An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Life Crafting as a Way to Find Purpose and Meaning in Life

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Technology and Operations Management, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

- PMID: 31920827

- PMCID: PMC6923189

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02778

Having a purpose in life is one of the most fundamental human needs. However, for most people, finding their purpose in life is not obvious. Modern life has a way of distracting people from their true goals and many people find it hard to define their purpose in life. Especially at younger ages, people are searching for meaning in life, but this has been found to be unrelated to actually finding meaning. Oftentimes, people experience pressure to have a "perfect" life and show the world how well they are doing, instead of following up on their deep-felt values and passions. Consequently, people may need a more structured way of finding meaning, e.g., via an intervention. In this paper, we discuss evidence-based ways of finding purpose, via a process that we call "life crafting." This process fits within positive psychology and the salutogenesis framework - an approach focusing on factors that support human health and well-being, instead of factors that cause disease. This process ideally starts with an intervention that entails a combination of reflecting on one's values, passions and goals, best possible self, goal attainment plans, and other positive psychology intervention techniques. Important elements of such an intervention are: (1) discovering values and passion, (2) reflecting on current and desired competencies and habits, (3) reflecting on present and future social life, (4) reflecting on a possible future career, (5) writing about the ideal future, (6) writing down specific goal attainment and "if-then" plans, and (7) making public commitments to the goals set. Prior research has shown that personal goal setting and goal attainment plans help people gain a direction or a sense of purpose in life. Research findings from the field of positive psychology, such as salutogenesis, implementation intentions, value congruence, broaden-and-build, and goal-setting literature, can help in building a comprehensive evidence-based life-crafting intervention. This intervention can aid individuals to find a purpose in life, while at the same time ensuring that they make concrete plans to work toward this purpose. The idea is that life crafting enables individuals to take control of their life in order to optimize performance and happiness.

Keywords: Ikigai; goal setting; life crafting; meaning in life; positive psychology; scalable life-crafting intervention; self-concordance; well-being and happiness.

Copyright © 2019 Schippers and Ziegler.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- From Shattered Goals to Meaning in Life: Life Crafting in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. de Jong EM, Ziegler N, Schippers MC. de Jong EM, et al. Front Psychol. 2020 Oct 15;11:577708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577708. eCollection 2020. Front Psychol. 2020. PMID: 33178081 Free PMC article.

- Optimizing Students' Mental Health and Academic Performance: AI-Enhanced Life Crafting. Dekker I, De Jong EM, Schippers MC, De Bruijn-Smolders M, Alexiou A, Giesbers B. Dekker I, et al. Front Psychol. 2020 Jun 3;11:1063. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01063. eCollection 2020. Front Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32581935 Free PMC article. Review.

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, Moraleda C, Rogers L, Daniels K, Green P. Crider K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1;2(2022):CD014217. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014217. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36321557 Free PMC article.

- The Life Crafting Scale: Development and Validation of a Multi-Dimensional Meaning-Making Measure. Chen S, van der Meij L, van Zyl LE, Demerouti E. Chen S, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Mar 7;13:795686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.795686. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35330727 Free PMC article.

- Self-Control as Conceptual Framework to Understand and Support People Who Use Drugs During Sex. Platteau T, Florence E, de Wit JBF. Platteau T, et al. Front Public Health. 2022 Jun 15;10:894415. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.894415. eCollection 2022. Front Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35784207 Free PMC article. Review.

- Comparison of psychopathology, purpose in life and moral courage between nursing home and hospital healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Echeverria I, Bonet L, Benito A, López J, Almodóvar-Fernández I, Peraire M, Haro G. Echeverria I, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 Aug 7;14(1):18305. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68983-7. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 39112550 Free PMC article.

- Examining the Impact of Race and Poverty on the Relationship Between Purpose in Life and Functional Health: Insights from the HANDLS Study. Tan SC, Gamaldo AA, Evans MK, Zonderman AB. Tan SC, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2024 May 21. doi: 10.1007/s40615-024-02021-0. Online ahead of print. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2024. PMID: 38771450

- Forms of Peer Victimization and School Adjustment Among Japanese Adolescents: A Multilevel Analysis. Kawabata Y. Kawabata Y. J Youth Adolesc. 2024 Jun;53(6):1441-1453. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-01967-y. Epub 2024 Mar 30. J Youth Adolesc. 2024. PMID: 38555340

- Longitudinal processes among humility, social justice activism, transcendence, and well-being. Jankowski PJ, Sandage SJ, Wang DC, Zyphur MJ, Crabtree SA, Choe EJ. Jankowski PJ, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Mar 8;15:1332640. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1332640. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 38524294 Free PMC article.

- The Holistic Life-Crafting Model: a systematic literature review of meaning-making behaviors. van Zyl LE, Custers NCM, Dik BJ, van der Vaart L, Klibert J. van Zyl LE, et al. Front Psychol. 2023 Nov 23;14:1271188. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1271188. eCollection 2023. Front Psychol. 2023. PMID: 38078256 Free PMC article.

- Addis D. R., Wong A. T., Schacter D. L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia 45, 1363–1377. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016, PMID: - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Al Taher R. (2019). The 5 founding fathers and a history of positive psychology. Available at: https://positivepsychology.com/founding-fathers/ (Accessed December 3, 2019).

- Anderson R. (2001). Embodied writing and reflections on embodiment. J. Transpers. Psychol. 33, 83–98.

- Anić P., Tončić M. (2013). Orientations to happiness, subjective well-being and life goals. Psihologijske teme 22, 135–153. https://hrcak.srce.hr/100702

- Antonovsky A. (1996). The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 11, 11–18. 10.1093/heapro/11.1.11 - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Frontiers Media SA

- PubMed Central

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Advertisement

Purpose in Life: A Reconceptualization for Very Late Life

- Research Paper

- Published: 14 February 2022

- Volume 23 , pages 2337–2348, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Keith A. Anderson 1 ,

- Noelle L. Fields 1 ,

- Jessica Cassidy 1 &

- Lisa Peters-Beumer 2

714 Accesses

5 Citations

14 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

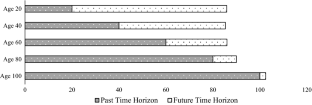

Purpose in life has been defined as having goals, aims, objectives, and a sense of directedness that give meaning to one’s life and existence. Scales that measure purpose in life reflect this future-oriented conceptualization and research using these measures has consistently found that purpose in life tends to be lower for older adults than for those in earlier stages of life. In this article, we use an illustrative case study to explore the concept of purpose in life in very late life and critically challenge existing conceptualizations and measures of purpose in life. We examine the two most commonly used measures of purpose in life, the Purpose in Life Test and the Ryff Purpose Subscale and identify specific items that should be reconsidered for use with older adults in very late life. Guided by Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, we then reconceptualize purpose in life in very late life and posit that it consists of three domains—the retrospective past, the near present, and the transcendental post-mortem. We conclude with suggestions on the development of new measures of purpose in life in very late life that are reflective of this shift in time horizons and the specific characteristics of this unique time in life.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Purpose in Life and Associated Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms

Life Project Scale: a new measure to assess the coherence of the intended future

Aging with Purpose: Developmental Changes and Benefits of Purpose in Life Throughout the Lifespan

Explore related subjects.

