Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Anatomy & Physiology — Childbirth

Essays on Childbirth

Reviewing different childbirth techniques from several countries, research on the modern state of the childbirth, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Effects of Acupressure on Labor Pains During Childbirth

Medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth: the general goals and performance, defying nature: choosing the sex of an unborn baby is wrong , the factors of postpartum depression, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Child Birth

Evaluation on the decision on the life choice of having children or not, the role and significance of contraception in modern societies, differences and similarities in birth rituals and beliefs of the samoans and pygmies, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Analysis of Margaret Sanger’s Speech on Birth Control

The intervention birth plan review, preimplantation and stages of fetus development, life beginning & fertalization, women’s age at first child’s birth, the importance and major developments in neonatology, the positive outcomes of childbirth at an older age, mary breckinridge and the history of nurse-midwifery, the efficacy of telephone-based lactation counseling: literature review, the effectiveness of birth control, the benefits of over the counter birth control, the population puzzle: understanding total fertility rate, the legal landscape of surrogacy: complexities and considerations, home births and societal perceptions, women's empowerment and choice in birth practices, reclaiming birth: the comprehensive exploration of home births, relevant topics.

- Human Physiology

- Cardiovascular System

- Digestive System

- Human Anatomy

- Homeostasis

- Pathophysiology

- Human Brain

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Activities /

Making childbirth a positive experience

The clinical management of labour and childbirth is well understood, but not enough attention is given to making women feel safe, comfortable and positive about their experience.

As well as providing essential information on clinical requirements for preventing and managing maternal mortality and morbidity, WHO prioritises the psychological and emotional needs of women giving birth.

In some settings, women are receiving too many interventions too late; in other settings women receive too many interventions that they may not need, too soon. WHO addresses safe and appropriate use of caesarean sections, promoting an environment that involves women in decision making and averts mistreatment during childbirth in health facilities.

Maternal health mirrors the gap between the rich and the poor. WHO insists that a positive childbirth experience should meet a woman’s personal and sociocultural beliefs and expectations in every setting.

This includes giving birth to a healthy baby in a clinically and psychologically safe environment, assisted by a kind and technically competent health care provider.

Countries commit to recover lost progress in maternal, newborn & child survival

New series highlights the importance of a positive postnatal experience for all women and newborns

More than a third of women experience lasting health problems after childbirth, new research shows

Climate change is an urgent threat to pregnant women and children

Relevant publications

WHO labour care guide: user’s manual

The WHO Labour Care Guide is a tool that aims to support good-quality, evidence-based, respectful care during labour and childbirth, irrespective of the...

WHO recommendations: non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections

Caesarean section is a surgical procedure that can effectively prevent maternal and newborn mortality when used for medically indicated reasons. Caesarean section...

WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience

This up-to-date, comprehensive and consolidated guideline on essential intrapartum care brings together new and existing WHO recommendations that, when...

Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: A guide for essential practice (3rd edition)

Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice (3rd edition) (PCPNC), has been updated to include recommendations...

Infographics

All women have a right to a positive childbirth experience

Labour progression at 1 cm/hr during the active first stage may be unrealistic for some

Every birth is unique

WHO Labour Care Guide to support intrapartum care for a positive birth experience

Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience

Related work.

Strengthening quality midwifery for all mothers and newborns

Related WHO Teams

Related health topics

Maternal health

Newborn health

IELTS Essay: Childbirth

by Dave | Real Past Tests | 8 Comments

This is an IELTS writing task 2 sample answer essay on the topic of childbirth and advantages and disadvantages of having children when older from the real IELTS exam.

Please consider supporting me on Patreon.com/howtodoielts to receive my exclusive IELTS Ebooks – you can even sign up for private live lessons with me!

People nowadays tend to have children at older ages.

Do the advantages of this outweigh the disadvantages?

There are growing numbers of men and women choosing to have children later in life these days. In my opinion, the financial advantages of this trend far outweigh any perceived downsides.

The most significant tradeoffs of this relate to opportunity and maturity. Many individuals decide early on in their career to wait until their mid to late 30s to have children. The natural risk here is that if the relationship ends before that point or they then have trouble conceiving, they may end up childless. This possibility is lower today due to advances in fertility science but still exists. Furthermore, having children is a maturing experience. If an individual waits until late in life to raise a child, then they delay the experience gained and may later regret their decision. Most parents would openly admit that parenthood is a life-altering milestone and defining moment of adulthood.

Nonetheless, the disadvantages detailed above pale in comparison to the economic merits of delaying childbirth. Firstly, most young parents are not in an ideal situation in their career. Many working parents earn low salaries and work long hours. Once they have a child that means the majority of their day is occupied and they may feel trapped and overburdened. It is then difficult to switch careers or move to a new location as well as afford all the expenses incumbent on parents. This often results in parents becoming resentful and projecting their animosity towards their children or significant other. In contrast, parents who are firmly established in their careers, earn decent salaries, and have savings set aside have both the time and energy to devote to raising their children well without having to stress about making ends meet.

In conclusion, despite marginal risks concerning the opportunity and experience, it is an overall positive for financial reasons that many prospective parents are putting off childbirth. Therefore, this trend should be welcomed and encouraged.

1. There are growing numbers of men and women choosing to have children later in life these days. 2. In my opinion, the financial advantages of this trend far outweigh any perceived downsides.

- Paraphrase the overall essay topic.

- Write a clear opinion. Read more about introductions here .

1. The most significant tradeoffs of this relate to opportunity and maturity. 2. Many individuals decide early on in their career to wait until their mid to late 30s to have children. 3. The natural risk here is that if the relationship ends before that point or they then have trouble conceiving, they may end up childless. 4. This possibility is lower today due to advances in fertility science but still exists. 5. Furthermore, having children is a maturing experience. 6. If an individual waits until late in life to raise a child, then they delay the experience gained and may later regret their decision. 7. Most parents would openly admit that parenthood is a life-altering milestone and defining moment of adulthood.

- Write a topic sentence with a clear main idea at the end.

- Explain your main idea.

- Develop it with specific examples.

- Keep developing it fully.

- Stay focused on the same main idea.

- Use hypotheticals.

- Conclude with a strong statement.

1. Nonetheless, the disadvantages detailed above pale in comparison to the economic merits of delaying childbirth. 2. Firstly, most young parents are not in an ideal situation in their career. Many working parents earn low salaries and work long hours. 3. Once they have a child that means the majority of their day is occupied and they may feel trapped and overburdened. 4. It is then difficult to switch careers or move to a new location as well as afford all the expenses incumbent on parents. 5. This often results in parents becoming resentful and projecting their animosity towards their children or significant other. 6. In contrast, parents who are firmly established in their careers, earn decent salaries, and have savings set aside have both the time and energy to devote to raising their children well without having to stress about making ends meet.

- Write a new topic sentence with a new main idea at the end.

- Explain your new main idea.

- Include specific details and examples.

- Continue developing it…

- as fully as possible!

- Vary long and short sentences.

1. In conclusion, despite marginal risks concerning the opportunity and experience, it is an overall positive for financial reasons that many prospective parents are putting off childbirth. 2. Therefore, this trend should be welcomed and encouraged.

- Summarise your main ideas.

- Include a final thought. Read more about conclusions here .

What do the words in bold below mean? Make some notes on paper to aid memory and then check below.

There are growing numbers of men and women choosing to have children later in life these days. In my opinion, the financial advantages of this trend far outweigh any perceived downsides .

The most significant tradeoffs of this relate to opportunity and maturity . Many individuals decide early on in their career to wait until their mid to late 30s to have children. The natural risk here is that if the relationship ends before that point or they then have trouble conceiving , they may end up childless . This possibility is lower today due to advances in fertility science but still exists. Furthermore , having children is a maturing experience . If an individual waits until late in life to raise a child , then they delay the experience gained and may later regret their decision. Most parents would openly admit that parenthood is a life-altering milestone and defining moment of adulthood .

