- Privacy Policy

Home » Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Background of The Study

Definition:

Background of the study refers to the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being studied. It provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and the significance of the study.

The background of the study usually includes a discussion of the relevant literature, the gap in knowledge or understanding, and the research questions or hypotheses to be addressed. It also highlights the importance of the research topic and its potential contributions to the field. A well-written background of the study sets the stage for the research and helps the reader to appreciate the need for the study and its potential significance.

How to Write Background of The Study

Here are some steps to help you write the background of the study:

Identify the Research Problem

Start by identifying the research problem you are trying to address. This problem should be significant and relevant to your field of study.

Provide Context

Once you have identified the research problem, provide some context. This could include the historical, social, or political context of the problem.

Review Literature

Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the topic. This will help you understand what has been studied and what gaps exist in the current research.

Identify Research Gap

Based on your literature review, identify the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research aims to address. This gap will be the focus of your research question or hypothesis.

State Objectives

Clearly state the objectives of your research . These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Discuss Significance

Explain the significance of your research. This could include its potential impact on theory , practice, policy, or society.

Finally, summarize the key points of the background of the study. This will help the reader understand the research problem, its context, and its significance.

How to Write Background of The Study in Proposal

The background of the study is an essential part of any proposal as it sets the stage for the research project and provides the context and justification for why the research is needed. Here are the steps to write a compelling background of the study in your proposal:

- Identify the problem: Clearly state the research problem or gap in the current knowledge that you intend to address through your research.

- Provide context: Provide a brief overview of the research area and highlight its significance in the field.

- Review literature: Summarize the relevant literature related to the research problem and provide a critical evaluation of the current state of knowledge.

- Identify gaps : Identify the gaps or limitations in the existing literature and explain how your research will contribute to filling these gaps.

- Justify the study : Explain why your research is important and what practical or theoretical contributions it can make to the field.

- Highlight objectives: Clearly state the objectives of the study and how they relate to the research problem.

- Discuss methodology: Provide an overview of the methodology you will use to collect and analyze data, and explain why it is appropriate for the research problem.

- Conclude : Summarize the key points of the background of the study and explain how they support your research proposal.

How to Write Background of The Study In Thesis

The background of the study is a critical component of a thesis as it provides context for the research problem, rationale for conducting the study, and the significance of the research. Here are some steps to help you write a strong background of the study:

- Identify the research problem : Start by identifying the research problem that your thesis is addressing. What is the issue that you are trying to solve or explore? Be specific and concise in your problem statement.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the relevant literature on the topic. This should include scholarly articles, books, and other sources that are directly related to your research question.

- I dentify gaps in the literature: After reviewing the literature, identify any gaps in the existing research. What questions remain unanswered? What areas have not been explored? This will help you to establish the need for your research.

- Establish the significance of the research: Clearly state the significance of your research. Why is it important to address this research problem? What are the potential implications of your research? How will it contribute to the field?

- Provide an overview of the research design: Provide an overview of the research design and methodology that you will be using in your study. This should include a brief explanation of the research approach, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- State the research objectives and research questions: Clearly state the research objectives and research questions that your study aims to answer. These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Summarize the chapter: Summarize the chapter by highlighting the key points and linking them back to the research problem, significance of the study, and research questions.

How to Write Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are the steps to write the background of the study in a research paper:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the research problem that your study aims to address. This can be a particular issue, a gap in the literature, or a need for further investigation.

- Conduct a literature review: Conduct a thorough literature review to gather information on the topic, identify existing studies, and understand the current state of research. This will help you identify the gap in the literature that your study aims to fill.

- Explain the significance of the study: Explain why your study is important and why it is necessary. This can include the potential impact on the field, the importance to society, or the need to address a particular issue.

- Provide context: Provide context for the research problem by discussing the broader social, economic, or political context that the study is situated in. This can help the reader understand the relevance of the study and its potential implications.

- State the research questions and objectives: State the research questions and objectives that your study aims to address. This will help the reader understand the scope of the study and its purpose.

- Summarize the methodology : Briefly summarize the methodology you used to conduct the study, including the data collection and analysis methods. This can help the reader understand how the study was conducted and its reliability.

