Integrity: What it is and Why it is Important

- Public Integrity 20(4):1-15

- Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Rodrigo S. De Bona da Silva

- Yuli Bahriah

- Fitriani Fitriani

- Nadieska Nuñez-Gumila

- Armindo Henriques

- PUBLIC ADMIN

- Yahong Zhang

- Wan-Ju Hung

- Zainal Amin Ayub

- Mohd Dino Khairri Shariffuddin

- Iván Pérez Jordá

- Dejan Jelovac

- Aleksandar Šuleić

- Tebbine Strüwer

- J. Patrick Dobel

- Nicholas Steneck

- Melissa S. Anderson

- Sabine Kleinert

- Bob Surname

- Donald C Menzel

- John A. Rohr

- Herbert J. Storing

- Robert Klitgaard

- H. van Luijk

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Capstone Form and Style

Evidence-based arguments: writing with integrity, writing with integrity: paraphrasing and giving credit.

As we describe in other pages on paraphrasing, successful paraphrasing is the writer’s own explanation or interpretation of another person's ideas or synthesis of other ideas. The goal is to provide a scholarly discussion of other writer’s ideas, provide the original author with credit, and to summarize, synthesize, or expand on the point in an original work.

Ensuring integrity in writing can be a challenge. The standard in American Academic English is to paraphrase and provide a citation to credit the source. This is not the writing expectation in all styles and cultures, so we understand that students sometimes have questions about this. Writing with integrity means the author is writing using his or her own words and being sure to not inadvertently mislead the reader about whether an idea was the writer’s own. Writing with integrity is about rephrasing ideas in the author’s own words and understanding, while also providing credit to the original source.

The example below can be used to understand how to incorporate evidence from previous researchers and authors, providing proper credit to the source. Again, the goal is to write and cite, creating original material and ensuring integrity (avoiding any potential plagiarism concerns).

Example of Uncredited Source

Consider this partial paragraph:

In this example, Organization A is going through a variety of changes in leadership, but this is the norm for organizations in general. Organizations go through change all the time. However, the nature, scope, and intensity of organizational change vary considerably.

Here is the paragraph again, with the second and third sentences bolded and marked in red type:

The red marking is a match from TurnItIn (TII) because those sentences are word-for-word from the original source. TII has matched this text. TII provides an overall percent match in the report. The percentage itself matters less than the user's review of the report. For example, although text may match the 8-word-standard-match-setting, it may not truly be a copy of others' work. Also, TII will match full references; this of course adds to the total matching percentage.

Here is a screenshot of a Google Books search where this text can be found online:

In the screenshot, the words highlighted in yellow are the search phrases, and the red box indicates the sentences that appear in the example paragraph. This text was taken directly out of a book on organizational change. This is problematic because it appears in the example paragraph above to be the writer’s own idea when it is not—it came from this book. This misrepresentation, intentional or not, is an academic integrity issue.

Revising a Paragraph With an Uncredited Source

What if the writer adds a citation.

Note the added parenthetical citation, (Nadler & Tushman, 1994), at the end of the third sentence.

In this example, Organization A is going through a variety of changes in leadership, but these types of changes are the norm for organizations in general. Organizations go through change all the time. However, the nature, scope, and intensity of organizational change vary considerably (Nadler & Tushman, 1994).

This change is incorrect because it is still using the original authors’ words. Though a source is provided, the text should be paraphrased, not word-for-word. This citation does not make the reader aware that the words in the preceding two sentences are the original author’s.

What if the writer adds a citation and quotation marks?

In this revision, the writer has added quotation marks around the words borrowed directly from the original author.

In this example, Organization A is going through a variety of changes in leadership, but these types of changes are the norm for organizations in general. “Organizations go through change all the time. However, the nature, scope, and intensity of organizational change vary considerably” (Nadler & Tushman, 1994, p. 279).

Yes, this would be correct APA formatting to use quotations, if a passage is word-for-word, and provide a citation including the page number. However, at the graduate level of writing and academics, writers should generally avoid quoting and opt for paraphrasing. Writers should avoid quoting other authors because this does not demonstrate scholarship. Walden editors suggest that Walden writers reserve quotations for a few specific instances like definitions, if the author’s original phrasing is the subject of the analysis, or if the idea simply cannot be conveyed accurately by paraphrasing.

So, what is the best course of action?

Paraphrasing the idea from the original source and including a citation is the best course of action.

In this example, Organization A is going through a variety of changes in leadership, but these types of changes are the norm for organizations in general. Although the size of the change and the impact on the organization may fluctuate, organizations are constantly changing (Nadler & Tushman, 1994).

This example includes a paraphrase of the passage that was marked as unoriginal. Here is a reminder of the passage:

Organizations go through change all the time. However, the nature, scope, and intensity of organizational change vary considerably

In the paraphrase above, the same idea is provided and the authors are given credit, but this is done using original writing, not what ends up being plagiarism, and not a quotation (as that does not demonstrate understanding and application).

Writing With Integrity in Doctoral Capstone Studies

For doctoral capstone students, it is also important to adequately cite your sources in your final capstone study. Learn more about writing with integrity in the doctoral capstone specifically on the Form and Style website.

- Previous Page: Citing Sources Properly

- Next Page: Types of Sources to Cite in the Doctoral Capstone

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Academic Integrity

Responsible research and writing habits

Generative ai (artificial intelligence).

- Using Sources and AI

- Academic Writing

- From Research to Writing

- GSD Writing Services

- Grants and Fellowships

- Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

- Theses and Dissertations

Need Help? Be in Touch.

- Ask a Design Librarian

- Call 617-495-9163

- Text 617-237-6641

- Consult a Librarian

- Workshop Calendar

- Library Hours

Central to any academic writing project is crediting (or citing) someone else' words or ideas. The following sites will help you understand academic writing expectations.

Academic integrity is truthful and responsible representation of yourself and your work by taking credit only for your own ideas and creations and giving credit to the work and ideas of other people. It involves providing attribution (citations and acknowledgments) whenever you include the intellectual property of others—and even your own if it is from a previous project or assignment. Academic integrity also means generating and using accurate data.

Responsible and ethical use of information is foundational to a successful teaching, learning, and research community. Not only does it promote an environment of trust and respect, it also facilitates intellectual conversations and inquiry. Citing your sources shows your expertise and assists others in their research by enabling them to find the original material. It is unfair and wrong to claim or imply that someone else’s work is your own.

Failure to uphold the values of academic integrity at the GSD can result in serious consequences, ranging from re-doing an assignment to expulsion from the program with a sanction on the student’s permanent record and transcript. Outside of academia, such infractions can result in lawsuits and damage to the perpetrator’s reputation and the reputation of their firm/organization. For more details see the Academic Integrity Policy at the GSD.

The GSD’s Academic Integrity Tutorial can help build proficiency in recognizing and practicing ways to avoid plagiarism.

