Poetry Explained

How to Write a Poetry Essay (Complete Guide)

Unlock success in poetry essays with our comprehensive guide. Uncover the process to help aid understanding of how best to create a poetry essay.

While many of us read poetry for pleasure, it is undeniable that many poetry readers do so in the knowledge that they will be assessed on the text they are reading, either in an exam, for homework, or for a piece of coursework. This is clearly a daunting task for many, and lots of students don’t even know where to begin. We’re here to help! This guide will take you through all the necessary steps so that you can plan and write great poetry essays every time. If you’re still getting to grips with the different techniques, terms, or some other aspect of poetry, then check out our other available resources at the bottom of this page.

This Guide was Created by Joe Samantaria

Degree in English and Related Literature, and a Masters in Irish Literature

Upon completion of his degrees, Joe is an English tutor and counts W.B. Yeats , Emily Brontë , and Federico Garcia Lorca among his favorite poets. He has helped tutor hundreds of students with poetry and aims to do the same for readers and Poetry + users on Poem Analysis.

How to Write a Poetry Essay

- 1 Before You Start…

- 2 Introductions

- 3 Main Paragraphs

- 4 Conclusions

- 6 Other Resources

Before You Start…

Before we begin, we must address the fact that all poetry essays are different from one another on account of different academic levels, whether or not the essay pertains to one poem or multiple, and the intended length of the essay. That is before we even contend with the countless variations and distinctions between individual poems. Thus, it is impossible to produce a single, one-size-fits-all template for writing great essays on poetry because the criteria for such an essay are not universal. This guide is, therefore, designed to help you go about writing a simple essay on a single poem, which comes to roughly 1000-1200 words in length. We have designed it this way to mirror the requirements of as many students around the world as possible. It is our intention to write another guide on how to write a comparative poetry essay at a later date. Finally, we would like to stress the fact that this guide is exactly that: a guide. It is not a set of restrictive rules but rather a means of helping you get to grips with writing poetry essays. Think of it more like a recipe that, once practiced a few times, can be modified and adapted as you see fit.

The first and most obvious starting point is the poem itself and there are some important things to do at this stage before you even begin contemplating writing your essay. Naturally, these things will depend on the nature of the essay you are required to write.

- Is the poem one you are familiar with?

- Do you know anything about the context of the poem or the poet?

- How much time do you have to complete the essay?

- Do you have access to books or the internet?

These questions matter because they will determine the type, length, and scope of the essay you write. Naturally, an essay written under timed conditions about an unfamiliar poem will look very different from one written about a poem known to you. Likewise, teachers and examiners will expect different things from these essays and will mark them accordingly.

As this article pertains to writing a poverty essay, we’re going to assume you have a grasp of the basics of understanding the poems themselves. There is a plethora of materials available that can help you analyze poetry if you need to, and thousands of analyzed poems are available right here. For the sake of clarity, we advise you to use these tools to help you get to grips with the poem you intend to write about before you ever sit down to actually produce an essay. As we have said, the amount of time spent pondering the poem will depend on the context of the essay. If you are writing a coursework-style question over many weeks, then you should spend hours analyzing the poem and reading extensively about its context. If, however, you are writing an essay in an exam on a poem you have never seen before, you should perhaps take 10-15% of the allotted time analyzing the poem before you start writing.

The Question

Once you have spent enough time analyzing the poem and identifying its key features and themes, you can turn your attention to the question. It is highly unlikely that you will simply be asked to “analyze this poem.” That would be too simple on the one hand and far too broad on the other.

More likely, you will be asked to analyze a particular aspect of the poem, usually pertaining to its message, themes, or meaning. There are numerous ways examiners can express these questions, so we have outlined some common types of questions below.

- Explore the poet’s presentation of…

- How does the poet present…

- Explore the ways the writer portrays their thoughts about…

These are all similar ways of achieving the same result. In each case, the examiner requires that you analyze the devices used by the poet and attempt to tie the effect those devices have to the poet’s broader intentions or meaning.

Some students prefer reading the question before they read the poem, so they can better focus their analytical eye on devices and features that directly relate to the question they are being asked. This approach has its merits, especially for poems that you have not previously seen. However, be wary of focusing too much on a single element of a poem, particularly if it is one you may be asked to write about again in a later exam. It is no good knowing only how a poem links to the theme of revenge if you will later be asked to explore its presentation of time.

Essay plans can help focus students’ attention when they’re under pressure and give them a degree of confidence while they’re writing. In basic terms, a plan needs the following elements:

- An overarching answer to the question (this will form the basis of your introduction)

- A series of specific, identifiable poetic devices ( metaphors , caesura , juxtaposition , etc) you have found in the poem

- Ideas about how these devices link to the poem’s messages or themes.

- Some pieces of relevant context (depending on whether you need it for your type of question)

In terms of layout, we do not want to be too prescriptive. Some students prefer to bullet-point their ideas, and others like to separate them by paragraph. If you use the latter approach, you should aim for:

- 1 Introduction

- 4-5 Main paragraphs

- 1 Conclusion

Finally, the length and detail of your plan should be dictated by the nature of the essay you are doing. If you are under exam conditions, you should not spend too much time writing a plan, as you will need that time for the essay itself. Conversely, if you are not under time pressure, you should take your time to really build out your plan and fill in the details.

Introductions

If you have followed all the steps to this point, you should be ready to start writing your essay. All good essays begin with an introduction, so that is where we shall start.

When it comes to introductions, the clue is in the name: this is the place for you to introduce your ideas and answer the question in broad terms. This means that you don’t need to go into too much detail, as you’ll be doing that in the main body of the essay. That means you don’t need quotes, and you’re unlikely to need to quote anything from the poem yet. One thing to remember is that you should mention both the poet’s name and the poem’s title in your introduction. This might seem unnecessary, but it is a good habit to get into, especially if you are writing an essay in which other questions/poems are available to choose from.

As we mentioned earlier, you are unlikely to get a question that simply asks you to analyze a poem in its entirety, with no specific angle. More likely, you’ll be asked to write an essay about a particular thematic element of the poem. Your introduction should reflect this. However, many students fall into the trap of simply regurgitating the question without offering anything more. For example, a question might ask you to explore a poet’s presentation of love, memory, loss, or conflict . You should avoid the temptation to simply hand these terms back in your introduction without expanding upon them. You will get a chance to see this in action below.

Let’s say we were given the following question:

Explore Patrick Kavanagh’s presentation of loss and memory in Memory of My Father

Taking on board the earlier advice, you should hopefully produce an introduction similar to the one written below.

Patrick Kavanagh presents loss as an inescapable fact of existence and subverts the readers’ expectations of memory by implying that memories can cause immense pain, even if they feature loved ones. This essay will argue that Memory of My Father depicts loss to be cyclical and thus emphasizes the difficulties that inevitably occur in the early stages of grief.

As you can see, the introduction is fairly condensed and does not attempt to analyze any specific poetic elements. There will be plenty of time for that as the essay progresses. Similarly, the introduction does not simply repeat the words ‘loss’ and ‘memory’ from the question but expands upon them and offers a glimpse of the kind of interpretation that will follow without providing too much unnecessary detail at this early stage.

Main Paragraphs

Now, we come to the main body of the essay, the quality of which will ultimately determine the strength of our essay. This section should comprise of 4-5 paragraphs, and each of these should analyze an aspect of the poem and then link the effect that aspect creates to the poem’s themes or message. They can also draw upon context when relevant if that is a required component of your particular essay.

There are a few things to consider when writing analytical paragraphs and many different templates for doing so, some of which are listed below.

- PEE (Point-Evidence-Explain)

- PEA (Point-Evidence-Analysis)

- PETAL (Point-Evidence-Technique-Analysis-Link)

- IQA (Identify-Quote-Analyze)

- PEEL (Point-Evidence-Explain-Link)

Some of these may be familiar to you, and they all have their merits. As you can see, there are all effective variations of the same thing. Some might use different terms or change the order, but it is possible to write great paragraphs using all of them.

One of the most important aspects of writing these kind of paragraphs is selecting the features you will be identifying and analyzing. A full list of poetic features with explanations can be found here. If you have done your plan correctly, you should have already identified a series of poetic devices and begun to think about how they link to the poem’s themes.