Examples of Background of The Study

Here are some examples of the background of the study:

Problem : The prevalence of obesity among children in the United States has reached alarming levels, with nearly one in five children classified as obese.

Significance : Obesity in childhood is associated with numerous negative health outcomes, including increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers.

Gap in knowledge : Despite efforts to address the obesity epidemic, rates continue to rise. There is a need for effective interventions that target the unique needs of children and their families.

Problem : The use of antibiotics in agriculture has contributed to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which poses a significant threat to human health.

Significance : Antibiotic-resistant infections are responsible for thousands of deaths each year and are a major public health concern.

Gap in knowledge: While there is a growing body of research on the use of antibiotics in agriculture, there is still much to be learned about the mechanisms of resistance and the most effective strategies for reducing antibiotic use.

Edxample 3:

Problem : Many low-income communities lack access to healthy food options, leading to high rates of food insecurity and diet-related diseases.

Significance : Poor nutrition is a major contributor to chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Gap in knowledge : While there have been efforts to address food insecurity, there is a need for more research on the barriers to accessing healthy food in low-income communities and effective strategies for increasing access.

Examples of Background of The Study In Research

Here are some real-life examples of how the background of the study can be written in different fields of study:

Example 1 : “There has been a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes in recent years. This has led to an increased demand for effective diabetes management strategies. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a new diabetes management program in improving patient outcomes.”

Example 2 : “The use of social media has become increasingly prevalent in modern society. Despite its popularity, little is known about the effects of social media use on mental health. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health in young adults.”

Example 3: “Despite significant advancements in cancer treatment, the survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer remains low. The purpose of this study is to identify potential biomarkers that can be used to improve early detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Proposal

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in a proposal:

Example 1 : The prevalence of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade. This study aims to investigate the causes and impacts of mental health issues on academic performance and wellbeing.

Example 2 : Climate change is a global issue that has significant implications for agriculture in developing countries. This study aims to examine the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change and identify effective strategies to enhance their resilience.

Example 3 : The use of social media in political campaigns has become increasingly common in recent years. This study aims to analyze the effectiveness of social media campaigns in mobilizing young voters and influencing their voting behavior.

Example 4 : Employee turnover is a major challenge for organizations, especially in the service sector. This study aims to identify the key factors that influence employee turnover in the hospitality industry and explore effective strategies for reducing turnover rates.

Examples of Background of The Study in Thesis

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in the thesis:

Example 1 : “Women’s participation in the workforce has increased significantly over the past few decades. However, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership positions, particularly in male-dominated industries such as technology. This study aims to examine the factors that contribute to the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in the technology industry, with a focus on organizational culture and gender bias.”

Example 2 : “Mental health is a critical component of overall health and well-being. Despite increased awareness of the importance of mental health, there are still significant gaps in access to mental health services, particularly in low-income and rural communities. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based mental health intervention in improving mental health outcomes in underserved populations.”

Example 3: “The use of technology in education has become increasingly widespread, with many schools adopting online learning platforms and digital resources. However, there is limited research on the impact of technology on student learning outcomes and engagement. This study aims to explore the relationship between technology use and academic achievement among middle school students, as well as the factors that mediate this relationship.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are some examples of how the background of the study can be written in various fields:

Example 1: The prevalence of obesity has been on the rise globally, with the World Health Organization reporting that approximately 650 million adults were obese in 2016. Obesity is a major risk factor for several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. In recent years, several interventions have been proposed to address this issue, including lifestyle changes, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. However, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective intervention for obesity management. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of different interventions for obesity management and identify the most effective one.

Example 2: Antibiotic resistance has become a major public health threat worldwide. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are associated with longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality. The inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the main factors contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance. Despite numerous efforts to promote the rational use of antibiotics, studies have shown that many healthcare providers continue to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately. This study aims to explore the factors influencing healthcare providers’ prescribing behavior and identify strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing practices.

Example 3: Social media has become an integral part of modern communication, with millions of people worldwide using platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Social media has several advantages, including facilitating communication, connecting people, and disseminating information. However, social media use has also been associated with several negative outcomes, including cyberbullying, addiction, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on mental health and identify the factors that mediate this relationship.

Purpose of Background of The Study

The primary purpose of the background of the study is to help the reader understand the rationale for the research by presenting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem.

