasants and the bourgeoisie, who wanted to participate in the country’s political life and put forward their demands. The peasants opposed payments, significant taxes, and levies and declared discrimination from feudal lords and seigneurs in their direction. The bourgeoisie demanded the abolition of censorship and restrictions on trade and industry.

It should be noted that the bourgeoisie was the stronghold of the ideas of the Enlightenment, which played a critical role in forming a new French ideology based on nationalism. The opening of the Estates General in the spring of 1789 made it possible for the people to feel their influence on matters of state 3 . The people felt united because they made efforts to solve everyday problems. Nevertheless, Louis XVI treated the Estates General condescendingly and lightly, considering them only as an auxiliary situational body for solving economic issues. Inspired people, seeing each other’s discontent and realizing for the first time overcoming fragmentation, began to act.

The French Enlightenment became the backbone for creating the ideology of nationalism. Then the concept of nationalism was inextricably linked with society itself, and some philosophers did not separate these two concepts. However, historical and political events have reformed the linguistic meaning of the word. The views of Jean-Jacques Rousseau became central to the formation of the ideology of the French Revolution. Thanks to his works and other authors, France’s concept of nation and nationalism was quickly intellectualized while becoming the property of the peasants, not the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, and the upper class.

Having defined the nation, Jean-Jacques Rousseau took up the difficult task of educating and instilling new moral and intellectual values. The ideological awareness of the nation begins at a moment of crisis and dispute, where all people understand the possibilities of unification 4 . Nationalism was understood by Jean-Jacques Rousseau exclusively as cultural and political. A nation is a formed independent unit because it needs a state. And this state should personify the nation and be in close contact with it. In the monarchical rule, this was not possible since, under the absolute power of Louis XVI, the French were separated from France. Louis XVI became the face of France; in contrast, France as a state became the only manifestation of the power of Louis XVI and his family.

The nationalist revolution took place in France because the people became the sole referent for the actions carried out by the revolutionaries. This revolution was carried out for the people and at the hands of the people, who had ideological enemies that prevented them from gaining freedom. A nation could live only by politics, and politics was the only way to manifest national aspirations 5 . Nevertheless, according to the ideologists of the French Revolution, the final formation of the nation takes place only after the revolution’s victory, even though the revolutionary struggle is closely connected with nationalism.

The theoretical justification for the nationalism of the revolution lies in the term of the sovereign. In monarchical countries, the sovereign is the king and his family, and the closest associates may also partially have the sovereign status 6 . The king is the guarantor of sovereignty and its most striking manifestation. That is why a king’s assassination or natural death (especially in the Middle Ages) was perceived as a severe blow and a possible end to statehood in monarchical countries. As a result of the revolution, and even at the moment of the revolution, the nation becomes sovereign. It is the central meaning of French nationalism and revolutionary mood. It is in the hands of the nation that the main forces and potential of the state are concentrated. The sovereign nation decides its future; its members are intellectually and morally developed, consistent, intelligent, and robust.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau develops before the revolution the theory of the social contract and the term of the civil religion, which is the list of ideologies in which the nation sincerely believes. Such a religion may be unique for each nation member in detail, but its coordinates, as a whole, should be general 7 . Thus, the French nation has chosen as its ideologemes freedom, the ideals of equality and support for each other, that is, fraternity. This ideology consistently shaped the revolutionary and post-revolutionary French society and later became a household name for democratic ideologies. Initially, however, the Rousseauist concept was far from what people now understand by democracy: the state’s rule under the people’s will. The Rousseauian concept was based on a confrontation with the monarchy and did not imply, at that particular time, a well-coordinated system of elections and multi-stage voting. In the 1780s, there were strict voting qualifications, which allowed only men over 25 years old, and this system was supported by many people, not only supporters of Louis XVI and the monarchy in general.

The separation of society and nation was controversial, but this issue was clarified by the end of the French Revolution. Jean-Jacques Rousseau and other thinkers have tended to see the nation as a profoundly political term 8 . Society cannot fight political enemies for the future and freedom. In a way, French people are the most rigid and not active, unlike the nation 9 . Thus, the French community has always existed and cohabited with Louis XVI and his extravagance. However, the French nation was able to rally and bring the king to trial and execution.

Society thus retains inequality and can be divided into estates and castes, like the Indian system. According to the convention of the Jacobin Club, the nation is based on people’s equality and the struggle for this equality 10 . It is the primary meaning of egalitarianism, including the radical one. Having defeated the enemy in a brutal, bloody battle, nations deserve equality on various principles, from origin to professional affiliation and education. The system of lords, who subordinated the peasants, was overcome through tough reforms against the backdrop of the revolution. This feudal-communal system with an unequal distribution of wealth, manual labor for low pay, and extortions became one of the foundations of the French crisis in the heyday of Louis XVI.

The theoreticians of the French Revolution and nationalism took in the education of the social masses, who were then the majority uneducated. Instead of social tension, in the 1780s, there was an atmosphere of general acceptance of each other for overthrowing the absolute monarchy 11 . Feeling deceived by Louis XVI and the nobility, it seemed to people that they could only rely on each other, even if many of them did not understand anything about politics. Thus, representative bodies were organized that people could trust. In the late 1780s, a change in feudal legislation began with an improvement in the position of the peasants.

The most significant change was the judicial reform of the same years because, under the absolute monarchy, the court (both the main and the small district courts) became utterly subject to the personal will of Louis XVI. The courts ceased to fulfill their direct duties and lost their practical meaning; therefore, the Estates General decided to change this system entirely 12 . Cruelty throughout all the years of the revolution only reinforced people’s confidence in each other and the correctness of the professed views. Thus, people who achieved civic consciousness against the backdrop of violent events turned French society into a politically engaged nation with their claims, desires, and plans for the future.

Nationalism during the French Revolution became a stronghold of social restructuring and civic consciousness. United against the enemy, the absolute monarchy, people, despite the lack of education, managed to believe in the ideals of the Enlightenment and take part in creating new authorities that they trusted. The developed nationalist ideology was based on the models of pedagogy, culture, and humanistic maturation and helped to solve the fundamental economic problems caused by the wasteful rule of Louis XVI.

