Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Affiliation Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Affiliations Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Department of Psychology, Education and Sport Science, Linneaus University, Kalmar, Sweden

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Network for Empowerment and Well-Being, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Center for Ethics, Law, and Mental Health (CELAM), University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, The Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- Ali Al Nima,

- Patricia Rosenberg,

- Trevor Archer,

- Danilo Garcia

- Published: September 9, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265

- Reader Comments

23 Sep 2013: Nima AA, Rosenberg P, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) Correction: Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLOS ONE 8(9): 10.1371/annotation/49e2c5c8-e8a8-4011-80fc-02c6724b2acc. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/49e2c5c8-e8a8-4011-80fc-02c6724b2acc View correction

Mediation analysis investigates whether a variable (i.e., mediator) changes in regard to an independent variable, in turn, affecting a dependent variable. Moderation analysis, on the other hand, investigates whether the statistical interaction between independent variables predict a dependent variable. Although this difference between these two types of analysis is explicit in current literature, there is still confusion with regard to the mediating and moderating effects of different variables on depression. The purpose of this study was to assess the mediating and moderating effects of anxiety, stress, positive affect, and negative affect on depression.

Two hundred and two university students (males = 93, females = 113) completed questionnaires assessing anxiety, stress, self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and depression. Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted using techniques based on standard multiple regression and hierarchical regression analyses.

Main Findings

The results indicated that (i) anxiety partially mediated the effects of both stress and self-esteem upon depression, (ii) that stress partially mediated the effects of anxiety and positive affect upon depression, (iii) that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression, and (iv) that there was a significant interaction between stress and negative affect, and between positive affect and negative affect upon depression.

The study highlights different research questions that can be investigated depending on whether researchers decide to use the same variables as mediators and/or moderators.

Citation: Nima AA, Rosenberg P, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLoS ONE 8(9): e73265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265

Editor: Ben J. Harrison, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Received: February 21, 2013; Accepted: July 22, 2013; Published: September 9, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Nima et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Mediation refers to the covariance relationships among three variables: an independent variable (1), an assumed mediating variable (2), and a dependent variable (3). Mediation analysis investigates whether the mediating variable accounts for a significant amount of the shared variance between the independent and the dependent variables–the mediator changes in regard to the independent variable, in turn, affecting the dependent one [1] , [2] . On the other hand, moderation refers to the examination of the statistical interaction between independent variables in predicting a dependent variable [1] , [3] . In contrast to the mediator, the moderator is not expected to be correlated with both the independent and the dependent variable–Baron and Kenny [1] actually recommend that it is best if the moderator is not correlated with the independent variable and if the moderator is relatively stable, like a demographic variable (e.g., gender, socio-economic status) or a personality trait (e.g., affectivity).

Although both types of analysis lead to different conclusions [3] and the distinction between statistical procedures is part of the current literature [2] , there is still confusion about the use of moderation and mediation analyses using data pertaining to the prediction of depression. There are, for example, contradictions among studies that investigate mediating and moderating effects of anxiety, stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression. Depression, anxiety and stress are suggested to influence individuals' social relations and activities, work, and studies, as well as compromising decision-making and coping strategies [4] , [5] , [6] . Successfully coping with anxiety, depressiveness, and stressful situations may contribute to high levels of self-esteem and self-confidence, in addition increasing well-being, and psychological and physical health [6] . Thus, it is important to disentangle how these variables are related to each other. However, while some researchers perform mediation analysis with some of the variables mentioned here, other researchers conduct moderation analysis with the same variables. Seldom are both moderation and mediation performed on the same dataset. Before disentangling mediation and moderation effects on depression in the current literature, we briefly present the methodology behind the analysis performed in this study.

Mediation and moderation

Baron and Kenny [1] postulated several criteria for the analysis of a mediating effect: a significant correlation between the independent and the dependent variable, the independent variable must be significantly associated with the mediator, the mediator predicts the dependent variable even when the independent variable is controlled for, and the correlation between the independent and the dependent variable must be eliminated or reduced when the mediator is controlled for. All the criteria is then tested using the Sobel test which shows whether indirect effects are significant or not [1] , [7] . A complete mediating effect occurs when the correlation between the independent and the dependent variable are eliminated when the mediator is controlled for [8] . Analyses of mediation can, for example, help researchers to move beyond answering if high levels of stress lead to high levels of depression. With mediation analysis researchers might instead answer how stress is related to depression.

In contrast to mediation, moderation investigates the unique conditions under which two variables are related [3] . The third variable here, the moderator, is not an intermediate variable in the causal sequence from the independent to the dependent variable. For the analysis of moderation effects, the relation between the independent and dependent variable must be different at different levels of the moderator [3] . Moderators are included in the statistical analysis as an interaction term [1] . When analyzing moderating effects the variables should first be centered (i.e., calculating the mean to become 0 and the standard deviation to become 1) in order to avoid problems with multi-colinearity [8] . Moderating effects can be calculated using multiple hierarchical linear regressions whereby main effects are presented in the first step and interactions in the second step [1] . Analysis of moderation, for example, helps researchers to answer when or under which conditions stress is related to depression.

Mediation and moderation effects on depression

Cognitive vulnerability models suggest that maladaptive self-schema mirroring helplessness and low self-esteem explain the development and maintenance of depression (for a review see [9] ). These cognitive vulnerability factors become activated by negative life events or negative moods [10] and are suggested to interact with environmental stressors to increase risk for depression and other emotional disorders [11] , [10] . In this line of thinking, the experience of stress, low self-esteem, and negative emotions can cause depression, but also be used to explain how (i.e., mediation) and under which conditions (i.e., moderation) specific variables influence depression.

Using mediational analyses to investigate how cognitive therapy intervations reduced depression, researchers have showed that the intervention reduced anxiety, which in turn was responsible for 91% of the reduction in depression [12] . In the same study, reductions in depression, by the intervention, accounted only for 6% of the reduction in anxiety. Thus, anxiety seems to affect depression more than depression affects anxiety and, together with stress, is both a cause of and a powerful mediator influencing depression (See also [13] ). Indeed, there are positive relationships between depression, anxiety and stress in different cultures [14] . Moreover, while some studies show that stress (independent variable) increases anxiety (mediator), which in turn increased depression (dependent variable) [14] , other studies show that stress (moderator) interacts with maladaptive self-schemata (dependent variable) to increase depression (independent variable) [15] , [16] .

The present study

In order to illustrate how mediation and moderation can be used to address different research questions we first focus our attention to anxiety and stress as mediators of different variables that earlier have been shown to be related to depression. Secondly, we use all variables to find which of these variables moderate the effects on depression.

The specific aims of the present study were:

- To investigate if anxiety mediated the effect of stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

- To investigate if stress mediated the effects of anxiety, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

- To examine moderation effects between anxiety, stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression.

Ethics statement

This research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Gothenburg and written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Participants

The present study was based upon a sample of 206 participants (males = 93, females = 113). All the participants were first year students in different disciplines at two universities in South Sweden. The mean age for the male students was 25.93 years ( SD = 6.66), and 25.30 years ( SD = 5.83) for the female students.

In total, 206 questionnaires were distributed to the students. Together 202 questionnaires were responded to leaving a total dropout of 1.94%. This dropout concerned three sections that the participants chose not to respond to at all, and one section that was completed incorrectly. None of these four questionnaires was included in the analyses.

Instruments

Hospital anxiety and depression scale [17] ..

The Swedish translation of this instrument [18] was used to measure anxiety and depression. The instrument consists of 14 statements (7 of which measure depression and 7 measure anxiety) to which participants are asked to respond grade of agreement on a Likert scale (0 to 3). The utility, reliability and validity of the instrument has been shown in multiple studies (e.g., [19] ).

Perceived Stress Scale [20] .