More specifically, the background of the study aims to:

- Provide a clear understanding of the research problem and its context.

- Identify the gap in knowledge that the study intends to fill.

- Establish the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field.

- Highlight the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

- Provide a rationale for the research questions or hypotheses and the research design.

- Identify the limitations and scope of the study.

When to Write Background of The Study

The background of the study should be written early on in the research process, ideally before the research design is finalized and data collection begins. This allows the researcher to clearly articulate the rationale for the study and establish a strong foundation for the research.

The background of the study typically comes after the introduction but before the literature review section. It should provide an overview of the research problem and its context, and also introduce the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

Writing the background of the study early on in the research process also helps to identify potential gaps in knowledge and areas for further investigation, which can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design. By establishing the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field, the background of the study can also help to justify the research and secure funding or support from stakeholders.

Advantage of Background of The Study

The background of the study has several advantages, including:

- Provides context: The background of the study provides context for the research problem by highlighting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem. This allows the reader to understand the research problem in its broader context and appreciate its significance.

- Identifies gaps in knowledge: By reviewing the existing literature related to the research problem, the background of the study can identify gaps in knowledge that the study intends to fill. This helps to establish the novelty and originality of the research and its potential contribution to the field.

- Justifies the research : The background of the study helps to justify the research by demonstrating its significance and potential impact. This can be useful in securing funding or support for the research.

- Guides the research design: The background of the study can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design by identifying key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem. This ensures that the research is grounded in existing knowledge and is designed to address the research problem effectively.

- Establishes credibility: By demonstrating the researcher’s knowledge of the field and the research problem, the background of the study can establish the researcher’s credibility and expertise, which can enhance the trustworthiness and validity of the research.

Disadvantages of Background of The Study

Some Disadvantages of Background of The Study are as follows:

- Time-consuming : Writing a comprehensive background of the study can be time-consuming, especially if the research problem is complex and multifaceted. This can delay the research process and impact the timeline for completing the study.

- Repetitive: The background of the study can sometimes be repetitive, as it often involves summarizing existing research and theories related to the research problem. This can be tedious for the reader and may make the section less engaging.

- Limitations of existing research: The background of the study can reveal the limitations of existing research related to the problem. This can create challenges for the researcher in developing research questions or hypotheses that address the gaps in knowledge identified in the background of the study.

- Bias : The researcher’s biases and perspectives can influence the content and tone of the background of the study. This can impact the reader’s perception of the research problem and may influence the validity of the research.

- Accessibility: Accessing and reviewing the literature related to the research problem can be challenging, especially if the researcher does not have access to a comprehensive database or if the literature is not available in the researcher’s language. This can limit the depth and scope of the background of the study.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Problem Statement – Writing Guide, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

- UConn Library

- Research Now

- Get Started

- Background Research

Get Started — Background Research

- Reading (and Understanding) Your Assignment

- Initial Searching

- Forming a Research Question

- Help & Other Resources

- Research Now Homepage

What's Happening When You Do Background Research?

When you do background research, you're exploring your general area of interest so that you can form a more focused topic. You will be making an entry into an ongoing conversation, and you have the opportunity to ask new questions and create new knowledge.

Why is this important?

Have you ever done a project that just never seemed to come together?

"I had a general idea but not a specific focus. As I was writing, I didn't know what my focus was. When I was finished, I didn't know what my focus was. My teacher says she doesn't know what my focus was. I don't think I ever acquired a focus. It was an impossible paper to write. I would just sit there and say, "I'm stuck." If I learned anything from that paper it is, you have to have a focus. You have to have something to center on. You can't just have a topic. You should have an idea when you start. I had a topic but I didn't know what I wanted to do with it. I figured that when I did my research it would focus in. But I didn't let it. I kept saying, 'this is interesting and this is interesting and I'll just smush it all together.' It didn't work out." - ( Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century )

Can you relate?

Doing background research to explore your initial topic can help you to find create a focused research question . Another benefit to background searching - it's very hard to write about something if you don't know anything about it! At this point, collecting ideas to help you construct your focused topic will be very helpful. Not every idea you encounter will find its way into your final project, so don't worry about collecting very, very detailed information just yet. Wait until your project has found a focus.