Armstrong, John. Nations Before Nationalism . UNC Press Books, 2017.

Barron, Alexander et al. “Individuals, Institutions, and Innovation in the Debates of the French Revolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115.18 (2018): 4607-4612.

Carlyle, Thomas. The French Revolution . Oxford University Press, 2019.

Connely, Owen. The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era . Harcourt. 2000.

Greenfeld, Liah. Nationalism: A Short History . Brookings Institution Press, 2019.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract . Independently published, 2020.

- Carlyle, Thomas. The French Revolution . Oxford University Press, 2019. 77.

- Greenfeld, Liah. Nationalism: A Short History . Brookings Institution Press, 2019, 54.

- Connely, Owen. The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era . Harcourt. 2000. 81-82.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract . Independently published, 2020, 24-26.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract . Independently published, 2020, 49.

- Armstrong, John. Nations Before Nationalism . UNC Press Books, 2017, 60-61.

- Connely, Owen. The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era . Harcourt. 2000, 100.

- Armstrong, John. Nations Before Nationalism . UNC Press Books, 2017. 111-112.

- Barron, Alexander et al. “Individuals, Institutions, and Innovation in the Debates of the French Revolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115.18 (2018): 4608.

- Philosophy and Society of Early Modern West

- Bildung Tradition and Kantian Philosophy

- Justice of Execution of R. Ludman & King Louis XVI

- French Revolution in World History

- "The Social Contract" by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- The Parliamentary Reform of the Church of England in the 19th Century

- The Reformation Era of 1517-1648

- Nationalism in Austria, Germany and Italy

- The Roman Empire and the Roman Republic

- The Second Industrial Revolution in Europe Before 1914

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, June 19). The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-nationalism-role-during-the-french-revolution/

"The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution." IvyPanda , 19 June 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-nationalism-role-during-the-french-revolution/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution'. 19 June.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution." June 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-nationalism-role-during-the-french-revolution/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution." June 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-nationalism-role-during-the-french-revolution/.

IvyPanda . "The Nationalism Role During the French Revolution." June 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-nationalism-role-during-the-french-revolution/.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

7 Key Figures of the French Revolution

These people played integral roles in the uprising that swept through France from 1789‑1799.

The French Revolution Was Plotted on a Tennis Court

Explore some well‑known “facts” about the French Revolution—some of which may not be so factual after all.

The Notre Dame Cathedral Was Nearly Destroyed By French Revolutionary Mobs

In the 1790s, anti‑Christian forces all but tore down one of France’s most powerful symbols—but it survived and returned to glory.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

How Bread Shortages Helped Ignite the French Revolution

When Parisians stormed the Bastille in 1789 they weren't only looking for arms, they were on the hunt for more grain—to make bread.

How a Scandal Over a Diamond Necklace Cost Marie Antoinette Her Head

The Diamond Necklace Affair reads like a fictional farce, but it was all true—and would become the final straw that led to demands for the queen's head.

How Versailles’ Over‑the‑Top Opulence Drove the French to Revolt

The palace with more than 2,000 rooms featured elaborate gardens, fountains, a private zoo, roman‑style baths and even 18th‑century elevators.

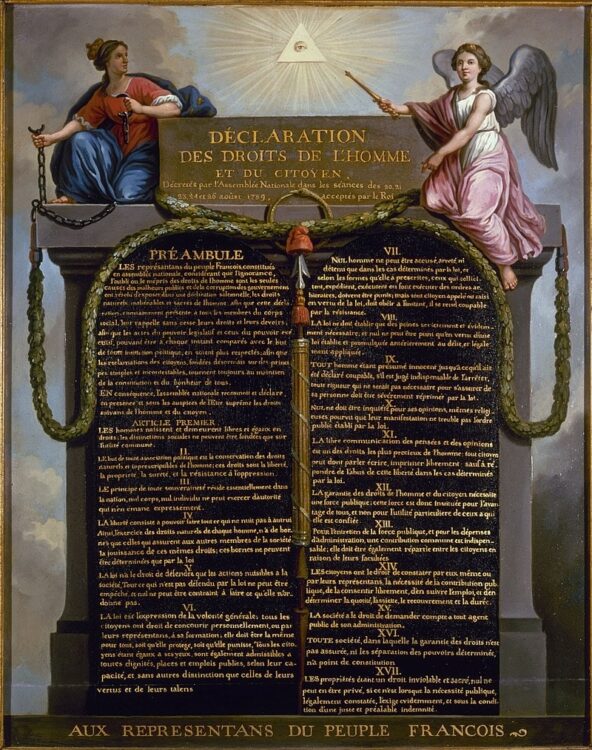

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History Cooperative

French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes

The French Revolution, a seismic event that reshaped the contours of political power and societal norms, began in 1789, not merely as a chapter in history but as a dramatic upheaval that would influence the course of human events far beyond its own time and borders.

It was more than a clash of ideologies; it was a profound transformation that questioned the very foundations of monarchical rule and aristocratic privilege, leading to the rise of republicanism and the concept of citizenship.

The causes of this revolution were as complex as its outcomes were far-reaching, stemming from a confluence of economic strife, social inequalities, and a hunger for political reform.

The outcomes of the French Revolution, embedded in the realms of political thought, civil rights, and societal structures, continue to resonate, offering invaluable insights into the power and potential of collective action for change.

Table of Contents

Time and Location

The French Revolution, a cornerstone event in the annals of history, ignited in 1789, a time when Europe was dominated by monarchical rule and the vestiges of feudalism. This epochal period, which spanned a decade until the late 1790s, witnessed profound social, political, and economic transformations that not only reshaped France but also sent shockwaves across the continent and beyond.

Paris, the heart of France, served as the epicenter of revolutionary activity , where iconic events such as the storming of the Bastille became symbols of the struggle for freedom. Yet, the revolution was not confined to the city’s limits; its influence permeated through every corner of France, from bustling urban centers to serene rural areas, each witnessing the unfolding drama of revolution in unique ways.

The revolution consisted of many complex factions, each representing a distinct set of interests and ideologies. Initially, the conflict arose between the Third Estate, which included a diverse group from peasants and urban laborers to the bourgeoisie, and the First and Second Estates, made up of the clergy and the nobility, respectively.