The Swedish version [21] of this instrument was used to measures individuals' experience of stress. The instrument consist of 14 statements to which participants rate on a Likert scale (0 = never , 4 = very often ). High values indicate that the individual expresses a high degree of stress.

Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale [22] .

The Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (Swedish version by Lindwall [23] ) consists of 10 statements focusing on general feelings toward the self. Participants are asked to report grade of agreement in a four-point Likert scale (1 = agree not at all, 4 = agree completely ). This is the most widely used instrument for estimation of self-esteem with high levels of reliability and validity (e.g., [24] , [25] ).

Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule [26] .

This is a widely applied instrument for measuring individuals' self-reported mood and feelings. The Swedish version has been used among participants of different ages and occupations (e.g., [27] , [28] , [29] ). The instrument consists of 20 adjectives, 10 positive affect (e.g., proud, strong) and 10 negative affect (e.g., afraid, irritable). The adjectives are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all , 5 = very much ). The instrument is a reliable, valid, and effective self-report instrument for estimating these two important and independent aspects of mood [26] .

Questionnaires were distributed to the participants on several different locations within the university, including the library and lecture halls. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire after being informed about the purpose and duration (10–15 minutes) of the study. Participants were also ensured complete anonymity and informed that they could end their participation whenever they liked.

Correlational analysis

Depression showed positive, significant relationships with anxiety, stress and negative affect. Table 1 presents the correlation coefficients, mean values and standard deviations ( sd ), as well as Cronbach ' s α for all the variables in the study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t001

Mediation analysis

Regression analyses were performed in order to investigate if anxiety mediated the effect of stress, self-esteem, and affect on depression (aim 1). The first regression showed that stress ( B = .03, 95% CI [.02,.05], β = .36, t = 4.32, p <.001), self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.24, t = −3.20, p <.001), and positive affect ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.19, t = −2.93, p = .004) had each an unique effect on depression. Surprisingly, negative affect did not predict depression ( p = 0.77) and was therefore removed from the mediation model, thus not included in further analysis.

The second regression tested whether stress, self-esteem and positive affect uniquely predicted the mediator (i.e., anxiety). Stress was found to be positively associated ( B = .21, 95% CI [.15,.27], β = .47, t = 7.35, p <.001), whereas self-esteem was negatively associated ( B = −.29, 95% CI [−.38, −.21], β = −.42, t = −6.48, p <.001) to anxiety. Positive affect, however, was not associated to anxiety ( p = .50) and was therefore removed from further analysis.

A hierarchical regression analysis using depression as the outcome variable was performed using stress and self-esteem as predictors in the first step, and anxiety as predictor in the second step. This analysis allows the examination of whether stress and self-esteem predict depression and if this relation is weaken in the presence of anxiety as the mediator. The result indicated that, in the first step, both stress ( B = .04, 95% CI [.03,.05], β = .45, t = 6.43, p <.001) and self-esteem ( B = .04, 95% CI [.03,.05], β = .45, t = 6.43, p <.001) predicted depression. When anxiety (i.e., the mediator) was controlled for predictability was reduced somewhat but was still significant for stress ( B = .03, 95% CI [.02,.04], β = .33, t = 4.29, p <.001) and for self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.20, t = −2.62, p = .009). Anxiety, as a mediator, predicted depression even when both stress and self-esteem were controlled for ( B = .05, 95% CI [.02,.08], β = .26, t = 3.17, p = .002). Anxiety improved the prediction of depression over-and-above the independent variables (i.e., stress and self-esteem) (Δ R 2 = .03, F (1, 198) = 10.06, p = .002). See Table 2 for the details.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t002

A Sobel test was conducted to test the mediating criteria and to assess whether indirect effects were significant or not. The result showed that the complete pathway from stress (independent variable) to anxiety (mediator) to depression (dependent variable) was significant ( z = 2.89, p = .003). The complete pathway from self-esteem (independent variable) to anxiety (mediator) to depression (dependent variable) was also significant ( z = 2.82, p = .004). Thus, indicating that anxiety partially mediates the effects of both stress and self-esteem on depression. This result may indicate also that both stress and self-esteem contribute directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly via experienced level of anxiety (see Figure 1 ).

Changes in Beta weights when the mediator is present are highlighted in red.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g001

For the second aim, regression analyses were performed in order to test if stress mediated the effect of anxiety, self-esteem, and affect on depression. The first regression showed that anxiety ( B = .07, 95% CI [.04,.10], β = .37, t = 4.57, p <.001), self-esteem ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.18, t = −2.23, p = .03), and positive affect ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.04, −.02], β = −.27, t = −4.35, p <.001) predicted depression independently of each other. Negative affect did not predict depression ( p = 0.74) and was therefore removed from further analysis.

The second regression investigated if anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect uniquely predicted the mediator (i.e., stress). Stress was positively associated to anxiety ( B = 1.01, 95% CI [.75, 1.30], β = .46, t = 7.35, p <.001), negatively associated to self-esteem ( B = −.30, 95% CI [−.50, −.01], β = −.19, t = −2.90, p = .004), and a negatively associated to positive affect ( B = −.33, 95% CI [−.46, −.20], β = −.27, t = −5.02, p <.001).

A hierarchical regression analysis using depression as the outcome and anxiety, self-esteem, and positive affect as the predictors in the first step, and stress as the predictor in the second step, allowed the examination of whether anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect predicted depression and if this association would weaken when stress (i.e., the mediator) was present. In the first step of the regression anxiety ( B = .07, 95% CI [.05,.10], β = .38, t = 5.31, p = .02), self-esteem ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.05, −.01], β = −.18, t = −2.41, p = .02), and positive affect ( B = −.03, 95% CI [−.04, −.02], β = −.27, t = −4.36, p <.001) significantly explained depression. When stress (i.e., the mediator) was controlled for, predictability was reduced somewhat but was still significant for anxiety ( B = .05, 95% CI [.02,.08], β = .05, t = 4.29, p <.001) and for positive affect ( B = −.02, 95% CI [−.04, −.01], β = −.20, t = −3.16, p = .002), whereas self-esteem did not reach significance ( p < = .08). In the second step, the mediator (i.e., stress) predicted depression even when anxiety, self-esteem, and positive affect were controlled for ( B = .02, 95% CI [.08,.04], β = .25, t = 3.07, p = .002). Stress improved the prediction of depression over-and-above the independent variables (i.e., anxiety, self-esteem and positive affect) (Δ R 2 = .02, F (1, 197) = 9.40, p = .002). See Table 3 for the details.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.t003

Furthermore, the Sobel test indicated that the complete pathways from the independent variables (anxiety: z = 2.81, p = .004; self-esteem: z = 2.05, p = .04; positive affect: z = 2.58, p <.01) to the mediator (i.e., stress), to the outcome (i.e., depression) were significant. These specific results might be explained on the basis that stress partially mediated the effects of both anxiety and positive affect on depression while stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression. In other words, anxiety and positive affect contributed directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly via the experienced level of stress. Self-esteem contributed only indirectly via the experienced level of stress to explain the variation in depression. In other words, stress effects on depression originate from “its own power” and explained more of the variation in depression than self-esteem (see Figure 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g002

Moderation analysis

Multiple linear regression analyses were used in order to examine moderation effects between anxiety, stress, self-esteem and affect on depression. The analysis indicated that about 52% of the variation in the dependent variable (i.e., depression) could be explained by the main effects and the interaction effects ( R 2 = .55, adjusted R 2 = .51, F (55, 186) = 14.87, p <.001). When the variables (dependent and independent) were standardized, both the standardized regression coefficients beta (β) and the unstandardized regression coefficients beta (B) became the same value with regard to the main effects. Three of the main effects were significant and contributed uniquely to high levels of depression: anxiety ( B = .26, t = 3.12, p = .002), stress ( B = .25, t = 2.86, p = .005), and self-esteem ( B = −.17, t = −2.17, p = .03). The main effect of positive affect was also significant and contributed to low levels of depression ( B = −.16, t = −2.027, p = .02) (see Figure 3 ). Furthermore, the results indicated that two moderator effects were significant. These were the interaction between stress and negative affect ( B = −.28, β = −.39, t = −2.36, p = .02) (see Figure 4 ) and the interaction between positive affect and negative affect ( B = −.21, β = −.29, t = −2.30, p = .02) ( Figure 5 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g003

Low stress and low negative affect leads to lower levels of depression compared to high stress and high negative affect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g004

High positive affect and low negative affect lead to lower levels of depression compared to low positive affect and high negative affect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073265.g005

The results in the present study show that (i) anxiety partially mediated the effects of both stress and self-esteem on depression, (ii) that stress partially mediated the effects of anxiety and positive affect on depression, (iii) that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression, and (iv) that there was a significant interaction between stress and negative affect, and positive affect and negative affect on depression.