Nonetheless , the disadvantages detailed above pale in comparison to the economic merits of delaying childbirth . Firstly, most young parents are not in an ideal situation in their career. Many working parents earn low salaries and work long hours . Once they have a child that means the majority of their day is occupied and they may feel trapped and overburdened . It is then difficult to switch careers or move to a new location as well as afford all the expenses incumbent on parents. This often results in parents becoming resentful and projecting their animosity towards their children or significant other . In contrast, parents who are firmly established in their careers, earn decent salaries , and have savings set aside have both the time and energy to devote to raising their children well without having to stress about making ends meet .

In conclusion, despite marginal risks concerning the opportunity and experience, it is an overall positive for financial reasons that many prospective parents are putting off childbirth . Therefore , this trend should be welcomed and encouraged .

For extra practice, write an antonym (opposite word) on a piece of paper to help you remember the new vocabulary:

growing numbers more and more people

later in life when they are older

financial advantages good for your money

trend pattern

far outweigh are much stronger than

perceived downsides apparent disadvantages

significant tradeoffs major downsides

opportunity chance

maturity experience

decide early on choose from the beginning

mid to late 30s 35 – 40 years old

natural risk obvious threat

before that point prior to that

trouble conceiving difficulty having kids

may end up childless might finally not have kids

possibility chance

advances developments

fertility science medicine related to having kids

furthermore moreover

maturing experience makes you more like an adult

raise a child help a kid grow up

delay wait until later

regret wish it had been different

openly admit honestly say

parenthood being a parent

life-altering milestone significant moment in life

defining moment significant time

adulthood being an adult

nonetheless regardless

detailed above described over

pale in comparison to not as important as

economic merits helps you make money

delaying childbirth waiting until later to have kids

ideal situation best context

earn low salaries make more money at work

work long hours spend a lot of time at work

majority most of

occupied time taken up

trapped stuck

overburdened too much work

switch careers change jobs

location place

afford pay for

expenses incumbent on money you have to pay

results in causes

resentful annoyed

projecting putting on to someone else

animosity resentment

significant other partner, husband, wife

firmly established solidly in place

earn decent salaries make a lot of money

savings set aside money saved

devote to put time into

without having to not needing to

making ends meet earning enough money to survive

despite marginal risks regardless of small dangers

concerning related to

overall positive good on the whole

prospective parents possible parents later

putting off childbirth delaying having children

therefore thus

welcomed should be applauded

encouraged motivated

Pronunciation

Practice saying the vocabulary below and use this tip about Google voice search :

ˈgrəʊɪŋ ˈnʌmbəz ˈleɪtər ɪn laɪf faɪˈnænʃəl ədˈvɑːntɪʤɪz trɛnd fɑːr aʊtˈweɪ pəˈsiːvd ˈdaʊnˌsaɪdz sɪgˈnɪfɪkənt treɪd ɒfs ˌɒpəˈtjuːnɪti məˈtjʊərɪti dɪˈsaɪd ˈɜːli ɒn mɪd tuː leɪt 30 ɛs ˈnæʧrəl rɪsk bɪˈfɔː ðæt pɔɪnt ˈtrʌbl kənˈsiːvɪŋ meɪ ɛnd ʌp ˈʧaɪldlɪs ˌpɒsəˈbɪlɪti ədˈvɑːnsɪz fə(ː)ˈtɪlɪti ˈsaɪəns ˈfɜːðəˈmɔː məˈtjʊərɪŋ ɪksˈpɪərɪəns reɪz ə ʧaɪld dɪˈleɪ rɪˈgrɛt ˈəʊpnli ədˈmɪt ˈpeərənthʊd laɪf-ˈɔːltərɪŋ ˈmaɪlstəʊn dɪˈfaɪnɪŋ ˈməʊmənt əˈdʌlthʊd ˌnʌnðəˈlɛs ˈdiːteɪld əˈbʌv peɪl ɪn kəmˈpærɪsn tuː ˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk ˈmɛrɪts dɪˈleɪɪŋ ˈʧaɪldbɜːθ aɪˈdɪəl ˌsɪtjʊˈeɪʃən ɜːn ləʊ ˈsæləriz wɜːk lɒŋ ˈaʊəz məˈʤɒrɪti ˈɒkjʊpaɪd træpt ˌəʊvəˈbɜːdnd swɪʧ kəˈrɪəz ləʊˈkeɪʃən əˈfɔːd ɪksˈpɛnsɪz ɪnˈkʌmbənt ɒn rɪˈzʌlts ɪn rɪˈzɛntfʊl prəˈʤɛktɪŋ ˌænɪˈmɒsɪti sɪgˈnɪfɪkənt ˈʌðə ˈfɜːmli ɪsˈtæblɪʃt ɜːn ˈdiːsnt ˈsæləriz ˈseɪvɪŋz sɛt əˈsaɪd dɪˈvəʊt tuː wɪˈðaʊt ˈhævɪŋ tuː ˈmeɪkɪŋ ɛndz miːt dɪsˈpaɪt ˈmɑːʤɪnəl rɪsks kənˈsɜːnɪŋ ˈəʊvərɔːl ˈpɒzətɪv prəsˈpɛktɪv ˈpeərənts ˈpʊtɪŋ ɒf ˈʧaɪldbɜːθ ˈðeəfɔː ˈwɛlkəmd ɪnˈkʌrɪʤd

Vocabulary Practice

I recommend getting a pencil and piece of paper because that aids memory. Then write down the missing vocabulary from my sample answer in your notebook:

Listening Practice

Learn more about this topic in the video below and practice with these activities :

Reading Practice

Read more about this topic and use these ideas to practice :

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/05/how-people-decide-whether-to-have-children/527520/

Speaking Practice

Practice with the following speaking questions from the real IELTS speaking exam :

Talkative Children

- Do think being talkative is a good quality for children?

- Is it good for children to talk a lot in every situation?

- Why do children talk so much?

- What makes children talk less as the get older sometimes?

- What can teachers do to encourage children to talk more?

Writing Practice

Practice with the same basic topic below and then check with my sample answer:

Parents should take courses in parenting in order to improve the lives of their children.

To what extent do you agree?

IELTS Essay: Parenting

Recommended For You

Latest IELTS Writing Task 1 2024 (Graphs, Charts, Maps, Processes)

by Dave | Sample Answers | 147 Comments

These are the most recent/latest IELTS Writing Task 1 Task topics and questions starting in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and continuing into 2024. ...

Recent IELTS Writing Topics and Questions 2024

by Dave | Sample Answers | 342 Comments

Read here all the newest IELTS questions and topics from 2024 and previous years with sample answers/essays. Be sure to check out my ...

Find my Newest IELTS Post Here – Updated Daily!

by Dave | IELTS FAQ | 18 Comments

IELTS Essay: Celebrities and Charity

by Dave | IELTS Writing Task 2 Real Past Tests Sample Answers | 0 Comment

This is an IELTS writing task 2 sample answer essay that is only available on my Patreon based on a real question from the exam. ...

IELTS Essay: Childhood Obesity

by Dave | EBooks | 0 Comment

IELTS Essay: Competition in University

by Dave | Real Past Tests | 0 Comment

This is an IELTS writing task 2 sample answer essay on the topic of the benefits and disadvantages of competition in university from the real IELTS ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dear Dave, thank you very much for your essays!

May I ask you for advice? In this “advantages/disadvantages” type of essays, is it okay to mention only one advantage and one disadvantage? I find it really hard to mention 2 advantages and 2 disadvantages and fully develop my response with explanations and examples, it’s too lengthy!