The Third Estate sought to dismantle the archaic social structure that relegated them to the burden of taxation while denying them political representation and rights. Their demands for reform and equality found resonance across a society strained by economic distress and the autocratic rule of the monarchy.

As the revolution evolved, so too did the nature of the conflict. The initial unity within the Third Estate fractured, giving rise to factions such as the Jacobins and Girondins, who, despite sharing a common revolutionary zeal, diverged sharply in their visions for France’s future.

The Jacobins , with figures like Maximilien Robespierre at the helm, advocated for radical measures, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, while the Girondins favored a more moderate approach.

The sans-culottes , representing the militant working-class Parisians, further complicated the revolutionary landscape with their demands for immediate economic relief and political reforms.

The revolution’s adversaries were not limited to internal factions; monarchies throughout Europe viewed the republic with suspicion and hostility. Fearing the spread of revolutionary fervor within their own borders, European powers such as Austria, Prussia, and Britain engaged in military confrontations with France, aiming to restore the French monarchy and stem the tide of revolution.

These external threats intensified the internal strife, fueling the revolution’s radical phase and propelling it towards its eventual conclusion with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who capitalized on the chaos to establish his own rule.

READ MORE: How Did Napoleon Die: Stomach Cancer, Poison, or Something Else?

Causes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution’s roots are deeply embedded in a confluence of political, social, economic, and intellectual factors that, over time, eroded the foundations of the Ancien Régime and set the stage for revolutionary change.

At the heart of the revolution were grievances that transcended class boundaries, uniting much of the nation in a quest for profound transformation.

Economic Hardship and Social Inequality

A critical catalyst for the revolution was France’s dire economic condition. Fiscal mismanagement, costly involvement in foreign wars (notably the American Revolutionary War), and an antiquated tax system placed an unbearable strain on the populace, particularly the Third Estate, which bore the brunt of taxation while being denied equitable representation.

Simultaneously, extravagant spending by Louis XVI and his predecessors further drained the national treasury, exacerbating the financial crisis.

The social structure of France, rigidly divided into three estates, underscored profound inequalities. The First (clergy) and Second (nobility) Estates enjoyed significant privileges, including exemption from many taxes, which contrasted starkly with the hardships faced by the Third Estate, comprising peasants , urban workers, and a rising bourgeoisie.

This disparity fueled resentment and a growing demand for social and economic justice.

Enlightenment Ideals

The Enlightenment , a powerful intellectual movement sweeping through Europe, profoundly influenced the revolutionary spirit. Philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu criticized traditional structures of power and authority, advocating for principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Their writings inspired a new way of thinking about governance, society, and the rights of individuals, sowing the seeds of revolution among a populace eager for change.

Political Crisis and the Estates-General

The immediate catalyst for the French Revolution was deeply rooted in a political crisis, underscored by the French monarchy’s chronic financial woes. King Louis XVI, facing dire fiscal insolvency, sought to break the deadlock through the convocation of the Estates-General in 1789, marking the first assembly of its kind since 1614.

This critical move, intended to garner support for financial reforms, unwittingly set the stage for widespread political upheaval. It provided the Third Estate, representing the common people of France, with an unprecedented opportunity to voice their longstanding grievances and demand a more significant share of political authority.

The Third Estate, comprising a vast majority of the population but long marginalized in the political framework of the Ancien Régime, seized this moment to assert its power. Their transformation into the National Assembly was a monumental shift, symbolizing a rejection of the existing social and political order.

The catalyst for this transformation was their exclusion from the Estates-General meeting, leading them to gather in a nearby tennis court. There, they took the historic Tennis Court Oath, vowing not to disperse until France had a new constitution.

This act of defiance was not just a political statement but a clear indication of the revolutionaries’ resolve to overhaul French society.

Amidst this burgeoning crisis, the personal life of Marie Antoinette , Louis XVI’s queen, became a focal point of public scrutiny and scandal.

Married to Louis at the tender age of fourteen, Marie Antoinette, the youngest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, was known for her lavish lifestyle and the preferential treatment she accorded her friends and relatives.

READ MORE: Roman Emperors in Order: The Complete List from Caesar to the Fall of Rome

Her disregard for traditional court fashion and etiquette, along with her perceived extravagance, made her an easy target for public criticism and ridicule. Popular songs in Parisian cafés and a flourishing genre of pornographic literature vilified the queen, accusing her of infidelity, corruption, and disloyalty.

Such depictions, whether grounded in truth or fabricated, fueled the growing discontent among the populace, further complicating the already tense political atmosphere.

The intertwining of personal scandals with the broader political crisis highlighted the deep-seated issues within the French monarchy and aristocracy, contributing to the revolutionary fervor.

As the political crisis deepened, the actions of the Third Estate and the controversies surrounding Marie Antoinette exemplified the widespread desire for change and the rejection of the Ancient Régime’s corruption and excesses.

Key Concepts, Events, and People of the French Revolution

As the Estates General convened in 1789, little did the world know that this gathering would mark the beginning of a revolution that would forever alter the course of history.

Through the rise and fall of factions, the clash of ideologies, and the leadership of remarkable individuals, this era reshaped not only France but also set a precedent for future generations.

From the storming of the Bastille to the establishment of the Directory, each event and figure played a crucial role in crafting a new vision of governance and social equality.

Estates General

When the Estates General was summoned in May 1789, it marked the beginning of a series of events that would catalyze the French Revolution. Initially intended as a means for King Louis XVI to address the financial crisis by securing support for tax reforms, the assembly instead became a flashpoint for broader grievances.

Representing the three estates of French society—the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners—the Estates General highlighted the profound disparities and simmering tensions between these groups.

The Third Estate, comprising 98% of the population but traditionally having the least power, seized the moment to push for more significant reforms, challenging the very foundations of the Ancient Régime.

The deadlock over voting procedures—where the Third Estate demanded votes be counted by head rather than by estate—led to its members declaring themselves the National Assembly, an act of defiance that effectively inaugurated the revolution.