- Avoiding Plagiarism (Purdue OWL) This site has a useful summary with tips on how to avoid accidental plagiarism and a list of what does (and does not) need to be cited. It also includes suggestions of best practices for research and writing.

- How Not to Plagiarize (University of Toronto) Concise explanation and useful Q&A with examples of citing and integrating sources.

This fast-evolving technology is changing academia in ways we are still trying to understand, and both the GSD and Harvard more broadly are working to develop policies and procedures based on careful thought and exploration. At the moment, whether and how AI may be used in student work is left mostly to the discretion of individual instructors. There are some emerging guidelines, however, based on overarching values.

- Always ask first if AI is allowed and specifically when and how.

- Always check facts and sources generated by AI as these are not reliable.

- Cite your use of AI to generate text or images. Citation practices for AI are described in Using Sources and AI.

Since policies are changing rapidly, we recommend checking the links below often for new developments, and this page will continue to update as we learn more.

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) from HUIT Harvard's Information Technology team has put together this webpage explaining AI and curating resources about initial guidelines, recommendations for prompts, and recommendations of tools with a section specifically on image-based tools.

- Generative AI in Teaching and Learning at the GSD The GSD's evolving policies, information, and guidance for the use of generative AI in teaching and learning at the GSD are detailed here. The policies section includes questions to keep in mind about privacy and copyright, and the section on tools lists AI tools supported at the GSD.

- AI Code of Conduct by MetaLAB A Harvard-affiliated collaborative comprised of faculty and students sets out recommendations for guidelines for the use of AI in courses. The policies set out here are not necessarily adopted by the GSD, but they serve as a good framework for your own thinking about academic integrity and the ethical use of AI.

- Prompt Writing Examples for ChatGPT+ Harvard Libraries created this resource for improving results through crafting better prompts.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Using Sources and AI >>

- Last Updated: Jul 26, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- How it works

Published by Nicolas at March 20th, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

What Is Academic Integrity – Why Is It Important

In pursuing knowledge, academic integrity serves as a cornerstone, upholding fairness, fostering critical thinking, and ensuring the value of education. But what exactly does it mean, and why is it so crucial in academic environments? Let’s discuss this in detail.

Table of Contents

What Is Academic Integrity?

Academic integrity encompasses honesty, fairness, and responsibility in all academic endeavours. It is about respecting the intellectual property of others, taking ownership of your work, and upholding ethical standards in research, writing, and assessments. This includes but is not limited to, avoiding plagiarism, cheating, and fabrication of data.

The Foundations Of Academic Integrity

Academic integrity stands on the following foundations.

Honesty In Intellectual Pursuits

Academic integrity begins with an unwavering commitment to honesty in intellectual pursuits. This aspect emphasizes the importance of original thought, authentic engagement with course materials, and the responsible use of information.

Students are encouraged to approach assignments, examinations, and research papers with sincerity, cultivating their understanding and skills through genuine effort. By fostering an environment where honesty is valued, educational institutions contribute to developing individuals who can navigate the complexities of academia with integrity.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Plagiarism is one of the most significant threats to academic integrity, posing a direct challenge to originality and intellectual contribution principles. It involves presenting someone else’s work, ideas, or expressions as one’s own without proper acknowledgment.

Academic institutions like universities in Canada take a strong stance against plagiarism due to its potential to undermine the learning process, erode trust, and compromise the integrity of educational outcomes.

Students are urged to understand what constitutes plagiarism and employ effective strategies to avoid it, such as paraphrasing, citing sources accurately, and seeking guidance when in doubt.

Proper Citation And Referencing

Proper citation and referencing are fundamental components of academic integrity, serving as a demonstration of respect for the intellectual property of others. When incorporating external sources into academic work, providing due credit through accurate citation is imperative.

Different academic disciplines may have specific citation styles, such as APA, MLA , or Chicago, and students are expected to adhere to these guidelines meticulously. Understanding the details of citation safeguards against plagiarism and enhances the credibility and legitimacy of one’s own work.

Through meticulous referencing, students contribute to the broader scholarly conversation, acknowledging the contributions of those who have paved the way for their research and ideas.

Why Does Academic Integrity Matter?

The significance of academic integrity extends far beyond simply avoiding repercussions like failing grades or disciplinary actions. It plays a vital role in various aspects of education, both for individuals and institutions:

Fostering A Fair Learning Environment

Imagine a classroom where some students diligently study and complete assignments, while others resort to plagiarism or shortcuts. This creates an unfair advantage for the latter, undermining the true measure of knowledge and skill.

Academic integrity levels the playing field, ensuring everyone has equal opportunity to learn and excel based on their merit.

Promoting Critical Thinking And Deep Learning

When students engage in honest academic practices, they actively grapple with concepts, analyze information, and synthesize knowledge. This fosters critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and a genuine understanding of the subject matter.

Conversely, cheating bypasses this crucial learning process, resulting in superficial knowledge and hindering intellectual growth.

Building Trust And Credibility

Academic institutions rely on trust and integrity to maintain their reputation and the value of their degrees. When students uphold these values, it strengthens the institution’s credibility and ensures the quality of its graduates. Moreover, academic dishonesty erodes trust and casts doubt on the legitimacy of academic achievements.

Preparing Students For Ethical Conduct

The principles of academic integrity transcend the classroom, shaping personal and professional conduct. By practicing honesty and responsibility in their studies, students develop valuable ethical values that translate into future careers and interactions with colleagues and clients.

Ensuring The Integrity Of Research And Knowledge Production

Accurate and reliable research forms the foundation of academic disciplines and advancements in various fields. Fabricating data or plagiarizing findings not only undermines the research itself but also hinders the progress of knowledge creation and can have detrimental consequences in fields like medicine and science.

The 5 Fundamental Values Of Academic Integrity

The five fundamental values of academic integrity are:

This is the most basic value of academic integrity. It means being truthful and forthright in all your academic work. This includes things like not cheating on exams, not plagiarizing, and not fabricating data.

Academic integrity is built on trust. We trust that our classmates and teachers are honest and that they will uphold the same standards of integrity that we do. This trust is essential for creating a healthy learning environment where everyone can feel safe and supported.

Everyone deserves a fair chance to succeed in their academic pursuits. Academic integrity means playing by the rules and giving everyone an equal opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. This includes things like not taking advantage of others or using unauthorized resources.

We should respect ourselves, our classmates, our teachers, and the academic community as a whole. This means treating everyone with dignity and courtesy, even when we disagree with them. It also means respecting the rules and procedures that are in place to ensure fairness and honesty.

- Responsibility

We are all responsible for our academic integrity. This means taking ownership of our work and making sure that it is up to our own standards. It also means being aware of the rules and regulations that govern academic integrity and following them faithfully.

Common Challenges To Maintaining Academic Integrity

Some challenges that are faced by academics in maintaining academic integrity are listed below.