It is important to remember that, when analyzing poetry, everything is fair game! You can analyze the language, structure, shape, and punctuation of the poem. Try not to rely too heavily on any single type of paragraph. For instance, if you have written three paragraphs about linguistic features ( similes , hyperbole , alliteration , etc), then try to write your next one about a structural device ( rhyme scheme , enjambment , meter , etc).

Regardless of what structure you are using, you should remember that multiple interpretations are not only acceptable but actively encouraged. Techniques can create effects that link to the poem’s message or themes in both complementary and entirely contrasting ways. All these possibilities should find their way into your essay. You are not writing a legal argument that must be utterly watertight – you are interpreting a subjective piece of art.

It is important to provide evidence for your points in the form of either a direct quotation or, when appropriate, a reference to specific lines or stanzas . For instance, if you are analyzing a strict rhyme scheme, you do not need to quote every rhyming word. Instead, you can simply name the rhyme scheme as, for example, AABB , and then specify whether or not this rhyme scheme is applied consistently throughout the poem or not. When you are quoting a section from the poem, you should endeavor to embed your quotation within your line so that your paragraph flows and can be read without cause for confusion.

When it comes to context, remember to check whether or not your essay question requires it before you begin writing. If you do need to use it, you must remember that it is used to elevate your analysis of the poem, not replace it. Think of context like condiments or spices. When used appropriately, they can enhance the experience of eating a meal, but you would have every right to complain if a restaurant served you a bowl of ketchup in lieu of an actual meal. Moreover, you should remember to only use the contextual information that helps your interpretation rather than simply writing down facts to prove you have memorized them. Examiners will not be impressed that you know the date a particular poet was born or died unless that information relates to the poem itself.

For the sake of ease, let’s return to our earlier question:

Have a look at the example paragraph below, taking note of the ways in which it interprets the linguistic technique in several different ways.

Kavanagh uses a metaphor when describing how the narrator ’s father had “fallen in love with death” in order to capture the narrator’s conflicted attitudes towards his loss. By conflating the ordinarily juxtaposed states of love and death, Kavanagh implies the narrator’s loss has shattered his previously held understanding of the world and left him confused. Similarly, the metaphor could suggest the narrator feels a degree of jealousy, possibly even self-loathing, because their father embraced death willingly rather than remaining with the living. Ultimately, the metaphor’s innate impossibility speaks to the narrator’s desire to rationalize their loss because the reality, that his father simply died, is too painful for him to bear.

As you can see, the paragraph clearly engages with a poetic device and uses an appropriately embedded quotation. The subsequent interpretations are then varied enough to avoid repeating each other, but all clearly link to the theme of loss that was mentioned in the question. Obviously, this is only one analytical paragraph, but a completed essay should contain 4-5. This would allow the writer to analyze enough different devices and link them to both themes mentioned in the question.

Conclusions

By this stage, you should have written the bulk of your essay in the form of your introduction and 4-5 main analytical paragraphs. If you have done those things properly, then the conclusion should largely take care of itself.

The world’s simplest essay plan sounds something like this:

- Tell them what you’re going to tell them

- Tell them what you’ve told them

This is, naturally, an oversimplification, but it is worth bearing in mind. The conclusion to an essay is not the place to introduce your final, groundbreaking interpretation. Nor is it the place to reveal a hitherto unknown piece of contextual information that shatters any prior critical consensus with regard to the poem you are writing about. If you do either of these things, the examiner will be asking themselves one simple question: why didn’t they write this earlier?

In its most simple form, a conclusion is there, to sum up the points you have made and nothing more.

As with the previous sections, there is a little more to a great conclusion than merely stating the things you have already made. The trick to a great conclusion is to bind those points together to emphasize the essay’s overarching thread or central argument. This is a subtle skill, but mastering it will really help you to finish your essays with a flourish by making your points feel like they are more than the sum of their parts.

Finally, let’s remind ourselves of the hypothetical essay question we’ve been using:

Remember that, just like your introduction, your conclusion should be brief and direct and must not attempt to do more than it needs to.

In conclusion, Kavanagh’s poem utilizes numerous techniques to capture the ways in which loss is both inescapable and a source of enormous pain. Moreover, the poet subverts positive memories by showcasing how they can cause loved ones more pain than comfort in the early stages of grief. Ultimately, the poem demonstrates how malleable memory can be in the face of immense loss due to the way the latter shapes and informs the former.

As you can see, this conclusion is confident and authoritative but does not need to provide evidence to justify this tone because that evidence has already been provided earlier in the essay. You should pay close attention to the manner in which the conclusion links different points together under one banner in order to provide a sense of assuredness.

You should refer to the poet by either using their full name or, more commonly, their surname. After your first usage, you may refer to them as ‘the poet.’ Never refer to the poet using just their first name.

This is a good question, and the answer entirely depends on the level of study as well as the nature of the examination. If you are writing a timed essay for a school exam, you are unlikely to need any form of referencing. If, however, you are writing an essay as part of coursework or at a higher education institution, you may need to refer to the specific guidelines of that institution.

Again, this will depend on the type of essay you are being asked to write. If you are writing a longer essay or writing at a higher educational level, it can be useful to refer to other poems in the writer’s repertoire to help make comments on an aspect of the poem you are primarily writing about. However, for the kind of essay outlined in this article, you should focus solely on the poem you have been asked to write about.

This is one of the most common concerns students have about writing essays . Ultimately, the quality of an essay is more likely to be determined by the quality of paragraphs than the quantity anyway, so you should focus on making your paragraphs as good as they can be. Beyond this, it is important to remember that the time required to write a paragraph is not fixed. The more you write, the faster they will become. You should trust the process, focus on making each paragraph as good as it can be, and you’ll be amazed at how the timing issue takes care of itself.

Other Resources

We hope you have found this article useful and would love for you to comment or reach out to us if you have any queries about what we’ve written. We’d love to hear your feedback!

In the meantime, we’ve collated a list of resources you might find helpful when setting out to tackle a poetry essay, which you can find below.

- Do poems have to rhyme?

- 10 important elements of poetry

- How to analyze a poem with SMILE

- How to approach unseen poetry

- 18 Different Types of Themes in Poetry

Home » Poetry Explained » How to Write a Poetry Essay (Complete Guide)

About Joe Santamaria

Experts in poetry.

Our work is created by a team of talented poetry experts, to provide an in-depth look into poetry, like no other.

Cite This Page

Santamaria, Joe. "How to Write a Poetry Essay (Complete Guide)". Poem Analysis , https://poemanalysis.com/how-to-write-a-poetry-essay/ . Accessed 8 August 2024.

Help Center

Request an Analysis

(not a member? Join now)

Poem PDF Guides

PDF Learning Library

Beyond the Verse Podcast

Poetry Archives

Poet Biographies

Useful Links

Poem Explorer

Poem Generator

Poem Solutions Limited, International House, 36-38 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NG, United Kingdom

Discover and learn about the greatest poetry, straight to your inbox

Unlock the Secrets to Poetry

Writing a poetry book requires courage, stamina, and a lot of patience with yourself. The poetry book ranks at the top of many poets’ to-do lists, but getting a manuscript in front of poetry book publishers takes years of writing and planning.

This article covers the essentials of getting new poetry books into print, covering both the writing and publishing process for contemporary poets. Let’s get into it: How do you write a poetry book?

How to Write a Poetry Book: Contents

How Many Poems in a Poetry Book?

What is a poetry chapbook, should i publish a chapbook or a full-length poetry collection, do modern poetry books follow a theme, how do you order the poems when writing a poetry book, how should i format my poetry manuscript, i’ve finished writing a poetry book. how do i publish it, what do poetry book publishers look for in manuscripts, checklist: how to publish a poetry book, who are some poetry book publishers i can submit to, do i need an agent to publish my poetry book, what can you tell me about self-publishing a poetry book, a final note on how to publish a poetry book: be patient.