- Medical Ethics

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Ardelt, M. (2007). Wisdom, religiosity, purpose in life, and death attitudes of aging adults. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 139–158). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Google Scholar

Amaral, A. S., Afonso, R. M., Brandao, D., Teixeira, L., & Ribeiro, O. (2021). Resilience in very advanced ages: A study with Centenarians. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 93 (1), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020926839

Article Google Scholar

Araujo, L., Ribeiro, O., & Paul, C. (2017). The role of existential beliefs within the relation of centenarians’ health and well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 56 , 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0297-5

Arosio, B., Ostan, R., Mari, D., Damanti, S., Ronchetti, F., Arcudi, S., Scurti, M., Franeschi, C., & Monti, D. (2017). Cognitive status in the oldest old and centenarians: A condition crucial for quality of life methodologically difficult to assess. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 165 , 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2017.02.010

Baltes, P. B., Lindenberger, U., & Staudinger, U.M. (2006). Life-span theory in developmental psychology. In R.M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 569–664). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111

Beker, N., Sikkes, S. A. M., Hulsman, M., Tesi, N., van der Lee, S. J., Scheltens, P., & Holstege, H. (2020). Longitudinal maintenance of cognitive health in centenarians in the 100-plus study. JAMA Network Open, 3 (2), e200094. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0094

Bishop, A. (2011). Spirituality and religiosity connections to mental and physical health among the oldest old. In L. Poon & J. Cohen-Mansfield (Eds.), Understanding well-being in the oldest old (pp. 227–239). Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71 (5), 574–579.

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67 (3), 304–310.

Butler, R. N. (1963). The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry, 26 (1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

Carstensen, L. L. (1991). Selectivity theory: Social activity in lifer-span context. In K. W. Schaie (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Vol. 11, pp. 195–217). Springer.

Carstensen, L. L. (1995). Evidence for a lifespan theory of socioemotional selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4 , 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512261

Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of sense of time on human development. Science, 312 , 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

Charles, S. T., Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2003). Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 132 (2), 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310

Cheng, A., Leung, Y., & Brodaty, H. (2021). A systematic review of the associations, mediators and moderators of life satisfaction, positive affect and happiness in near-centenarians and centenarians. Aging & Mental Health . https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891197

Cheng, A., Leung, Y., Harrison, F., & Brodaty, H. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression in near-centenarians and centenarians: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 31 (11), 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610219000802

Chu, Q., Gruhn, D., & Holland, A. M. (2018). Before I die: The impact of time horizon and age on bucket-list goals. GeroPsych, 31 (3), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000190

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20 (2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1969). Manual of instructions for the Purpose in Life Test . Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy.

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7 , 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2

Duarte, N., Teixeira, L., Ribeiro, O., & Paul, C. (2014). Frailty phenotype criteria in centenarians: Findings from the Oporto Centenarian Study. European Geriatric Medicine, 5 (6), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurger.2014.09.015

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed . W.W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning . Pocket Books.

Hedberg, P., Brulin, C., & Aléx, L. (2009). Experiences of purpose in life when becoming and being a very old woman. Journal of Women and Aging, 21 (2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952840902837145

Hedberg, P., Brulin, C., Aléx, L., & Gustafson, Y. (2011). Purpose in life over a five- year period: A longitudinal study among a very old population. International Psychogeriatrics, 23 (5), 806–813. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610210002279

Hedberg, P., Gustafson, Y., Aléx, L., & Brulin, C. (2010). Depression in relation to purpose in life among a very old population. A five-year follow-up study. Aging & Mental Health, 14 (6), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713216

Hedberg, P., Gustafson, Y., Brulin, C., & Aléx, L. (2013). Purpose in life among very old men. Advances in Aging Research, 2 (3), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.4236/aar.2013.23014

Herr, M., Jeune, B., Fors, S., Andersen-Ranberg, K., Ankri, J., Arai, Y., et al. (2018). Frailty and associated factors among centenarians in the 5-COOP countries. Gerontology, 64 (6), 521–531.

Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science, 25 (7), 1482–1486.

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: Systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85 (4), 403–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017702908

Jopp, D. S., Boerner, K., Ribeiro, O., & Rott, C. (2016a). Life at age 100: An international research agenda for centenarian studies. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 28 (3), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2016.1161693

Jopp, D. S., Park, M.-K.S., Lehrfeld, J., & Paggi, M. E. (2016b). Physical, cognitive, social and mental health in near-centenarians and centenarians living in New York City: Findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. BMC Geriatrics, 16 (1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0167-0

Kastbom, L., Milberg, A., & Karlsson, M. (2017). A good death from the perspective of palliative cancer patients. Journal of Supportive Care in Cancer, 25 , 933–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3483-9

Kim, H., Theyer, B., & Munn, J. C. (2019). The relationship between perceived ageism and depressive symptoms in later life: Understanding the mediating effects of self-perception of aging and purpose in life using structural equation modeling. Educational Gerontology, 45 (2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1583403

Kitayama, S., Berg, M. K., & Chopik, W. J. (2020). Culture and well-being in late adulthood: Theory and evidence. American Psychologist, 75 (4), 567. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000614

Krok, D. (2015). The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 54 , 2292–2308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9983-3

Lewis, N. A., Turiano, N. A., Payne, B. R., & Hill, P. L. (2017). Purpose in life and cognitive functioning in adulthood. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition: Section b, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 24 (6), 662–671.

Martinson, M., & Berridge, C. (2015). Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The Gerontologist, 255 (1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu037

McKee, P. (2008). Plato’s theory of late life reminiscence. Journal of Aging, Humanities, and the Arts, 2 (3–4), 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325610802370720

Moreman, C. M. (2018). Beyond the threshold: Afterlife beliefs and experiences in the world religions . Rowman & Littlefield.

Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., & Wicker, E. (2018). Purpose in life and positive health outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 21 (2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2017.0063

Pew Research Center. (2014). Religious Landscape Study: Belief in heaven . https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/belief-in-heaven/

Pinquart, M. (2002). Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: A meta-analysis. Ageing International, 27 (2), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-002-1004-2

Reker, G. T., Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1987). Meaning and purpose in life and well-being: A life span perspective. Journal of Gerontology, 42 (1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.44

Ribeiro, C. C., Yassuda, M. S., & Neri, A. L. (2020). Purpose in life in adulthood and older adulthood: Integrative review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25 (6), 2127–2142. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.20602018

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37 , 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57 , 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in science and practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83 (1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 , 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Schulenberg, S. E., Schnetzer, L. W., & Buchanan, E. M. (2011). The purpose in life test-short form: Development and psychometric support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12 , 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9231-9

Shaffer, J. (2021). Centenarians, supercentenarians: We must develop new measurements suitable for our oldest old. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 655497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655497

Social Security Administration. (2021). Retirement & survivors’ benefits: Life expectancy calculator. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/population/longevity.html

Tam, W., Poon, S. N., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H., & Wu, X. V. (2021). The effectiveness of reminiscence-based intervention on improving psychological well-being in cognitively intact older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103847

Tornstam, L. (1989). Gero-transcendence: A reformation of the disengagement theory. Aging, 1 (1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03323876

Windsor, T. D., Curtis, R. G., & Luszcz, M. A. (2015). Sense of purpose as a psychological resource for aging well. Developmental Psychology, 51 (7), 975–986.

Xu, X., Zhao, Y., Xia, S., Cui, P., Tang, W., Hu, X., & Wu, B. (2020). Quality of life and its influencing factors among centenarians in Nanjing, China: A cross sectional study. Social Indication Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02399-4

Yalom, I. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Humanistic Psychologist, 36 , 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1432735

Yang, J. A., Wilhelmi, B. L., & McGlynn, K. (2018). Enhancing meaning when facing later life losses. Clinical Gerontologist, 41 (5), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1432735

Download references

This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Social Work, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX, USA

Keith A. Anderson, Noelle L. Fields & Jessica Cassidy

Center for Gerontology, Concordia University Chicago, River Forest, IL, USA

Lisa Peters-Beumer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Keith A. Anderson .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Consent to participate, consent for publication, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Anderson, K.A., Fields, N.L., Cassidy, J. et al. Purpose in Life: A Reconceptualization for Very Late Life. J Happiness Stud 23 , 2337–2348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00512-7

Download citation

Accepted : 08 February 2022

Published : 14 February 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00512-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Purpose in life

- Very late life

- Socioemotional selectivity theory

- Centenarians

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 72, 2021, review article, the science of meaning in life.

- Laura A. King 1 , and Joshua A. Hicks 2

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 72:561-584 (Volume publication date January 2021) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921

- First published as a Review in Advance on September 08, 2020

- Copyright © 2021 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Meaning in life has long been a mystery of human existence. In this review, we seek to demystify this construct. Focusing on the subjective experience of meaning in life, we review how it has been measured and briefly describe its correlates. Then we review evidence that meaning in life, for all its mystery, is a rather commonplace experience. We then define the construct and review its constituent facets: comprehension/coherence, purpose, and existential mattering/significance. We review the many experiences that have been shown to enhance meaning in life and close by considering important remaining research questions about this fascinating topic.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Adler JM , Lodi-Smith J , Philippe FL , Houle I 2016 . The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well-being: a review of the field and recommendations for the future. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 20 : 2 142– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. 1993 . The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 36 : 6 725– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. 1991 . Meanings of Life New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Hofmann W , Summerville A , Reiss PT , Vohs KD 2020 . Everyday thoughts in time: experience sampling studies of mental time travel. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46 : 12 1631 – 48 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR. 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 3 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Vohs KD. 2002 . The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. Handbook of Positive Psychology CR Snyder, SJ Lopez 608– 18 Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Vohs KD , Oettingen G 2016 . Pragmatic prospection: how and why people think about the future. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 20 : 1 3– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , von Hippel W 2020 . Meaning and evolution: why nature selected human minds to use meaning. Evol. Stud. Imagin. Cult. 4 : 1 1– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Becker E. 1973 . The Denial of Death New York: Free Press [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer ET , Westerhof GJ , Emmerik-de Jong M 2008 . The effects of integrative reminiscence on meaning in life: Results of a quasi-experimental study. Aging Ment. Health 12 : 5 639– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA , Barnes LL , Buchman AS , Bennett DA 2009 . Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosom. Med. 71 : 5 574– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA , Buchman AS , Wilson RS , Yu L , Schneider JA , Bennett DA 2012 . Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. JAMA Psychiatry 69 : 5 499– 506 [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter M , Baumann U , Borasio GD , Fegg MJ 2012 . Systematic review of meaning in life assessment instruments. Psycho-Oncology 21 : 1034– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Bronk KC. 2011 . The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: a grounded model. New Dir. Youth Dev. 132 : 31– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Camus A. 1955 . An Absurd Reasoning: The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays New York: Vintage [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL , Isaacowitz DM , Charles ST 1999 . Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 54 : 3 165– 81 [Google Scholar]

- Chu STW , Fung HH , Chu L 2019 . Is positive affect related to meaning in life differently in younger and older adults? A time sampling study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B In press. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz086 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA , Neimeyer RA. 2010 . Measuring meaning: searching for and making sense of spousal loss in late-life. Death Stud 34 : 9 804– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Corona CD , Van Orden KA , Wisco BE , Pietrzak RH 2019 . Meaning in life moderates the association between morally injurious experiences and suicide ideation among US combat veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychol. Trauma 11 : 6 614– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Costin V , Vignoles VL. 2020 . Meaning is about mattering: evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 118 : 4 864– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino PJ. 2006 . Death contemplation, growth, and defense: converging evidence of dual-existential systems. Psychol. Inq. 17 : 278– 87 [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh JC. 1977 . The seeking of noetic goals test (SONG): A complementary scale to the purpose in life test (PIL). J. Clin. Psychol. 33 : 3 900– 7 [Google Scholar]

- Crumbaugh JC , Maholick LT. 1964 . An experimental study in existentialism: the psychometric approach to Frankl's concept of noogenic neurosis. J. Clin. Psychol. 20 : 200– 7 [Google Scholar]

- Dar KA , Iqbal N. 2019 . Religious commitment and well-being in college students: examining conditional indirect effects of meaning in life. J. Relig. Health 58 : 6 2288– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Davis CG , Nolen-Hoeksema S , Larson J 1998 . Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: two construals of meaning. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 75 : 2 561– 74 [Google Scholar]

- Davis WE , Hicks JA. 2013 . Judgments of meaning in life following an existential crisis. See Hicks & Routledge 2013 163– 74

- de St. Aubin E 2013 . Generativity and the meaning of life. See Hicks & Routledge 2013 241– 55

- Debats DL , Drost J , Hansen P 1995 . Experiences of meaning in life: a combined qualitative and quantitative approach. Br. J. Psychol. 86 : 3 359– 75 [Google Scholar]