Let’s say that in this essay, in the first body paragraph, I only say that there are ”physical challenges” and then I talk about how hard it is to give birth at a later stage. Is saying ”physical challenges” equivalent to saying that there are more than one disadvantage even though technically I only talk about one (which is the risk to human body when giving birth later in life)? Similarly, with the advantages I only talk about ”financial stability” which I can rephrase and call ”economic merits” as you did in your essay.

Is that okay for a body paragraph structure or do we have to mention at least 2 points in each paragraph because the task said ”disadvantageS outweigh advantageS”? [It’s impossible in 40 minutes!]

Thank you very much in advance!

I would not take that risk.

I think it is unfair and agree with you that students will have a tough time developing 4 total ideas. If I would change the test I would, but I can’t and I know there are examiners who will mark you down to a 4/5 for TA because you just develop one advantage or disadvantage (others won’t).

To be on the safe side, have two of each of course the examiner will understand the development will be less.

The way I get around it that you noticed is I have one general main idea and then develop a couple of adv/disadv within that – such as relating to finances. That’s the approach I recommend for students who can do it.

Thank you very much, Dave, for your wise advice! I’ll stay on the safe side and try to practice more with this type of questions. Thank you for your kindness!

You’re welcome!

Dear Dave, could you please look at this sample? Do body paragraphs look a bit choppy and abrupt (because they do to me)? Advantages/Disadvantages essays are incredibly difficult for me as the balance between ”too general” and ”too detailed” isn’t clear at times. Did I develop my ideas fully? I typed this essay in 30 minutes (in paper version I will need more time, that’s why I saved 10 extra minutes).

It is increasingly common these days to have children later in life. While there are some disadvantages associated with physical challenges, I believe that advantages far outweigh drawbacks.

The majority of trade-offs relate to physical issues concerned with raising a child. First, giving birth to the child is a hazardous act, when undertaken at a later stage in life. The mortality rate among aging parents, for instance, was much lower in the past, when children were born to families as early as possible. This, however, can still be prevented with the development of modern medicine. Second, raising a child may be considered physically demanding since kids require attention, and one has to be fit and strong to meet the child’s needs. Activities, such as playing games, escorting the kid to a kindergarten, or attending a doctor’s office demand a certain level of physical effort.

Nevertheless, there are still advantages associated with parents’ financial stability and maturity. First, older parents are more firmly established in their careers and, therefore, find it easier to cover all the necessary expenses. These might range from quite mediocre, such as clothing and nutrition, to more elaborate ones, including tuition fees and accommodation. Second, mature parents are more experienced and possess greater wisdom about life so that they can assist the children in the process of growing up. Their children might find it useful to get advice regarding life-altering choices, such as choosing a partner, or deciding on their career.

In conclusion, although there are certain setbacks associated with later childbirth, they can still be overcome by the use of science and medicine. Therefore, advantages detailed above can justifiably outweigh the drawbacks.

I think you are striking a really good balance in your writing and should keep doing what you are doing.

Most students who write 2 ideas in a paragraph, don’t develop one of them but you develop them fully and the detailing is very specific.

Keep it up – don’t change the way you are writing!

Dear Dave, thank you sooooo much! I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that, you really saved my life!

No problem – best of luck on your exam!

Exclusive Ebooks, PDFs and more from me!

Sign up for patreon.

Don't miss out!

"The highest quality materials anywhere on the internet! Dave improved my writing and vocabulary so much. Really affordable options you don't want to miss out on!"

Minh, Vietnam

Hi, I’m Dave! Welcome to my IELTS exclusive resources! Before you commit I want to explain very clearly why there’s no one better to help you learn about IELTS and improve your English at the same time... Read more

Patreon Exclusive Ebooks Available Now!

Essays on Childbirth

Faq about childbirth.

Hektoen International

A Journal of Medical Humanities

Changes in childbirth in the United States: 1750–1950

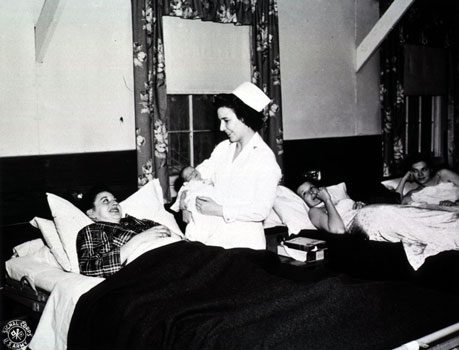

Laura Kaplan New York, New York, United States

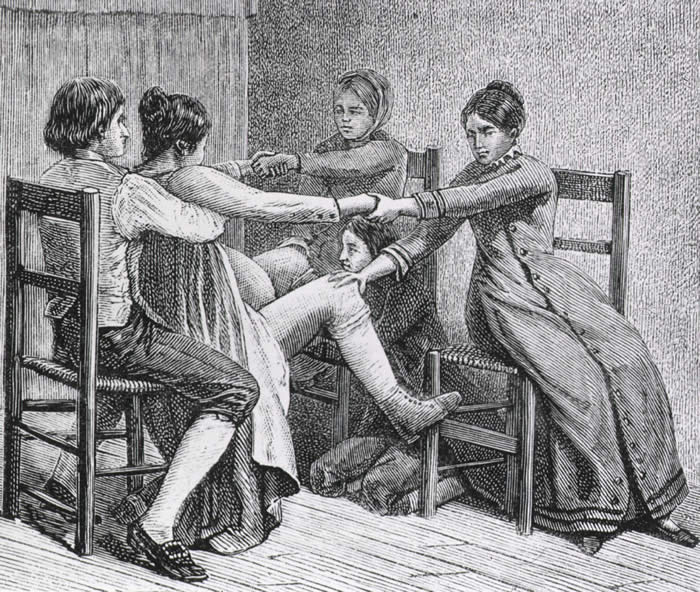

Gustave Joseph Witkowski Wood print From Histoire des accouchements chez tous les peuples

For most of American history, pregnancy, labor and delivery, and post-partum have been dangerous periods for mother and child. However, starting slowly in the late 18 th century and accelerating into the late 19 th century, labor and delivery radically changed. Initially new medical interventions, such as forceps and anesthesia, caused as many issues as they seemed to resolve as they emerged in burgeoning medical school obstetric programs. But the introduction of standard physician training accompanied by an emphasis on infection control eventually led to substantially decreased morbidity and mortality in the mid-20 th century. From a home-based event managed by female midwives and other birth attendants without formal training to a hospital-based, standardized encounter managed by formally trained male and female physicians and other healthcare practitioners, this complete paradigm shift resulted from women’s determination to have a safe and painless delivery, a new scientific foundation, innovations in medicine, and changes in the social landscape. (Fig 1)

Until the 20 th century, the majority of US births occurred in the home, attended by female midwives and numerous female family and friends. As no formal training programs, curricula, licensing processes, or other official standards for birth attendants existed until the 18 th century, women learned to help and support their loved ones through their own and others’ birth experiences. Historically, midwives—a diverse group of female community members who were usually married with children of their own—learned their skills by delivering their neighbors’ children or through loose apprenticeships with more established midwives. Only after the 1860s did some midwives begin attending midwifery schools. Midwives tended to intervene as minimally as possible and worked to assist labor along its natural course. Yet childbirth and the postpartum period long remained times of high morbidity and mortality. 1,2