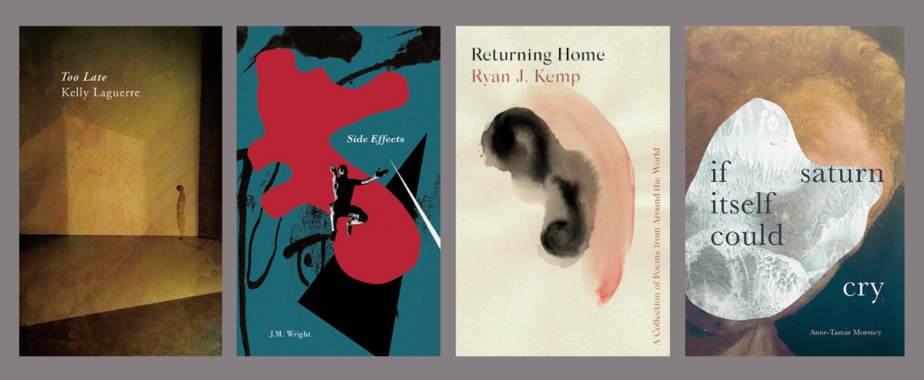

Most poetry book publishers abide by the following definition: a poetry book is any collection of poems longer than 48 pages. There’s no standard for how many poems go into a collection; it’s much more important that the collection feels “finished” to the poet.

Poetry book publishers often define a poetry book as any collection of poems longer than 48 pages.

With that said, feel free to experiment with length and content while writing a poetry book. You could, theoretically, publish a book of 3 16-page poems, or something similarly eccentric!

A poetry chapbook—in contrast to modern poetry books—is a collection of poems under 48 pages in length. Because of this page restraint, poetry chapbooks are often thematic and dwell upon a small group of topics; they are rarely narrative in nature. Everything we discuss about how to write a poetry book applies to chapbooks as well.

A poetry chapbook—in contrast to modern poetry books—is a collection of poems under 48 pages in length.

Often, a poet will publish a chapbook before they publish a full length collection (though they don’t have to). In the publishing world, a chapbook serves as a “sample” of a poet’s potential. If the chapbook is well-received, then that poet is more likely to publish a full-length collection in the future. The poet might also publish poems in the full-length collection that were first featured in their chapbook.

Often, a poet will publish a chapbook before they publish a full length collection.

Instead of writing a poetry book, most modern poets begin their publishing journey with a chapbook. Melissa Lozada-Oliva and Olivia Gatwood both published chapbooks through Button Poetry, which gave both poets an opportunity to tour and sell those books across the U.S. As a result, Gatwood has a new full-length collection , and MLO published a novel in verse .

In other words, how do you approach crafting a poetry manuscript? This is probably the trickiest part about assembling a collection of poetry. Like much of creative writing, there’s no formula for how to write a poetry book.

Many new poetry books do follow a theme . Collections about love, death, grief, and oppression certainly populate the poetry shelves of bookstores. However, a theme is only one way of connecting poems together. A poetry collection doesn’t need to be about something; the poems just need some sort of connecting thread.

A poetry collection doesn’t need to be about something; the poems just need some sort of connecting thread.

For example, a collection can be centered around poetry form . Every poem in Terrance Hayes’ collection American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin is, as you can guess, an American Sonnet. Hayes’ poems range from the political to the romantic, but all of them are united in form and in motive.

Poetry can also tell a story. Anne Carson’s lyrical poems in Autobiography of Red tell the story of Geryon, a monster of Greek myth re-imagined as the protagonist of a queer Bildungsroman. Carson’s poems are haunting, lucid, and wonderfully absurd, pushing the boundaries of what a poetry collection can accomplish. Ilya Kaminsky does something similar in Deaf Republic , a poetry collection about a fictional town under occupation. Kaminsky’s collection is at once a celebration of humankind’s resilience and a stark warning against totalitarianism, with each poem stacked off each other like cards in a deck.

Likewise, Danez Smith’s collection Don’t Call Us Dead centers around the theme of kaleidoscopic identities, and the collection begins in story. The first third of the book consists of poems searching for a “Heaven for black boys”—a space of respite, a land “that loves [its people] back.” After this first section, the rest of the poems examine Smith’s other identities, uncovering the experience of being black, HIV-positive, and genderqueer.

And, yes, many modern poetry books do follow a theme. The poems of a collection are often united by topic. Louise Gluck’s collection Wild Iris dwells on nature, existence, and the cycle of life; Richard Siken’s collection Crush tells heartfelt stories about queer desire and loss. Recently, I read sam sax’s new collection Pig , a collection of poems that are thematically, metaphorically, or quite literally concerned with pigs. (It’s phenomenal.)

Many poets center their collections on identity and personal experience, and through a combination of wit, authenticity, and the building blocks of poetry , your collection will certainly achieve the same.

Most new poetry books don’t follow a linear narrative structure, so ordering the poems in a collection can prove challenging.

When thinking about the composition of a poetry book, remember the Five E’s:

- Enmeshment: Do the poems feel related to each other? Can you explain why one poem follows or precedes another?

- Evenness: Do the poems feel evenly spread out? Or does one part of the manuscript feel “better written” than another part?

- Evolution: Does the subject matter change and grow overtime? Does the speaker come to new revelations? Or do ideas merely repeat themselves in parallel ways?

- Experience: Do these poems offer new experiences for the reader? Will the reader’s understanding of the world be challenged, enriched, or improved?

- Experimentation: Do these poems play with words, forms, and structures? Do they seek new and inventive uses of language?

The order of poems in a modern poetry book should accomplish these five tasks. If you feel that yours does, you’re ready to start formatting and submitting your manuscript! For more on how to write a poetry book, take a look at Caitlin Scarano’s course Putting It All Together .

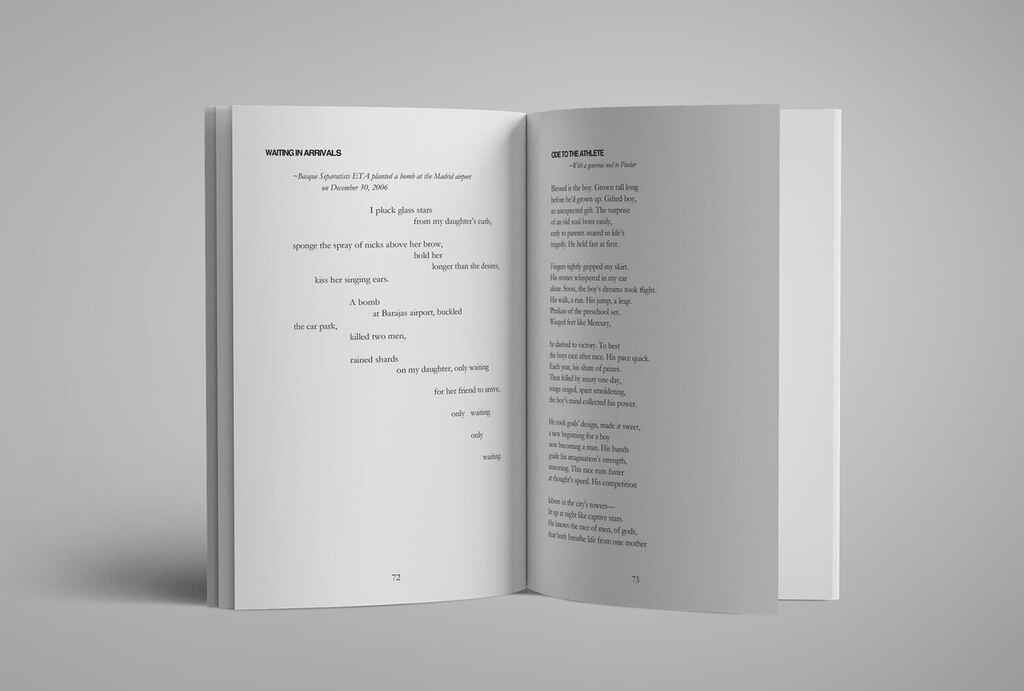

If you’ve finished writing a poetry book, this is your next step. Manuscript formatting is an essential part of learning how to write a poetry book. Take a look at our article on poetry manuscript formatting below. Additionally, you can download a pre-edited poetry manuscript at our resources page.

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

Just like learning how to write a poetry book, we’ll break down learning how to publish a poetry book into a few different facets. First, it’s important to know a bit about the world of poetry book publishers.