Pressure To Perform

- Students may face intense academic pressure, leading to the temptation to take shortcuts or resort to dishonest practices in pursuit of better grades.

- The fear of failure or the desire to meet external expectations can contribute to compromising academic integrity.

Lack Of Understanding

- Some students may not fully grasp the principles of academic integrity, including what constitutes plagiarism or the importance of proper citation.

- Misunderstandings about academic expectations and guidelines can inadvertently lead to unintentional violations.

Online Learning Challenges

- The shift to online education presents unique challenges, as remote assessments may make monitoring and ensuring academic honesty harder.

- The availability of online resources can also increase the likelihood of plagiarism if not properly managed.

Cultural Differences

- International students may face challenges related to differences in academic cultures and expectations, which can inadvertently lead to breaches of academic integrity.

- Varied cultural attitudes towards collaboration and citation may contribute to unintentional violations.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Strategies To Promote And Sustain Academic Integrity

Educational programs.

- Institutions can implement thorough educational programs to raise awareness about the importance of academic integrity.

- Workshops, seminars, and online modules can help students understand the principles, consequences, and techniques to maintain integrity.

Clear Communication

- Academic institutions should communicate clear expectations regarding academic integrity, including definitions of plagiarism, proper citation practices, and consequences for violations.

- Transparent communication fosters a shared understanding among students, faculty, and staff, creating a culture that values honesty.

Technology Solutions

- Implementing plagiarism detection tools and technologies can act as deterrents and help identify instances of academic dishonesty.

- Secure online examination platforms with monitoring features can be employed to maintain integrity in remote learning environments.

Promoting A Positive Learning Environment

- Create an environment where learning is emphasized over grades, reducing the pressure on students to resort to dishonest practices.

- Encourage collaboration, critical thinking, and a growth mindset, fostering a positive academic culture.

Support And Guidance

- Provide students with access to resources, such as writing centers and academic advisors, to seek guidance on proper citation and academic writing.

- Foster a supportive environment where students feel comfortable discussing challenges related to academic integrity.

How To Maintain Academic Integrity: A Shared Responsibility

Upholding academic integrity is a shared responsibility between students, faculty, and institutions. Here are some ways everyone can contribute:

- Familiarize yourself with your institution’s academic integrity policies and resources.

- Seek help and clarification from instructors when needed, instead of resorting to shortcuts.

- Properly cite sources and give credit to the work of others.

- Report any observed instances of academic misconduct.

- Clearly communicate expectations and guidelines regarding academic integrity in your courses.

- Create assessments that encourage critical thinking and independent work.

- Provide timely feedback and support to students struggling with academic concepts.

- Address suspected cases of academic misconduct fairly and transparently.

Institutions

- Develop and implement clear and detailed academic integrity policies.

- Provide accessible resources and workshops on academic integrity for students and faculty.

- Foster a culture of open communication and encourage reporting of academic misconduct.

- Uphold fair and consistent consequences for violations of academic integrity policies.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is academic integrity.

Academic integrity is the ethical framework guiding honest and principled behaviour in educational pursuits. It involves upholding honesty in assignments, avoiding plagiarism, and giving proper credit through citation, ensuring the credibility and authenticity of academic work.

Why is academic integrity important?

Academic integrity fosters trust, maintains ethical standards, and promotes genuine learning. Upholding honesty in intellectual pursuits, avoiding plagiarism, and proper citation contribute to responsible individuals’ development and educational institutions’ credibility.

How to maintain academic integrity?

Maintain academic integrity by prioritizing originality, avoiding plagiarism through proper citation, understanding and adhering to institutional guidelines, seeking clarification when uncertain, and resisting the temptation to cheat. Uphold ethical standards to ensure honest and authentic academic contributions.

What are the 5 fundamental values of academic integrity?

How does plagiarism affect academic integrity.

Plagiarism undermines academic integrity by misrepresenting intellectual contributions. It erodes trust, devalues original work, and compromises the educational process. Consequences may include academic penalties, damaged reputations, and long-term impacts on personal and professional development.

You May Also Like

Looking for a guide on how to write a thesis statement? 1. Understand the assignment 2. Identify topic 3. Research 4. Revise and 5. Finalize

Cancer research is a vast and dynamic field that plays a pivotal role in advancing our understanding of this complex […]

In Canada, scholarships are generally not taxable if they are for education in a qualifying program. Consult tax regulations or a professional for accurate information.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources, company details.

- How It Works

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

Fostering Integrity in Research (2017)

Chapter: 2 foundations of integrity in research: core values and guiding norms, 2 foundations of integrity in research: core values and guiding norms.

Problems of scientific freedom and responsibility are not new; one need only consider, as examples, the passionate controversies that were stirred by the work of Galileo and Darwin. In our time, however, such problems have changed in character, and have become far more numerous, more urgent and more complex. Science and its applications have become entwined with the whole fabric of our lives and thoughts. . . . Scientific freedom, like academic freedom, is an acquired right, generally accepted by society as necessary for the advancement of knowledge from which society may benefit. Scientists possess no rights beyond those of other citizens except those necessary to fulfill the responsibility arising from their special knowledge, and from the insight arising from that knowledge.

— John Edsall (1975)

Synopsis: The integrity of research is based on adherence to core values—objectivity, honesty, openness, fairness, accountability, and stewardship. These core values help to ensure that the research enterprise advances knowledge. Integrity in science means planning, proposing, performing, reporting, and reviewing research in accordance with these values. Participants in the research enterprise stray from the norms and appropriate practices of science when they commit research misconduct or other misconduct or engage in detrimental research practices.

TRANSMITTING VALUES AND NORMS IN RESEARCH

The core values and guiding norms of science have been studied and written about extensively, with the work of Robert Merton providing a foundation for subsequent work on the sociology of science ( Merton, 1973 ). Merton posited a set of norms that govern good science: (1) Communalism (common ownership of scientific knowledge), (2) Universalism (all scientists can contribute to the advance of knowledge), (3) Disinterestedness (scientists should work for the good of the scientific enterprise as opposed to personal gain), and (4) Organized Skepticism (results should be examined critically before they are accepted). Research on scientists and scientific organizations has also led to a better understanding of

counternorms that appear to conflict with the dominant Mertonian norms but that are recognized as playing an inherent part in the actual practice of science, such as the personal commitment that a scientist may have to a particular hypothesis or theory ( Mitroff, 1974 ).

More recent work on the effectiveness of responsible conduct of research education, covered in more detail in Chapter 9 , explores evidence that at least some scientists may not understand and reflect upon the ethical dimensions of their work ( McCormick et al., 2012 ). Several causes are identified, including a lack of awareness on the part of researchers of the ethical issues that can arise, confidence that they can identify and address these issues without any special training or help, or apprehension that a focus on ethical issues might hinder their progress. An additional challenge arises from the apparent gap “between the normative ideals of science and science’s institutional reward system” ( Devereaux, 2014 ). Chapter 6 covers this issue in more detail. Here, it is important to note that identifying and understanding the values and norms of science do not automatically mean that they will be followed in practice. The context in which values and norms are communicated and transmitted in the professional development of scientists is critically important.