While you're doing you're background research, don't be surprised if your topic changes in unexpected ways - you're discovering more about your topic, and you're making choices based on on the new information you find. If your topic changes, that's OK!

- Research Log This research log is a tool to help you throughout your project. Logging your research and making a general record of the sources you find will be very useful for you at this stage.

Strategies for Background Research

- What Interests You?

- What Am I Looking For?

- Take Notes While Searching

Identifying what interests you in the context of your assignment can help you get started on your research project.

Some questions to consider:

Why is your project interesting/important to you? To your community? To the world?

What about your project sparks your curiosity and creativity?

Some ideas from the Reference Librarians at Gustavus Adolphus

- Make a list of possible issues to research. Use class discussions, texts, personal interests, conversations with friends, and discussions with your teacher for ideas. Start writing them down - you'd be surprised how much faster they come once you start writing.

- Map out the topic by finding out what others have had to say about it. This is not the time for in-depth reading, but rather for a quick scan. Many students start with a Google search, but you can also browse the shelves where books on the topic are kept and see what controversies or issues have been receiving attention. Search a database for articles on your topic area and sort out the various approaches writers have taken. Look for overviews and surveys of the topic that put the various schools of thought or approaches in context. You may start out knowing virtually nothing about your topic, but after scanning what's out there you should have several ideas worth following up.

- Invent questions. Do two things you come across seem to offer interesting contrasts? Does one thing seem intriguingly connected to something else? Is there something about the topic that surprises you? Do you encounter anything that makes you wonder why? Do you run into something that makes you think, "no way! That can't be right." Chances are you've just uncovered a good research focus.

- Draft a proposal for research. Sometimes a teacher will ask you for a formal written proposal. Even if it isn’t required, it can be a useful exercise. Write down what you want to do, how you plan to do it, and why it's important. You may well change your topic entirely by the time its finished, but writing down where you plan to take your research at this stage can help you clarify your thoughts and plan your next steps.

- Source: The Reference Librarians at Gustavus Adolphus College

- Gustavus Adolphus College: Doing Research

It can be very helpful to write out your thoughts as you work through the answers to these questions.

Think about what you need to know:

- What do you already know about your topic?

- What don't you know about your topic? What do you feel like you might need to know?

- What are the fundamental facts and background on your topic? What do you need to know to write knowledgeably about your topic?

- What are the different viewpoints on your topic? You should expect to encounter diverse views on a topic.

And of course...

- What is your assignment asking of you?

When you are doing your research, you are not looking for one perfect source with one right answer. You're collecting and thinking critically about ideas to form a focus for your own research.

If you're having trouble answering these questions, you might find the six journalist's questions helpful in focusing your thinking:

Don't feel like you need to get bogged down in the minutiae of every source at this point!

At this point in your research, you are browsing for ideas and information to help you fill in the gaps. You're looking to develop a more focused topic. When you focus your topic you'll be able to really engage with the sources that will help you with your sources.

Not quite sure how to get started? The KWHL Tool will help you visualize your thinking, and start organizing the information you find. It will help you sort out

- What you already know

- What you don’t yet know about your topic

- Where you’re looking ( how will you find it)

- What you’ve learned

All of which will help you focus your project (and maybe save a little time & stress, too!).

- KWHL Chart Use this chart to help organize your project

- KWHL Chart PDF version of the KWHL Chart to help organize your project

As you're doing your research, take some brief notes about the sources you've found. Noting interesting ideas and items will help you remember what you've read as you put your ideas together to form a research question. It will also help you to make note of parts of your sources that you want to quote later (and find it easily while you're putting your research project together!).

- Stop 'N Jot This tool will help you keep track of good ideas and questions as you do your preliminary research.