Mediating effects

The study suggests that anxiety contributes directly to explaining the variance in depression while stress and self-esteem might contribute directly to explaining the variance in depression and indirectly by increasing feelings of anxiety. Indeed, individuals who experience stress over a long period of time are susceptible to increased anxiety and depression [30] , [31] and previous research shows that high self-esteem seems to buffer against anxiety and depression [32] , [33] . The study also showed that stress partially mediated the effects of both anxiety and positive affect on depression and that stress completely mediated the effects of self-esteem on depression. Anxiety and positive affect contributed directly to explain the variation in depression and indirectly to the experienced level of stress. Self-esteem contributed only indirectly via the experienced level of stress to explain the variation in depression, i.e. stress affects depression on the basis of ‘its own power’ and explains much more of the variation in depressive experiences than self-esteem. In general, individuals who experience low anxiety and frequently experience positive affect seem to experience low stress, which might reduce their levels of depression. Academic stress, for instance, may increase the risk for experiencing depression among students [34] . Although self-esteem did not emerged as an important variable here, under circumstances in which difficulties in life become chronic, some researchers suggest that low self-esteem facilitates the experience of stress [35] .

Moderator effects/interaction effects

The present study showed that the interaction between stress and negative affect and between positive and negative affect influenced self-reported depression symptoms. Moderation effects between stress and negative affect imply that the students experiencing low levels of stress and low negative affect reported lower levels of depression than those who experience high levels of stress and high negative affect. This result confirms earlier findings that underline the strong positive association between negative affect and both stress and depression [36] , [37] . Nevertheless, negative affect by itself did not predicted depression. In this regard, it is important to point out that the absence of positive emotions is a better predictor of morbidity than the presence of negative emotions [38] , [39] . A modification to this statement, as illustrated by the results discussed next, could be that the presence of negative emotions in conjunction with the absence of positive emotions increases morbidity.

The moderating effects between positive and negative affect on the experience of depression imply that the students experiencing high levels of positive affect and low levels of negative affect reported lower levels of depression than those who experience low levels of positive affect and high levels of negative affect. This result fits previous observations indicating that different combinations of these affect dimensions are related to different measures of physical and mental health and well-being, such as, blood pressure, depression, quality of sleep, anxiety, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and self-regulation [40] – [51] .

Limitations

The result indicated a relatively low mean value for depression ( M = 3.69), perhaps because the studied population was university students. These might limit the generalization power of the results and might also explain why negative affect, commonly associated to depression, was not related to depression in the present study. Moreover, there is a potential influence of single source/single method variance on the findings, especially given the high correlation between all the variables under examination.

Conclusions

The present study highlights different results that could be arrived depending on whether researchers decide to use variables as mediators or moderators. For example, when using meditational analyses, anxiety and stress seem to be important factors that explain how the different variables used here influence depression–increases in anxiety and stress by any other factor seem to lead to increases in depression. In contrast, when moderation analyses were used, the interaction of stress and affect predicted depression and the interaction of both affectivity dimensions (i.e., positive and negative affect) also predicted depression–stress might increase depression under the condition that the individual is high in negative affectivity, in turn, negative affectivity might increase depression under the condition that the individual experiences low positive affectivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their openness and suggestions, which significantly improved the article.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AAN TA. Performed the experiments: AAN. Analyzed the data: AAN DG. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: AAN TA DG. Wrote the paper: AAN PR TA DG.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. MacKinnon DP, Luecken LJ (2008) How and for Whom? Mediation and Moderation in Health Psychology. Health Psychol 27 (2 Suppl.): s99–s102.

- 4. Aaroe R (2006) Vinn över din depression [Defeat depression]. Stockholm: Liber.

- 5. Agerberg M (1998) Ut ur mörkret [Out from the Darkness]. Stockholm: Nordstedt.

- 6. Gilbert P (2005) Hantera din depression [Cope with your Depression]. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Prisma.

- 8. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2007) Using Multivariate Statistics, Fifth Edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

- 10. Beck AT (1967) Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- 21. Eskin M, Parr D (1996) Introducing a Swedish version of an instrument measuring mental stress. Stockholm: Psykologiska institutionen Stockholms Universitet.

- 22. Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- 23. Lindwall M (2011) Självkänsla – Bortom populärpsykologi & enkla sanningar [Self-Esteem – Beyond Popular Psychology and Simple Truths]. Lund:Studentlitteratur.

- 25. Blascovich J, Tomaka J (1991) Measures of self-esteem. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS (Red.) Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes San Diego: Academic Press. 161–194.

- 30. Eysenck M (Ed.) (2000) Psychology: an integrated approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 31. Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

- 32. Johnson M (2003) Självkänsla och anpassning [Self-esteem and Adaptation]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- 33. Cullberg Weston M (2005) Ditt inre centrum – Om självkänsla, självbild och konturen av ditt själv [Your Inner Centre – About Self-esteem, Self-image and the Contours of Yourself]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

- 34. Lindén M (1997) Studentens livssituation. Frihet, sårbarhet, kris och utveckling [Students' Life Situation. Freedom, Vulnerability, Crisis and Development]. Uppsala: Studenthälsan.

- 35. Williams S (1995) Press utan stress ger maximal prestation [Pressure without Stress gives Maximal Performance]. Malmö: Richters förlag.

- 37. Garcia D, Kerekes N, Andersson-Arntén A–C, Archer T (2012) Temperament, Character, and Adolescents' Depressive Symptoms: Focusing on Affect. Depress Res Treat. DOI:10.1155/2012/925372.

- 40. Garcia D, Ghiabi B, Moradi S, Siddiqui A, Archer T (2013) The Happy Personality: A Tale of Two Philosophies. In Morris EF, Jackson M-A editors. Psychology of Personality. New York: Nova Science Publishers. 41–59.

- 41. Schütz E, Nima AA, Sailer U, Andersson-Arntén A–C, Archer T, Garcia D (2013) The affective profiles in the USA: Happiness, depression, life satisfaction, and happiness-increasing strategies. In press.

- 43. Garcia D, Nima AA, Archer T (2013) Temperament and Character's Relationship to Subjective Well- Being in Salvadorian Adolescents and Young Adults. In press.

- 44. Garcia D (2013) La vie en Rose: High Levels of Well-Being and Events Inside and Outside Autobiographical Memory. J Happiness Stud. DOI: 10.1007/s10902-013-9443-x.

- 48. Adrianson L, Djumaludin A, Neila R, Archer T (2013) Cultural influences upon health, affect, self-esteem and impulsiveness: An Indonesian-Swedish comparison. Int J Res Stud Psychol. DOI: 10.5861/ijrsp.2013.228.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological Science, School of Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine, California 92697, USA; email: [email protected].