This bold step, coupled with the subsequent Tennis Court Oath where they vowed not to disperse until a new constitution was created, underscored a fundamental shift in authority from the monarchy to the people, setting a precedent for popular sovereignty that would resonate throughout the revolution.

Rise of the Third Estate

The Rise of the Third Estate underscores the growing power and assertiveness of the common people of France. Fueled by economic hardship, social inequality, and inspired by Enlightenment ideals, this diverse group—encompassing peasants, urban workers, and the bourgeoisie—began to challenge the existing social and political order.

Their transformation from a marginalized majority into the National Assembly marked a radical departure from traditional power structures, asserting their role as legitimate representatives of the French people. This period was characterized by significant political mobilization and the formation of popular societies and clubs, which played a crucial role in spreading revolutionary ideas and organizing action.

This newfound empowerment of the Third Estate culminated in key revolutionary acts, such as the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a symbol of royal tyranny. This event not only demonstrated the power of popular action but also signaled the irreversible nature of the revolutionary movement.

The rise of the Third Estate paved the way for the abolition of feudal privileges and the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , foundational texts that sought to establish a new social and political order based on equality, liberty, and fraternity.

A People’s Monarchy

The concept of a People’s Monarchy emerged as a compromise in the early stages of the French Revolution, reflecting the initial desire among many revolutionaries to retain the monarchy within a constitutional framework.

This period was marked by King Louis XVI’s grudging acceptance of the National Assembly’s authority and the enactment of significant reforms, including the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the Constitution of 1791, which established a limited monarchy and sought to redistribute power more equitably.

However, this attempt to balance revolutionary demands with monarchical tradition was fraught with difficulties, as mutual distrust between the king and the revolutionaries continued to escalate.

The failure of the People’s Monarchy was precipitated by the Flight to Varennes in June 1791, when Louis XVI attempted to escape France and rally foreign support for the restoration of his absolute power.

This act of betrayal eroded any remaining support for the monarchy among the populace and the Assembly, leading to increased calls for the establishment of a republic.

The people’s experiment with a constitutional monarchy thus served to highlight the irreconcilable differences between the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and the traditional monarchical order, setting the stage for the republic’s proclamation.

Birth of a Republic

The proclamation of the First French Republic in September 1792 represented a radical departure from centuries of monarchical rule, embodying the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

This transition was catalyzed by escalating political tensions, military challenges, and the radicalization of the revolution, particularly after the king’s failed flight and perceived betrayal.

The Republic’s birth was a moment of immense optimism and aspiration, as it promised to reshape French society on the principles of democratic governance and civic equality. It also marked the beginning of a new calendar, symbolic of the revolutionaries’ desire to break completely with the past and start anew.

However, the early years of the Republic were marked by significant challenges, including internal divisions, economic struggles, and threats from monarchist powers in Europe.

These pressures necessitated the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror, measures aimed at defending the revolution but which also led to extreme political repression.

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, from September 1793 to July 1794, remains one of the most controversial and bloodiest periods of the French Revolution. Under the auspices of the Committee of Public Safety, led by figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, the French government adopted radical measures to purge the nation of perceived enemies of the revolution.

This period saw the widespread use of the guillotine , with thousands executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activities or mere suspicion of disloyalty. The Terror aimed to consolidate revolutionary gains and protect the nascent Republic from internal and external threats, but its legacy is marred by the extremity of its actions and the climate of fear it engendered.

The end of the Terror came with the Thermidorian Reaction on 27th July 1794 (9th Thermidor Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar), which resulted in the arrest and execution of Robespierre and his closest allies.

This marked a significant turning point, leading to the dismantling of the Committee of Public Safety and the gradual relaxation of emergency measures. The aftermath of the Terror reflected a society grappling with the consequences of its radical actions, seeking stability after years of upheaval but still committed to the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality .

Thermidorians and the Directory

Following the Thermidorian Reaction , the political landscape of France underwent significant changes, leading to the establishment of the Directory in November 1795.

This new government, a five-member executive body, was intended to provide stability and moderate the excesses of the previous radical phase. The Directory period was characterized by a mix of conservative and revolutionary policies, aimed at consolidating the Republic and addressing the economic and social issues that had fueled the revolution.

Despite its efforts to navigate the challenges of governance, the Directory faced significant opposition from royalists on the right and Jacobins on the left, leading to a period of political instability and corruption.

The Directory’s inability to resolve these tensions and its growing unpopularity set the stage for its downfall. The coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, ended the Directory and established the Consulate, marking the end of the revolutionary government and the beginning of Napoleonic rule.

While the Directory failed to achieve lasting stability, it played a crucial role in the transition from radical revolution to the establishment of a more authoritarian regime, highlighting the complexities of revolutionary governance and the challenges of fulfilling the ideals of 1789.

French Revolution End and Outcome: Napoleon’s Rise

The revolution’s end is often marked by Napoleon’s coup d’état on 18 Brumaire , which not only concluded a decade of political instability and social unrest but also ushered in a new era of governance under his rule.

This period, while stabilizing France and bringing much-needed order, seemed to contradict the revolution’s initial aims of establishing a democratic republic grounded in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Napoleon’s rise to power, culminating in his coronation as Emperor, symbolizes a complex conclusion to the revolutionary narrative, intertwining the fulfillment and betrayal of its foundational ideals.

Evaluating the revolution’s success requires a nuanced perspective. On one hand, it dismantled the Ancien Régime, abolished feudalism, and set forth the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, laying the cornerstone for modern democracy and human rights.

These achievements signify profound societal and legal transformations that resonated well beyond France’s borders, influencing subsequent movements for freedom and equality globally.

On the other hand, the revolution’s trajectory through the Reign of Terror and the subsequent rise of a military dictatorship under Napoleon raises questions about the cost of these advances and the ultimate realization of the revolution’s goals.

The French Revolution’s conclusion with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascension to power is emblematic of its complex legacy. This period not only marked the cessation of years of turmoil but also initiated a new chapter in French governance, characterized by stability and reform yet marked by a departure from the revolution’s original democratic aspirations.

The Significance of the French Revolution

The French Revolution holds a place of prominence in the annals of history, celebrated for its profound impact on the course of modern civilization. Its fame stems not only from the dramatic events and transformative ideas it unleashed but also from its enduring influence on political thought, social reform, and the global struggle for justice and equality.