You know how people joke about poets not making any money? It stings a little, but it’s true—publishers do not have a whole lot of money for poets. Most new poetry books are published by independent presses, which have a small budget for acquiring new works. Poetry books have a smaller readership than fiction and nonfiction titles, so for a press to accept a poetry manuscript, that manuscript needs to have strong appeal towards the publisher’s readership.

If you’re eyeing an indie press, take a look at the previous titles they’ve published, as this can help gauge their interests in poetry, their diet for experimentation, and what their readership expects from the press.

Poets have two primary methods of publishing their poetry books:

- Contests: Poetry book publishers will often run annual contests. The contest is often helmed by a well-regarded poet who judges the finalists and selects one (sometimes more) collection to be published. The winner of this contest typically wins a small award, rarely more than $1,000.

- Open reading periods: Publishers routinely have periods where they accept new manuscripts. These periods are judged by the members of the publishing house themselves, and the publishers might accept 1 manuscript, 10, or none at all—it all depends on what they’re looking for.

Note that most contests, as well as many open reading periods, require the poet to pay a reader’s fee or contest entry fee. These fees are typically between $15-$30.

Do poets ever get a payday? Of course—just don’t expect six-figure book deals. The only publishers who can afford expensive book titles are the Big 5 (Penguin, MacMillan, HarperCollins, Hachette, Simon & Schuster). These publishers will only acquire poetry books from well-known poets, so unless you’re the U.S. Poet Laureate or a social media mogul , you won’t have much luck with these companies.

Nonetheless, building an audience for yourself as a poet and working with the right publisher will yield successful book launches, which are a vital part of sustaining your career as an author. But what are publishers looking for?

Indie book publishers don’t have much money to risk, so they’re likely to publish titles that are easy for the company to market. As a result, book publishers tend to carve certain niches in the poetry world.

How do you learn about a publisher’s marketing base? Well, you can’t, really. But you can make inferences based on the titles you read and the book publisher’s digital presence.

For example, Graywolf Press is known for publishing experimental, experiential poetry. Many of its titles are tinged with social activism, and it has the readership to match this interest: its poetic ranks include slam poets, political activists, and educators, as well as plenty of poets with degrees in English. Note the press’ mission statement : to produce “works of literature [that] nourish the spirit” from “underrepresented and diverse voices.” This tells you everything about the quality of work Graywolf expects and the voice they tend to publish; if you think you meet these expectations, you might want to submit to them!

Academic presses, which we’ll include as a subgroup of indie publishers, tend to attract academic poets. Thus, they expect a high level of attention and rigor towards the more scholarly facets of poetry: form, vocabulary, etc. Take a look at some recent publications by Yale University Press . The titles and subject matter of their poetry books tend to be erudite and didactic, and many of the names in their Younger Poets series have become celebrated in the poetry community.

Before you submit your manuscript to poetry book publishers, try to tick all of these boxes:

Here are yes or no questions that help you know if your poetry book is ready to submit to publishers or contests:

- Are you confident in the manuscript? (See: The 5 E’s)

- Have you bought and read at least 1 poetry book from this publisher?

- Some considerations: Subject matter, tone of voice, vocabulary

- Does your manuscript meet the publisher’s expectations? (These are usually included in the contest details).

- Is your manuscript properly formatted? The publisher may reject your work if it’s rife with formatting errors.

One thing we didn’t include on this checklist is the need for a social media following. Most modern poetry book competitions are judged blindly, meaning the manuscript reviewers choose a title without looking at the poet’s name. If you’re considering pitching a poetry book to an agent (which we discuss in a bit), having a following can help support your chances of getting published, since there’s a better chance that your book will be commercially successful.

Rather than pore through the many poetry book publishers currently accepting titles, it will be much easier to send you towards directories that know way more than we do.

Directories for chapbook and manuscript contests:

Poets & Writers

Ardor Lit Mag

Submittable

Directories for publishers seeking manuscripts:

Publishers Archive

Community of Literary Magazines and Presses

TCK Publishing

Directories for poetry agents:

Poets & Writers

Directory of Literary Agents (requires sign-up)

Miscellaneous :

The John Fox

The short answer is no. Few literary agents represent poets because, again, there’s little money in poetry. As a result, the poet is often their own representative, which is why many poets get their start by submitting to chapbook and manuscript contests.

The short answer is no. In fact, few literary agents represent poets.

Of course, poetry agents do exist. However, like book publishers, agents are wary of signing with new poets, unless that poet can vouch for their future literary success (previous publications, social media following, etc.). If you want to publish with the Big 5, or even with some independent publishers like Graywolf, an agent is often necessary.

Recruiting an agent has its own requirements. Reader’s Digest breaks it down pretty well at this article , but in short, you likely need to submit a query letter to the agent. This is your time to sell yourself as a writer. Lead with your best foot forward, and if an agent is looking to acquire new talent, they may just acquire you.

Self-publishing is an optional route for those learning how to publish a poetry book. Companies like Lulu , Kindle Direct Publishing , and Ingram Spark have carved a niche in the book publishing industry, allowing many poets to circumvent the traditional publishing space and put their own words in print.

Take a look at our article on self-publishing with Amazon below.

https://writers.com/self-publishing-on-amazon-pros-and-cons

In short, self-publishing is a viable option, but if you want it to be fiscally successful, you need a healthy mix of marketing savvy, business acumen, and patience.

To be frank: it is ridiculously hard for poets to get their poetry books published. There are thousands of poets with incredibly well-written manuscripts, and very few publishers able to accept those manuscripts. To give you an example: In 2023, Scribner held an open reading period, where poets could submit their manuscripts for free to the press. Submissions were capped at 300 entries. The submission window closed in under 3 minutes.

Read that again: 300 poets submitted to Scribner in under 3 minutes. Thousands more were trying to get their manuscripts in when the window closed. That is how scarce the publishing opportunities are, versus how many poets have collections they’re ready to see in print.

I recently attended the AWP conference in Kansas City, and I went to a panel on 4 debut poets’ experiences publishing their first collections. These poets, each of whom had celebrated collections and connections to the literary world, struggled for years, if not decades, to get their first collections in print. And these are poets who received their MFAs or Ph.Ds in poetry!

This isn’t to say that your collection is destined to flounder. Rather, it’s to encourage you to be patient and be enterprising. Submit to as many contests and open reading periods as your time and budget allow; in the meantime, work on publishing your poems in journals , and build an audience for yourself as a poet. Enmesh yourself in the community of poets—you might even find new publication opportunities this way. And, don’t be elitist about where you publish. It is much more important to publish with a press that cares for your work and wants to see it be successful in the world, rather than reserve your book for a publisher that might have a big name attached to it. We’re not in this for the money or the fame, we’re in it for the love of the craft.

The poetry book is just one marker of many in our careers as poets, and while the journey to publication might be frustrating, it will happen with a mix of diligence, grace, and persistence. You got this!

Learn How to Write a Poetry Book at Writers.com!

Whether you need help writing a poetry book or you’re ready to get it published, Writers.com has the resources to make it happen. Take a look at our upcoming poetry courses , and join our Facebook group for community news and feedback.

Sean Glatch

11 comments.

This seems to be about self-publishing. Is it? Do you cover anything about getting work into print, so that builds into a chapbook or book?

Thank you for writing, Laura! Here’s an article on places to submit individual poems: https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online . The text above does discuss having a poetry book conventionally published, as well.

Any tips on marketing a self-published Amazon ebook for free apart from social media? I have got my book Embracing Life by Shreya Ghosh published but don’t know how to promote it for free apart from on my social media.

[…] where to start? Here’s a little how-to guide, and some ideas where to submit your manuscript:How to publish a poetry bookWhere to submit the manuscriptContest deadlines – calendar 2021The book […]

So I’m wondering – if you publish your own book, is it acceptable etiquete to publish your poems online and build up a base of readers beforehand? Or does that violate the guidelines of this article, where you should never go public with your work?

Also, if you publish independently, do you have intellectual rights to your work? Do publishers generally retain intellectual rights?

Not only is that acceptable, it’s encouraged! Publishing in literary journals can accomplish two things. 1) It helps you build a reader base, connecting you with other poets and admirers of the form. 2) It gives you a space to promote your book after it’s published. Some literary journals will do interviews with their published poets when a poet has a book come out; even if they don’t do this, you might get journals to tweet about your book.