- 3 Division of Primary Care, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 32886587

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

The cumulative science linking stress to negative health outcomes is vast. Stress can affect health directly, through autonomic and neuroendocrine responses, but also indirectly, through changes in health behaviors. In this review, we present a brief overview of ( a ) why we should be interested in stress in the context of health; ( b ) the stress response and allostatic load; ( c ) some of the key biological mechanisms through which stress impacts health, such as by influencing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation and cortisol dynamics, the autonomic nervous system, and gene expression; and ( d ) evidence of the clinical relevance of stress, exemplified through the risk of infectious diseases. The studies reviewed in this article confirm that stress has an impact on multiple biological systems. Future work ought to consider further the importance of early-life adversity and continue to explore how different biological systems interact in the context of stress and health processes.

Keywords: HPA axis; allostatic load; autonomic nervous system; cortisol; genomics.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Coordination of cortisol response to social evaluative threat with autonomic and inflammatory responses is moderated by stress appraisals and affect. Laurent HK, Lucas T, Pierce J, Goetz S, Granger DA. Laurent HK, et al. Biol Psychol. 2016 Jul;118:17-24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.04.066. Epub 2016 May 4. Biol Psychol. 2016. PMID: 27155141 Free PMC article.

- Greater lifetime stress exposure predicts blunted cortisol but heightened DHEA responses to acute stress. Lam JCW, Shields GS, Trainor BC, Slavich GM, Yonelinas AP. Lam JCW, et al. Stress Health. 2019 Feb;35(1):15-26. doi: 10.1002/smi.2835. Epub 2018 Sep 19. Stress Health. 2019. PMID: 30110520 Free PMC article.

- Neuroendocrine coordination and youth behavior problems: A review of studies assessing sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis activity using salivary alpha amylase and salivary cortisol. Jones EJ, Rohleder N, Schreier HMC. Jones EJ, et al. Horm Behav. 2020 Jun;122:104750. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104750. Epub 2020 Apr 21. Horm Behav. 2020. PMID: 32302595 Review.

- Effects of early childhood trauma on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Kempke S, Luyten P, De Coninck S, Van Houdenhove B, Mayes LC, Claes S. Kempke S, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015 Feb;52:14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.027. Epub 2014 Nov 8. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015. PMID: 25459889

- Biomarkers of stress in behavioural medicine. Nater UM, Skoluda N, Strahler J. Nater UM, et al. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013 Sep;26(5):440-5. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328363b4ed. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013. PMID: 23867656 Review.

- Old lessons for new science: How sacred-tree metaphors can inform studies of the public-health benefits of the natural environment. Donovan GH, Derrien M, Wendel K, Michael YL. Donovan GH, et al. Heliyon. 2024 Jul 26;10(15):e35111. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35111. eCollection 2024 Aug 15. Heliyon. 2024. PMID: 39166085 Free PMC article.

- Stress and substance use disorders: risk, relapse, and treatment outcomes. Sinha R. Sinha R. J Clin Invest. 2024 Aug 15;134(16):e172883. doi: 10.1172/JCI172883. J Clin Invest. 2024. PMID: 39145454 Free PMC article. Review.

- Exploring the Interplay between Sleep Quality, Stress, and Somatization among Teachers in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Mancone S, Corrado S, Tosti B, Spica G, Di Siena F, Diotaiuti P. Mancone S, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jul 24;12(15):1472. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12151472. Healthcare (Basel). 2024. PMID: 39120175 Free PMC article.

- Clinical Education: Addressing Prior Trauma and Its Impacts in Medical Settings. McBain SA, Cordova MJ. McBain SA, et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2024 Sep;31(3):501-512. doi: 10.1007/s10880-024-10029-1. Epub 2024 Aug 2. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2024. PMID: 39095585 Review.

- Inflammatory biomarkers and psychological variables to assess quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. González-Moret R, Cebolla-Martí A, Almodóvar-Fernández I, Navarrete J, García-Esparza Á, Soria JM, Lisón JF. González-Moret R, et al. Ann Med. 2024 Dec;56(1):2357738. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2024.2357738. Epub 2024 May 31. Ann Med. 2024. PMID: 38819080 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- PubChem Compound (MeSH Keyword)

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Recent developments in stress and anxiety research

- Published: 01 September 2021

- Volume 128 , pages 1265–1267, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Urs M. Nater 1 , 2

5984 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stress and anxiety are virtually omnipresent in today´s society, pervading almost all aspects of our daily lives. While each and every one of us experiences “stress” and/or “anxiety” at least to some extent at times, the phenomena themselves are far from being completely understood. In stress research, scientists are particularly grappling with the conceptual issue of how to define stress, also with regard to delimiting stress from anxiety or negative affectivity in general. Interestingly, there is no unified theory of stress, despite many attempts at defining stress and its characteristics. Consequently, the available literature relies on a variety of different theoretical approaches, though the theories of Lazarus and Folkman ( 1984 ) or McEwen ( 1998 ) are relatively pervasive in the literature. One key issue in conceptualizing stress is that research has not always differentiated between the perception of a stimulus or a situation as a stressor and the subsequent biobehavioral response (often called the “stress response”). This is important, since, for example, psychological factors such as uncontrollability and social evaluation, i.e. factors that may influence how an individual perceives a potentially stressful stimulus or situation, have been identified as characteristics that elicit particularly powerful physiological stressful responses (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004 ). At the core of the physiological stress response is a complex physiological system, which is located in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the body´s periphery. The complexity of this system necessitates a multi-dimensional assessment approach involving variables that adequately reflect all relevant components. It is also important to consider that the experience of stress and its psychobiological correlates do not occur in a vacuum, but are being shaped by numerous contextual factors (e.g. societal and cultural context, work and leisure time, family and dyadic systems, environmental variables, physical fitness, nutritional status, etc.) and dispositional factors (e.g. genetics, personality, resilience, regulatory capacities, self-efficacy, etc.). Thus, a theoretical framework needs to incorporate these factors. In sum, as stress is considered a multi-faceted and inherently multi-dimensional construct, its conceptualization and operationalization needs to reflect this (Nater 2018 ).