- DeCarvalho RJ. 2000 . The growth hypothesis and self-actualization: an existential alternative. Humanist. Psychol. 28 : 59– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Dik BJ , Byrne ZS , Steger MF 2013 . Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Ebersole P. 1998 . Types and depth of written life meanings. The Human Quest for Meaning: A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications PTP Wong, PS Fry 179– 91 Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ME , Van Tongeren DR 2020 . Meaning mediates the association between suffering and well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 15 : 6 722 – 33 [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. 2018 . Social Beings: Core Motives in Social Psychology New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. 1984 . 1946 . Man's Search for Meaning New York: Washington Square Press. Rev. , updat. ed.. [Google Scholar]

- George LS , Park CL. 2016 . Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: toward integration and new research questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 20 : 205– 20 [Google Scholar]

- George LS , Park CL. 2017 . The multidimensional existential meaning scale: a tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 12 : 613– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Halusic M , King LA. 2013 . What makes life meaningful: Positive mood works in a pinch. The Psychology of Meaning KD Markman, T Proulx, MJ Lindberg 445– 64 Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger M. 1982 . 1927 . Being and Time , transl. J Macquarrie, E Robinson New York: Harper & Row [Google Scholar]

- Heine S , Proulx T , Vohs K 2006 . The meaning maintenance model: on the coherence of social motivations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10 : 88– 110 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2013a . On knowing more than we can tell: intuition and the human experience of meaning. J. Posit. Psychol. 8 : 471– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2013b . The origins of meaning: objective reality, the unconscious mind, and awareness. See Hicks & Routledge 2013 87– 99

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2014a . Life is pretty meaningful. Am. Psychol. 69 : 561– 74 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2014b . (The feeling of) meaning-as-information. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18 : 153– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2016 . Meaning in life and intuition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 110 : 477– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , King LA. 2019 . Routines and meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45 : 688– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Heintzelman SJ , Trent J , King LA 2013 . Encounters with objective coherence and the experience of meaning in life. Psychol. Sci. 24 : 991– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ , Flett GL. 2004 . Purpose in life, satisfaction with life, and suicide ideation in a clinical sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26 : 2 127– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , Cicero DC , Trent J , Burton CM , King LA 2010a . Positive affect, intuition, and feelings of meaning. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 98 : 6 967– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , King LA. 2007 . Meaning in life and seeing the big picture: positive affect and global focus. Cogn. Emot. 21 : 7 1577– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , King LA. 2008 . Religious commitment and positive mood as information about meaning in life. J. Res. Personal. 42 : 1 43– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , King LA. 2009a . Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 4 : 6 471– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , King LA. 2009b . Meaning in life as a subjective judgment and a lived experience. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 3 : 4 638– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , Routledge C 2013 . The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , Schlegel RJ , King LA 2010b . Social threats, happiness, and the dynamics of meaning in life judgments. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36 : 1305– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JA , Trent J , Davis WE , King LA 2012 . Positive affect, meaning in life, and future time perspective: an application of socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 27 : 1 181– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL , Turiano NA. 2014 . Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7 1482– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL , Turiano NA , Mroczek DK , Burrow AL 2016 . The value of a purposeful life: Sense of purpose predicts greater income and net worth. J. Res. Personal. 65 : 38– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Hocking WE. 1957 . The Meaning of Immortality in Human Experience Westport, CT: Greenwood [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S , Post R , Sherman M 2020 . Awareness of meaning in life is protective against burnout among family physicians: a CERA study. Fam. Med. 52 : 1 11– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Huta V , Waterman AS. 2014 . Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 15 : 6 1425– 56 [Google Scholar]

- James W. 1893 . The Principles of Psychology 1 New York: Holt [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. 1985 . The aftermath of victimization: rebuilding shattered assumptions. Trauma and Its Wake CR Figley 15– 35 Bristol, PA: Brunner/Mazel [Google Scholar]

- Juhl J , Routledge C. 2013 . Nostalgia bolsters perceptions of a meaningful self in a meaningful world. See Hicks & Routledge 2013 213– 26

- Kahneman D , Diener E , Schwarz N 1999 . Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y , Strecher VJ , Kim E , Falk EB 2019 . Purpose in life and conflict-related neural responses during health decision-making. Health Psychol 38 : 6 545– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES , Delaney SW , Kubzansky LD 2019a . Sense of purpose in life and cardiovascular disease: underlying mechanisms and future directions. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 21 : 11 135 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J , Christy AG , Schlegel RJ , Donnellan MB , Hicks JA 2018 . Existential ennui: examining the reciprocal relationship between self-alienation and academic amotivation. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9 : 7 853– 62 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J , Seto E , Schlegel RJ , Hicks JA 2019b . Thinking about a new decade in life increases personal self-reflection: a replication and reinterpretation of Alter and Hershfield's 2014 findings. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 117 : e27– 34 [Google Scholar]

- King LA. 2012 . Meaning: effortless and ubiquitous. Meaning, Mortality, and Choice: The Social Psychology of Existential Concerns M Mikulincer, P Shaver 129– 44 Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- King LA , Heintzelman SJ , Ward SJ 2016 . Beyond the search for meaning: the contemporary science of meaning in life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 211– 16 [Google Scholar]

- King LA , Hicks JA , Abdelkhalik J 2009 . Death, life, scarcity, and value: an alternative approach to the meaning of death. Psychol. Sci. 20 : 1459– 62 [Google Scholar]

- King LA , Hicks JA , Krull JL , Del Gaiso AK 2006 . Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 90 : 1 179– 96 [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM , Beaver JK. 2013 . A meaningful life is worth living: meaning in life as a suicide resiliency factor. Psychiatry Res 210 : 3 934– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Klinger E. 1977 . Meaning and Void: Inner Experience and the Incentives in People's Lives Minneapolis: Univ. Minn. Press [Google Scholar]

- Klinger E. 1998 . The search for meaning in evolutionary perspective and its clinical implications. The Human Quest for Meaning: A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications PTP Wong, PS Fry 27– 50 Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- Klinger E , Cox WM. 2011 . Motivation and the goal theory of current concerns. Handbook of Motivational Counseling: Goal-Based Approaches to Assessment and Intervention with Addiction and Other Problems WM Cox, E Klinger 3– 47 New York: Wiley Blackwell [Google Scholar]