- << Previous: Reading (and Understanding) Your Assignment

- Next: Initial Searching >>

- Last Updated: Aug 2, 2024 4:30 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/getstarted

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

Aspect | Background | Introduction |

Primary purpose | Provides context and logical reasons for the research, explaining why the study is necessary. | Entails the broader scope of the research, hinting at its objectives and significance. |

Depth of information | It delves into the existing literature, highlighting gaps or unresolved questions that the research aims to address. | It offers a general overview, touching upon the research topic without going into extensive detail. |

Content focus | The focus is on historical context, previous studies, and the evolution of the research topic. | The focus is on the broader research field, potential implications, and a preview of the research structure. |

Position in a research paper | Typically comes at the very beginning, setting the stage for the research. | Follows the background, leading readers into the main body of the research. |

Tone | Analytical, detailing the topic and its significance. | General and anticipatory, preparing readers for the depth and direction of the focus of the study. |

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

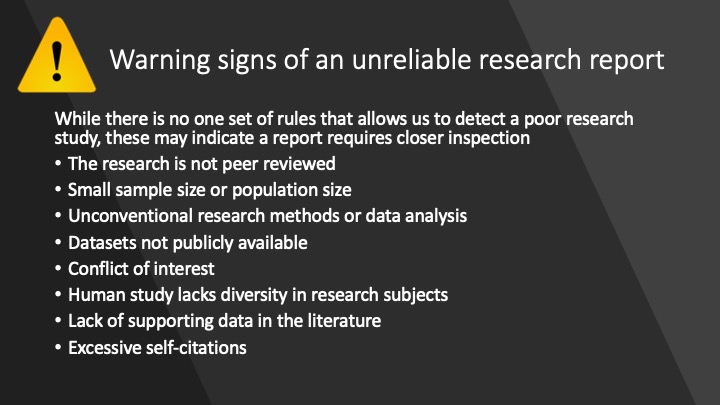

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Background Information

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Background information identifies and describes the history and nature of a well-defined research problem with reference to contextualizing existing literature. The background information should indicate the root of the problem being studied, appropriate context of the problem in relation to theory, research, and/or practice , its scope, and the extent to which previous studies have successfully investigated the problem, noting, in particular, where gaps exist that your study attempts to address. Background information does not replace the literature review section of a research paper; it is intended to place the research problem within a specific context and an established plan for its solution.

Fitterling, Lori. Researching and Writing an Effective Background Section of a Research Paper. Kansas City University of Medicine & Biosciences; Creating a Research Paper: How to Write the Background to a Study. DurousseauElectricalInstitute.com; Background Information: Definition of Background Information. Literary Devices Definition and Examples of Literary Terms.

Importance of Having Enough Background Information

Background information expands upon the key points stated in the beginning of your introduction but is not intended to be the main focus of the paper. It generally supports the question, what is the most important information the reader needs to understand before continuing to read the paper? Sufficient background information helps the reader determine if you have a basic understanding of the research problem being investigated and promotes confidence in the overall quality of your analysis and findings. This information provides the reader with the essential context needed to conceptualize the research problem and its significance before moving on to a more thorough analysis of prior research.

Forms of contextualization included in background information can include describing one or more of the following:

- Cultural -- placed within the learned behavior of a specific group or groups of people.

- Economic -- of or relating to systems of production and management of material wealth and/or business activities.

- Gender -- located within the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with being self-identified as male, female, or other form of gender expression.

- Historical -- the time in which something takes place or was created and how the condition of time influences how you interpret it.

- Interdisciplinary -- explanation of theories, concepts, ideas, or methodologies borrowed from other disciplines applied to the research problem rooted in a discipline other than the discipline where your paper resides.

- Philosophical -- clarification of the essential nature of being or of phenomena as it relates to the research problem.

- Physical/Spatial -- reflects the meaning of space around something and how that influences how it is understood.

- Political -- concerns the environment in which something is produced indicating it's public purpose or agenda.

- Social -- the environment of people that surrounds something's creation or intended audience, reflecting how the people associated with something use and interpret it.

- Temporal -- reflects issues or events of, relating to, or limited by time. Concerns past, present, or future contextualization and not just a historical past.

Background information can also include summaries of important research studies . This can be a particularly important element of providing background information if an innovative or groundbreaking study about the research problem laid a foundation for further research or there was a key study that is essential to understanding your arguments. The priority is to summarize for the reader what is known about the research problem before you conduct the analysis of prior research. This is accomplished with a general summary of the foundational research literature [with citations] that document findings that inform your study's overall aims and objectives.

NOTE: Research studies cited as part of the background information of your introduction should not include very specific, lengthy explanations. This should be discussed in greater detail in your literature review section. If you find a study requiring lengthy explanation, consider moving it to the literature review section.