As American women in the 18 th and 19 th centuries had on average seven live births during their lifetimes—and potentially a number of undocumented early terminations—women’s diaries and letters reveal the considerable time women spent preparing for the pain and the realistic possibility of dying in childbirth. One 19 th century woman wrote to her family late in her pregnancy: “If I live and regain my health, I will surely write to [all the people to whom she owed letters].” 1 In 1885, another wrote about her third birth, “Between oceans of pain, there stretched continents of fear; fear of death and a dread of suffering beyond bearing.” 1 In addition, women who survived childbirth and the postpartum period frequently suffered from lifelong morbidities, such as vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas from unrepaired lacerations. The resulting lifelong incontinence and vaginal, cervical, and perineal prolapses of these fistulas caused painful sexual intercourse and difficulties with future pregnancies. A physician noted in 1897, “the wide-spread mutilation . . . is so common, indeed, that we scarcely find a normal perineum after childbirth.” 1 Despite numerous uncertainties inherent in childbearing into the 20 th century, American women persevered to control the process through the selection of childbirth attendants, preferring to deliver in a comfortable, safe setting (sometimes traveling back to their childhood home). 1

American women first invited male physicians to assist in birthing rooms in the 1760s. 1 Previously, physicians, who were exclusively male, were rarely called except in extreme emergencies, and men were excluded from attendance unless women were unavailable. In 1762, Dr. William Shippen, Jr. of Philadelphia, after training in midwifery in London and Edinburgh, became the first American male physician to establish a normal obstetrics practice in the US. Shippen also pioneered formal midwifery education through a lecture series initially taught to both male physicians and female midwives, but later limited to male physicians. Other physicians subsequently offered courses in other large American cities, and medical schools progressively incorporated obstetric education into their curricula.

As numbers of physicians formally trained in midwifery increased through the 19 th century, the wealthy, urban elite—who perceived male physicians as superior in education and training—were progressively more inclined to pay the higher physician fees, presuming that the physician’s modern interventions would result in safer childbirth. Such women chose their physician attendants similarly to how they had chosen their midwife attendants. For instance, at the turn of the century, records showed that midwife birth attendants in both rural and urban Wisconsin primarily attended the labor of local women of similar ethnic backgrounds. For deliveries, city midwives in Milwaukee and Madison rarely traveled beyond wards contiguous to their own, and rural midwives rarely worked outside their township. 2 Similarly, physicians tended to be from their immediate communities and of similar ethnic backgrounds. Even with the rise of railroad lines and automobiles in the 20 th century, physicians’ practice areas did not significantly expand. 2

New medical interventions that physicians employed—such as forceps, anesthesia, and laceration repair—increased the popular perception of the increased safety being provided in childbirth. 1,3 In the early 19 th century, the physicians’ primary interventions were forceps for difficult deliveries, bloodletting to relieve pain and accelerate labor, ergot to stimulate contractions, and drugs (particularly opium) for pain relief. 1 The forceps were invented in the 1590s by Peter Chamberlen the Elder, a French Huguenot “male midwife” whose family had fled to England. Peter was one of the most famous male midwives in England, serving as the queen’s surgeon and delivering the children of multiple kings. He and his family kept the forceps as a family secret for over a century, reportedly performing deliveries under a sheet or blanket to guard their creation.

In the early 18 th century, other practitioners developed their own versions of forceps, Dr. William Smellie of Scotland being the most well-known. Smellie taught midwifery and systemically described the proper use of forceps, publishing Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery in 1752. 1,3 With the introduction of forceps, physicians were able to extract fetuses that had previously been undeliverable, which mothers viewed as miraculous. However, as no standards existed for when forceps should be employed, 19 th century physicians were generally improperly trained in their use. As a result, individual practices differed substantially, and interventions frequently caused new problems. Some physicians used forceps routinely in every delivery even though their misapplication resulted in increased perineal lacerations, uterine trauma, and fetal defects. There was great debate among American physicians about the proper use and abuse of forceps throughout the 19 th century. 1

The introduction of anesthesia in the mid-19 th century was a key milestone in the history of obstetrics. Based on reading of thousands of diaries and letters from parturient American women from the 18 th and 19 th centuries, Judith Walzer Leavitt concluded that “next to the fear of death, pain was probably the single part of birth most hated by birthing women.” 1 After the first public demonstration of ether in 1846 by dentist William Morton at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, 4 Fanny Appleton Longfellow was the first woman to use it during childbirth in 1847, writing, “I feel proud to be the pioneer for less suffering for poor, weak womankind. This is certainly the greatest blessing of this age.” 1 Subsequently, wealthy women pressed physicians to use ether and chloroform to decrease their suffering. As with forceps, proper use of anesthesia was not standardized, and practice and debate varied tremendously about all aspects of its use, including when and whether to initiate it and appropriate dosing. Consequently, improper anesthetic use caused numerous complications, particularly prolonged labor due to decreased ability of the uterus to contract, newborn breathing difficulty, and hemorrhage. 1

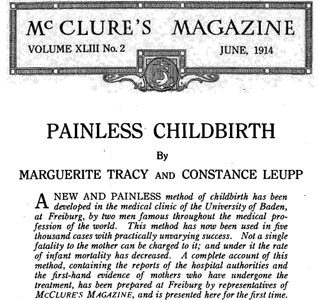

Due to the limitations of ether and chloroform, women and their physicians searched for a superior anesthetic. 5 In the early 20 th century, Austrian and German physicians—followed by American physicians a few years later—began experimenting with a combination of scopolamine and morphine in childbirth. Alone, scopolamine acts an as amnesic, erasing all later memory of childbirth. Given with an opiate, it also has an anesthetic effect. Scopolamine-morphine, named “twilight sleep,” permitted the patient to be semiconscious with intact contractions during labor, allowing the physician to coach the woman through childbirth without her remembering the experience afterwards. In 1914, McClure’s magazine published “Painless Childbirth,” in which two laywomen raved about German Drs. Karl Gauss and Bernhardt Kronig’s twilight sleep protocol, but lamented the American physician’s inadequate training in the method.

Immediately, a vocal contingent of American women embraced and advocated for twilight sleep for their deliveries, and numerous articles and books were published on the subject. 5 From 1914–1915, the National Twilight Sleep Association—organized by wealthy upper- and middle-class women and led by prominent leaders such as Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen in Chicago and Mrs. Francis X. Carmody—advocated relentlessly for physicians and women to adopt twilight sleep, which allowed painless childbirth. In the words of Mrs. Carmody: “the twilight sleep is wonderful but, if you women want it you will have to fight for it, for the mass of doctors are opposed to it.” 5 As with other innovations, twilight sleep suffered from widespread controversy over in the medical community and enormous discrepancy in practice. Despite the drug’s amnesic effects, women under scopolamine still experienced intense labor pains, screaming and thrashing so much during labor that they were placed in “crib beds” to avoid accidents. 1

By the summer of 1915, twilight sleep sharply declined in popularity. Inappropriate use of the drug by physicians had frequently led to adverse events, including maternal delirium and asphyxiation of newborns. Notably, in August 1915, Mrs. Carmody died in childbirth while under scopolamine’s influence. Her physicians and husband maintained that her death did not result from scopolamine use; however, her neighbor Mrs. Alice J. Olsen initiated a campaign against twilight sleep in response to the event. As the drug’s popularity decreased, doctors limited scopolamine use to the first stage of labor, when it was still considered safe. 5

Though the twilight sleep movement was brief, it had long-lasting repercussions. The drug’s promise of a painless childbirth propelled women and their physicians to increasingly seek drugs and other means to ensure that childbirth would be as painless as possible. 1 This pursuit, in the context of the twilight sleep movement, brought many women—who otherwise would have chosen home deliveries—to the hospital to avoid numerous problems with home scopolamine administration.

As infection was one of the leading causes of postpartum death, infection control also attracted women to physician-attended labor in hospitals. 1 However, while American Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes and Austrian Dr. Ignnaz Semmelweis recommended careful handwashing to prevent doctor-to-patient transmission of infection in the 1840s, it was Koch, Pasteur, and others’ revolutionary work on bacteria in the late 1860s that propelled the infection control movement in labor and delivery. By the 1880s, increasing numbers of physicians adopted infection control methods, though debates on the matter persisted for decades.