In short, do everything you can to build a readership, including publishing. Also try to have some form of a social media presence, if you can. And be sure to thank those literary journals in the acknowledgments section!

In general, self-published authors retain intellectual property rights over their work, though be aware that you still forfeit certain rights depending on the publisher. If you self-publish through Amazon, for example, and you get an ISBN for your book, you will not be allowed to remove the book from their marketplace or database, you can only prevent people from buying new copies.

With mainstream publishers, the share of intellectual property rights is determined by the contract you sign with them.

I hope this answers your questions. Best of luck publishing your poetry book!

Warmest, Sean Glatch

I have been writing poetry for a good number of years now, with greater than 99% of them being of a spiritual content. I have a list of about 80 people that I share my poems with, who in turn, have their circle of friends that they share with. I have been encouraged to publish my poems but I must admit, although I have toyed with the idea, figuring out how to do this has become quite overwhelming. Any advice would be appreciated. I have no clue as to what to do!!

Did you ever get a reply?

I forgot to ask; Is it recommended to have other poets critique my work to get a feel as to whether it even merits publishing? Thanks

Get into or form a Writing Group. There is no better criticism than other writers you each respect. However, there must be some rules you all follow. Sincere praise of another’s writing is desired, insincere praise is not. Grammatical correction is desired absolutely if the critic understands grammatical usage. (Hint, use Grammarly: an app that is excellent in its suggestions, but it does not always understand your particular usage. It would be nice for someone to develop a poetical grammar application that understands the nuances of all the poetical forms.)

However, you must belong to and share your writing with sincerity–no matter what form or literary type you or the other members of your group choose. Poetry is an intricate part of our learning experience and therefore has a strong influence on the form your writing will take. For example, do you remember the nursery rhymes you heard as a baby? They helped form your perceptions of the story, format, and insight that is the basis for literature.

What poets need is a Poetry Marketing Group. Successful marketing is very hard for a writer or any other entrepreneur to do for their own work. It is much easier to market other’s work than your own work. I have an MBA in marketing and have been published by a traditional business publisher, a self-publisher, and have been an industrial publisher, but even I feel uncomfortable marketing my own work. I think contracts could be developed so all involved make money (authors and marketers). Your comments?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home » Tips & Tricks » How to write a poetry book

3. Study the craft of writing poems

As with any creative field, learning the traditions and techniques of poetry will improve your writing skills. Take some time to immerse yourself in the craft of poetry. You may know instantly whether or not you like a particular poem, but do you know what makes the writing effective? Think about the way stanzas, enjambment, meter (or rhythm), diction, imagery, similes, and metaphors function in a poem you love. If that sounds like a lot, focus on one poetic element at a time—observe how it works in poems you read and practice using it in your own writing. The Poetry Foundation has a wonderful glossary of poetic terms to get you started, along with daily poems, an online magazine, podcasts, and literary reviews.

4. Experiment with different forms

Most writers are familiar with poems that feature rhyming patterns, like the sonnet or haiku form. But have you ever tried writing a sestina or villanelle? Do you typically write in short, unpunctuated lines or long stanzas full of complete sentences? A lot of contemporary poetry is written in free verse (without a rhyme structure or regular meter). There’s plenty of room for experimentation in the world of poetry, while still making use of key literary techniques. As a challenge, try writing poems that look and sound different from the ones you typically write. Taking creative risks can lead to great discoveries!

5. Avoid clichés

This writing tip might summon up memories from English class, but it’s sound advice for writers at every level. You know a clichéd phrase when you see it or hear it, which is proof that it’s overused and unoriginal. Examples include: “fluffy as a cloud,” “at the speed of light,” “clear blue water,” “scared to death,” “the writing on the wall,” and “lasted an eternity.” Get in the habit of checking your poems for such hackneyed phrases and removing them. Poetry derives its power from the creative use of language, so choose your words carefully.

6. Ask for feedback

Opening yourself up to positive and negative feedback is part of the creative process when writing a poetry book. If the thought of getting constructive criticism makes you recoil, remember that growing and improving as a writer involves assessing your work. Successful and experienced poets need help editing, and so will you. Try joining a poetry community online or creating a writing group at your local bookstore or café. If you look around, you will discover poets just like you who want to become better writers, exchange work, and support one another.

7. Give yourself time to revise

It’s natural to latch on to that surge of creative energy when you’ve just written something new, and you love it, and wouldn’t change a thing! Occasionally you might keep the first draft as is, but more often, you’ll want to step away and return to it another day with fresh eyes. After reflection, you may decide to add another whole page or cut repetitive, vague lines to make the poem even tighter and stronger.

8. Choose your best work

It can be tempting to include every poem you’ve ever written, especially if this is your first poetry book. However, any weak poem you leave in will detract from the best ones in the book. To showcase the writing, you are most proud of, you’ll probably need to cut some poems (You can always send these to friends, submit them to journals, or put them in your next collection!). For a full-length poetry book, aim to collect around 40 to 70 pages of polished work. If your stack of poems is on the small side, don’t stress—publish a chapbook instead! Chapbooks are shorter collections of poems that average between 20 to 40 pages, and they make a great first book project.

9. Organize your poems

Your poetry book should be a collection of poems that work together or feel related in some way. Maybe the book centers around a particular theme, form, style, or series of life events. It’s your creation, so you decide what connects the individual poems and how they should be sequenced. Think of the first poem in your book as an opening act. Which poem best invites readers into your world and sets up the entire book? Similarly, what is the last poem (the final image!) that you want to impart on your reader?

10. Select a book title

Choosing a title for your book is an exciting moment! If you need ideas, consider naming the book after one of your strongest poems or borrowing a favorite line or image from the collection. You want your poetry book to capture the imagination of a new reader, so don’t settle for generic titles like “Selected Works” or “Poetry by …” Instead, give your poetry collection a unique title that is intriguing and reflects your own poetic language.

Ready to see your collection of poems in print? Keep the creative momentum going with tips on how to self-publish your poetry book with Blurb.

This is a unique website which will require a more modern browser to work! Please upgrade today!

This is a modern website which will require Javascript to work.

Please turn it on!

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

5 Writers Who Blur the Boundary Between Poetry and Essay

"poets are the hoarders of the literary world".

There is a Bernadette Mayer writing exercise that suggests attempting to flood the brain with ideas from varying sources, then writing it all down, without looking at the page or what spreads over it. I have attempted this exercise multiple times, with multiple sources, and what I love about it—along with many of Mayer’s other 81 prompts—is that what comes out can literally take any form. The form is not dictated by the content I read, nor the rules of the exercise. The information I collect prior to writing may be entirely disparate, seemingly unrelated, but through the writing, it begins to take shape, and links are found. In the process of communicating information in a lyric way, barriers to form withheld, I am able to develop a richer portrait of what thinking really looks like.

I heard someone say once that poets are the hoarders of the literary world: collectors of facts, dates, quotes, newspaper headlines, ticket stubs, and love letters. Indeed, another of Mayer’s prompts is to keep a diary, or diar ies , of such useful things. As these journal pages begin to overflow, content spilling over the borders, the writing becomes something we might not always call a poem. Reflecting on his poetry collection The Little Edges and a book of essays The Service Porch , both of which appeared in 2016, poet and critic Fred Moten said , “The line between the criticism and the poetry is sort of blurry. I got some stuff in the poems that probably could’ve been collected with the essays.”

There is a long-standing tradition of poets who have refused genre, or reinvented it, and who continue to push the boundaries of form. Here are five, but just a cursory glance into any of their work will lead you to uncover many more.

Jenny Boully

The first essay in Jenny Boully’s latest collection Betwixt and Between: Essays on the Writing Life, published last month, is a journey into two illusive linguistic temporalities: “the future imagined and the past imagined. ” By positioning the reader in a space of hypothesis, Boully tests the limits of memory and lived experience, never quite allowing her reader to land on stable footing. With this linguistic trick, a redefinition of what is the personal begins to emerge.