ANOTHER NOTE: In some cases, your paper's introduction only needs to introduce the research problem, explain its significance, and then describe a road map for how you are going to address the problem; the background information basically forms the introduction part of your literature review. That said, while providing background information is not required, including it in the introduction is a way to highlight important contextual information that could otherwise be hidden or overlooked by the reader if placed in the literature review section.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: In some research studies, the background information is described in a separate section after the introduction and before the literature review. This is most often done if the topic is especially complex or requires a lot of context in order to fully grasp the significance of the research problem. Most college-level research papers do not require this unless required by your professor. However, if you find yourself needing to write more than a couple of pages [double-spaced lines] to provide the background information, it can be written as a separate section to ensure the introduction is not too lengthy.

Background of the Problem Section: What do you Need to Consider? Anonymous. Harvard University; Hopkins, Will G. How to Write a Research Paper. SPORTSCIENCE, Perspectives/Research Resources. Department of Physiology and School of Physical Education, University of Otago, 1999; Green, L. H. How to Write the Background/Introduction Section. Physics 499 Powerpoint slides. University of Illinois; Pyrczak, Fred. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 8th edition. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2014; Stevens, Kathleen C. “Can We Improve Reading by Teaching Background Information?.” Journal of Reading 25 (January 1982): 326-329; Woodall, W. Gill. Writing the Background and Significance Section. Senior Research Scientist and Professor of Communication. Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions. University of New Mexico.

Structure and Writing Style

Providing background information in the introduction of a research paper serves as a bridge that links the reader to the research problem . Precisely how long and in-depth this bridge should be is largely dependent upon how much information you think the reader will need to know in order to fully understand the problem being discussed and to appreciate why the issues you are investigating are important.

From another perspective, the length and detail of background information also depends on the degree to which you need to demonstrate to your professor how much you understand the research problem. Keep this in mind because providing pertinent background information can be an effective way to demonstrate that you have a clear grasp of key issues, debates, and concepts related to your overall study.

The structure and writing style of your background information can vary depending upon the complexity of your research and/or the nature of the assignment. However, in most cases it should be limited to only one to two paragraphs in your introduction.

Given this, here are some questions to consider while writing this part of your introduction :

- Are there concepts, terms, theories, or ideas that may be unfamiliar to the reader and, thus, require additional explanation?

- Are there historical elements that need to be explored in order to provide needed context, to highlight specific people, issues, or events, or to lay a foundation for understanding the emergence of a current issue or event?

- Are there theories, concepts, or ideas borrowed from other disciplines or academic traditions that may be unfamiliar to the reader and therefore require further explanation?

- Is there a key study or small set of studies that set the stage for understanding the topic and frames why it is important to conduct further research on the topic?

- Y our study uses a method of analysis never applied before;

- Your study investigates a very esoteric or complex research problem;

- Your study introduces new or unique variables that need to be taken into account ; or,

- Your study relies upon analyzing unique texts or documents, such as, archival materials or primary documents like diaries or personal letters that do not represent the established body of source literature on the topic?

Almost all introductions to a research problem require some contextualizing, but the scope and breadth of background information varies depending on your assumption about the reader's level of prior knowledge . However, despite this assessment, background information should be brief and succinct and sets the stage for the elaboration of critical points or in-depth discussion of key issues in the literature review section of your paper.

Writing Tip

Background Information vs. the Literature Review

Incorporating background information into the introduction is intended to provide the reader with critical information about the topic being studied, such as, highlighting and expanding upon foundational studies conducted in the past, describing important historical events that inform why and in what ways the research problem exists, defining key components of your study [concepts, people, places, phenomena] and/or placing the research problem within a particular context. Although introductory background information can often blend into the literature review portion of the paper, essential background information should not be considered a substitute for a comprehensive review and synthesis of relevant research literature.

Hart, Cris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998; Pyrczak, Fred. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 8th edition. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2014.

- << Previous: The C.A.R.S. Model

- Next: The Research Problem/Question >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

- Gale Ebooks This link opens in a new window Gale Ebooks (formerly named Gale Virtual Library or GVRL) provides a wealth of full-text reference and general subject books in a wide variety of subjects. more... less... Sources offered in the GVRL include multi-volume encyclopedias, biographical collections, business plan handbooks, company histories, consumer health references and history compilations. A wide variety of subjects are covered including arts, biography, business, education, environment, history, law, medicine, multicultural, religion and science.