Early methods of antisepsis included vaginal chloral douches (injections of antiseptics into the vagina before and after delivery) and strict scrubbing of the genital area and physician’s hands (with numerous specific recipes and protocols). By the turn of the century, rubber gloves, a rubber “Kelly pad” (a rubber sheet placed under the patient for discharges), and shaving of the genital area were standard recommendations for practicing physicians. Initially, physicians tried to incorporate antisepsis as much as possible in home birthing rooms. However, in the first decades of the 20 th century, they began to encourage patients to come to hospitals for truly sterile births, as it was difficult to guarantee the cleanliness of the patient’s home and adherence of other birth attendants to their practices. 1

Other non-medical developments led to changes in women’s childbirth practices in the US, including the “mystification of medical knowledge” and the breakdown in women’s social networks for childbirth. With advances in obstetrics, women believed the promise of “science” could alleviate dangers and fears surrounding childbirth. Early 20 th century women’s journals and American women advised each other to select a trustworthy physician and follow his guidance, as he knew best. In addition, with increased mobility and urbanization in the 19 th and 20 th centuries, women no longer had the same expanded social support for pregnancy. The idea of a hospital where nurses and physicians took care of all of their needs was very appealing. 1

Hospital deliveries through the 1940s were entirely different from home deliveries, however. At home, the parturient exerted control over procedures and anesthesia administered by birthing attendants; in the hospital, women had no input into the drugs and procedures they received. Through the 1940s, hospital births frequently left women disillusioned and terrified, often contributing to psychiatric distress for extended periods after delivery. One woman wrote: “Months later I would scream out loud and wake up remembering that lonely labor room and just feeling no one cared what happened to me, no one kind reassuring word was spoken by nurse or doctor. I was treated as if I was an inanimate object.” 1

Interestingly, despite their promise, the numerous advances in obstetric medicine in the 19 th and first decades of the 20 th centuries did not immediately translate to improved safety during labor and the postpartum period. 1,2 Though hospital births were believed to be safer, there was no decrease in maternal mortality between hospital and home births until the 1940s. Despite strides in obstetric knowledge, practical training in medical school remained limited in the first decades of the 20 th century. Faculty lectures, student recitations, and practice with a manikin largely comprised the obstetric curriculum at most medical schools. While some schools had courses devoted to pelvic exams and delivery with and without obstetric instruments using a manikin, until 1900, the majority of medical students observed at most one to two deliveries in either the lecture hall or the patient’s home—and many never witnessed one. Famous obstetrician Dr. Joseph DeLee, who graduated from Northwestern, later recalled that he felt lucky to have observed two deliveries as a medical student.

The publications of the 1910 Flexner Report and Dr. J. Whitridge Williams of Johns Hopkins’s 1914 survey of American medical schools’ obstetrics departments both showcased medical schools’ failures in obstetric education. As a result, medical schools labored to increase the number of births witnessed by medical students. 1 For decades, this was an uphill battle. Consequently, new physicians continued to be poorly trained to handle deliveries, and practicing physicians still lacked standards of practice to ensure the safety of delivery interventions. 2 Lacking such standards, physicians during this period routinely over-utilized forceps, drugs to accelerate delivery, episiotomies, and other interventions—despite ongoing debate in the medical literature—in order to distinguish themselves from low-interventionalist midwives. Through the 1920s, mortality rates for midwife- and physician-assisted births remained similar, with physician assisted delivery possibly faring worse.

In the 1930s and 40s, American physicians—largely wealthy, native-born, white males—increasingly differentiated themselves from traditional midwives—chiefly working-class immigrants and African Americans—through standardized medical school curricula, formal credentials for practice, and professional societies with the authority for self-regulation. 1 In addition obstetric specialists also endeavored to establish obstetrics as its own hospital-based specialty, arguing that poorly trained general practitioners, who were “responsible for many obstetrical disasters” needed to cease obstetric work. In addition to establishing obstetrics’ role in the hospital, obstetric specialists redefined the medical philosophy of birth. Contrary to previous depictions of birth as a natural, though painful and dangerous, process, the new obstetricians, such as Dr. Joseph DeLee, deemed birth a “pathologic process” that required close medical supervision. Obstetric specialists formed professional associations, such as the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 1930. By 1936, ACOG was certifying specialists, with the authority to determine who could establish a hospital-based practice.

From the turn of the century on, women increasingly opted to deliver with physicians over midwives—initially with familiar community doctors and then with hospital-based physicians. In 1900, midwives still delivered half of all US births, but by 1930, this number dropped to less than 15% of US births, primarily in the South. 2 Similarly, in 1900, less than 10% of American births occurred in a hospital. By 1940, 26.7% of non-white and 55% of white American births took place in a hospital, increasing to 56% (non-white) and 88% (white) by 1950. 1 It was at the turn of the century, when births became more prevalent in the hospital, that physician-assisted birth no longer became the purview of the wealthy; very poor and/or single women who lacked other alternatives also utilized physicians as birth attendants. 1

During this period, physicians and hospitals learned to standardize obstetric practices to reduce mortality, such as appropriate use of drugs, proper indications and contraindications for obstetric procedures, and improved methods of antisepsis. Later developments of antibiotics, blood transfusions for hemorrhages, and prenatal care for high risk patients significantly contributed to the decline in maternal mortality. As maternal mortality rates fell in the 1940s and 1950s, women sought to regain some control, decision-making power, and humanity in the birth process that they had for millennia prior to the move to the hospital. In this environment, the natural childbirth movement and other philosophies of childbirth as a natural, normal process in which women possess control developed beginning in the 1950s–60s. 1

Birth in America changed dramatically from the colonial period to the 20 th century. The development of obstetrical “science” and numerous innovations including forceps, anesthesia, and antisepsis transformed childbirth into a standardized process that women no longer feared. Originally occurring at home in a familiar bed supported by female midwives, family, and friends, childbirth moved to a sterile hospital environment accompanied by male and female health professionals and select loved ones. By the middle of the 20 th century, these changes coincided with significant reductions in morbidity and mortality as a result of childbirth. By actively seeking safer and less painful childbirth and slowly allowing physicians and their developing technology to attend to them, parturient women changed the natural history and their personal experiences of childbirth.

- Judith Walzer Leavitt, Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America 1750–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Charlotte G. Borst, Catching Babies: The Professionalization of Childbirth (1870–1920) (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- J. Drife, “The Start of Life: A History of Obstetrics,” Postgraduate Medical Journal 78 (2002): 311–315, http://pmj.bmj.com/content/78/919/311.full.

- James F. Crenshaw and Elizabeth A. M. Frost, “The Discovery of Ether Anesthesia: Jumping on the 19th-century Bandwagon,” Archives of Family Medicine 2 (May 1993): 481–484.

- Amy Hairston, “The Debate Over Twilight Sleep: Women Influencing Their Medicine,” Journal of Women’s Health 5, no. 5 (1996), http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/jwh.1996.5.489.

LAURA KAPLAN , MD, studied the history of science, medicine, and technology as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University and wrote this paper as a fourth-year medical student in Dr. Mindy Schwartz’s History of Medicine course at the University of Chicago. She is now a Family Medicine resident at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 4

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Open access

- Published: 03 November 2018

Childbirth experiences and their derived meaning: a qualitative study among postnatal mothers in Mbale regional referral hospital, Uganda

- Josephine Namujju ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3408-9560 1 ,

- Richard Muhindo 1 ,

- Lilian T. Mselle 2 ,

- Peter Waiswa 3 , 4 ,

- Joyce Nankumbi 1 &

- Patience Muwanguzi 1

Reproductive Health volume 15 , Article number: 183 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

32 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Evidence shows that negative childbirth experiences may lead to undesirable effects including failure to breastfeed, reduced love for the baby, emotional upsets, post-traumatic disorders and depression among mothers. Understanding childbirth experiences and their meaning could be important in planning individualized care for mothers. The purpose of this study was to explore childbirth experiences and their meaning among postnatal mothers.