- Kobau R , Sniezek J , Zack MM , Lucas RE , Burns A 2010 . Well-being assessment: an evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2 : 272– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Koltko-Rivera ME. 2004 . The psychology of worldviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8 : 3– 58 [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. 2003 . Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 58 : 3 S160– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Krause N , Hayward RD. 2014 . Assessing stability and change in a second-order confirmatory factor model of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. 15 : 2 237– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Krause N , Rainville G. 2020 . Age differences in meaning in life: exploring the mediating role of social support. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 88 : 104008 [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski AW , Chen X , Dechesne M , Fishman S , Orehek E 2009 . Fully committed: suicide bomber's motivation and the quest for personal significance. Political Psychol 30 : 331– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM , Stillman TF , Baumeister RF , Fincham FD , Hicks JA , Graham SM 2010 . Family as a salient source of meaning in young adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 5 : 5 367– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM , Stillman TF , Hicks JA , Kamble S , Baumeister RF , Fincham FD 2013 . To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 39 : 11 1418– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Leontiev DA. 2013 . Personal meaning: a challenge for psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 8 : 459– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Li Z , Lui Y , Peng K , Hicks JA 2020 . Developing a quadripartite existential meaning scale and exploring the internal structure of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. In press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00256-2 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S , Brooks NB , Spelke ES 2019 . Origins of the concepts cause, cost, and goal in prereaching infants. PNAS 116 : 36 17747– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Martela F , Ryan RM , Steger MF 2018 . Meaningfulness as satisfaction of autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: comparing the four satisfactions and positive affect as predictors of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. 19 : 5 1261– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Martela F , Steger MF. 2016 . The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 11 : 5 531 – 45 [Google Scholar]

- Martin LL , Campbell WK , Henry CD 2004 . The roar of awakening: mortality acknowledgment as a call to authentic living. Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology J Greenberg, SL Koole, T Pyszczynski 431– 48 New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP , Olson BD. 2010 . Personality development: continuity and change over the life course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61 : 517– 42 [Google Scholar]

- McGregor I , Little BR. 1998 . Personal projects, happiness, and meaning: on doing well and being yourself. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 74 : 494– 512 [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE , Kashdan TB. 2009 . Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: an integrative, testable theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 13 : 3 242– 51 [Google Scholar]

- Miao M , Gan Y. 2019 . How does meaning in life predict proactive coping? The self‐regulatory mechanism on emotion and cognition. J. Personal. 87 : 3 579– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Mota NP , Tsai J , Kirwin PD , Sareen J , Southwick SM , Pietrzak RH 2016 . Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident physical disability in aging US military veterans. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 24 : 9 706– 14 [Google Scholar]

- Newman DB , Nezlek JB , Thrash TM 2018 . The dynamics of searching for meaning and presence of meaning in daily life. J. Personal. 86 : 3 368– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Newman DB , Sachs ME , Stone AA , Schwarz N 2020 . Nostalgia and well-being in daily life: an ecological validity perspective. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 118 : 2 325– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Norton MI , Gino F. 2014 . Rituals alleviate grieving for loved ones, lovers, and lotteries. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143 : 1 266– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S , Diener E. 2014 . Residents of poor nations have a greater sense of meaning in life than residents of wealthy nations. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 422– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Owens GP , Steger MF , Whitesell AA , Herrera CJ 2009 . Relationships among posttraumatic stress disorder, guilt, and meaning in life for military veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 22 : 654– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. 2005 . Religion and meaning. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality RF Paloutzian, CL Park 295– 314 New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. 2010 . Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 136 : 2 257– 301 [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M. 2001 . The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychol. Bull. 127 : 5 651– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T , Taylor J. 2016 . When the buffer breaks: disrupted terror management in posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 4 286– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Ray DG , Gomillion S , Pintea AI , Hamlin I 2019 . On being forgotten: Memory and forgetting serve as signals of interpersonal importance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 116 : 2 259– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Rivera GN , Christy AG , Kim J , Vess M , Hicks JA , Schlegel RJ 2019 . Understanding the relationship between perceived authenticity and well-being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 23 : 1 113– 26 [Google Scholar]

- Rivera GN , Vess M , Hicks JA , Routledge C 2020 . Awe and meaning: elucidating complex effects of awe experiences on meaning in life. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50 : 2 392– 405 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M , McCullough BC. 1981 . Mattering: inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Res. Community Ment. Health 2 : 163– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C , Vess M 2018 . Handbook of Terror Management Theory London: Academic [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM , Deci EL. 2001 . On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52 : 141 – 66 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan WS , Ryan RM. 2019 . Toward a social psychology of authenticity: exploring within-person variation in autonomy, congruence, and genuineness using self-determination theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 23 : 1 99– 112 [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. 1989 . Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 57 : 6 1069– 81 [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD , Singer BH. 2008 . Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 9 : 13– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Sartre J-P. 1956 . Being and Nothingness New York: Philos. Libr. [Google Scholar]

- Schaw JA. 2000 . Narcissism as a motivational structure: the problem of personal significance. Psychiatry 63 : 219– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF , Wrosch C , Baum A , Cohen S , Martire LM et al. 2006 . The life engagement test: assessing purpose in life. J. Behav. Med. 29 : 3 291– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel RJ , Hicks JA , Arndt J , King LA 2009 . Thine own self: true self-concept accessibility and meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 96 : 2 473– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel RJ , Hicks JA , King LA , Arndt J 2011 . Feeling like you know who you are: perceived true self-knowledge and meaning in life. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37 : 745– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N , Clore GL. 1988 . How do I feel about it? Informative functions of affective states. Affect, Cognition, and Social Behavior K Fiedler, J Forgas 44– 62 Toronto: Hogrefe Int. [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C , Wildschut T. 2018 . Finding meaning in nostalgia. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 22 : 1 48– 61 [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. 2002 . Authentic Happiness New York: Free Press [Google Scholar]

- Seto E , Hicks JA , Vess M , Geraci L 2016 . The association between vivid thoughts of death and authenticity. Motiv. Emot. 40 : 4 520– 40 [Google Scholar]

- Shiah YJ , Chang F , Chiang SK , Lin IM , Tam WCC 2015 . Religion and health: anxiety, religiosity, meaning of life and mental health. J. Relig. Health 54 : 1 35– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Silver RL , Boon C , Stones MH 1983 . Searching for meaning in misfortune: making sense of incest. J. Soc. Issues 39 : 2 81– 101 [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF. 2012 . Experiencing meaning in life: optimal functioning at the nexus of spirituality, psychopathology, and well-being. The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications PTP Wong 165– 84 New York: Routledge. , 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Dik BJ. 2010 . Work as meaning: Individual and organizational benefits of engaging in meaningful work. Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Work PA Linley, S Harrington, N Garcea 131– 42 New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Frazier P. 2005 . Meaning in life: one link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 52 : 4 574– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Frazier P , Oishi S , Kaler M 2006 . The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 53 : 1 80– 93 [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Kashdan TB. 2009 . Depression and everyday social activity, intimacy, and well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 56 : 289– 300 [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Kashdan TB , Sullivan BA , Lorentz D 2008 . Understanding the search for meaning in life: personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. J. Personal. 76 : 199– 228 [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF , Oishi S , Kashdan TB 2009 . Meaning in life across the life span: levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 4 : 1 43– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A , Fancourt D. 2019 . Leading a meaningful life at older ages and its relationship with social engagement, prosperity, health, biology, and time use. PNAS 116 : 4 1207– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Stillman TF , Lambert NM , Fincham FD , Baumeister RF 2011 . Meaning as magnetic force: evidence that meaning in life promotes interpersonal appeal. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2 : 1 13– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A. 2020 . Living the good life: a meta-analysis of authenticity, well-being and engagement. Personal. Individ. Differ. 153 : 109645 [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB , Read SJ. 1981 . Self-verification processes: how we sustain our self-conceptions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 17 : 4 351– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Szpunar KK. 2010 . Episodic future thought: an emerging concept. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5 : 2 142– 62 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. 1989 . Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy L. 1983 . 1882 . A Confession , transl. D. Patterson New York: W.W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tov W , Lee HW. 2016 . A closer look at the hedonics of everyday meaning and satisfaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 111 : 4 585– 609 [Google Scholar]