Scientists are privileged to have careers in which they explore the frontiers of knowledge. They have greater autonomy than do many other professionals and are usually respected by other members of society. They often are able to choose the questions they want to pursue and the methods used to derive answers. They have rich networks of social relationships that, for the most part, reinforce and further their work. Whether actively involved in research or employed in some other capacity within the research enterprise, scientists are able to engage in an activity about which they are passionate: learning more about the world and how it functions.

In the United States, scientific research in academia emerged during the late 19th century as an “informal, intimate, and paternalistic endeavor” ( NAS-NAE-IOM, 1992 ). Multipurpose universities emphasized teaching, and research was more of an avocation than a profession. Even today, being a scientist and engaging in research does not necessarily entail a career with characteristics traditionally associated with professions such as law, medicine, architecture, some subfields of engineering, and accounting. For example, working as a researcher does not involve state certification of the practitioner’s expertise as a requirement to practice, nor does it generally involve direct relationships with fee-paying clients. Many professions also maintain an explicit expectation that practitioners will adhere to a distinctive ethical code ( Wickenden, 1949 ). In contrast, scientists do not have a formal, overarching code of ethics and professional conduct.

However, the nature of professional practice even in the traditional professions continues to evolve ( Evetts, 2013 ). Some scholars assert that the concept of professional work should include all occupations characterized by “expert knowledge, autonomy, a normative orientation grounded in community, and

high status, income, and other rewards” ( Gorman and Sandefur, 2011 ). Scientific research certainly shares these characteristics. In this respect, efforts to formalize responsible conduct of research training in the education of researchers often have assumed that this training should be part of the professional development of researchers ( IOM-NRC, 2002 ; NAS-NAE-IOM, 1992 ). However, the training of researchers (and research itself) has retained some “informal, intimate, and paternalistic” features. Attempts to formalize professional development training sometimes have generated resistance in favor of essentially an apprenticeship model with informal, ad hoc approaches to how graduate students and postdoctoral fellows learn how to become professional scientists.

One challenge facing the research enterprise is that informal, ad hoc approaches to scientific professionalism do not ensure that the core values and guiding norms of science are adequately inculcated and sustained. This has become increasingly clear as the changes in the research environment described in Chapter 3 have emerged and taken hold. Indeed, the apparent inadequacy of these older forms of training to the task of socializing and training individuals into responsible research practices is a recurring theme of this report.

Individual scientists work within a much broader system that profoundly influences the integrity of research results. This system, described briefly in Chapter 1 , is characterized by a massive, interconnected web of relationships among researchers, employing institutions, public and private funders, and journals and professional societies. This web comprises unidirectional and bidirectional obligations and responsibilities between the parts of the system. The system is driven by public and private investments and results in various outcomes or products, including research results, various uses of those results, and trained students. However, the system itself has a dynamic that shapes the actions of everyone involved and produces results that reflect the functioning of the system. Because of the large number of relationships between the many players in the web of responsibility, features of one set of relationships may affect other parts of the web. These interdependencies complicate the task of devising interventions and structures that support and encourage the responsible conduct of research.

THE CORE VALUES OF RESEARCH

The integrity of research is based on the foundational core values of science. The research system could not operate without these shared values that shape the behaviors of all who are involved with the system. Out of these values arise the web of responsibilities that make the system cohere and make scientific knowledge reliable. Many previous guides to responsible conduct in research have identified and described these values ( CCA, 2010 ; ESF-ALLEA, 2011 ; IAC-IAP, 2012 ; ICB, 2010 ; IOM-NRC, 2002 ). This report emphasizes six values that are most influential in shaping the norms that constitute research practices and relationships and the integrity of science:

Objectivity

Accountability, stewardship.

This chapter examines each of these six values in turn to consider how they shape, and are realized in, research practices.

The first of the six values discussed in this report—objectivity—describes the attitude of impartiality with which researchers should strive to approach their work. The next four values—honesty, openness, accountability, and fairness—describe relationships among those involved in the research enterprise. The final value—stewardship—involves the relationship between members of the research enterprise, the enterprise as a whole, and the broader society within which the enterprise is situated. Although we discuss stewardship last, it is an essential value that perpetuates the other values.

The hallmark of scientific thinking that differentiates it from other modes of human inquiry and expression such as literature and art is its dedication to rational and empirical inquiry. In this context, objectivity is central to the scientific worldview. Karl Popper (1999) viewed scientific objectivity as consisting of the freedom and responsibility of the researcher to (1) pose refutable hypotheses, (2) test the hypotheses with the relevant evidence, and (3) state the results clearly and unambiguously to any interested person. The goal is reproducibility, which is essential to advancing knowledge through experimental science. If these steps are followed diligently, Popper suggested, any reasonable second researcher should be able to follow the same steps to replicate the work.

Objectivity means that certain kinds of motivations should not influence a researcher’s action, even though others will. For example, if a researcher in an experimental field believes in a particular hypothesis or explanation of a phenomenon, he or she is expected to design experiments that will test the hypothesis. The experiment should be designed in a way that allows the possibility for the hypothesis to be disconfirmed. Scientific objectivity is intended to ensure that scientists’ personal beliefs and qualities—motivations, position, material interests, field of specialty, prominence, or other factors—do not introduce biases into their work.

As will be explored in later chapters, in practice it is not that simple. Human judgment and decisions are prone to a variety of cognitive biases and systematic errors in reasoning. Even the best scientific intentions are not always sufficient to ensure scientific objectivity. Scientific objectivity can be compromised acci-

dentally or without recognition by individuals. In addition, broader biases of the reigning scientific paradigm influence the theory and practice of science ( Kuhn, 1962 ). A primary purpose of scientific replication is to minimize the extent to which experimental findings are distorted by biases and errors. Researchers have a responsibility to design experiments in ways that any other person with different motivations, interests, and knowledge could trust the results. Modern problems related to reproducibility are explored later in the report.

In addition, objectivity does not imply or require that researchers can or should be completely neutral or disinterested in pursuing their work. The research enterprise does not function properly without the organized efforts of researchers to convince their scientific audiences. Sometimes researchers are proven correct when they persist in trying to prove theories in the face of evidence that appears to contradict them.

It is important to note, in addition, Popper’s suggestion that scientific objectivity consists of not only responsibility but freedom . The scientist must be free from pressures and influences that can bias research results. Objectivity can be compromised when institutional expectations, laboratory culture, the regulatory environment, or funding needs put pressure on the scientist to produce positive results or to produce them under time pressure. Scientists and researchers operate in social contexts, and the incentives and pressures of those contexts can have a profound effect on the exercise of scientific methodology and a researcher’s commitment to scientific objectivity.