A phenomenological qualitative study was conducted at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital among 25 postnatal mothers within two months after birth using semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions and data was thematically analyzed.

The severity, duration and patterns of labour pains were a major concern by almost all women. Women had divergent feelings of yes and no need of biomedical pain relief administration during childbirth. Mothers were socially orientated to regard labour pains as a normal phenomenon regardless of their nature. The health providers’ attitudes, care and support gave positive and negative birth experiences. The Physical and psychosocial support provided comfort, consolation and encouragement to the mothers while inappropriate care, poor communication and compromised privacy contributed to the mothers’ negative childbirth experiences. The type of birth affected the interpretations of the birth experiences. Women who gave birth vaginally, thought they were strong and brave, determined and self-confident; and were respected by members of their communities. On the contrary, the women who gave birth by operation were culturally considered bewitched, weak and failures.

Childbirth experiences were unique; elicited unique feelings, responses and challenges to individual mothers. The findings may be useful in designing interventions that focus on individualized care to meet individual needs and expectations of mothers during childbirth.

Peer Review reports

Plain ENGLISH summary

Childbirth experiences are the women’s personal feelings and interpretations of birth processes. Birth experiences to some women have meant hard work, exciting lovely event and to others it is a stressful, exhausting and unpredictable experience. Negative experiences have been associated with poor support and care, fear, excessive pain, discomfort and undesirable outcomes. Participating in making decisions regarding childbirth care and being supported by healthcare providers gives a positive memory and increases the woman’s confidence and love for the baby and better adjustment to motherhood. Understanding the women’s childbirth experiences and their meaning is important in providing socially acceptable individualized care during and after birth. In Uganda, few studies on childbirth experiences of mothers and their meanings have been done. This study explored childbirth experiences and their meanings among women within two months after giving birth. Twelve women were interviewed one on one and thirteen women in two groups of seven and six in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, in the Eastern part of Uganda. The women reported unique experiences of labour pains, they had social orientation on labour and gave different views on pain management during birth. Negative and positive attitudes and care by service providers were described and the social support from the significant others was noted as a source of comfort and encouragement. The personal women’s and society’s interpretations of birth experiences focused on the type of birth undergone. The vaginal birth meant braveness to some mothers and caesarean birth was associated with witchcraft and weakness of a woman. In conclusion, the individual mothers had unique childbirth experiences that required service provider’s understanding and personalized care.

Childbirth is a significant event in a woman’s life and a transition to motherhood. Childbirth experiences are the subjective psychological and physiological processes, influenced by the social and environmental factors [ 1 ]. Birth experiences elicit uncertainties of the next destination with feelings of inabilities [ 2 ]. Labour pain has been regarded as a “well kept – secret” whose true reality cannot be explained until you go through it causing fear and emotional upsets [ 3 ]. Childbirth is perceived as a paradox of moments of sadness and disappointment initially and joy crowns its end if a baby is alive [ 3 ]. The interpretations of birth experiences further include hard work, exciting intimate event and a stressful, exhausting and unpredictable phenomenon [ 4 ]. To some women, giving birth is life itself, a fulfillment of God’s plan and the law of procreation and a turning point between death and life for the woman and her baby [ 5 ].

Childbirth experiences could be both positive and negative. Negative experiences are characterized by fear, excessive pain, poor support and care, discomfort and undesirable outcomes [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The negative experiences of medical interventions like epidural analgesia, induction of labor and instrumental vaginal delivery have been found to be associated with post-traumatic stress, fear of childbirth, reduced child care and emotional upsets among women [ 7 , 9 ]. The positive memories of being in control over the situational happenings and the decisions on care coupled with the healthcare providers’ support are said to enhance self-confidence with feelings of accomplishment and better adjustment to motherhood [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The positive birth experiences are thus said to improve the bonding between the mother and the baby [ 12 , 13 , 14 ].

Understanding the women’s childbirth experiences and their meaning is crucial in the provision of individualized and culturally sensitive care during and after childbirth [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A number of studies have described women’s childbirth experiences and their meaning but these studies were done in the developed world. In Uganda, studies on childbirth experiences of mothers and the perceived meanings are scarce. This study therefore, describes the childbirth experiences and the perceived meanings among postnatal mothers seeking postnatal services at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital in Eastern Uganda to broaden the information base for appropriate intervention development and individualized care during childbirth.

Study design and setting

A phenomenological qualitative research design was used. Phenomenological qualitative research is an approach that describes life experiences and gives them meaning [ 18 ]. The design allows exploration of participants’ experiences, perspectives and feelings, in depth, through a holistic framework. Childbirth is a lived experience to women whose truth and reality is deeply embedded in the lives of those that have experienced it [ 19 , 20 ]. In this study, it was specifically used to explore experiences, feelings and perspectives of women who had given birth. The study was conducted at Mbale Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) located in Mbale Municipality, Northeast of Kampala, Uganda. MRRH is a public hospital with 500 bed capacity. The hospital serves 13 districts (with about 4 million people in the region) and about 800 women give birth per month in this hospital. Specifically, the study was carried out at the Young Child Clinic (YCC), one of the clinics run by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in MRRH. The clinic had four certified health care providers including 3 midwives and 1 public health nurse. It offers immunization, health education, monitoring growth and development to children under 5 years; postnatal care services, HIV counseling and testing, and referral services for example HIV positive mothers and babies were being referred to the HIV clinic for care. On average, 35 mothers and babies were attended to at this clinic per day.

Participants and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants. Purposive sampling allows a researcher to get rich information to a particular research question [ 21 ]. The researcher oriented the staff of the YCC on the study and worked with the midwife in charge of the clinic to identify potential participants. The inclusion criteria were the postnatal mothers who gave birth within two months with live babies and those that were able to communicate in English, Luganda or Lumasaba. Luganda however, which all participants understood and spoke fluently was preferred in the two discussions. After receiving the services they had come for, all the potential participants were requested to meet with the researcher. She explained to them the study, its aim and how it was going to be conducted including their rights and the principles of confidentiality. Those who agreed to take part in the study gave written consent and a suitable place (with privacy) at hospital was arranged for an interview or discussion.

Data collection

To build the credibility and better understanding of the childbirth experiences two methods of data collection were used; the semi-structured interviews (SSI) and the focus group discussions (FGDs).

Semi-structured interviews

Twelve (12) semi-structured interviews with postnatal mothers were conducted in Luganda and English by the first author at YCC in a quiet room adjacent to the clinic. The saturation was reached with 12 interviews where the answers from mothers seemed to repeat information gained earlier with little new information [ 22 ] . A semi-structured interview guide with open ended questions and probes were used to explore and understand better the issues as they emerged [ 23 ] and elicited broader and deeper views from participants. All the interviews were audio recorded and lasted within 30 min.