This period of intense upheaval and radical change challenged the very foundations of society, dismantling centuries-old institutions and laying the groundwork for a new era defined by the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

At its core, the French Revolution was a manifestation of human aspiration towards freedom and self-determination, a vivid illustration of the power of collective action to reshape the world. It introduced revolutionary concepts of citizenship and rights that have since become the bedrock of democratic societies.

Moreover, the revolution’s ripple effects were felt worldwide, inspiring a wave of independence movements and revolutions across Europe, Latin America, and beyond. Its legacy is a testament to the idea that people have the power to overthrow oppressive systems and construct a more equitable society.

The revolution’s significance also lies in its contributions to political and social thought. It was a living laboratory for ideas that were radical at the time, such as the separation of church and state, the abolition of feudal privileges, and the establishment of a constitution to govern the rights and duties of the French citizens.

These concepts, debated and implemented with varying degrees of success during the revolution, have become fundamental to modern governance.

Furthermore, the French Revolution is famous for its dramatic and symbolic events, from the storming of the Bastille to the Reign of Terror, which have etched themselves into the collective memory of humanity.

These events highlight the complexities and contradictions of the revolutionary process, underscoring the challenges inherent in profound societal transformation.

Key Figures of the French Revolution

The French Revolutions were painted by the actions and ideologies of several key figures whose contributions defined the era. These individuals, with their diverse roles and perspectives, were central in navigating the revolution’s trajectory, capturing the complexities and contradictions of this tumultuous period.

Maximilien Robespierre , often synonymous with the Reign of Terror, was a figure of paradoxes. A lawyer and politician, his early advocacy for the rights of the common people and opposition to absolute monarchy marked him as a champion of liberty.

However, as a leader of the Committee of Public Safety, his name became associated with the radical phase of the revolution, characterized by extreme measures in the name of safeguarding the republic. His eventual downfall and execution reflect the revolution’s capacity for self-consumption.

Georges Danton , another prominent revolutionary leader, played a crucial role in the early stages of the revolution. Known for his oratory skills and charismatic leadership, Danton was instrumental in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic.

Unlike Robespierre, Danton is often remembered for his pragmatism and efforts to moderate the revolution’s excesses, which ultimately led to his execution during the Reign of Terror, highlighting the volatile nature of revolutionary politics.

Louis XVI, the king at the revolution’s outbreak, represents the Ancient Régime’s complexities and the challenges of monarchical rule in a time of profound societal change.

His inability to effectively manage France’s financial crisis and his hesitancy to embrace substantial reforms contributed to the revolutionary fervor. His execution in 1793 symbolized the revolution’s radical break from monarchical tradition and the birth of the republic.

Marie Antoinette, the queen consort of Louis XVI, became a symbol of the monarchy’s extravagance and disconnect from the common people. Her fate, like that of her husband, underscores the revolution’s rejection of the old order and the desire for a new societal structure based on equality and merit rather than birthright.

Jean-Paul Marat , a journalist and politician, used his publication, L’Ami du Peuple, to advocate for the rights of the lower classes and to call for radical measures against the revolution’s enemies.

His assassination by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, in 1793 became one of the revolution’s most famous episodes, illustrating the deep divisions within revolutionary France.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte, though not a leader during the revolution’s peak, emerged from its aftermath to shape France’s future. A military genius, Napoleon used the opportunities presented by the revolution’s chaos to rise to power, eventually declaring himself Emperor of the French.

His reign would consolidate many of the revolution’s reforms while curtailing its democratic aspirations, embodying the complexities of the revolution’s legacy.

These key figures, among others, played significant roles in the unfolding of the French Revolution. Their contributions, whether for the cause of liberty, the maintenance of order, or the pursuit of personal power, highlight the multifaceted nature of the revolution and its enduring impact on history.

References:

(1) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 119-221.

(2) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 11-12

(3) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp. 56-57.

(4) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 24-25

(5) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 12-14.

(6) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 14-25

(7) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 63-65.

(8) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 242-244.

(9) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 74.

(10) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 82 – 84.

(11) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, p. 20.

(12) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 60-61.

(13) https://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf (14) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 104-105.

(15) French Revolution. “A Citizen Recalls the Taking of the Bastille (1789),” January 11, 2013. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/humbert-taking-of-the-bastille-1789/.

(16) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 74-75.

(17) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 36-37.

(18) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its origins to 1793. Routledge, 1957, pp. 121-122.

(19) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 428-430.

(20) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, p. 80.

(21) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 116-117.

(22) Fitzsimmons, Michael “The Principles of 1789” in McPhee, Peter, editor. A Companion to the French Revolution. Blackwell, 2013, pp. 75-88.

(23) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 68-81.

(24) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 45-46.

(25) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989,.pp. 460-466.

(26) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 524-525.

(27) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 47-48.

(28) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 51.

(29) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 128.

(30) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 30 -31.

(31) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp.. 53 -62.

(32) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 129-130.

(33) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 62-63.

(34) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 156-157, 171-173.

(35) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 65-66.

(36) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 543-544.

(37) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 179-180.

(38) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 184-185.

(39) Hampson, Norman. Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge, 1963, pp. 148-149.

(40) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 191-192.

(41) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Routledge, 1962, pp. 252-254.

(42) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 88-89.

(43) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1990, pp. 576-79.

(44) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 649-51

(45) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 242-243.

(46) Connor, Clifford. Marat: The Tribune of the French Revolution. Pluto Press, 2012.

(47) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 722-724.

(48) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 246-47.

(49) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 209-210.

(50) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp 68-70.

(51) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 205-206

(52) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, 784-86.

(53) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 262.

(54) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 619-22.

(55) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 269-70.

(56) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 276.

(57) Robespierre on Virtue and Terror (1794). https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/robespierre-virtue-terror-1794/. Accessed 19 May 2020.

(58) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 290-91.

(59) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 293-95.

(60) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 49-51.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/the-french-revolution/ ">French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World History Project - Origins to the Present

Course: world history project - origins to the present > unit 6.