- Trent J , King LA. 2010 . Predictors of rapid vs. thoughtful judgments of meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 5 : 439– 51 [Google Scholar]

- Trent J , Lavelock C , King LA 2013 . Processing fluency, positive affect, and meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 8 : 135– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Turk-Browne NB , Scholl BJ , Chun MM , Johnson MK 2008 . Neural evidence of statistical learning: efficient detection of visual regularities without awareness. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 : 1934– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff JA , Silver RC , Holman EA 2008 . Searching for and finding meaning in collective trauma: results from a national longitudinal study of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 95 : 3 709– 22 [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL , Nitschke JB , Dolski I , Jackson DC , Dalton KM et al. 2004 . Making a life worth living: neural correlates of well-being. Psychol. Sci. 15 : 6 367– 72 [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg WAP , Igou ER , Sedikides C 2013 . In search of meaningfulness: nostalgia as an antidote to boredom. Emotion 13 : 450– 61 [Google Scholar]

- Vess M , Hoeldtke R , Leal SA , Sanders CS , Hicks JA 2018 . The subjective quality of episodic future thought and the experience of meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 13 : 4 419– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Vess M , Rogers R , Routledge C , Hicks JA 2017 . When being far away is good: exploring how mortality salience, regulatory mode, and goal progress affect judgments of meaning in life. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 47 : 1 82– 91 [Google Scholar]

- Vess M , Routledge C , Landau MJ , Arndt J 2009 . The dynamics of death and meaning: the effects of death-relevant cognitions and personal need for structure on perceptions of meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97 : 4 728– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ , King LA. 2016a . Socrates’ dissatisfaction, a happiness arms race, and the trouble with eudaimonic well-being. Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being J Vittersø 523– 31 New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ , King LA. 2016b . Poor but happy? Money, mood, and experienced and expected meaning in life. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7 : 463– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ , King LA. 2017 . Work and the good life: how work can promote meaning in life. Res. Organ. Behav. 37 : 59– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Waytz A , Hershfield HE , Tamir DI 2015 . Mental simulation and meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 108 : 2 336– 55 [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. 2012 . Ostracism: the impact of being rendered meaningless. Meaning, Mortality, and Choice: The Social Psychology of Existential Concerns M Mikulincer, P Shaver 309– 24 Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Womick J , Atherton B , King LA 2020 . Lives of significance (and purpose and coherence): narcissism, meaning in life, and subjective well-being. Heliyon 6 : 5 e03982 [Google Scholar]

- Womick J , Ward SJ , Heintzelman SJ , Woody B , King LA 2019 . The existential function of right-wing authoritarianism. J. Personal. 87 : 1056– 73 [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID. 1980 . Existential Psychotherapy New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- You S , Lim SA. 2019 . Religious orientation and subjective well-being: the mediating role of meaning in life. J. Psychol. Theol. 47 : 1 34– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Purpose in Life Predicts Better Emotional Recovery from Negative Stimuli

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America, Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America, Center for Investigating Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America

Affiliation Center for Women's Health and Health Disparities Research, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America

Affiliation Centre for Integrative Neuroscience and Neurodynamics, School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America, Institute on Aging, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, United States of America

- Stacey M. Schaefer,

- Jennifer Morozink Boylan,

- Carien M. van Reekum,

- Regina C. Lapate,

- Catherine J. Norris,

- Carol D. Ryff,

- Richard J. Davidson

- Published: November 13, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080329

- Reader Comments

Purpose in life predicts both health and longevity suggesting that the ability to find meaning from life’s experiences, especially when confronting life’s challenges, may be a mechanism underlying resilience. Having purpose in life may motivate reframing stressful situations to deal with them more productively, thereby facilitating recovery from stress and trauma. In turn, enhanced ability to recover from negative events may allow a person to achieve or maintain a feeling of greater purpose in life over time. In a large sample of adults (aged 36-84 years) from the MIDUS study (Midlife in the U.S., http://www.midus.wisc.edu/ ), we tested whether purpose in life was associated with better emotional recovery following exposure to negative picture stimuli indexed by the magnitude of the eyeblink startle reflex (EBR), a measure sensitive to emotional state. We differentiated between initial emotional reactivity (during stimulus presentation) and emotional recovery (occurring after stimulus offset). Greater purpose in life, assessed over two years prior, predicted better recovery from negative stimuli indexed by a smaller eyeblink after negative pictures offset, even after controlling for initial reactivity to the stimuli during the picture presentation, gender, age, trait affect, and other well-being dimensions. These data suggest a proximal mechanism by which purpose in life may afford protection from negative events and confer resilience is through enhanced automatic emotion regulation after negative emotional provocation.

Citation: Schaefer SM, Morozink Boylan J, van Reekum CM, Lapate RC, Norris CJ, Ryff CD, et al. (2013) Purpose in Life Predicts Better Emotional Recovery from Negative Stimuli. PLoS ONE 8(11): e80329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080329

Editor: Kevin Paterson, University of Leicester, United Kingdom

Received: May 8, 2013; Accepted: October 2, 2013; Published: November 13, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Schaefer et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging (PO1-AG020166), the National Institute on Mental Health (R01 MH043454), and the Waisman Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (Waisman IDDRC), P30HD03352. J. Morozink Boylan was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH018931-22). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Growing evidence from epidemiological research suggests that self-reported psychological well-being is important for both health and longevity, potentially through mechanisms promoting resilience in the face of adversity (see [1] , [2] for recent theoretical reviews). Ryff defined psychological well-being in terms of six key dimensions: autonomy (capacity for self-determination), environmental mastery (ability to manage one’s surrounding world), personal growth (realization of potential), positive relations with others (high-quality relationships), purpose in life (meaning and direction in life), and self-acceptance (positive self-regard) [3] , [4] . Higher levels of purpose in life, personal growth, and positive relations have been linked to lower cardiovascular risk (lower glycosylated hemoglobin, lower weight, lower waist-hip ratios, and higher “good” cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein (HDL)) as well as better neuroendocrine regulation (lower salivary cortisol throughout the day) [5] . Higher profiles on purpose in life and positive relations with others have also been linked to lower inflammatory factors: interleukin-6 (IL-6) and its soluble receptor (sIL-64) [6] , providing empirical support linking these well-being dimensions to better health profiles.