Focus group discussions

Two FGDs with postnatal mothers were conducted. The discussion groups included 6 and 7 postnatal mothers. The first author moderated the discussions and notes and non-verbal clues were taken by the assistant, the clinic midwife who was not involved during the participants’ recruitment process. The FGD guide used centered on the mothers’ childbirth experiences and their meanings. The discussions were held in Luganda, the local language of instruction in schools, spoken and preferred by all participants and all the discussions were audio recorded with permission from participants. The discussions lasted between 60 and 80 min.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis guided the analysis of data. All the audio recorded interviews and discussions were transcribed verbatim and were translated from Luganda to English. The English translated transcripts were reviewed and edited to ensure correct interpretation of the mothers’ accounts. The analysis procedure included familiarization with the material through careful reading of sentence by sentence for many times, identification of the codes, searching for subcategories, formulation, revision and interpretation of themes. Phrases and sentences related to the mothers’ experiences of childbirth were coded in the margin of the transcript sheets. The coding was predominantly close to the text using mothers’ own descriptions. The codes with similar content were then brought together into sub-categories and themes. The authors discussed and reflected on the interpretations of the mothers’ descriptions of their childbirth experiences and agreed on the themes. Anonymous quotes were used to illustrate the facts.

Methodological considerations

Qualitative researchers suggest the use of credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability as methods to ensure trustworthiness in qualitative studies [ 24 , 25 ]. The researcher ensured credibility through use of multiple data collection methods (focus group discussions and in depth-interviews) which allowed triangulation of findings. Also the researcher established good rapport through having prolonged engagement in the field, used Luganda language (during FGDs) to build trust with participants. Bracketing was done through the researcher’s honest self-examination of the values, beliefs, interests and prior experiences. These were noted down and kept at the back of the mind right from proposal development through data collection, analysis and report writing to ensure that the findings were the views of the participants and not the researcher’s imaginations.Dependability and conformability were promoted through inquiry audit where by the researchers reviewed and examined the research process and the data analysis in order to ensure that the findings were consistent. Further, the thick description of the phenomenon under study, the purposive sampling used, the data collection methods that were employed and using participant’s own words during analysis and write up enhance the understanding of childbirth experiences and will allow for others to determine its transferability to other contexts [ 26 ] .

The 25 women who were interviewed about their childbirth experiences described themselves as housewives ( n = 7), teachers ( n = 6), business women (n = 6), students ( n = 2), a journalist, an administrator, a peasant and health information assistant ( n = 1). They were between 18 and 33 years of age, 88% ( n = 22) were married; 88% (n = 22)gave birth in the health facilities and 12% delivered at their homes or from the traditional birth attendant. Their parity ranged from one to five and the majority were Christians (Born again (32%), Protestants (24%), Catholics (12%), the rest were Moslems (32%).

From the 12 semi-structured interviews and 2 focus group discussions, five (5) themes emerged. These included the Childbirth experiences (Labour pains and management, Institutional care and support, Childbirth fears and Social support) and the Meaning attached to childbirth experiences (Individual and Cultural interpretations). The Women reported diverse trends in their birth experiences that provided the differences and the basis for emphasis. Numbers were used to identify participants during group discussions instead of names for privacy purposes and fictive names are used in the presentation of quotes.

Childbirth experiences

Labour pains and management.

The memory of labour pains remained in the minds of almost all women and formed the basis for their stories. The women’s birth pain experiences were viewed and expressed in terms of intensity, duration and patterns. The severe labour pains to some women were characterized by the temporary moments of confusion and loss of understanding as one mother expressed:

This is the 4 th born, other children never pained me like this one,…contractions were very strong and I reached a point when I did not understand well, they just lifted me up on to the bed. ….I just found myself delivered. After delivering, my senses came back (Zaifa, 27 years, a mother of 4)

Rose who experienced abnormal labour patterns also said:

Labour for my last born was hard, because the pains were much and later the contractions stopped. …..later the midwives put on a drip for contractions (Rose, 30 years, a mother of 4).

Some womenexperienced labour for a long duration and its effects were reported with dismay, frustration and loss of hope as one mother explained:

…the contractions pained me for 3 days… I went back, they examined me … I was still not ready. I walked and walked …. I went back at 6.00pm (second day, I was still not ready. I went back at 10.00 p.m, they told me I was not ready. I went back at midnight, the midwife told me, aaaah we are fed up with you, you go and walk so that the baby can move down, …the body was feeling like a metal, I said this time I am dead ( Eseza, 23years, a mother of one) .

The labour pain aspect of childbirth is one dimension that is given attention in various ways. In this study, the women were socially oriented to view labour pains as a normal phenomenon regardless of intensity, duration and varying patterns. This psychological care in preparation for birth provided consolation, hope and encouragement as narratives below indicate:

“ My attendants told me, contractions pain but you must be strong, and when time comes for the baby to come out, the baby itself will force you ” (Shifa, a 28 year old mother of 2).

“Getting much pain happens and is human and normal to a woman, but it is God who gives you the life and energy” (Rehema, a 33 year old mother of five) .

Labour pain management elicited mixed feelings from participants. Some women believed childbirth is natural and therefore should be left to take the natural course, while others felt it was necessary to reduce on the birth pains through medication if it was possible. According to the women’s descriptions, none of them received biomedical painkillers during birth and one mother explained:

Next time I deliver, I would not want to have too much labour pains like the ones I went through. If that medicine was there, I would feel like having such a drug to reduce the pain (Christine, 25 years, a first time mother).

Some women doubted as to whether medicine could have an effect on a natural process like labour pains as they had no prior knowledge to the intervention

“I think no need of medicine, because it is natural. I think even if they give you some medicine for pain, contractions would still come because the baby has to come out. I think the drugs cannot reduce those pains…every other woman goes through that” (Irene, 26 years, a primepara) .

Institutional care and support

The experiences of women regarding care and support received in the health facilities varied from positive by some mothers to negative and non-satisfying by others. Regarding institutional births, majority of women had given birth from the Regional Referral Hospital apart from one woman who had delivered from a private maternity centre. The women’s comments generally centred on the attitude of service providers, the interpersonal communication, the physical and psychological support and how the labour complications were managed. For those who felt good about their labour experiences described them in form of the good reception and attention given to them, the physical and psychological support through counseling; being listened to and having been given appropriate management to the complications as some mothers narrated:

The midwives were good…. even when they were attending to other people, when I would also call her (musawo) meaning a health care provider, also come and help me, She would not shout at me, would say let me come, I am hearing. I used to hear that they shout at people but for me they never shouted at me. ( Christine, a 25 year old mother of one).

Another one said:

The midwives welcomed me well, examined me … delivery time had not reached. I told them, basawo, I am sick, (HIV positive) they said you have done a good thing to tell us…, they said don’t fear. Some hide and do not tell us. ….when the time reaches you will push well and in case something wrong happens, we will help you. When time came, the midwife helped me to climb the bed. After delivery, I bled a lot … quickly they ran and gave me an injection and blood stopped. … weighed the baby, wrote treatment and gave the syrup for the baby ( Rehema, a 33year mother of 5 ).

As some mothers expressed their birth experiences with confidence and trust in service providers, to others it was a moment of reflection on the sadness, suffering and agony they went through. The women described experiences of non- caring attitude, limited technical care and support; quarreling and being rough to them. Rose,one of the mothers that was cared for by the morning and evening ward staff described her experience with the midwife of the 2nd shift:

…. I called her that I feel like something pushing me, she never bothered. She said, “Keep quiet, for you, you are making yourself tired for nothing, you are not going to deliver now”. I forced to deliver myself, what can I do? (Voice tone lowered) I said that if I relax I would lose my baby…. When the midwife reached, the baby was out and a lot of water (liquor) had poured on the baby. She (midwife) got annoyed, quarreled…. She cut the baby’s cord from that water yet I normally see midwives cut the cord from the mother’s abdomen. I felt too bad.