- READ: Sovereignty

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: The Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment

- WATCH: The Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment

- READ: Ingredients for Revolution

- READ: The Enlightenment

- READ: The Atlantic Revolutions

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: The Haitian Revolution

- WATCH: The Haitian Revolution

- READ: West Africa in the Age of Revolutions

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Colonization and Resistance - Through a Pueblo Lens

- WATCH: Colonization and Resistance: Through a Pueblo Lens | World History Project

READ: Origins and Impacts of Nationalism

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Nationalism

- WATCH: Nationalism

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Samurai, Daimyo, Matthew Perry, and Nationalism

- WATCH: Samurai, Daimyo, Matthew Perry, and Nationalism

- Liberal and National Revolutions

First read: preview and skimming for gist

Second read: key ideas and understanding content.

- What is a nation? Are nations natural or biological?

- Why does the author describe nations as an “imagined communities”?

- How did French military victories contribute to the rise of nationalism in France and elsewhere?

- In what context did nationalism take hold in Europe? In the Americas?

- What factors helped nationalism take hold in Germany and Italy?

Third read: evaluating and corroborating

- What is the author’s main argument about nationalism? Do you find it convincing? Why or why not?

- What are some of the ways in which nationalism helped liberate people or bring about positive political change in this era? Can you predict any potential problems or challenges that nationalism might also bring? If so, what are they?

Origins and Impacts of Nationalism

What exactly is nationalism, other reasons…, conclusions and future differences, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Napoleon Bonaparte During the Early French Revolution (1789-1794)

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

Of all the careers that soared to meteoric heights during the chaotic decade of the French Revolution (1789-1799), none was more spectacular nor impactful than that of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821). From an unremarkable birth into minor Corsican nobility, Napoleon would find in the Revolution a path to fame, military success, and ultimately, to his role as Emperor of the French.

A quick glance at his career would be enough to show how intertwined his fate would become with the Revolution. His promising performance at the Siege of Toulon in 1793 would lead to his brilliant command of the Army of Italy , which in turn would help provide him with enough popularity and influence to seize control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire , the event which many scholars consider to be the end of the Revolution. To understand this version of Napoleon, it is necessary to look at the person he was at the start of the Revolution; hardly the picture of a dashing military commander or French patriot, the Napoleon of 1789 was a thin, awkward man who did not yet even consider himself French.

Indeed, in 1789, 20-year-old Napoleon was in something of an identity crisis, looking to reconcile his ambitions of literary fame with his education as a soldier, his devotion to French revolutionary ideals with his Corsican nationalism. The early Revolution was undoubtedly a time of personal development for the young artillery lieutenant, the outcome of which would not only affect his own future but also the fate of all of Europe .

The Corsican

In 1768, the year before Napoleon's birth, the Kingdom of France purchased Corsica from the Republic of Genoa, which had distantly ruled it for the previous few centuries. Although nominally under Genoese control, the Corsicans had been used to effectively ruling themselves. They had recently claimed independence, declaring the Corsican Republic in 1755, but such aspirations to self-rule would come to an end with the arrival of the French. In Napoleon's own words, he was born "as the fatherland was dying. Thirty thousand Frenchmen, vomited upon our coasts, drowning the seat of liberty in torrents of blood" (Bell, 18).

There was resistance, of course. Led by Pasquale Paoli (1725-1807), the Corsicans were initially successful at beating back the French Expeditionary Force that landed on their shores in 1768. However, this success would not last, as the French had the advantage in manpower and supplies; the French victory at the Battle of Ponte Novu in 1769 destroyed the Corsican will to fight. Although sporadic guerilla warfare continued, Paoli fled to Britain , and Corsica was annexed by France.

Although this defeat was lamented by many Corsicans, some were able to take advantage of this regime change. Napoleon's father, Carlo Buonaparte, was one of them. A former ally of Paoli, Carlo chose to abandon the patriotic cause to ensure a future for his family. His gamble paid off, as Carlo's devotion to the new government allowed him to secure minor nobility status for his family under French law , which in turn allowed him to send his oldest sons to receive education in French royal academies. Because of his father's change in loyalties, ten-year-old Napoleon was educated at the military academy of Brienne in northern France, where he learned French and excelled in mathematics. Paoli, however, would not forget nor forgive Carlo's apparent betrayal.

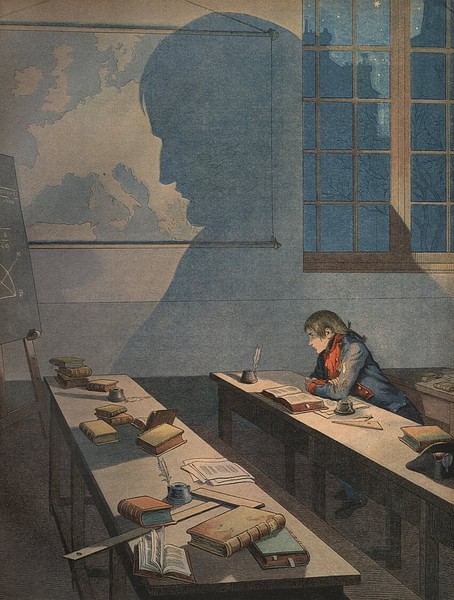

Despite reaping the benefits of French occupation, teenaged Napoleon remained a staunch Corsican nationalist. He idolized the exiled Paoli as a freedom fighter and clung to dreams of an independent Corsica. Such a demeanor, along with his strange accent and difficult-to-pronounce name (recorded in the school registry as Neapoleonne Buonaparte), quickly alienated Napoleon from his French classmates. Much of his time was spent alone, and he would soon develop a “thoughtful and gloomy” nature, according to his headmaster (Roberts, 11). Lacking companions, Napoleon would find company amongst his books. He adored poetry and history, although he also took an interest in the Enlightenment philosophers, who were so popular at the time. He became especially fond of Jean-Jacques Rousseau , perhaps because of Rousseau's own support of the Corsican plight. Napoleon adopted many of Rousseau's ideas, which would soon become the same ideas that fueled the Revolution.