Recent evidence suggests that relative to other dimensions of well-being, purpose in life appears to be particularly important in predicting future health and mortality. In a prospective, longitudinal, epidemiological study of community-dwelling older persons without dementia (Rush Memory and Aging Project), greater purpose in life was associated with better ability to perform day-to-day activities and less mobility disability in the future [7] . Those who reported greater purpose in life exhibited better cognition at follow-up, had a reduced risk of mild cognitive impairment, and a slower rate of cognitive decline [8] . In fact, people who reported high levels of purpose in life (90 th percentile or higher) were 2.4 times more likely to remain free of Alzheimer Disease than people who reported low levels (10 th percentile or lower). Moreover, on postmortem examination of the brain for Alzheimer Disease-related pathology, purpose in life modified the associations between cognition and both global pathologic change and plaque accumulation [9] , suggesting that having greater purpose in life may protect against the detrimental effects of aging-related changes in the brain that have been linked to Alzheimer Disease. Finally, greater purpose in life was associated with a reduced risk of mortality from all causes [10] . Collectively, these findings suggest that the ability to find meaning and direction in life may help buffer or slow the effects of aging and even the ultimate outcome: death.

Besides healthier biomarker levels, slowed effects of aging, and increased longevity, higher levels of psychological well-being have also been associated with lower rates of depression [3] , [4] , [11] , with the dimension of purpose in life consistently showing negative relations with depressive symptomatology. In fact, people in their 50s who report low psychological well-being are more than twice as likely to suffer from depression when in their 60s, even after controlling for previous depression history, personality, demographic, economic, and physical health variables [12] , suggesting that low well-being is a substantial risk factor for future depression. Depression is characterized by high levels of brooding, and often is associated with a ruminative thinking style, and attentional biases suggesting impaired attentional disengagement from negative information (see [13] , [14] for review), which may contribute to the prolonged responses to negative emotional stimuli that have been observed both in psychophysiological and neuroimaging measures, such as prolonged pupil dilations and amygdala activation [15] – [18] . The link between low psychological well-being and the dysregulated emotion observed in depression is further supported by findings from the neuroimaging literature: those reporting higher levels of purpose in life show better regulation of the amygdala (a brain region involved in fear and anxiety-related processes) by the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, such that activity in the amygdala is reduced and the ventral anterior cingulate cortex is activated to a greater extent for negative relative to neutral pictures [19] . Moreover, high purpose in life was associated with slower judgments of the valence of negative relative to neutral pictures, suggesting that persons having goals and a sense of direction in life appraised the negative pictures as less salient and potentially less threatening than did persons with lower levels of purpose in life. Finally, whereas depressive symptomatology has been linked to decreased gray matter volume in the insula [20] , purpose in life (as well as the other well-being dimensions of personal growth and positive relations with others) are positively associated with right insular gray matter volume [21] .

How might purpose in life protect against depression, the body and brain ravages of growing older, and the accumulated toll of stress and challenges over the years? Based on the accumulating evidence, we hypothesize that one mechanism through which high purpose in life may protect against depression and the wear and tear of life stress is by providing a buffer from negative events, promoting reappraisal and motivated coping processes, decreasing brooding and ruminative thinking styles, supporting faster and better recovery, and thus increasing resiliency. Therefore, we hypothesize that higher levels of self-reported purpose in life will be associated with laboratory measures of emotional recovery, specifically, better automatic regulation of negative emotion as exhibited by better recovery from negative emotional stimuli. Importantly, this hypothesis combines phenomenologically-experienced aspects of well-being with objectively measured laboratory assessments of the time course of emotional responses, as this combination may offer unique windows on adaptive human functioning.

Heterogeneity is the rule in emotion research, characterized by large individual differences in how people react to the same emotional event or stimulus, and in how quickly and easily they recover from that stimulus (see Figure 1 for a hypothetical characterization of different emotional time course profiles to the same stimulus). While one person may briefly feel the effect of an unpleasant event, another may suffer a lingering and pervasive effect on mood. These individual differences in emotional reactivity and regulation constitute a person's affective style (see [22] , [23] for theoretical reviews), may be critically influenced by a person’s sense of life purpose, and may also shape how much purpose and meaning one feels, suggesting bi-directional influences between these constructs

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Note that although subjects A and B have similar initial reactivity during the 4 s picture presentation period, after picture offset they differ in emotional recovery. Subject A shows a prolonged poor recovery, whereas Subject B recovers more rapidly. Subject C demonstrates greater initial reactivity with rapid recovery, whereas Subject D exemplifies an individual who may show smaller, blunted emotional reactivity but severely impaired recovery.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080329.g001

Affective psychophysiological research provides tools to measure an individual’s affective state without many of the demand characteristics biasing self-report (for review see [24] , [25] ), allowing for objective characterization of the time course of an individual’s emotional reactivity to and recovery from an emotion-eliciting stimulus [26] . Eyeblink reflex magnitude (EBR) measured to an acoustic startle probe from the orbicularis oculi muscle is emotion-modulated, such that activity is potentiated in the presence of an aversive stimulus and is diminished in the presence of a pleasant stimulus [27] , [28] . Just as facial musculature recordings reflect a person’s affective state and their emotional response to stimuli, the temporal resolution possible with the EBR allows for differentiation of aspects of the emotional response from regulation of that response [26] , [29] , [30] , providing objective estimates of both the magnitude and time course of emotional responses during and following incentives and challenges.

In the current paradigm, EBR measurements were obtained during the picture presentation period and after picture offset. We define emotional reactivity as reflected in measurements during the affective picture presentation when the emotionally evocative stimulus is present, and emotional recovery as measurements obtained after picture offset when the stimulus is no longer present. Parsing the time course in this way allows us to investigate individual differences in both reactivity and recovery. By including both the measures of reactivity and recovery in the same analytic models, we can examine individual differences in our measures during the recovery period unconfounded by variations in reactivity. Referring back to Figure 1 , imagine two people who show similar reactions to the negative stimulus when it is present. One person’s regulatory capacities may facilitate quick recovery from a negative stimulus after it is removed (hypothetical subject B), while another may perseverate and show delayed recovery (hypothetical subject A), such as that observed in depression and dysphoria [15] , [17] , [31] . In this way, we can investigate the differential relationships between emotional reactivity and recovery with higher levels of purpose in life. We predicted that those subjects who reported higher levels of purpose in life would exhibit greater emotional recovery from the negative pictures, controlling for their initial reactivity to these pictures, thereby indicating a more adaptive emotion regulatory profile.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for telephone and mail surveys was obtained from the Social and Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. All participants gave verbal consent, which included assurance of voluntary participation and confidentiality of data. The ethics committee approved the waiver of written consent. Such passive consent is customary for survey research by telephone and mail questionnaire. Ethical approval for the follow-up psychophysiological session was obtained from the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin – Madison and all participants provided written consent.