The practices reflected by some health care providers were unethical and violated the rights of the clients as one mother who was slapped during the time she pushed her baby narrated:

… the midwife told me to push. I tried to push and push, she was even slapping me telling me to push. The old woman (attendant) had given the midwife some money, now she was on my “bamper” (on my neck). “I have told you to push the baby with slaps” (Ruth, a 20 year old mother of 2)

Giving birth by caesarean was a hurdle. One mother who was taken to the theatre for the caesarean birth experienced delay to be operated as theatre was unready causing her stress and anxiety. This was heighted by being left exposed naked, a factor that compromised her privacy as she lamented:

….now you are under stress and you feel like… they have to do it (operation) immediately. “They take you in the theatre room, you again spend some good time there when they are still organizing. It was too bad, ….now even you feel stress is coming back again , you try to console yourself , you control…As you wait, you are naked, you are exposed there… (laughed while shaking her head)… you know how funny it is. ..you are nude. It was not good, privacy was not enough”. (Caroline, a 30 year old mother of 3 children).

Many women were giving birth for the first time and as such needed more information regarding labour and its proceedings. Women noted limited effective communication and sharing of information by the service providers. The non-involvement of a mother in decision-making regarding her care resulted in a number of unanswered questions as one woman explained:

….. the doctor told me, Irene, with you, you are just going for an operation. …I had to break down… because I was like what has gone wrong? ... why not me to deliver like other women? ….they are telling me I am going for an operation but they are not telling me the cause! Doctor Just told me, the baby was big. He then used some medical language that I did not understand. She did not convince me as to why I should have an operation… they were talking alone! (Irene, a first time mother).

Social support

The mothers according to their narratives appreciated the presence, proximity, the physical and psychological support from their birth companions that were basically family members (the mums, sisters, mothers-in law, aunties, husbands) and friends. Physically, the women were supported by giving them food and drinks like tea, they were supported to walk around before reaching second stage of labour and their backs were rubbed to provide relief during contractions by their birth companions.

Eseza a 23 year old mother of 3 recounted:

Attendants (birth companions ) helped me to get tea to drink, they kept around, and during that time when I could get the contractions, they could support me at the back, rub it, I could get some relief of about one minute.

Irene, a 26 year old primepara, who was supported through counselling by a relative before a caesarean birth recalled:

“At that time when I broke down,… my sister in law and mother in law were there for me. They tried to counsel and consoled me but still it wasn’t an easy moment”

The male partners were involved in intrapartum care of their spouses at different times and in various ways. Although their (male partners’) physical presence was registered at the hospital, their participation in real care was minimal. One mother whose husband was in hospital but at a distance from the maternity unit commented:

My husband was not near, had feared and moved away. I never wanted him to be near because when you are in labour the face changes, you may say that it is this one who brought the problems and get annoyed with him (laughed) (Shifa, a mother of 2).

Another mother whose husband fully participated in the processes of the birth of their baby by being present at the side of his partner and providing physical and psychological support during the pushing time gave her story:

When I came back to the labour ward they told me “the baby has reached you push”, I was not feeling any energy. ….my husband helped me, held me and he never feared. When the baby was coming out, he told me that “bambi” (meaning my friend) push more,the head is coming, add in more effort. … I felt good, I liked it so much because he gave me support,and he was there (Faith, a mother of one).

Childbirth fears

Childbirth is a moment of unpredictable “next” in terms of the outcome of the baby and mother both to those who give birth normally and by caesarean birth. In this study, these experiences were worsened by giving birth by a caesarean resulting into mothers’ fear, anxiety and loss of hope for survival as one woman recalled:

It is hard when you are going for a cesarean birth, you are always worried. …… you are not sure of what is going to happen there….. in such situation the mother is not sure of the baby’s survival and her own wellbeing; or she might come out with complications. Yah…it is like you are going for trouble when you are seeing (mother laughed) ( Catherine, a 30-year mother of 3, with 3 previous scars) .

The situation can be more terrifying to those who are giving birth for the first time. Irene, a first time mother had refused a caesarean birth for fear of losing her life in theatre until all hope of delivering normally was lost.

The doctor told me, “Irene, with you, you are just going for an operation at 10am”. ….I had to break down, I did not know … “if others can push normally, why not me?” At 10 a.m I refused the operation. I told them I don’t want, give me time ……I had feared the theatre because with me I knew whoever goes to theatre, does not come back. They just die like that. I imagined very many things

Multidimensional sources of fear were reported in this study. One mother who experienced excessive bleeding and a retained placenta regretted the decision she had made of delivering at home: “being with aunt alone I feared, I felt my life was going and regretted not having been in hospital”. The mistreatment of women by health care providers was sofrightening that one mother vowed never again to deliver in that hospital as she expressed it:

“... I forced to deliver myself”….in that difficulty situation I went through, I got scared, I feared the midwives of the main hospital (government). I feared too much, I said next time when I deliver, at least I go to private but not go back to main hospital. (Rose, a mother of 4 children) .

The negative stories (the past experiences by other mothers) about the institutional care were noted to be far reaching and a source of childbirth fears regarding the place of delivery. One mother who presumed and perceived hospital care negatively resorted to practices that undermine the quality of birth outcomes as she gave birth at the TBA’s home and gave her account:

“I refused going to hospital. I had no appetite of going there. What I hear threatened me. I hear in the hospital they don’t care about you, you care for yourself. ……..You are seeing this one is complaining, that one grumbling, another one is dying, I avoided such things. I said at least, for me let me die from here (TBA’s) and those other ones die there in hospital” (Amina, an 18-year-old primepara).

Meaning attached to childbirth experiences: The individual woman’s and societal interpretations

The individuals’ childbirth experience meaning.

The individual women interviewed had varying personal interpretations of their birth experiences. The sense made out of it was determined by what preoccupied the woman at that time of labour, the transpirations of the day and the outcomes. The supremacy of God in the event of childbirth was strongly expressed by many women but in union with self-belief and determination of an individual. The women were convinced that God had to be in control for a successful birth. One woman said; …. things to do with childbirth, it is God’s grace and others affirmed:

You must believe in yourself and believe in God. ….for me during birth, I said yes I will do it… I became firm and pushed the baby. Believing in yourself helps you to push the baby (Zaharah, 24 years, mother of one) .

“ It’s not an easy thing but when you are determined, God can be by your side, yah then you will get a child” (Irene, a 26-year-old first time mother).

As some women believed childbirth had a strong bearing on one’s personal effort put in during labour, to others birthing without complications was perceived and directly associated with “being strong and brave” as accounts below indicated:

.... people used to consider me as a weak person and thought I would not manage to give birth by myself… but I demonstrated that I am strong , (She stressed the point very happily, entire group went into laughter)…I pushed the baby without any problem (Amina, an 18 year old, primepara)

Anna, a 28-year-old first time mother also added:

“….. others when they start to push, they push and even die. I had to push and I saw the baby; then what I concluded is that i am brave because it is not easy there”

Societal and cultural interpretation of childbirth experiences

When women were asked to comment on how society perceived the different birth experiences they had gone through, the responses were cross cutting despite mothers being from different tribal and cultural backgrounds. The socio- cultural interpretations were mainly bent on the type of birth a woman went through. A mother was considered a strong woman if she gave birth well (vaginally) and the operated were regarded bewitched, failures or weak women.

Caroline, who had 3 consecutive operations said:

The Gisu’s themselves think that when you go for an operation, …. you are bewitched. …you are unable to have children, unable to be a real housewife; … not a good house woman to make a child for somebody.

Irene, a first- time mother who delivered by caesarean birth was insulted by the community members as she explained:

Culturally, to the illiterate, they assume whoever goes for an operation failed to push. You are a weak woman. So, they were insulting me “eeeh she had just fattened, but you see, she failed to push the baby”.

The study explored and presents the childbirth experiences among postnatal mothers and the meaning attributed to such experiences. The themes that emerged majorly focused on childbirth pains and management, institutional care and support, social support, childbirth fears and the meaning attributed to their childbirth experiences.

Childbirth pains and management