The goal of the World Association for Stress Related and Anxiety Disorders (WASAD) is to promote and make available basic and clinical research on stress-related and anxiety disorders. Coinciding with WASAD’s 3rd International Congress held in September 2021 in Vienna, Austria, this journal publishes a Special Issue encompassing state-of-the art research in the field of stress and anxiety. This special issue collects answers to a number of important questions that need to be addressed in current and future research. Among the most relevant issues are (1) the multi-dimensional assessment that arises as a consequence of a multi-faceted consideration of stress and anxiety, with a particular focus on doing so under ecologically valid conditions. Skoluda et al. 2021 (in this issue) argue that hair as an important source of the stress hormone cortisol should not only be taken as a complementary stress biomarker by research staff, but that lay persons could be also trained to collect hair at the study participants’ homes, thus increasing the ecological validity of studies incorporating this important measure; (2) the incongruence between psychological and biological facets of stress and anxiety that has been observed both in laboratory and field research (Campbell and Ehlert 2012 ). Interestingly, there are behavioral constructs that do show relatively high congruence. As shown in the paper of Vatheuer et al. ( 2021 ), gaze behavior while exposed to an acute social stressor correlates with salivary cortisol, thus indicating common underlying mechanisms; (3) the complex dynamics of stress-related measures that may extend over shorter (seconds to minutes), medium (hours and diurnal/circadian fluctuations), and longer (months, seasonal) time periods. In particular, momentary assessment studies are highly qualified to examine short to medium term fluctuations and interactions. In their study employing such a design, Stoffel and colleagues (Stoffel et al. 2021 ) show ecologically valid evidence for direct attenuating effects of social interactions on psychobiological stress. Using an experimental approach, on the other hand, Denk et al. ( 2021 ) examined the phenomenon of physiological synchrony between study participants; they found both cortisol and alpha-amylase physiological synchrony in participants who were in the same group while being exposed to a stressor. Importantly, these processes also unfold over time in relation to other biological systems; al’Absi and colleagues showed in their study (al’Absi et al. 2021 ) the critical role of the endogenous opioid system and its relation to stress-related analgesia; (4) the influence of contextual and dispositional factors on the biological stress response in various target samples (e.g., humans, animals, minorities, children, employees, etc.) both under controlled laboratory conditions and in everyday life environments. In this issue, Sattler and colleagues show evidence that contextual information may only matter to a certain extent, as in their study (Sattler et al. 2021 ), the biological response to a gay-specific social stressor was equally pronounced as the one to a general social stressor in gay men. Genetic information is probably the most widely researched dispositional factor; Kuhn et al. show in their paper (Kuhn et al. 2021 ) that the low expression variant of the serotonin transporter gene serves as a risk factor for increased stress reactivity, thus clearly indicating the important role of dispositional factors in stress processing. An interesting factor combining both aspects of dispositional and contextual information is maternal care; Bentele et al. ( 2021 ) in their study are able to show that there was an effect of maternal care on the amylase stress response, while no such effect was observed for cortisol. In a similar vein, Keijser et al. ( 2021 ) showed in their gene-environment interaction study that the effects of FKBP5, a gene very closely related to HPA axis regulation, and early life stress on depressive symptoms among young adults was moderated by a positive parenting style; and (5) the role of stress and anxiety as transdiagnostic factors in mental disorders, be it as an etiological factor, a variable contributing to symptom maintenance, or as a consequence of the condition itself. Stress, e.g., as a common denominator for a broad variety of psychiatric diagnoses has been extensively discussed, and stress as an etiological factor holds specific significance in the context of transdiagnostic approaches to the conceptualization and treatment of mental disorders (Wilamowska et al. 2010 ). The HPA axis, specifically, is widely known to be dysregulated in various conditions. Fischer et al. ( 2021 ) discuss in their comprehensive review the role of this important stress system in the context of patients with post-traumatic disorder. Specifically focusing on the cortisol awakening response, Rausch and colleagues provide evidence for HPA axis dysregulation in patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Rausch et al. 2021 ). As part of a longitudinal project on ADHD, Szep et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the possible impact of child and maternal ADHD symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol concentration; although there was no direct association, the findings underline the importance of taking stress-related assessments into consideration in ADHD studies. As the HPA axis is closely interacting with the immune system, Rhein et al. ( 2021 ) examined in their study the predicting role of the cytokine IL-6 on psychotherapy outcome in patients with PTSD, indicating that high reactivity of IL-6 to a stressor at the beginning of the therapy was associated with a negative therapy outcome. The review of Kyunghee Kim et al. ( 2021 ) also demonstrated the critical role of immune pathways in the molecular changes due to antidepressant treatment. As for the therapy, the important role of cognitive-behavioral therapy with its key elements to address both stress and anxiety reduction have been shown in two studies in this special issue, evidencing its successful application in obsessive–compulsive disorder (Ivarsson et al. 2021 ; Hollmann et al. 2021 ). Thus, both stress and anxiety are crucial transdiagnostic factors in various mental disorders, and future research needs elaborate further on their role in etiology, maintenance, and treatment.

In conclusion, a number of important questions are being asked in stress and anxiety research, as has become evident above. The Special Issue on “Recent developments in stress and anxiety research” attempts to answer at least some of the raised questions, and I want to invite you to inspect the individual papers briefly introduced above in more detail.

al’Absi M, Nakajima M, Bruehl S (2021) Stress and pain: modality-specific opioid mediation of stress-induced analgesia. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02401-4

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bentele UU, Meier M, Benz ABE, Denk BF, Dimitroff SJ, Pruessner JC, Unternaehrer E (2021) The impact of maternal care and blood glucose availability on the cortisol stress response in fasted women. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02350-y

Article Google Scholar

Campbell J, Ehlert U (2012) Acute psychosocial stress: does the emotional stress response correspond with physiological responses? Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(8):1111–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.010

Denk B, Dimitroff SJ, Meier M, Benz ABE, Bentele UU, Unternaehrer E, Popovic NF, Gaissmaier W, Pruessner JC (2021) Influence of stress on physiological synchrony in a stressful versus non-stressful group setting. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02384-2

Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME (2004) Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull 130(3):355–391

Fischer S, Schumacher T, Knaevelsrud C, Ehlert U, Schumacher S (2021) Genes and hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in post-traumatic stress disorder. What is their role in symptom expression and treatment response? J Neural Transm (vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02330-2

Hollmann K, Allgaier K, Hohnecker CS, Lautenbacher H, Bizu V, Nickola M, Wewetzer G, Wewetzer C, Ivarsson T, Skokauskas N, Wolters LH, Skarphedinsson G, Weidle B, de Haan E, Torp NC, Compton SN, Calvo R, Lera-Miguel S, Haigis A, Renner TJ, Conzelmann A (2021) Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder: a feasibility study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02409-w

Ivarsson T, Melin K, Carlsson A, Ljungberg M, Forssell-Aronsson E, Starck G, Skarphedinsson G (2021) Neurochemical properties measured by 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy may predict cognitive behaviour therapy outcome in paediatric OCD: a pilot study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02407-y

Keijser R, Olofsdotter S, Nilsson WK, Åslund C (2021) Three-way interaction effects of early life stress, positive parenting and FKBP5 in the development of depressive symptoms in a general population. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02405-0

Kuhn L, Noack H, Skoluda N, Wagels L, Rohr AK, Schulte C, Eisenkolb S, Nieratschker V, Derntl B, Habel U (2021) The association of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and the response to different stressors in healthy males. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02390-4

Kyunghee Kim H, Zai G, Hennings J, Müller DJ, Kloiber S (2021) Changes in RNA expression levels during antidepressant treatment: a systematic review. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02394-0

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publisher Company Inc, New York

Google Scholar

McEwen BS (1998) Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med 338(3):171–179

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nater UM (2018) The multidimensionality of stress and its assessment. Brain Behav Immun 73:159–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.018

Rausch J, Flach E, Panizza A, Brunner R, Herpertz SC, Kaess M, Bertsch K (2021) Associations between age and cortisol awakening response in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02402-3

Rhein C, Hepp T, Kraus O, von Majewski K, Lieb M, Rohleder N, Erim Y (2021) Interleukin-6 secretion upon acute psychosocial stress as a potential predictor of psychotherapy outcome in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02346-8

Sattler FA, Nater UM, Mewes R (2021) Gay men’s stress response to a general and a specific social stressor. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02380-6

Skoluda N, Piroth I, Gao W, Nater UM (2021) HOME vs. LAB hair samples for the determination of long-term steroid concentrations: a comparison between hair samples collected by laypersons and trained research staff. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02367-3

Stoffel M, Abbruzzese E, Rahn S, Bossmann U, Moessner M, Ditzen B (2021) Covariation of psychobiological stress regulation with valence and quantity of social interactions in everyday life: disentangling intra- and interindividual sources of variation. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02359-3

Szep A, Skoluda N, Schloss S, Becker K, Pauli-Pott U, Nater UM (2021) The impact of preschool child and maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02377-1

Vatheuer CC, Vehlen A, von Dawans B, Domes G (2021) Gaze behavior is associated with the cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in the virtual TSST. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02344-w

Wilamowska ZA, Thompson-Hollands J, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH (2010) Conceptual background, development, and preliminary data from the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Depress Anxiety 27(10):882–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20735

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Urs M. Nater

University Research Platform ‘The Stress of Life – Processes and Mechanisms Underlying Everyday Life Stress’, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Urs M. Nater .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nater, U.M. Recent developments in stress and anxiety research. J Neural Transm 128 , 1265–1267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Download citation

Accepted : 13 August 2021

Published : 01 September 2021

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: correlations, affected groups, and covid-19.