Scientific objectivity also must coexist with other human motivations that challenge it. As an example of such a challenge, a researcher might become biased in desiring definitive results evaluating the validity of high-profile theories or hypotheses that their experiments were designed to support or refute. Both personal desire to obtain a definitive answer and institutional pressures to produce “significant” conclusions can provide strong motivation to find definitive results in experimental situations. Dedication to scientific objectivity in those settings represents the best guard against scientists finding what they desire instead of what exists. Institutional support of objectivity at every level—from mentors, to research supervisors, to administrators, and to funders—is crucial in counterbalancing the very human tendency to desire definitive outcomes of research.

A researcher’s freedom to advance knowledge is tied to his or her responsibility to be honest . Science as an enterprise producing reliable knowledge is based on the assumption of honesty. Science is predicated on agreed-upon systematic procedures for determining the empirical or theoretical basis of a proposition. Dishonest science violates that agreement and therefore violates a defining characteristic of science.

Honesty is the principal value that underlies all of the other relationship val-

ues. For example, without an honest foundation, realizing the values of openness, accountability, and fairness would be impossible.

Scientific institutions and stakeholders start with the assumption of honesty. Peer reviewers, granting agencies, journal editors, commercial research and development managers, policy makers, and other players in the scientific enterprise all start with an assumption of the trustworthiness of the reporting scientist and research team. Dishonesty undermines not only the results of the specific research but also the entire scientific enterprise itself, because it threatens the trustworthiness of the scientific endeavor.

Being honest is not always straightforward. It may not be easy to decide what to do with outlier data, for example, or when one suspects fraud in published research. A single outlier data point may be legitimately interpreted as a malfunctioning instrument or a contaminated sample. However, true scientific integrity requires the disclosure of the exclusion of a data point and the effect of that exclusion unless the contamination or malfunction is documented, not merely conjectured. There are accepted statistical methods and standards for dealing with outlier data, although questions are being raised about how often these are followed in certain fields ( Thiese et al., 2015 ).

Dishonesty can take many forms. It may refer to out-and-out fabrication or falsification of data or reporting of results or plagiarism. It includes such things as misrepresentation (e.g., avoiding blame, claiming that protocol requirements have been followed when they have not, or producing significant results by altering experiments that have been previously conducted), nonreporting of phenomena, cherry-picking of data, or overenhancing pictorial representations of data. Honest work includes accurate reporting of what was done, including the methods used to do that work. Thus, dishonesty can encompass lying by omission, as in leaving out data that change the overall conclusions or systematically publishing only trials that yield positive results. The “file drawer” effect was first discussed almost 40 years ago; Robert Rosenthal (1979) presented the extreme view that “journals are filled with the 5 percent of the studies that show Type I errors, while the file drawers are filled with the 95 percent of the studies that show non-significant results.” This hides the possibility of results being published from 1 significant trial in an experiment of 100 trials, as well as experiments that were conducted and then altered in order to produce the desired results. The file drawer effect is a result of publication bias and selective reporting, the probability that a study will be published depending on the significance of its results ( Scargle, 2000 ). As the incentives for researchers to publish in top journals increase, so too do these biases and the file drawer effect.

Another example of dishonesty by omission is failing to report all funding sources where that information is relevant to assessing potential biases that might influence the integrity of the work. Conversely, dishonesty can also include reporting of nonexistent funding sources, giving the impression that the research

was conducted with more support and so may have been more thorough than in actuality.

Beyond the individual researcher, those engaged in assessing research, whether those who are funding it or participating in any level of the peer review process, also have fundamental responsibilities of honesty. Most centrally, those assessing the quality of science must be honest in their assessments and aware of and honest in reporting their own conflicts of interest or any cognitive biases that may skew their judgment in self-serving ways. There is also a need to guard against unconscious bias, sometimes by refusing to assess work even when a potential reviewer is convinced that he or she can be objective. Efforts to protect honesty should be reinforced by the organizations and systems within which those assessors function. Universities, research organizations, journals, funding agencies, and professional societies must all work to hold each other to honest interactions without favoritism and with potentially biasing factors disclosed.

Openness is not the same as honesty, but it is predicated on honesty. In the scientific enterprise, openness refers to the value of being transparent and presenting all the information relevant to a decision or conclusion. This is essential so that others in the web of the research enterprise can understand why a decision or conclusion was reached. Openness also means making the data on which a result is based available to others so that they may reproduce and verify results or build on them. In some contexts, openness means listening to conflicting ideas or negative results without allowing preexisting biases or expectations to cloud one’s judgment. In this respect, openness reinforces objectivity and the achievement of reliable observations and results.

Openness is an ideal toward which to strive in the research enterprise. It almost always enhances the advance of knowledge and facilitates others in meeting their responsibilities, be it journal editors, reviewers, or those who use the research to build products or as an input to policy making. Researchers have to be especially conscientious about being open, since the incentive structure within science does not always explicitly reward openness and sometimes discourages it. An investigator may desire to keep data private to monopolize the conclusions that can be drawn from those data without fear of competition. Researchers may be tempted to withhold data that do not fit with their hypotheses or conclusions. In the worst cases, investigators may fail to disclose data, code, or other information underlying their published results to prevent the detection of fabrication or falsification.

Openness is an ideal that may not always be possible to achieve within the research enterprise. In research involving classified military applications, sensitive personal information, or trade secrets, researchers may have an obligation not to disseminate data and the results derived from those data. Disclosure of results

and underlying data may be delayed to allow time for filing a patent application. These sorts of restrictions are more common in certain research settings—such as commercial enterprises and government laboratories—than they are in academic research institutions performing primarily fundamental work. In the latter, openness in research is a long-held principle shared by the community, and it is a requirement in the United States to avoid privileged access that would undermine the institution’s nonprofit status and to maintain the fundamental research exclusion from national security-based restrictions.

As the nature of data changes, so do the demands of achieving openness. For example, modern science is often based on very large datasets and computational implementations that cannot be included in a written manuscript. However, publications describing such results could not exist without the data and code underlying the results. Therefore, as part of the publication process, the authors have an obligation to have the available data and commented code or pseudocode (a high-level description of a program’s operating principle) necessary and sufficient to re-create the results listed in the manuscript. Again, in some situations where a code implementation is patentable, a brief delay in releasing the code in order to secure intellectual property protection may be acceptable. When the resources needed to make data and code available are insufficient, authors should openly provide them upon request. Similar considerations apply to such varied forms of data as websites, videos, and still images with associated text or voiceovers.

Central to the functioning of the research enterprise is the fundamental value that members of the community are responsible for and stand behind their work, statements, actions, and roles in the conduct of their work. At its core, accountability implies an obligation to explain and/or justify one’s behavior. Accountability requires that individuals be willing and able to demonstrate the validity of their work or the reasons for their actions. Accountability goes hand in hand with the credit researchers receive for their contributions to science and how this credit builds their reputations as members of the research enterprise. Accountability also enables those in the web of relationships to rely on work presented by others as a foundation for additional advances.