Participants

The Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) began in 1995 with a national sample of Americans ( N = 7,108) aged 25–74 years [32] . The majority (59.71%) was recruited through random digit dialing (RDD). The remaining respondents included siblings of the RDD sample and a large sample of twins ( N = 1,914). Data collection focused on sociodemographic and psychosocial assessments obtained through phone interviews and self-administered questionnaires. In 2004, these survey assessments were repeated (MIDUS II). The retention rate from MIDUS I to MIDUS II was 75% (adjusted for mortality).

Psychophysiological data were collected on a subset of MIDUS II participants living in the Midwest who were able and willing to travel to our laboratory. The psychophysiology experiment followed the survey assessment on average over two years later (mean (SD) = 881 (26) days). A total of 331 (183 female) participants (age range 36–84 yrs, mean (SD) = 55.41 (11.12) yrs) agreed to participate in our experiment. For a variety of technical, responsivity, and other data quality issues, 253 (147 female/106 male; 185 singletons/68 twin or sibling) participants (age range 36–84 yrs, mean (SD) = 54.68 (10.97) yrs) are included because they completed the psychological well-being questionnaire in the survey assessment and provided a total of 10 or more quantifiable eyeblink responses to the startle probes during the psychophysiological paradigm.

Data and documentation for MIDUS I and II, including all MIDUS projects, are publically available at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR; www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/landing.jsp ).

Given the growing focus on purpose in life as a key predictor of long-term health outcomes and underlying neurophysiology, our hypotheses targeted this particular dimension of well-being, although we included examination of all six scales of well-being collected in the survey assessments in MIDUS II (Scales of Psychological Well-Being; [3] , [4] ). Purpose in life refers to the tendency to derive meaning from life’s experiences and possess a sense of intentionality and goal directedness that guides behavior. The other five dimensions of psychological well-being included autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance. Each scale had seven items (internal consistency for these scales ranged from.69 to.85).

Other Covariates

Other variables used in the analyses included age at the psychophysiological session, gender, the total number of valid eyeblink responses to the startle probes over the course of the psychophysiology experiment, the lag between the survey and psychophysiological assessments in days, trait positive and negative affect measured with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; [33] ), and subjective well-being measures including the Satisfaction with Life Scale [34] and an abbreviated version of the Gratitude Scale [35] asking participants to rate the following two statements: “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “I am grateful to a wide variety of people.” The affect and subjective well-being measures were collected at the time of the psychophysiology session.

A total of 90 International Affective Picture System pictures (IAPS; [36] ) were presented in a randomized sequence. According to the IAPS normative ratings, 30 negative (mean (SD) = 2.89 (0.61)), 30 neutral (mean (SD) = 5.14 (0.52)) and 30 positive (mean (SD) = 7.24 (0.44)) pictures were selected, with the positive and negative pictures matched on arousal (negative pictures mean (SD) = 5.35 (0.54); neutral mean (SD) = 3.22 (0.73); positive mean (SD) = 5.23 (0.73)). All valences were matched on luminosity, complexity, and number of pictures with social content.

Psychophysiological Procedure

The psychophysiological procedures have been described previously (see [30] for additional details). After informed consent was obtained, the participant completed questionnaires. The participant watched the positive, neutral, and negative pictures, and heard acoustic startle probes (50 ms, 105 dB, white noise bursts with very rapid onset time) presented through headphones. Each picture had either a yellow or purple border around it during the first 500 ms of the picture presentation, and participants responded as quickly as possible to the color of the border by pressing one of two keyboard buttons marked with the color with either their index or middle finger of their dominant hand. This color border identification task was used to keep subjects’ attention on the task and ensure they looked at the pictures. Pictures were presented on the screen for 4 s and were preceded by a 1 s fixation screen (see Figure 2 for a schematic of the psychophysiological paradigm’s design). Acoustic startle probes were inserted at three time points (randomized across trials to maintain an average inter-probe interval of ∼ 16 s). One probe occurred during the picture presentation (2900 ms following picture onset), a 2 nd probe occurred 400 ms after picture offset (4400 ms following picture onset), and a 3 rd probe occurred 1900 ms after picture offset (5900 ms following picture onset). A total of nine probes at each of the three time points were presented for each picture valence category, resulting in three non-probed trials for each picture valence. Because preliminary data analysis revealed reduced magnitude EBRs at the 2 nd probe (across all valences), these data were dropped from all further analyses because it suggests the 2 nd probe was affected by prepulse inhibition due to too close temporal proximity to the picture offset [37] . Participants who did not respond with a perceptible EBR on 10 or more of the 81-probed trials were excluded from EBR analyses as they were considered non-responders to the startle probe.

30 positive, 30 negative, and 30 neutral pictures were displayed individually on separate trials. Participants responded as quickly as possible to the border color (purple or yellow) presented during the first 0.5 s of the picture presentation in order to maintain attention during the task. Startle probes were presented at 2900 ms after picture onset (assessing reactivity ) and 1900 ms after picture offset (assessing recovery ). Note: to avoid publication of an IAPS picture, the example negative picture was selected from the author’s personal collection to be representative of a prototypical IAPS picture. As the mother of the baby in the photograph, she has given written informed consent, as outlined in the PLOS consent form, to publication of their photograph.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080329.g002

Analytic Strategy

Manipulation check. We used a linear mixed-effects model to test the expected valence (negative, neutral, positive) modulation effect, a main effect of probe time (reactivity, recovery), and a valence x probe time interaction on EBR magnitude. The model included a family-specific random effect to account for within-family dependence between twins and siblings, as well as a participant-within-family-specific random effect to account for the within-person dependence between EBR measurements. Pairwise comparisons between valences (negative, neutral, and positive) and probe times (reactivity, recovery) were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction.

Tests of purpose in life and the other psychological well-being dimensions predicting EBR measures of emotional reactivity and recovery to negative stimuli. First, zero-order correlations were calculated between purpose in life and the other five psychological well-being dimensions with EBR magnitude measures obtained (1) at the reactivity probe, (2) at the recovery probe, and (3) with a recovery residual reflecting EBR magnitude at the recovery probe regressed on EBR magnitude at the reactivity probe to remove variation due to differences in reactivity (EBR magnitude at the reactivity probe and the recovery probe are inversely correlated, r = –0.15, p = 0.02).