- Oxford Bibliographies This link opens in a new window Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides across a variety of subject areas. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource directs researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

If you can't find an encyclopedia, dictionary or textbook article on your topic, try using broader keywords or ask a librarian for help. For example, if your topic is "global warming," con sider searching for an encyclopedia on the environment.

Finding background information

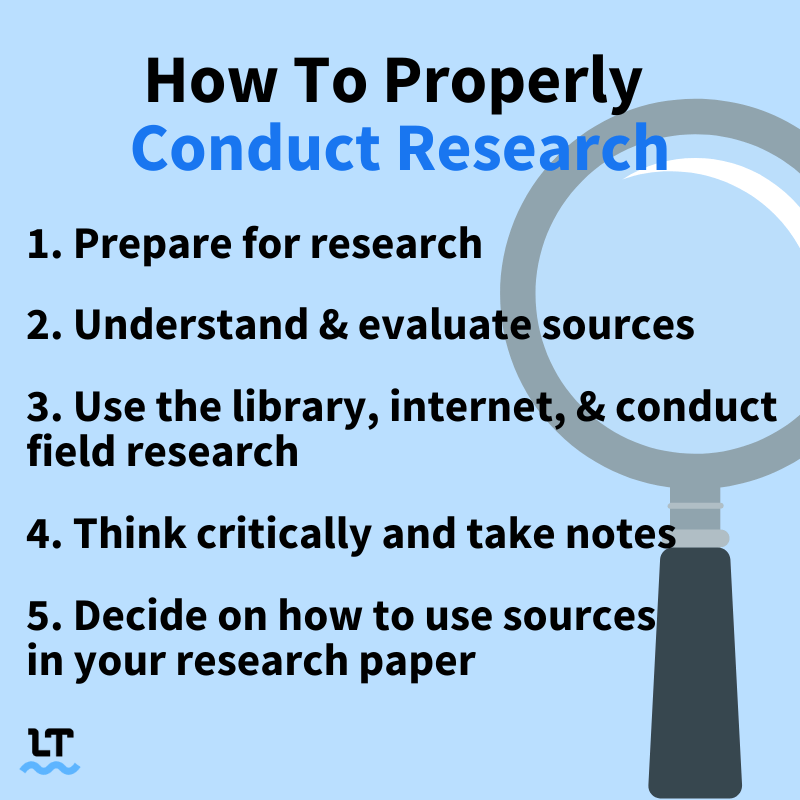

Once you have identified keywords, the next step is to find background information on your topic.

Background information serves many purposes:

- If you are unfamiliar with the topic, it provides a good overview of the subject matter.

- It helps you to identify important facts related to your topic such as terminology, dates, events, history, and relevant names or organizations.

- It can help you refine your topic.

- Background research might lead you to bibliographies that you can use to find additional sources of information.

Background information can be found in:

- dictionaries

- general encyclopedias

- subject-specific encyclopedias

- article databases

These sources are often listed on the "Find Resources" tab of our research by subject guides. You can browse a complete list of the Library's guides by visiting the "Research by Subject" homepage.

- << Previous: Identify Keywords

- Next: Develop Research Questions >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

What Is Background in a Research Paper?

So you have carefully written your research paper and probably ran it through your colleagues ten to fifteen times. While there are many elements to a good research article, one of the most important elements for your readers is the background of your study.

What is Background of the Study in Research

The background of your study will provide context to the information discussed throughout the research paper . Background information may include both important and relevant studies. This is particularly important if a study either supports or refutes your thesis.

Why is Background of the Study Necessary in Research?

The background of the study discusses your problem statement, rationale, and research questions. It links introduction to your research topic and ensures a logical flow of ideas. Thus, it helps readers understand your reasons for conducting the study.

Providing Background Information

The reader should be able to understand your topic and its importance. The length and detail of your background also depend on the degree to which you need to demonstrate your understanding of the topic. Paying close attention to the following questions will help you in writing background information:

- Are there any theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may be unfamiliar to the target audience and will require you to provide any additional explanation?