- 1 Department of Neurology, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

- 2 Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

- 3 Office for Diversity and Community Engagement, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, United States

- 4 Department of Biology, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, United States

Academic stress may be the single most dominant stress factor that affects the mental well-being of college students. Some groups of students may experience more stress than others, and the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic could further complicate the stress response. We surveyed 843 college students and evaluated whether academic stress levels affected their mental health, and if so, whether there were specific vulnerable groups by gender, race/ethnicity, year of study, and reaction to the pandemic. Using a combination of scores from the Perception of Academic Stress Scale (PAS) and the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS), we found a significant correlation between worse academic stress and poor mental well-being in all the students, who also reported an exacerbation of stress in response to the pandemic. In addition, SWEMWBS scores revealed the lowest mental health and highest academic stress in non-binary individuals, and the opposite trend was observed for both the measures in men. Furthermore, women and non-binary students reported higher academic stress than men, as indicated by PAS scores. The same pattern held as a reaction to COVID-19-related stress. PAS scores and responses to the pandemic varied by the year of study, but no obvious patterns emerged. These results indicate that academic stress in college is significantly correlated to psychological well-being in the students who responded to this survey. In addition, some groups of college students are more affected by stress than others, and additional resources and support should be provided to them.

Introduction

Late adolescence and emerging adulthood are transitional periods marked by major physiological and psychological changes, including elevated stress ( Hogan and Astone, 1986 ; Arnett, 2000 ; Shanahan, 2000 ; Spear, 2000 ; Scales et al., 2015 ; Romeo et al., 2016 ; Barbayannis et al., 2017 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ; Lally and Valentine-French, 2019 ; Matud et al., 2020 ). This pattern is particularly true for college students. According to a 2015 American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment survey, three in four college students self-reported feeling stressed, while one in five college students reported stress-related suicidal ideation ( Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; American Psychological Association, 2020 ). Studies show that a stressor experienced in college may serve as a predictor of mental health diagnoses ( Pedrelli et al., 2015 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Karyotaki et al., 2020 ). Indeed, many mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorder, begin during this period ( Blanco et al., 2008 ; Pedrelli et al., 2015 ; Saleh et al., 2017 ; Reddy et al., 2018 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ).

Stress experienced by college students is multi-factorial and can be attributed to a variety of contributing factors ( Reddy et al., 2018 ; Karyotaki et al., 2020 ). A growing body of evidence suggests that academic-related stress plays a significant role in college ( Misra and McKean, 2000 ; Dusselier et al., 2005 ; Elias et al., 2011 ; Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ; Hj Ramli et al., 2018 ; Reddy et al., 2018 ; Pascoe et al., 2020 ). For instance, as many as 87% of college students surveyed across the United States cited education as their primary source of stress ( American Psychological Association, 2020 ). College students are exposed to novel academic stressors, such as an extensive academic course load, substantial studying, time management, classroom competition, financial concerns, familial pressures, and adapting to a new environment ( Misra and Castillo, 2004 ; Byrd and McKinney, 2012 ; Ekpenyong et al., 2013 ; Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ; Ketchen Lipson et al., 2015 ; Pedrelli et al., 2015 ; Reddy et al., 2018 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Freire et al., 2020 ; Karyotaki et al., 2020 ). Academic stress can reduce motivation, hinder academic achievement, and lead to increased college dropout rates ( Pascoe et al., 2020 ).

Academic stress has also been shown to negatively impact mental health in students ( Li and Lin, 2003 ; Eisenberg et al., 2009 ; Green et al., 2021 ). Mental, or psychological, well-being is one of the components of positive mental health, and it includes happiness, life satisfaction, stress management, and psychological functioning ( Ryan and Deci, 2001 ; Tennant et al., 2007 ; Galderisi et al., 2015 ; Trout and Alsandor, 2020 ; Defeyter et al., 2021 ; Green et al., 2021 ). Positive mental health is an understudied but important area that helps paint a more comprehensive picture of overall mental health ( Tennant et al., 2007 ; Margraf et al., 2020 ). Moreover, positive mental health has been shown to be predictive of both negative and positive mental health indicators over time ( Margraf et al., 2020 ). Further exploring the relationship between academic stress and mental well-being is important because poor mental well-being has been shown to affect academic performance in college ( Tennant et al., 2007 ; Eisenberg et al., 2009 ; Freire et al., 2016 ).

Perception of academic stress varies among different groups of college students ( Lee et al., 2021 ). For instance, female college students report experiencing increased stress than their male counterparts ( Misra et al., 2000 ; Eisenberg et al., 2007 ; Evans et al., 2018 ; Lee et al., 2021 ). Male and female students also respond differently to stressors ( Misra et al., 2000 ; Verma et al., 2011 ). Moreover, compared to their cisgender peers, non-binary students report increased stressors and mental health issues ( Budge et al., 2020 ). The academic year of study of the college students has also been shown to impact academic stress levels ( Misra and McKean, 2000 ; Elias et al., 2011 ; Wyatt et al., 2017 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Defeyter et al., 2021 ). While several studies indicate that racial/ethnic minority groups of students, including Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian American students, are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and suicidality than their white peers ( Lesure-Lester and King, 2004 ; Lipson et al., 2018 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Kodish et al., 2022 ), these studies are limited and often report mixed or inconclusive findings ( Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Kodish et al., 2022 ). Therefore, more studies should be conducted to address this gap in research to help identify subgroups that may be disproportionately impacted by academic stress and lower well-being.

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic is a major stressor that has led to a mental health crisis ( American Psychological Association, 2020 ; Dong and Bouey, 2020 ). For college students, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant changes and disruptions to daily life, elevated stress levels, and mental and physical health deterioration ( American Psychological Association, 2020 ; Husky et al., 2020 ; Patsali et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ; Clabaugh et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2021 ; Lopes and Nihei, 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). While any college student is vulnerable to these stressors, these concerns are amplified for members of minority groups ( Salerno et al., 2020 ; Clabaugh et al., 2021 ; McQuaid et al., 2021 ; Prowse et al., 2021 ; Kodish et al., 2022 ). Identifying students at greatest risk provides opportunities to offer support, resources, and mental health services to specific subgroups.

The overall aim of this study was to assess academic stress and mental well-being in a sample of college students. Within this umbrella, we had several goals. First, to determine whether a relationship exists between the two constructs of perceived academic stress, measured by the Perception of Academic Stress Scale (PAS), and mental well-being, measured by the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS), in college students. Second, to identify groups that could experience differential levels of academic stress and mental health. Third, to explore how the perception of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic affected stress levels. We hypothesized that students who experienced more academic stress would have worse psychological well-being and that certain groups of students would be more impacted by academic- and COVID-19-related stress.

Materials and Methods

Survey instrument.

A survey was developed that included all questions from the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being ( Tennant et al., 2007 ; Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, 2008 ) and from the Perception of Academic Stress Scale ( Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ). The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale is a seven-item scale designed to measure mental well-being and positive mental health ( Tennant et al., 2007 ; Fung, 2019 ; Shah et al., 2021 ). The Perception of Academic Stress Scale is an 18-item scale designed to assess sources of academic stress perceived by individuals and measures three main academic stressors: academic expectations, workload and examinations, and academic self-perceptions of students ( Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ). These shorter scales were chosen to increase our response and study completion rates ( Kost and de Rosa, 2018 ). Both tools have been shown to be valid and reliable in college students with Likert scale responses ( Tennant et al., 2007 ; Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ; Ringdal et al., 2018 ; Fung, 2019 ; Koushede et al., 2019 ). Both the SWEMWBS and PAS scores are a summation of responses to the individual questions in the instruments. For the SWEMWBS questions, a higher score indicates better mental health, and scores range from 7 to 35. Similarly, the PAS questions are phrased such that a higher score indicates lower levels of stress, and scores range from 18 to 90. We augmented the survey with demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, and race/ethnicity) at the beginning of the survey and two yes/no questions and one Likert scale question about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of our survey.