Individual accountability builds the trustworthiness of the research enterprise as a whole. Each participant in the research system, including researchers, institutional administrators, sponsors, and scholarly publishers, has obligations to others in the web of science and in return should be able to expect consistent and honest actions by others in the system. Mutual accountability therefore builds trust, which is a consequence of the application of the values described in this report.

The purpose of scientific publishing is to advance the state of knowledge through examination by peers who can assess, test, replicate where appropriate, and build on the work being described. Investigators reporting on their work thus

must be accountable for the accuracy of their work. Through this accountability, they form a compact with the users of their work. Readers should be able to trust that the work was performed by the authors as described, with honest and accurate reporting of results. Accountability means that any deviations from the compact would be flagged and explained. Readers then could use these explanations in interpreting and evaluating the work.

Investigators are accountable to colleagues in their discipline or field of research, to the employer and institution at which the work is done, to the funders or other sponsors of the research, to the editors and institutions that disseminate their findings, and to the public, which supports research in the expectation that it will produce widespread benefits. Other participants in the research system have other forms of accountability. Journals are accountable to authors, reviewers, readers, the institutions they represent, and other journals (for the reuse of material, violation of copyright, or other issues of mutual concern). Institutions are accountable to their employees, to students, to the funders of both research and education, and to the communities in which they are located. Organizations that sponsor research are accountable to the researchers whose work they support and to their governing bodies or other sources of support, including the public. These networks of accountability support the web of relationships and responsibilities that define the research enterprise.

The accountability expected of individuals and organizations involved with research may be formally specified in policies or regulations. Accountability under institutional research misconduct policies, for example, could mean that researchers will face reprimand or other corrective actions if they fail to meet their responsibilities.

While responsibilities that are formally defined in policies or regulations are important to accountability in the research enterprise, responsibilities that may not be formally specified should also be included in the concept. For example, senior researchers who supervise others are accountable to their employers and the researchers whom they supervise to conduct themselves as professionals, as this is defined by formal organizational policies. On a less formal level, research supervisors are also accountable for being attentive to the educational and career development needs of students, postdoctoral fellows, and other junior researchers whom they oversee. The same principle holds for individuals working for research institutions, sponsoring organizations, and journals.

The scientific enterprise is filled with professional relationships. Many of them involve judging others’ work for purposes of funding, publication, or deciding who is hired or promoted. Being fair in these contexts means making professional judgments based on appropriate and announced criteria, including processes used to determine outcomes. Fairness in adhering to explicit criteria

and processes reinforces a system in which the core values can operate and trust among the parties can be maintained.

Fairness takes on another dimension in designing criteria and evaluation mechanisms. Research has demonstrated, for example, that grant proposals in which reviewers were blinded to applicant identity and institution receive systematically different funding decisions compared with the outcomes of unblinded reviews ( Ross et al., 2006 ). Truly blinded reviews may be difficult or impossible in a small field. Nevertheless, to the extent possible, the criteria and mechanisms involved in evaluation must be designed so as to ensure against unfair incentive structures or preexisting cultural biases. Fairness is also important in other review contexts, such as the process of peer reviewing articles and the production of book reviews for publication.

Fairness is a particularly important consideration in the list of authors for a publication and in the citations included in reports of research results. Investigators may be tempted to claim that senior or well-known authors played a larger role than they actually did so that their names may help carry the paper to publication and readership. But such a practice is unfair both to the people who actually did the work and to the honorary author, who may not want to be listed prominently or at all. Similarly, nonattribution of credit for contributions to the reported work or careless or negligent crediting of prior work violates the value of fairness. Best practices in authorship, which are based on the value of fairness, honesty, openness, and accountability, are discussed further in Chapter 9 .

Upholding fairness also requires researchers to acknowledge those whose work contributed to their advances. This is usually done through citing relevant work in reporting results. Also, since research is often a highly competitive activity, sometimes there is a race to make a discovery that results in clear winners and losers. Sometimes two groups of researchers make the same discovery nearly simultaneously. Being fair in these situations involves treating research competitors with generosity and magnanimity.

The importance of fairness is also evident in issues involving the duty of care toward human and animal research subjects. Researchers often depend on the use of human and animal subjects for their research, and they have an obligation to treat those subjects fairly—with respect in the case of human subjects and humanely in the case of laboratory animals. They also have obligations to other living things and to those aspects of the environment that affect humans and other living things. These responsibilities need to be balanced and informed by an appreciation for the potential benefits of research.

The research enterprise cannot continue to function unless the members of that system exhibit good stewardship both toward the other members of the system and toward the system itself. Good stewardship implies being aware of

and attending carefully to the dynamics of the relationships within the lab, at the institutional level, and at the broad level of the research enterprise itself. Although we have listed stewardship as the final value in the six we discuss in this report, it supports all the others. Here we take up stewardship within the research enterprise but pause to acknowledge the extension of this value to encompass the larger society.

One area where individual researchers exercise stewardship is by performing service for their institution, discipline, or the broader research enterprise that may not necessarily be recognized or rewarded. These service activities include reviewing, editing, serving on faculty committees, and performing various roles in scientific societies. Senior researchers may also serve as mentors to younger researchers whom they are not directly supervising or formally responsible for. At a broader level, researchers, institutions, sponsors, journals, and societies can contribute to the development and updating of policies and practices affecting research. As will be discussed in Chapter 9 , professional societies perform a valuable service by developing scientific integrity policies for their fields and keeping them updated. Individual journals, journal editors, and member organizations have contributed by developing standards and guidelines in areas such as authorship, data sharing, and the responsibilities of journals when they suspect that submitted work has been fabricated or plagiarized.

Stewardship also involves decisions about support and influences on science. Some aspects of the research system are influenced or determined by outside factors. Public demand, political considerations, concerns about national security, and even the prospects for our species’ survival can inform and influence decisions about the amount of public and private resources devoted to the research enterprise. Such forces also play important roles in determining the balance of resources invested in various fields of study (e.g., both among and within federal agencies), as well as the balance of effort devoted to fundamental versus applied work and the use of various funding mechanisms.

In some cases, good stewardship requires attending to situations in which the broader research enterprise may not be operating optimally. Chapter 6 discusses issues where problems have been identified and are being debated, such as workforce imbalances, the poor career prospects of academic researchers in some fields, and the incentive structures of modern research environments.

Stewardship is particularly evident in the commitment of the research enterprise to education, both of the next generation of researchers and of individuals who do not expect to become scientists. In particular, Chapter 10 discusses the need to educate all members of the research enterprise in the responsible conduct of research. Education is one way in which engaging in science provides benefits both to those within the research system and to the general public outside the system.