Throughout her work, Boully is interested in reorienting the role of the reader from passive to participatory and reorienting the structure of the text from chronological to sensory. In an introduction to Boully’s work, Mary Jo Bang writes , “She uses form in a way that undercuts our every expectation based on previous encounters with poetry.” It’s no wonder that excerpts from her first book The Body , written as footnotes to an imaginary text, were included in both John D’Agata’s The Next American Essay and The Best American Poetry 2002 .

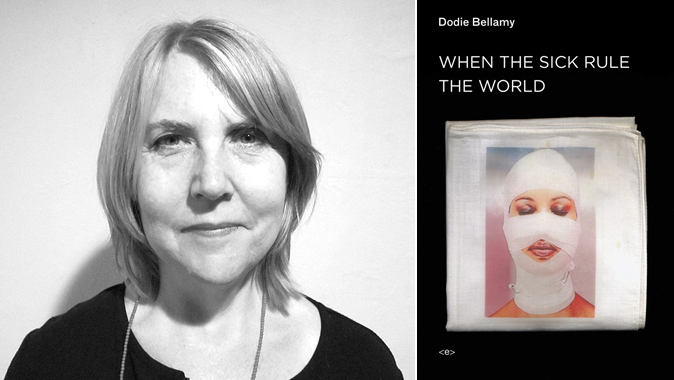

Dodie Bellamy

Dodie Bellamy is a seamstress of language. Her work stretches the definitions of narrative writing by incorporating literary appropriation, cut-ups, collage, and détournement, or the act of turning a recognizable cultural product on itself, a technique developed by the Situationist International in the 1950s. Her poetic “cunt ups” take works of the traditional poetic canon and reinvent them with a contemporary feminist voice, directly splicing the historic masculine texts with pornographic imagery. The 2013 collection Cunt Norton employs the original language of 33 canonical poets, twisting them into erotic poems as an act of love for her predecessors. “These patriarchal voices that threatened to erase me—of course I love them as well,” Bellamy wrote of the work . Her experiments began to take a more prosaic form as she desired further space for her content. “I was writing linked poems that kept getting longer and more narrative,” she said in an interview .

Due to her inventive and often hysterical treatment of language, Bellamy’s voice is engaging on any topic. The themes she tackles in her collected essays When the Sick Rule the World range from the gentrification of San Francisco, her experiences with a women’s writing group and a moving tribute to the late equally inventive writer Kathy Acker, in the form of a catalogue of the contents of her wardrobe.

Claudia Rankine

When Claudia Rankine’s Citizen won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the judges’ citation read, in part, “It’s not (just) poetry.” The prose-poetry hybrid is a current throughout her work; her previous poetry title Don’t Let Me Be Lonely was described, alongside Citizen , as “lyric essays” in the The New York Review of Books . Rankine’s work uses investigative tools of poetry to probe what it means to be human and to encourage readers to examine their personal responsibility to others. Through experiments in form, she highlights the dangers of lazy classification of people and experiences; her words in any medium provoke self-reflection.

In Citizen , a 2015 essay on Serena Williams finds a comfortable home alongside prose and list poems. With her employment of the second person throughout the collection, Rankine prompts her readers to enter into the very experiences she is describing, whether they are wholly familiar or not. As such, her approach is in equal measure confrontational and humanizing.

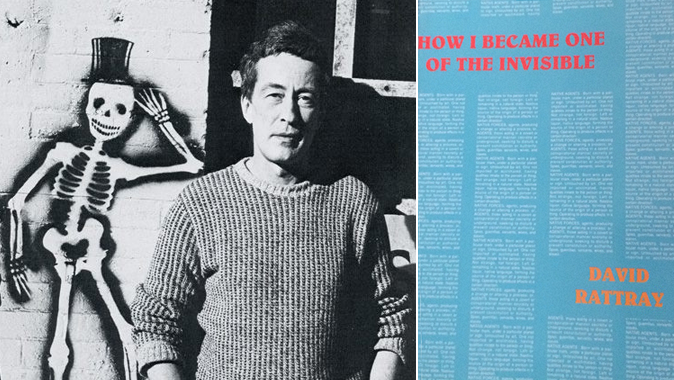

David Rattray

When the poet, critic, and renowned translator David Rattray passed away at the age of 57 in 1993, the experimental writer Lynn Tillman wrote , “He swept us away also with his ‘bad attitude,’ his insubordination to authority and to the authority of what he knew.” This was true not just in the manner he lived his life, but also how he captured life in text. A principle translator of Antonin Artaud, Rattray’s own poems display a diary-like quality: they are grand narrations stuffed full of dates, places, people.

A collection of essays and stories exploring his relationship to close friends, grief, drugs, travel, and literature called How I Became One of the Invisible was put together by Chris Kraus just before his death. Through narratives that are at once breathless and directional, and full of poetic references and quotes, Rattray reveals his deep feelings for those with whom he shared his life. “He believed people were gems, precious, and treated them accordingly,” Betsy Sussler wrote , following his passing. And so too did he treat his words, allowing us to enter into his world imbued with sensitivity.

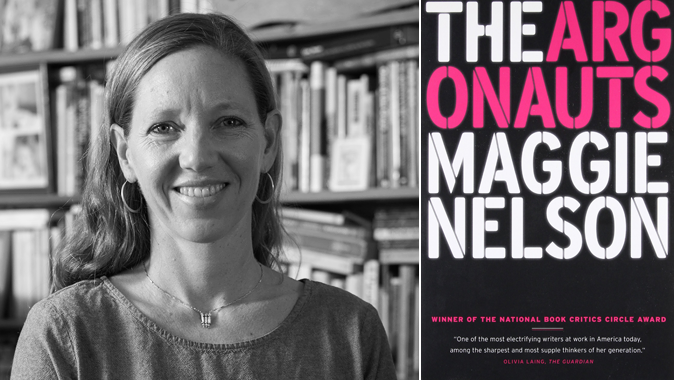

Maggie Nelson

Asked in an interview by Emily Gould as to how she decides on which genre(s) she will employ when writing a new book, Maggie Nelson replied , “Genre, for me, is determined by the unfolding of my interests, which is unknowable at a projects’ start.” Her defiance of category is not only evident in her bibliography, but in the bibliography of each book which makes it up. Bluets , which began as an investigation into the color blue and its varying manifestations throughout history, became a book of prose poems. The Art of Cruelty , a personal reflection on the employment of violence in art, became a book of academic criticism. Begun as a work of criticism, The Argonauts became a personal memoir, with its background research spilling, literally, into the margins. “I find my way to the right tone, idiom, form or set of subjects as I bumble along,” Nelson says.

It is her very adaptability of form and expression that has become one of her signature attributes, despite the literary world’s continued insistence on writerly classification, and in turn mimics the fluidity of her subjects. Hilton Als writes , “It’s Nelson’s articulation of her many selves . . . that makes her readers feel hopeful.”

Listen: Claudia Rankine talks to Paul Holdengräber about objectifying the moment, investigating a subject, and accidental stalking.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Ruby Brunton

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

12 Famous Authors at Work With Their Dogs

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

5 of the best books on writing poetry

By BBC Maestro

- Share on Facebook

- Share via email

We all need inspiration from time to time, particularly when it comes to taking up a creative endeavour like writing poetry.

In this article, we’ve rounded up a list of the best books on writing poetry to help you kickstart your poetry writing journey or spruce up your current practice.

- Best books on writing poetry

- 1. A Poetry Handbook

- 2. Answering Back: Living poets reply to the poetry of the past

- 3. The Practising Poet: Writing beyond the basics

- 4. How to write poetry: A guided journal with prompts

- 5. The Poets Companionship: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry

5 books on writing poetry

You may be waiting for that spark of inspiration to hit. Or perhaps you’re yearning for some solid guidance on how to structure your next poem. Whatever it is that’s brought you here – you certainly aren’t alone.

Plenty of poets have sought to identify the perfect conditions for a new idea to strike or attempted to create a winning formula to ace the writing process. And luckily, many of them have decided to share their learnings to help poets like you thrive.

We’ve rounded up 5 popular books on writing poetry to help address some of the challenges below.

1. A Poetry Handbook by Mary Oliver

If it’s some gentle beginner’s guidance on how to write a poem you’re after, Mary Oliver should be able to provide you with what you’re looking for with this useful handbook.