Participants for the study were self-reported college students between the ages of 18 and 30 years who resided in the United States, were fluent in English, and had Internet access. Participants were solicited through Prolific ( https://prolific.co ) in October 2021. A total of 1,023 individuals enrolled in the survey. Three individuals did not agree to participate after beginning the survey. Two were not fluent in English. Thirteen individuals indicated that they were not college students. Two were not in the 18–30 age range, and one was located outside of the United States. Of the remaining individuals, 906 were full-time students and 96 were part-time students. Given the skew of the data and potential differences in these populations, we removed the part-time students. Of the 906 full-time students, 58 indicated that they were in their fifth year of college or higher. We understand that not every student completes their undergraduate studies in 4 years, but we did not want to have a mixture of undergraduate and graduate students with no way to differentiate them. Finally, one individual reported their age as a non-number, and four individuals did not answer a question about their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This yielded a final sample of 843 college students.

Data Analyses

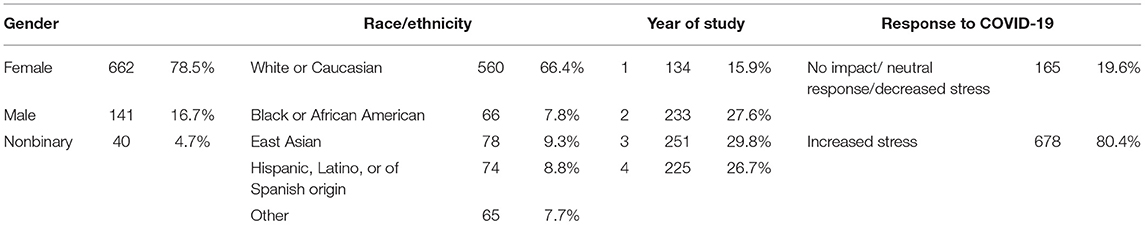

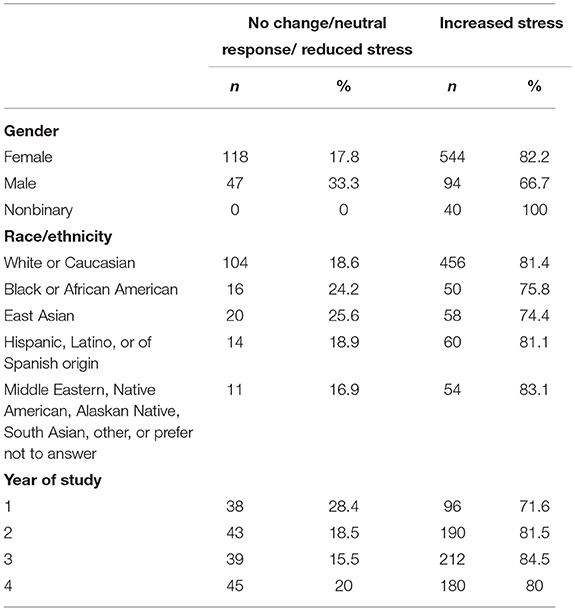

After reviewing the dataset, some variables were removed from consideration due to a lack of consistency (e.g., some students reported annual income for themselves and others reported family income) or heterogeneity that prevented easy categorization (e.g., field of study). We settled on four variables of interest: gender, race/ethnicity, year in school, and response to the COVID-19 pandemic ( Table 1 ). Gender was coded as female, male, or non-binary. Race/ethnicity was coded as white or Caucasian; Black or African American; East Asian; Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin; or other. Other was used for groups that were not well-represented in the sample and included individuals who identified themselves as Middle Eastern, Native American or Alaskan Native, and South Asian, as well as individuals who chose “other” or “prefer not to answer” on the survey. The year of study was coded as one through four, and COVID-19 stress was coded as two groups, no change/neutral response/reduced stress or increased stress.

Table 1 . Characteristics of the participants in the study.

Our first goal was to determine whether there was a relationship between self-reported academic stress and mental health, and we found a significant correlation (see Results section). Given the positive correlation, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with a model testing the main effects of gender, race/ethnicity, and year of study was run in SPSS v 26.0. A factorial MANOVA would have been ideal, but our data were drawn from a convenience sample, which did not give equal representation to all groupings, and some combinations of gender, race/ethnicity, and year of study were poorly represented (e.g., a single individual). As such, we determined that it would be better to have a lack of interaction terms as a limitation to the study than to provide potentially spurious results. Finally, we used chi-square analyses to assess the effect of potential differences in the perception of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels in general among the groups in each category (gender, race/ethnicity, and year of study).

In terms of internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was 0.82 for the SMEMWBS and 0.86 for the PAS. A variety of descriptors have been applied to Cronbach's alpha values. That said, 0.7 is often considered a threshold value in terms of acceptable internal consistency, and our values could be considered “high” or “good” ( Taber, 2018 ).

The participants in our study were primarily women (78.5% of respondents; Table 1 ). Participants were not equally distributed among races/ethnicities, with the majority of students selecting white or Caucasian (66.4% of responders; Table 1 ), or years of study, with fewer first-year students than other groups ( Table 1 ).

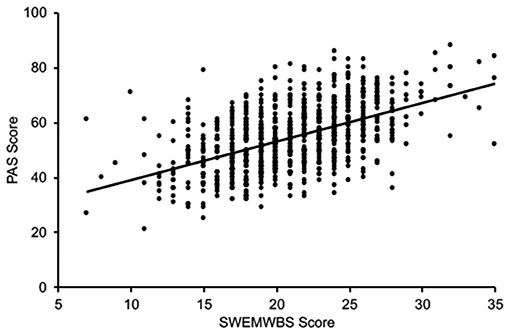

Students who reported higher academic stress also reported worse mental well-being in general, irrespective of age, gender, race/ethnicity, or year of study. PAS and SWEMWBS scores were significantly correlated ( r = 0.53, p < 0.001; Figure 1 ), indicating that a higher level of perceived academic stress is associated with worse mental well-being in college students within the United States.

Figure 1 . SWEMWBS and PAS scores for all participants.