A DEFINITION OF RESEARCH INTEGRITY

Making judgments about definitions and terminology as they relate to research integrity and breaches of integrity is a significant component of this committee’s statement of task. Practicing integrity in research means planning, proposing, performing, reporting, and reviewing research in accordance with the values described above. These values should be upheld by research institutions, research sponsors, journals, and learned societies as well as by individual researchers and research groups. General norms and specific research practices that conform to these values have developed over time. Sometimes norms and practices need to be updated as technologies and the institutions that compose the research enterprise evolve. There are also disciplinary differences in some specific research practices, but norms and appropriate practices generally apply across science and engineering research fields. As described more fully in Chapter 9 , best practices in research are those actions undertaken by individuals and organizations that are based on the core values of science and enable good research. They should be embraced, practiced, and promoted.

The integrity of knowledge that emerges from research is based on individual and collective adherence to core values of objectivity, honesty, openness, fairness, accountability, and stewardship. Integrity in science means that the organizations in which research is conducted encourage those involved to exemplify these values in every step of the research process. Understanding the dynamics that support – or distort – practices that uphold the integrity of research by all participants ensures that the research enterprise advances knowledge.

The 1992 report Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process evaluated issues related to scientific responsibility and the conduct of research. It provided a valuable service in describing and analyzing a very complicated set of issues, and has served as a crucial basis for thinking about research integrity for more than two decades. However, as experience has accumulated with various forms of research misconduct, detrimental research practices, and other forms of misconduct, as subsequent empirical research has revealed more about the nature of scientific misconduct, and because technological and social changes have altered the environment in which science is conducted, it is clear that the framework established more than two decades ago needs to be updated.

Responsible Science served as a valuable benchmark to set the context for this most recent analysis and to help guide the committee's thought process. Fostering Integrity in Research identifies best practices in research and recommends practical options for discouraging and addressing research misconduct and detrimental research practices.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2021

Academic integrity at doctoral level: the influence of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic writing

- Jennifer Cutri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5328-5332 1 ,

- Amar Freya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2147-6959 1 ,

- Yeni Karlina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6989-2516 1 ,

- Sweta Vijaykumar Patel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9363-9262 1 ,

- Mehdi Moharami ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6435-8501 1 ,

- Shaoru Zeng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8884-0968 1 ,

- Elham Manzari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2323-5614 1 &

- Lynette Pretorius ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8998-7686 1

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 17 , Article number: 8 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

23 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

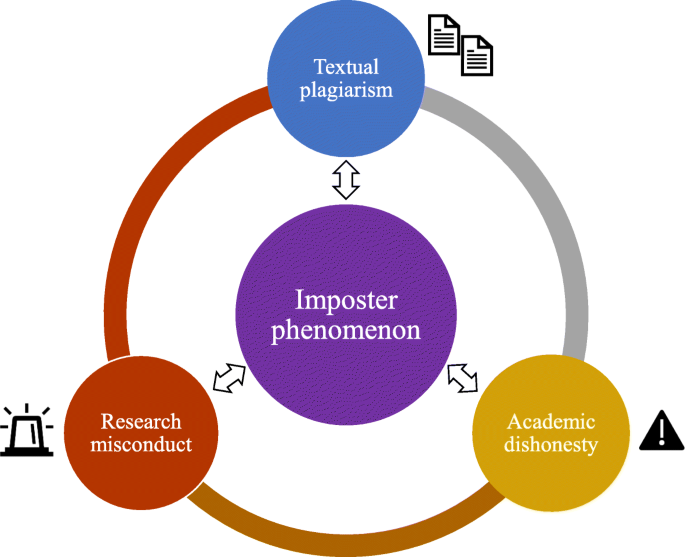

This conceptual review seeks to reframe the view of academic integrity as something to be enforced to an academic skill that needs to be developed. The authors highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. Importantly, this review includes practical suggestions to help educators and higher education institutions support doctoral students’ academic integrity skills. In particular, the authors highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. Therefore, this review argues that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Introduction

In the contemporary higher education environment, issues of academic integrity and credibility are turning matters of learning into matters of surveillance and enforcement. Increasingly, higher education institutions are relying on text-matching software (such as Turnitin) and the monitoring or scrutiny of students (e.g., through practices such as online proctoring) as a proxy to measure their level of academic integrity (Dawson 2021 ). Indeed, failure to adhere to these often contextually and socially constructed rules of academic integrity is termed academic misconduct or dishonesty and can lead to severe consequences for students. As Dawson ( 2021 ) notes, this approach is adversarial, focussing on detection rather than encouraging academic integrity. This adversarial approach is also reflected in recent changes to Australian federal legislation (see the Prohibiting Academic Cheating Services Act 2020 ), with provision of an academic cheating service now attracting criminal or civil penalties. There is also increasing concern about the “ threats to academic integrity [ …] due to the wide-spread growth of commercial essay services and attempts by criminal actors to entice students into deceptive or fraudulent activity” (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) 2021 para. 2 emphasis added). Despite this often adversarial language, however, TEQSA also acknowledges that there is a need to promote academic integrity practices by, for example, working with experts to create an Academic Integrity Toolkit (TEQSA 2021 ).

Interestingly, the higher education environment now appears to lead educators to a dichotomous choice to either be “pro-integrity” or “anti-cheating” (Dawson 2021 p. 3). In this conceptual review, we seek to challenge this perception. We focus on how doctoral education programs can foster academic integrity skills development to create an environment where policies and surveillance strategies are incorporated into pedagogical practice. East ( 2009 ) highlights the importance of viewing academic integrity development as a holistic and aligned approach that supports the development of an honest community within the university. Furthermore, Clarence ( 2020 ) argues that doctoral education is underpinned by the axiological belief that graduates should be confident scholars who value integrity in research, authenticity, and ethics. Therefore, it is our argument that it is the responsibility of educators to explicitly teach these skills as part of doctoral education programs in order to encourage a culture of academic integrity among both staff and students (see, for example, Nayak et al. 2015 ; Richards et al. 2016 ). The long-term benefits of such a culture of academic integrity will include greater awareness of academic integrity for both staff and students, the involvement of students in creating and managing their own academic integrity, a reduction in academic integrity breaches, and improved institutional reputations (Richards et al. 2016 ).

Contextualising our review within the Australian higher education setting, our view of academia is representative of an all-encompassing global space which welcomes the skills, knowledge, values, and practices of all scholars regardless of their background. In this review, we highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. In particular, we explore the impact of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic integrity practices in doctoral education. We conclude this review by providing practical suggestions to help educators and institutions support doctoral student writing in order to avoid forms of unintentional academic misconduct. Therefore, in this review we argue that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Key concepts in academic integrity

As Bretag ( 2016 ) stresses, definitions of integrity terms matter, as researchers have previously fallen into the trap of synonymously linking concepts together. The notion of academic integrity is multifaceted and complex, so defining the concept is an ongoing and contestable debate amongst researchers (Bretag 2016 ). In general, academic integrity is considered the moral code of academia that involves “a commitment to five fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility” (International Center for Academic Integrity 2014 p. 16). Therefore, we consider academic integrity as a researcher’s investment in, and commitment to, the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility in the culture of academia. In this review, we adopt the following interpretation of academic integrity (Exemplary Academic Integrity Project 2013 section 15 para. 2):

Academic integrity means acting with the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility in learning, teaching and research. It is important for students, teachers, researchers and all staff to act in an honest way, be responsible for their actions, and show fairness in every part of their work. Staff should be role models to students. Academic integrity is important for an individual’s and a school’s reputation.