In 1786, the year after he graduated from the prestigious Ecole Militaire as an artillery lieutenant, 16-year-old Napoleon embarked on something of a literary career. An exceptionally ambitious young man, it did not seem likely that he, as a Corsican-born man of minor nobility, would amount to much in the French army. To compensate, Napoleon sought literary glory instead. Over the next ten years, he would write over 60 essays, novellas, and letters. His first known essay, written on 26 April 1786, argued that Corsica had an undeniable right to resist the French, while a follow-up essay entitled On Suicide was an interesting mixture of nationalistic pride and teenaged angst:

My fellow countrymen are weighed down with chains, while they kiss with fear the hand that oppresses them…you Frenchmen, not content with having robbed us of everything we hold dear, have also corrupted our character. A good patriot ought to die when his fatherland has ceased to exist. (Roberts, 22)

Although borderline treasonous, especially for an enlisted officer in the French army, Napoleon continued espousing his nationalism in his writings over the next few years. He spent months, on and off, writing a comprehensive history of Corsica, in which he compared his countrymen to the virtuous ancient Romans, while also penning a novella entitled New Corsica , which was, in the words of biographer Andrew Roberts, little better than a graphic "Francophobic revenge fantasy" (Roberts, 31). He would find little publication luck, and for a time, it appeared the young artillery lieutenant may be doomed to literary as well as military obscurity.

Then, in 1789, the course of history shifted. The Estates-General of 1789 declared themselves a National Assembly, wresting authority from the king. In July, the commoners took matters into their own hands with the Storming of the Bastille . The French Revolution had begun.

The Revolutionary

Despite his obligations as a French officer, Napoleon welcomed the Revolution, viewing it as a manifestation of the Enlightenment ideals he had come to believe in, a triumph of logic and reason. Still, he did his soldierly duty and helped disperse a riot in Auxonne eight days after the Bastille fell, arresting 33 people. In August, he received permission to return to Corsica on sick leave. Back in the Corsican capital of Ajaccio, Napoleon was reunited with his brothers, Joseph and Lucien, the latter of whom was already a staunch supporter of radical revolutionary politics at the age of 14. The Bonapartes became outspoken revolutionary supporters in Ajaccio, sporting the tricolor cockade in their hats and signing their letters with the obligatory "citizen".

In early 1790, the Bonapartes would be endeared even closer to the revolutionary cause when the National Assembly proclaimed Corsica to officially be a department of France. Subject to French laws, Corsicans would now reap the benefits of citizenship, and to make matters even better, the Assembly declared that Corsica would henceforth be governed solely by Corsicans. At the same time, they invited Paoli to return from his 22-year exile. Napoleon was ecstatic, as evidenced by the huge banner that hung from Casa Bonaparte, which read " Vive la Nation! Vive Paoli! " (Roberts, 33).

Not every Corsican was thrilled with these developments, however, with no one less happy than Napoleon's hero Pasquale Paoli himself. The aged freedom fighter saw in the Assembly's decree nothing but an attempt by Paris to further impose its will on the island. He saw in the Bonaparte brothers nothing but the children of a French collaborator. Carlo Buonaparte may have been dead, but by the way his children were celebrating the Paris government, Paoli considered them no better. He refused to support Joseph Bonaparte's campaign for deputy to the Corsican assembly, and he was further offended by a pamphlet written by Napoleon, which derided many of the returned Corsican exiles for their preference for a constitution in the style of Great Britain rather than for the constitution currently being developed by the Assembly. Because of this pamphlet, Paoli passive-aggressively refused Napoleon's request to write the dedication for his history of Corsica and even refused to read the manuscript, using the excuse that "history should not be written in youth" (Roberts, 34). Napoleon's dreams of literary success were again frustrated, this time by his childhood hero.

After briefly returning to duty in France, Napoleon came back to Corsica in early 1792 to stand for election as a lieutenant colonel in the Corsican National Guard. It was a dirty and dramatic election, filled with bribes and even the temporary kidnappings of election officials. Paoli supported Napoleon's opponent, but Napoleon had the support of Antoine-Christoph Saliceti, who represented the National Convention on Corsica (the Convention having succeeded the National Assembly as France's governing body). With the support of Paris, Napoleon won the election and the lieutenant colonelcy.

Not long after Napoleon won his post, Saliceti gave the order for all monasteries and convents in Ajaccio to be stripped, the proceeds to be shipped to fund the treasury of the central government in Paris. This was met with outrage by the Catholic citizens of Ajaccio, who rioted on Easter Sunday 1792. It fell to Napoleon to suppress the revolt. The bloody struggle would last four days, in which one of Napoleon's lieutenants was even shot dead at his side. During the confusion, Napoleon apparently tried unsuccessfully to capture the town's fortified citadel, which was garrisoned by French regular troops. Paoli, seeing an opportunity to rid himself of the troublesome colonel, wrote to the war ministry in Paris, accusing Napoleon of treason. Fortunately for Napoleon, nothing ever came of the matter, as the war ministry had other things to worry about; on 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria and Prussia and invaded the Austrian Netherlands.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The Jacobin

Napoleon could not stay in Ajaccio following the Easter Sunday debacle, so he returned to Paris, hoping to resume his commission in the army. He was in the city during the Demonstration of 20 June 1792 , when a Parisian mob stormed the Tuileries Palace , accosted King Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette , and forced the king to wear the red cap of liberty atop the palace balcony. Although he had no respect for the monarchy, Napoleon hated mobs and wondered why the king and his guards had allowed the mob to humiliate them without a fight. According to his friend Bourrienne, Napoleon apparently remarked, "What madness! How could they allow that rabble to enter? Why do they not sweep away four or five hundred of them with cannon? The rest would take themselves off very quickly" (Roberts, 39).

He was still in Paris that September when more than 1,200 people were murdered in the city's prisons in the September Massacres . These massacres, a reaction to Prussia's and Austria's threat to destroy Paris, were defended by Napoleon, who stated, "I think the massacres…have produced a powerful effect on the men of the invading army. In one moment, they saw a whole population rise up against them" (Roberts, 40). These words found him inching closer to Jacobinism, an ideology already fully embraced by his brother Lucien, who went by the alias "Brutus" in the Corsican chapter of the Jacobin Club.