Here you’ll find her breakdown of poetry’s basics – from different poetic forms and language techniques to practical tips on the creative process – like the importance of workshopping your pieces and the value solitude can bring to your writing too.

The latter is something many poets swear by, including Carol Ann Duffy. “I’ve learnt to value silence. I’ve learnt to value thinking, reading, contemplating, rather than rushing straight to the blank page,” she says in her BBC Maestro poetry course.

2. Answering Back: Living poets reply to the poetry of the past edited by Carol Ann Duffy

If you’re looking to kick a creative block, this anthology by the former Poet Laureate might just do the trick. It features a selection of popular modern-day poets (like Simon Armitage, Seamus Heaney and emerging poets like Helen Mort, to name a few) responding to certain works of classic poets (think Wordsworth, Shakespeare and Tennyson).

Each poet was tasked with choosing any poem that compelled them in some way and responding to it with one of their own. Some of the works are clearly direct responses to the themes and ideas presented in the original poems whilst others are more subtle and offer a new perspective. It’s an exercise that can really help stir up some inspiration to write, and it’s one that Carol Ann Duffy tasks viewers of her online poetry course to do too.

Inspiration, as Picasso said, will come but it must find you working. Carol Ann Duffy, Poet

3. The Practising Poet: Writing beyond the basics by Diane Lockward

Whether you’re working on your second anthology, or this is the first time you’re coming to the pages, Lockward’s The Practicing Poet is the perfect companion for poets of all levels.

In this poetry book, you’ll find ten sections that break down different parts of the writing process. From helping writers generate their own ideas and tackling the editing process to getting your work published, it contains practical advice for each stage of the journey you can bring to your work – whether it’s love poetry , dark poetry or another genre that excites you.

4. How to write poetry: A guided journal with prompts by Christopher Salerno and Kelsea Habecker

Hungry to get writing immediately? Packed with writing prompts and exercises, Salerno and Habecker’s book should have you writing from the moment you pick it up.

The workbook encourages writers to crack open their creativity – prompting them to assess rhyme and meter, language and form in innovative ways in the hope to craft something compelling. If you’re a beginner, it’s a great guide to help you get into the habit of writing regularly. And for those poetry experts, it may help provide a new framework to inspire your next great idea.

5. The Poets Companionship: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry by Kim Addonizio and Doiranne Laux

For those poets who need a confidence boost from time to time, this book may well be your new trusty companion.

Expect to come across a range of brilliant essays on all things poetry, like forming exciting ideas and navigating classic poetry techniques. At the same time, many appreciate this book for its comforting approach to the entire writing poetry process – acknowledging the inevitable self-doubt, the challenges of writing in a hyper-digital era and the forever rocky stability of a writing career. Even better – it encourages you to tackle it all at your own pace too.

Even if you have no idea where to start, hopefully, there’s something in here to help get you going. Remind yourself of the reasons why writing poetry interests you. Maybe you’re looking for a new way to express your thoughts and ideas, or you feel you have something important to say.

If so, remember the words of Carol Ann Duffy, “the poet must feel that they have something to give,” says Carol Ann. Keen to learn more? Take a look at her BBC Maestro course, Writing Poetry .

Thanks for signing up

Your unique discount code is on it's way to your inbox

Oops! Something went wrong

Please try again later

Get a free lesson from Carol Ann Duffy

Learn how to take inspiration from the world around you

By joining the mailing list I consent to my personal data being processed by Maestro Media in accordance with the privacy notice .

See related courses

Carol Ann Duffy

Writing Poetry

Writing Love Stories

Storytelling

Give the gift of knowledge

Surprise a special someone with a year's access to BBC Maestro or gift them a single course.

Thanks for signing up to receive your free lessons

Check your inbox - they’re on the way!

Get started with a free lesson

from poet, Carol Ann Duffy

9 Essential Writing Books for Any Poet

If you’re looking to improve your craft, reading is just as important as writing. While reading poetry collections can teach you plenty, it’s also important to hear from poets themselves. Those ready to get into the nitty-gritty may just find that books about craft are as entertaining as they are informative. To help you find a great place to start, we’ve created a list of 9 essential books for poets and writers.

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

One of the most famous writing guides of all time, Lamott’s Bird by Bird provides wry, down-to-earth advice for writers of all ages and abilities. From writers’ block to finding your voice to the ups and downs of publishing, there’s something in here for everyone.

The Practicing Poet by Diane Lockward

If you’re ready to push beyond the basics in your poetry practice, The Practicing Poet is the guidebook for you. Split into 10 neat sections, the book offers 30 brief craft essays paired with a model poem and an analysis of it. Lockward’s dissection of each poem and what makes it tick provides readers with clear instructions on building their own intricate, beautiful poems.

On Writing Well by William Zinsser

If you’re in the market for sound advice, clear writing, and concision, Zinsser is your man. Though the book is not written specifically for poets, On Writing Well provides guidelines for improvement throughout your writing (from emails to memoirs to, yes, even your poems). He also includes pages of the original manuscript to show what’s been cut, giving readers the courage to be bold and ruthless when boiling works down to the essentials only.

Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury

Take a peek behind the curtain and get a glimpse of the wisdom, experience, and excitement that award-winning author Ray Bradbury brings to the page. Pulling from a lifetime of writing, Bradbury offers practical tips on the craft of writing—from finding original ideas to developing your voice, and beyond.

Writing Poetry to Save Your Life by Maria Mazziotti Gillan

A combination of author Gillan’s personal story and advice for writers in all stages of development, Writing Poetry to Save Your Life is a friendly, encouraging read. Without giving too much away, we’ll tell you that Gillan calls your inner critic “the crow” and offers tips on how to silence it to fully harness the power of words to express yourself.

A Poetry Handbook by Mary Oliver

This witty and passionate guide to understanding and writing poetry is the perfect entry point for those new to the craft, but it’s also a great refresher for seasoned poets. Using poems by Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, and other greats as examples, Oliver unpacks the inner workings of matter and rhyme, form and diction, sound and sense.

The Poetry Home Repair Manual by Ted Kooser

Practical, tangible, and succinct, former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser pins down the essentials of poetry in this handbook by beginning with the most important piece of the puzzle: why . What is the purpose of poetry? Why do we write? Starting from here, Kooser teaches how to start, shape, and strengthen your poems overall.

The Poet’s Companion by Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux

For a mix of essays, exercises, and advice, The Poet’s Companion might just be your best friend. Though the book deals with topics like self-doubt and publishing in the electronic age, Addonizio and Laux don’t skim over the nuts and bolts of writing in the process. With one topic per chapter, it’s easy to find what you’re looking for in this helpful guide.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

How to Stay on Track with Your Writing Goals

How to Memorize Poems for Confidence and Cognitive Power

Summer Prompts to Brighten Up Your Poetry

The Dos and Don’ts of Writing a Poetry Book

by GetPublished | Oct 13, 2022 | Writing

Someone with the heart of a poet has probably filled a slew of notebooks with their poetry. Some poets may even sketch drawings or thought trees to flesh out their poems as part of their writing process. Once a sizable number of poems have been penned, the idea of writing and publishing a poetry book may come to mind. This handy guide explains the dos and don’ts of writing a poetry book and can be useful to the budding poet whose sights are set on authoring a collection of poetry.

Popular Styles of Writing Poetry

What makes poetry such an intriguing writing form is its wide range of styles. Whether the poem is a vehicle for storytelling or a foray into the esoteric, the poetry style that a writer uses shapes the rhythm and mood of the individual poem.

Consider the many styles of writing poetry:

Haiku, a short form of poetry, originated in Japan in the 1700s. Haiku poems contain only three lines and a total of seventeen syllables. The syllables are ordered in patterns of 5-7-5, and the words are unrhymed.

Free verse is a style of poetry that stems from the French “vers libre.” A free verse poem has no set syncopation or rhythm, reflecting the natural patterns of speech. The free verse style follows no customary rules of poetry and is not designed to rhyme. Modern poets enjoy the creative freedom this form of poetry allows.

The sonnet has Italian roots and features a fourteen-line poem that follows a prescribed format. A sonnet includes two stanzas, one containing eight lines and one containing six lines, and utilizes one of several rhyme schemes.