An important component of academic integrity for doctoral students is integrity in the research process. We consider ethical research practice to involve conducting research in a fair, respectful and honest manner, and reporting findings responsibly and honestly.

In contrast, academic misconduct (also termed academic dishonesty) involves behaviours that are contrary to academic integrity, most notably plagiarism, collusion, cheating, and research misconduct. In this review, plagiarism refers to presenting someone else’s published work as your own without appropriate attribution. Drawing on the work of Fatemi and Saito ( 2020 ), we stress that plagiarism can be either intentional or unintentional. We consider intentional plagiarism as purposely using other people’s work and promoting it as your own. In contrast , we define unintentional plagiarism as not acknowledging another researchers’ ideas by, for example, forgetting to insert a reference, not inserting the reference for every sentence from a source, or placing the reference in the wrong place within the text (Fatemi and Saito 2020 ). In this review, collusion is defined as unauthorised collaboration with someone else on assessed tasks while cheating is defined as seeking an unfair advantage in an assessed task, including resubmission of work from another unit. Notably, academic settings have seen a rise in what has been termed contract cheating , where assignments are completed by outside actors in a fee-for-service type arrangement (Bretag et al. 2019 ; Bretag et al. 2020 ; Clarke and Lancaster 2006 ; Dawson 2021 ; Newton 2018 ). Finally, we consider research misconduct to be misrepresenting the study design or methodology, falsifying or fabricating data, and/or breaching ethical research requirements. Academic institutions often have a range of responses, policies, and procedures to identify academic misconduct; these range from official warnings to loss of marks on an assignment or expulsion from the institution for the most severe cases.

Academic integrity and the imposter phenomenon

It is important to note that, for this review, the authors have agreed upon the term imposter phenomenon , although the expression imposter syndrome is often used synonymously in the literature. The term imposter syndrome was initially coined by Clance and Imes ( 1978 ) to describe individuals who felt like frauds and perceived themselves as unworthy of their achievements, despite objective evidence to the contrary. To avoid stigmatisation of these feelings as a pathological syndrome, the term imposter phenomenon is more commonly used in modern thinking. Imposter phenomenon can therefore be defined as “the persistent collection of thoughts, feelings and behaviours that result from the perception of having misrepresented yourself despite objective evidence to the contrary” (Kearns 2015 p. 25).

This notion of feeling like a fraud is frequently experienced by doctoral students. Indeed, half (50.6%) of the PhD students in the study by Van de Velde et al. ( 2019 ) reported experiencing the imposter phenomenon. Similarly, Wilson and Cutri ( 2019 ) revealed how novice academics experienced constant disbelief in their success. This is because the imposter phenomenon is linked to an identity crisis which is commonly experienced by novice academics (Wilson and Cutri 2019 ). For instance, Lau’s ( 2019 ) autoethnographic reflection as a medical doctoral student highlighted how self-imposed pressures during his PhD journey led to feelings of inadequacy. This was due to a prevailing perception of what “the perfect PhD student” was and the feeling that he was not meeting this perceived standard, leading to self-sabotaging behaviours (Lau 2019 p. 52). Thus, from a doctoral student perspective, Lau ( 2019 p. 50) defines the imposter phenomenon as:

feelings of inadequacy experienced by those within academia that indicate a fear of being exposed as a fraud. These feelings are not ascribed to external measures of competence or success (e.g., publishing papers or winning prizes), but internal feelings of not being good enough for their chosen role (e.g., being a PhD student or academic staff member).

Lau ( 2019 ) warns that, if these feelings are left unchecked, it could lead to low self-confidence and high anxiety.

The imposter phenomenon is increasingly recognised as a significant issue by higher education institutions, but this is often considered a mental health concern affecting productivity and success (see, for example, University of Cambridge 2021 ; University of Waterloo 2021 ). It is important to note, though, that the feelings of fraudulence and negative self-confidence can be attributed to the socio-political and cultural environment of academia in which doctoral students are immersed. As Hutchins ( 2015 ) notes, the imposter phenomenon thrives in environments where there are expectations of perfectionism, highly competitive work cultures, and stressful environments. Academia is a high-stakes, competitive environment where a person’s success is measured by the quantity and quality of their research output, commonly referred to as an environment of publish or perish . Indeed, Moosa ( 2018 ) notes that academics must obey the rules of the publish or perish environment if they are to progress through their career. With an emphasis on scholarly dissemination, doctoral students are thrown into a new context of public critique through the peer review and publication process. While this is an opportunity for academics to showcase their research, Parkman ( 2016 ) notes that such public scrutiny invokes the common imposter phenomenon fear of being found out as a fraud. This is because doctoral candidates are constantly exposed to the final product, while the process of writing has been devalued (Wilson and Cutri 2019 ). The doctoral journey, however, should be about the process , as candidates are developing their skills and building their academic identities as future researchers in their fields.

When academic institutions focus on polished products, doctoral students who are currently engaged in the writing process feel a sense they are not good enough (Wilson and Cutri 2019 ). This is because the writing process and expectations at doctoral level are complex and challenging, requiring students to develop specific academic skill sets that are different from their previous studies (see Level 10 of the Australian Qualifications Framework for a list of the expected skills of doctoral graduates in Australia, Australian Qualifications Framework Council 2013 ). Facing these new challenges can be overwhelming and students compensate by engaging in sabotaging behaviours (such as procrastination, perfectionism, or avoidance) because they feel they must write like the experts in their field. Cisco ( 2020a ) found that imposter phenomenon feelings became more prevalent with the challenge of these new and more complex academic tasks. This struggle during the reading and writing process can be attributed to a need for further development of the necessary academic literacy skills for a specific discipline. In this review, we consider literacy to refer to the socially constructed use of language within a particular context (Barton and Hamilton 2012 ; Lea 2004 ; Lea and Street 1998 , 2006 ; Street 1984 , 1994 ). Consequently, it is important to note that literacy is continuously constructed and includes elements of both power and privilege (Lea 2004 ; Lea and Street 1998 , 2006 ). The term academic literacy skills , therefore, reflect a broad range of practices that are involved in the practice of communicating scholarly research (for example, learning the differences in academic writing for literature reviews, methodology, data analysis, and discussion of findings sections to answer the all-important so what question). These more advanced academic literacy skills are relatively new aspects for doctoral students, as the production of new knowledge is what makes a PhD candidature unique.