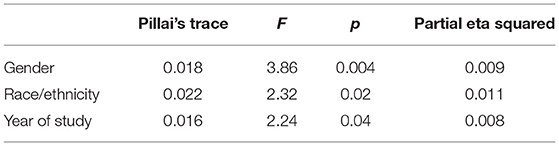

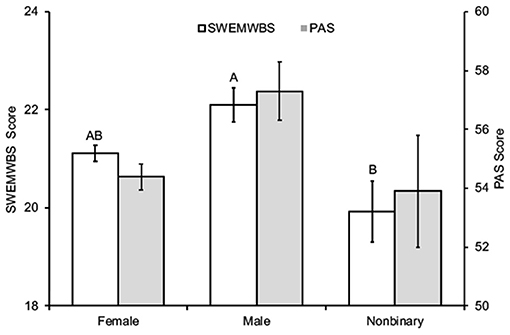

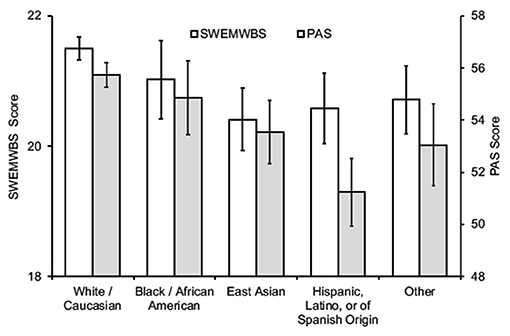

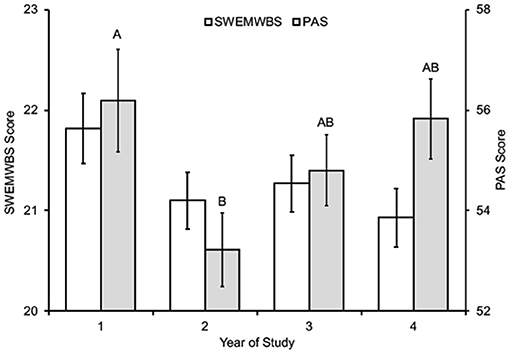

Among the subgroups of students, women, non-binary students, and second-year students reported higher academic stress levels and worse mental well-being ( Table 2 ; Figures 2 – 4 ). In addition, the combined measures differed significantly between the groups in each category ( Table 2 ). However, as measured by partial eta squared, the effect sizes were relatively small, given the convention of 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, and 0.14 = large differences ( Lakens, 2013 ). As such, there were only two instances in which Tukey's post-hoc tests revealed more than one statistical grouping ( Figures 2 – 4 ). For SWEMWBS score by gender, women were intermediate between men (high) and non-binary individuals (low) and not significantly different from either group ( Figure 2 ). Second-year students had the lowest PAS scores for the year of study, and first-year students had the highest scores. Third- and fourth-year students were intermediate and not statistically different from the other two groups ( Figure 4 ). There were no pairwise differences in academic stress levels or mental well-being among racial/ethnic groups.

Table 2 . Results of the MANOVA.

Figure 2 . SWEMWBS and PAS scores according to gender (mean ± SEM). Different letters for SWEMWBS scores indicate different statistical groupings ( p < 0.05).

Figure 3 . SWEMWBS and PAS scores according to race/ethnicity (mean ± SEM).

Figure 4 . SWEMWBS and PAS scores according to year in college (mean ± SEM). Different letters for PAS scores indicate different statistical groupings ( p < 0.05).

The findings varied among categories in terms of stress responses due to the COVID-19 pandemic ( Table 3 ). For gender, men were less likely than women or non-binary individuals to report increased stress from COVID-19 (χ 2 = 27.98, df = 2, p < 0.001). All racial/ethnic groups responded similarly to the pandemic (χ 2 = 3.41, df = 4, p < 0.49). For the year of study, first-year students were less likely than other cohorts to report increased stress from COVID-19 (χ 2 = 9.38, df = 3, p < 0.03).

Table 3 . Impact of COVID-19 on stress level by gender, race/ethnicity, and year of study.

Our primary findings showed a positive correlation between perceived academic stress and mental well-being in United States college students, suggesting that academic stressors, including academic expectations, workload and grading, and students' academic self-perceptions, are equally important as psychological well-being. Overall, irrespective of gender, race/ethnicity, or year of study, students who reported higher academic stress levels experienced diminished mental well-being. The utilization of well-established scales and a large sample size are strengths of this study. Our results extend and contribute to the existing literature on stress by confirming findings from past studies that reported higher academic stress and lower psychological well-being in college students utilizing the same two scales ( Green et al., 2021 ; Syed, 2021 ). To our knowledge, the majority of other prior studies with similar findings examined different components of stress, studied negative mental health indicators, used different scales or methods, employed smaller sample sizes, or were conducted in different countries ( Li and Lin, 2003 ; American Psychological Association, 2020 ; Husky et al., 2020 ; Pascoe et al., 2020 ; Patsali et al., 2020 ; Clabaugh et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2021 ; Lopes and Nihei, 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ).

This study also demonstrated that college students are not uniformly impacted by academic stress or pandemic-related stress and that there are significant group-level differences in mental well-being. Specifically, non-binary individuals and second-year students were disproportionately impacted by academic stress. When considering the effects of gender, non-binary students, in comparison to gender-conforming students, reported the highest stress levels and worst psychological well-being. Although there is a paucity of research examining the impact of academic stress in non-binary college students, prior studies have indicated that non-binary adults face adverse mental health outcomes when compared to male and female-identifying individuals ( Thorne et al., 2018 ; Jones et al., 2019 ; Budge et al., 2020 ). Alarmingly, Lipson et al. (2019) found that gender non-conforming college students were two to four times more likely to experience mental health struggles than cisgender students ( Lipson et al., 2019 ). With a growing number of college students in the United States identifying as as non-binary, additional studies could offer invaluable insight into how academic stress affects this population ( Budge et al., 2020 ).

In addition, we found that second-year students reported the most academic-related distress and lowest psychological well-being relative to students in other years of study. We surmise this may be due to this group taking advanced courses, managing heavier academic workloads, and exploring different majors. Other studies support our findings and suggest higher stress levels could be attributed to increased studying and difficulties with time management, as well as having less well-established social support networks and coping mechanisms compared to upperclassmen ( Allen and Hiebert, 1991 ; Misra and McKean, 2000 ; Liu, X et al., 2019 ). Benefiting from their additional experience, upperclassmen may have developed more sophisticated studying skills, formed peer support groups, and identified approaches to better manage their academic stress ( Allen and Hiebert, 1991 ; Misra and McKean, 2000 ). Our findings suggest that colleges should consider offering tailored mental health resources, such as time management and study skill workshops, based on the year of study to improve students' stress levels and psychological well-being ( Liu, X et al., 2019 ).

Although this study reported no significant differences regarding race or ethnicity, this does not indicate that minority groups experienced less academic stress or better mental well-being ( Lee et al., 2021 ). Instead, our results may reflect the low sample size of non-white races/ethnicities, which may not have given enough statistical power to corroborate. In addition, since coping and resilience are important mediators of subjective stress experiences ( Freire et al., 2020 ), we speculate that the lower ratios of stress reported in non-white participants in our study (75 vs. 81) may be because they are more accustomed to adversity and thereby more resilient ( Brown, 2008 ; Acheampong et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, ethnic minority students may face stigma when reporting mental health struggles ( Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Lee et al., 2021 ). For instance, studies showed that Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian American students disclose fewer mental health issues than white students ( Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ; Lee et al., 2021 ). Moreover, the ability to identify stressors and mental health problems may manifest differently culturally for some minority groups ( Huang and Zane, 2016 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ). Contrary to our findings, other studies cited racial disparities in academic stress levels and mental well-being of students. More specifically, Negga et al. (2007) concluded that African American college students were more susceptible to higher academic stress levels than their white classmates ( Negga et al., 2007 ). Another study reported that minority students experienced greater distress and worse mental health outcomes compared to non-minority students ( Smith et al., 2014 ). Since there may be racial disparities in access to mental health services at the college level, universities, professors, and counselors should offer additional resources to support these students while closely monitoring their psychological well-being ( Lipson et al., 2018 ; Liu, C. H., et al., 2019 ).

While the COVID-19 pandemic increased stress levels in all the students included in our study, women, non-binary students, and upperclassmen were disproportionately affected. An overwhelming body of evidence suggests that the majority of college students experienced increased stress levels and worsening mental health as a result of the pandemic ( Allen and Hiebert, 1991 ; American Psychological Association, 2020 ; Husky et al., 2020 ; Patsali et al., 2020 ; Son et al., 2020 ; Clabaugh et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). Our results also align with prior studies that found similar subgroups of students experience disproportionate pandemic-related distress ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Clabaugh et al., 2021 ; Hunt et al., 2021 ; Jarrett et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2021 ; Chen and Lucock, 2022 ). In particular, the differences between female students and their male peers may be the result of different psychological and physiological responses to stress reactivity, which in turn may contribute to different coping mechanisms to stress and the higher rates of stress-related disorders experienced by women ( Misra et al., 2000 ; Kajantie and Phillips, 2006 ; Verma et al., 2011 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Graves et al., 2021 ). COVID-19 was a secondary consideration in our study and survey design, so the conclusions drawn here are necessarily limited.