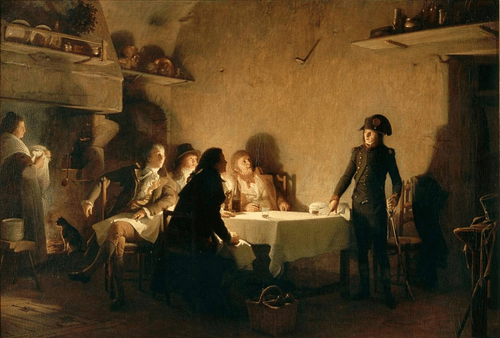

In 1793, he wrote a pamphlet entitled Le Souper de Beaucaire , an account of a fictional dinner in the village of Beaucaire. Taking the form of a discussion between himself and a group of disgruntled merchants, the pamphlet argues that France was in existential danger and that the Jacobin government had to be supported, lest vengeful aristocrats engulf the nation. The pamphlet, which marked Napoleon as a true sympathizer of the Jacobin cause, caught the attention of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the more famous Jacobin leader, who arranged for its publication. This was a turning point in Napoleon's career, giving him valuable connections.

He returned to Corsica in late 1792, just after the declaration of the First French Republic, to champion the Jacobins' cause. His return found the island even more anti-French than when he had left it, as many had become alienated by the Revolution's policies of dechristianization and by the September Massacres. Napoleon, meanwhile, was fully on the side of the Revolution. As biographer Roberts explains:

He moved from being a Corsican nationalist to a French revolutionary not because he finally got over being bullied at school, or because of anything to do with his father…but simply because the politics of France and Corsica had profoundly changed and so too had his place within them. (41)

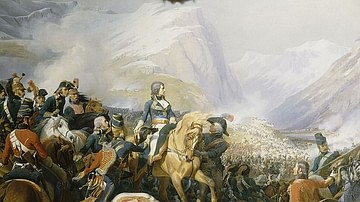

Around this time, he gave up writing history and fiction, stating that he no longer had "the small ambition to become an author" (Bell, 19). The Revolution had given him a new purpose. In February 1793, a month after the execution of King Louis XVI , Napoleon was given his first true military command. His task was to liberate three small Sardinian islands from the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, which had recently joined the quickly expanding list of France's enemies. He had been selected by Paoli, who was perhaps secretly hoping he would fail – far from the 10,000 men the Paris Convention requested for the expedition, Paoli had furnished Napoleon with only 1,800. This was not nearly enough to complete the task, and Napoleon was forced to return to Corsica in defeat.

By now, the break between Paoli's supporters and the Convention was inevitable; indeed, Paoli's loyalties were drifting closer to Great Britain, his old hosts during his exile. Yet, even now Napoleon tried to reconcile his loyalty to his homeland with his newfound identity as a French revolutionary. But when Saliceti ordered Paoli's arrest for treason, his supporters rose in revolt against the Jacobin regime. Napoleon realized a decision had to be made. He chose the Republic.

The Soldier

On 3 May 1793, Napoleon was detained by Paolist supporters on his way to join his brother Joseph in Bastia. He was freed soon after by villagers sympathetic to France, although the family estate, Casa Bonaparte, was ransacked by Paolists a few weeks later. Having seized the city of Ajaccio, Paoli's government officially outlawed the Bonaparte family. A despondent Napoleon finally denounced his childhood hero, writing that Paoli had "hatred and vengeance in his heart" (Roberts, 44). With few options, the entire Bonaparte family left Corsica on 11 July 1793 aboard the ship Proselyte , landing at the French port city of Toulon two days later. By the end of the month, Paoli recognized King George III of Great Britain as the ruler of Corsica. Save for a brief pitstop on the island in 1799 on his return voyage from campaigning in Egypt , Napoleon would never see Corsica again.

It would not take long for Napoleon's Jacobin connections to pay off. On 24 August, a combined Coalition army of British, Spanish, and Neapolitans occupied Toulon at the invitation of the fédéré rebels who had revolted there. Due to his friendship with major Jacobin figures such as Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, and because the army had been depleted by mass emigrations and executions, Napoleon was immediately given the rank of major in the army that was sent to retake the city. By October, he was in command of all the artillery involved in the siege. His brilliant and daring actions during the Siege of Toulon became the first chapter of the Napoleonic legend; he played a huge role in the city's fall in December. For his actions, he received the rank of brigadier-general on 22 December, at the age of just 24.

Using his newfound influence, Napoleon submitted a plan for the invasion of Italy to the Committee of Public Safety in early 1794. It was supported by Augustin Robespierre, who was overseeing the Italian theater of war, and who had helped get Napoleon appointed as the artillery commander of the Army of Italy. That July, Napoleon embarked on secret missions to Genoa on Robespierre's behalf, in the hopes of becoming closer integrated into the Jacobin leadership. It was the worst possible time he could have done this. That month, the Thermidorian Reaction led to the downfall and execution of top Jacobin leaders, including the Robespierre brothers. Due to his relationship with Augustin, Napoleon was arrested on 9 August in Nice.

Had Napoleon been in Paris when the Jacobins lost power, he very well could have been guillotined along with his former patron. Instead, he was released on lack of evidence on 20 August. While other former Jacobins may have wished to slide into obscurity following such a close call, Napoleon was still a man of insatiable ambition. His exploits soon caught the eye of one of the new Thermidorian leaders, Paul Barras, who tasked Napoleon with putting down an uprising in Paris. Napoleon executed this task, the revolt of 13 Vendemiaire , with calculated efficiency, the famous "whiff of grapeshot", elevating his position further. In March 1796, partly thanks to the efforts of his new patron Barras, Napoleon was given command of the Army of Italy. Napoleon's First Italian Campaign would be the decisive moment in the War of the First Coalition , and would also set Napoleon on his trajectory toward the throne.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Bell, David A. Napoleon. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Bell, David A. The First Total War. Mariner Books, 2014.

- Carlyle, Thomas & Sorensen, David R. & Kinser, Brent E. & Engel, Mark. The French Revolution . Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Francois Furet & Mona Ozouf & Arthur Goldhammer. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander. The Napoleonic Wars. Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Palmer, R. R. Twelve who ruled. Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon. Penguin Books, 2015.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Napoleon's Italian Campaign