The limerick originated in 18th-century England and is known for being humorous and even rude. The limerick contains five lines and follows a set rhyming pattern, with lines one, two, and five having eight syllables, and lines three and four having five syllables.

Although the ode style of poetry is often attributed to England, it actually originated in ancient Greece. The ode is typically a dedication to or celebration of something from the past that the author feels is meaningful and praiseworthy. It has a three-part structure: the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode.

Ballads are of French origin, before taking root in England and Ireland in the Middle Ages. Ballads are narrative poems or folk songs that feature emotional storytelling using four-line stanzas in 4-3-4-3 rhythms.

Now that you’re familiar with the different types of poetry, let’s move on to the writing process dos and don’ts.

Dos of Writing a Poetry Book

As you embark on your poetry book project, consider these important dos:

- Write a lot of poems. A typical poetry collection will include 30-100 poems, so the more poems you write the more you will have to select from. Pick your strongest poems to compile into a poetry book.

- Decide on your writing style. When considering the styles of writing poetry, it is best to use one style throughout. This helps you create a cohesive reading experience.

- Organize your poems. When deciding on the order of your poems, strive for balance throughout the collection, versus placing all the strongest poems at the beginning. Poems should also relate somehow to one another, or even follow the evolution of a particular theme.

- Edit your collection of poems. Correct all typos or syntax issues by carefully editing the poetry manuscript repeatedly.

- Design your pages. The interior design of your poetry collection is a central feature of its overall visual appeal. Formatting pages of poetry is much less rigid than designing a book, which allows the writer to be creative. A collection of poems may even include simple hand-drawn illustrations to complement individual poems.

Don’ts of Writing a Poetry Book

Keep these don’ts in mind as you write your poetry book:

- Don’t allow room for errors. Even the most astute writer will miss their own typos. Don’t risk making this mistake by having a professional editor do the final editing.

- Don’t be afraid to share your thoughts. The essence of good poetry is the author’s willingness to open up and reveal what is in their heart and mind. Draw from personal experiences to take the reader on a journey.

- Don’t make your book too long. An average poetry book will have between 40-80 pages or up to 100 poems.

- Don’t attempt to be trendy. While it may be tempting to follow the current poetry trends, resist that impulse and focus on creating a collection of innovative and unique poems. Experienced poets know that adhering to trends may result in their books feeling dated at some point.

- Don’t forget your audience. Remember that you are speaking to a particular audience through your poetry. As you select the poems for your collection, keep that audience persona firmly in mind.

We hope that our advice for writers is helpful in your poetry writing journey. Almost finished with writing a poetry collection? Contact Gatekeeper Press for professional editing and cover design services .

Publish Your Poetry Book With Gatekeeper Press

Creating a book of poetry can be tricky. Why go it alone when you can team up with the professionals at Gatekeeper Press to produce a polished and well-designed poetry collection? When you are ready to self-publish your poetry book , give us a call at 866-535-0913 or contact us online !

Free Consultation

- Unconventional writing techniques to help you out of a creative rut

- Joanne Chestnut Publishing Journey Q&A

- Goblin Queen Publishing Journey Q&A

- Does Your Manuscript Spark Joy?

- Capri Compton Publishing Journey Q&A

- Author Q&A (22)

- Editing (18)

- Making Money (7)

- Marketing (13)

- Publishing (62)

- Publishing Journey Q&A (10)

- Uncategorized (2)

- Writing (58)

Learn How to Write Poetry with the 17 Best Books on Writing Poetry

Are you looking to learn how to write poetry? Fear not: you’re in the right place. This epic list of the 17 best books on writing poetry has you covered. Whether you’re looking for poetry books for beginners, the best poetry journals, or want to level up your poetry writing skills as an intermediate to advanced poet, these 17 essential books about learning poetry writing has something for everyone.

For more books on creative writing, be sure to check out Broke by Books’ list of the 20 + best books on creative writing .

The 20+ Best Books on Creative Writing

This post contains affiliate links

The 17 Best Books to Learn How to Write Poetry

Blackout poetry journal: poetic therapy by kathryn maloney.

One of the most popular forms of poetry today is the art of blackout poetry, in which poets scratch or blackout text to reveal a poem in the words that remain. Get started with Kathryn Maloney’s Blackout Poetry Journal , which includes excerpts from random books in the public domain. This poetry writing journal is a great way to learn how to get started with writing blackout poetry. Start with the second book in the series for a variety of source texts to black out, rather than working with one full book.

How to read it: Purchase Blackout Poetry Journal on Amazon

The complete rhyming dictionary by clement wood.

A few years ago, I was working on a collection of children’s poetry. I loved exploring different rhyming poetic forms, like the limerick and the double dactyl. I purchased Clement Wood’s The Complete Rhyming Dictionary and was in good hands. This complete rhyming dictionary is a must-have for anyone writing rhyming poetry. What was so impressive was how comprehensive this dictionary was its depth, with over 60,000 entries, of obscure and popular words alike. You’ll easily be able to search by one-, two-, and three-syllable rhymes.

How to read it: Purchase The Complete Rhyming Dictionary on Amazon

The everything writing poetry book by tina d. eliopulos and todd scott moffett.

This comprehensive and easily approachable guide to writing poetry has all the knowledge you need to get started with writing poetry. You’ll learn how to write poetry, starting by getting up to speed with styles, structures, form, and expression. This unpretentious book about how to write poetry for beginners will have you penning verse in no time. I especially appreciate deep-dive chapters on the sound of poetry, poetic language, and meter. The Everything Writing Poetry Book packs a lot of instruction in one book and is definitely the equivalent of an intro to poetry writing course you’d get in college.

How to read it: Purchase The Everything Writing Poetry Book on Amazon

How to write poetry: a guided journal with prompts by christopher salerno and kelsea habecker.

There’s no better to get started with writing poetry than jumping in and getting your page dirty. In How to Write Poetry: A Guided Journal with Prompts , you’ll be taken through the process of writing poetry. This guided poetry journal pairs lessons on rhyme, meter, tone, persona, as well as movement-specific topics like protest poetry and object poetry, with practical prompts and space to test out what you’ve learned. By the time you’ve worked through this poetry writing workbook, you’ll be well on your way to being a poet.

How to read it: Purchase How to Write Poetry: A Guided Journal with Prompts on Amazon

A little book on form by robert hass.

This book is a little misleading. Yes, it’s a book on poetic form. But it’s by no means a “little book.” And you know what? That’s totally okay. I’m happy to learn how to write poetry with this guide to poetic form authored by the Pulitzer Prize-winning, National Book Award-winning and former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass. And there’s definitely a lot of wisdom on writing poetry in this essential book on how to write poetry. You’ll learn the core poetic forms, from ones you’ve heard of, like sonnets, with more obscure forms like the ode, the elegy, and Georgic. Yes: this definitive book on form belongs in the library of any poet.

How to read it: Purchase A Little Book on Form on Amazon

Merriam-webster’s rhyming dictionary by merriam webster.

Writing rhyming poetry? Get all the words you need with Merriam-Webster’s Rhyming Dictionary . This comprehensive rhyming dictionary counts more than 70,000 rhyming words, as well as an alphabetical listing of rhyming sounds plus pronunciation for each entry. Brand names are also included for those looking to rhyme with proper nouns.

How to read it: Purchase Merriam-Webster’s Rhyming Dictionary

My poetry journal by pretty nifty publishing.

This poetry writing journal will teach you how to write poetry in a jiffy. My Poetry Journal contains 48 creative prompts about a variety of topics—from fairy tale characters to giving thanks to snowflakes—and plenty of blank space to get to work on converting your inspiration into poems. This poetry writing workbook is a great book for learning how to write poetry.

How to read it: Purchase My Poetry Journal on Amazon

One poem a day by nadia hayes.

Poetry writing for beginners starts with making writing poems a daily habit. Get started with writing poetry with Nadia Hayes’ One Poem a Day . This poetry writing workbook includes creative prompts—like finishing a sonnet, filling in the blanks of a partially completed poem, penning haiku, and writing free verse—and plenty of space to scratch out your own poems.

How to read it: Purchase One Poem a Day on Amazon

The poet’s companion by kim addonizio and dorianne laux.