- Any historical data that need to be shared in order to provide context on why the current issue emerged?

- Are there any concepts that may have been borrowed from other disciplines that may be unfamiliar to the reader and need an explanation?

Related: Ready with the background and searching for more information on journal ranking? Check this infographic on the SCImago Journal Rank today!

Is the research study unique for which additional explanation is needed? For instance, you may have used a completely new method

How to Write a Background of the Study

The structure of a background study in a research paper generally follows a logical sequence to provide context, justification, and an understanding of the research problem. It includes an introduction, general background, literature review , rationale , objectives, scope and limitations , significance of the study and the research hypothesis . Following the structure can provide a comprehensive and well-organized background for your research.

Here are the steps to effectively write a background of the study.

1. Identify Your Audience:

Determine the level of expertise of your target audience. Tailor the depth and complexity of your background information accordingly.

2. Understand the Research Problem:

Define the research problem or question your study aims to address. Identify the significance of the problem within the broader context of the field.

3. Review Existing Literature:

Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known in the area. Summarize key findings, theories, and concepts relevant to your research.

4. Include Historical Data:

Integrate historical data if relevant to the research, as current issues often trace back to historical events.

5. Identify Controversies and Gaps:

Note any controversies or debates within the existing literature. Identify gaps , limitations, or unanswered questions that your research can address.

6. Select Key Components:

Choose the most critical elements to include in the background based on their relevance to your research problem. Prioritize information that helps build a strong foundation for your study.

7. Craft a Logical Flow:

Organize the background information in a logical sequence. Start with general context, move to specific theories and concepts, and then focus on the specific problem.

8. Highlight the Novelty of Your Research:

Clearly explain the unique aspects or contributions of your study. Emphasize why your research is different from or builds upon existing work.

Here are some extra tips to increase the quality of your research background:

Example of a Research Background

Here is an example of a research background to help you understand better.

The above hypothetical example provides a research background, addresses the gap and highlights the potential outcome of the study; thereby aiding a better understanding of the proposed research.

What Makes the Introduction Different from the Background?

Your introduction is different from your background in a number of ways.

- The introduction contains preliminary data about your topic that the reader will most likely read , whereas the background clarifies the importance of the paper.

- The background of your study discusses in depth about the topic, whereas the introduction only gives an overview.

- The introduction should end with your research questions, aims, and objectives, whereas your background should not (except in some cases where your background is integrated into your introduction). For instance, the C.A.R.S. ( Creating a Research Space ) model, created by John Swales is based on his analysis of journal articles. This model attempts to explain and describe the organizational pattern of writing the introduction in social sciences.

Points to Note

Your background should begin with defining a topic and audience. It is important that you identify which topic you need to review and what your audience already knows about the topic. You should proceed by searching and researching the relevant literature. In this case, it is advisable to keep track of the search terms you used and the articles that you downloaded. It is helpful to use one of the research paper management systems such as Papers, Mendeley, Evernote, or Sente. Next, it is helpful to take notes while reading. Be careful when copying quotes verbatim and make sure to put them in quotation marks and cite the sources. In addition, you should keep your background focused but balanced enough so that it is relevant to a broader audience. Aside from these, your background should be critical, consistent, and logically structured.

Writing the background of your study should not be an overly daunting task. Many guides that can help you organize your thoughts as you write the background. The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to your research topic and should be done with strong knowledge and thoughtful writing.

The background of a research paper typically ranges from one to two paragraphs, summarizing the relevant literature and context of the study. It should be concise, providing enough information to contextualize the research problem and justify the need for the study. Journal instructions about any word count limits should be kept in mind while deciding on the length of the final content.

The background of a research paper provides the context and relevant literature to understand the research problem, while the introduction also introduces the specific research topic, states the research objectives, and outlines the scope of the study. The background focuses on the broader context, whereas the introduction focuses on the specific research project and its objectives.

When writing the background for a study, start by providing a brief overview of the research topic and its significance in the field. Then, highlight the gaps in existing knowledge or unresolved issues that the study aims to address. Finally, summarize the key findings from relevant literature to establish the context and rationale for conducting the research, emphasizing the need and importance of the study within the broader academic landscape.

The background in a research paper is crucial as it sets the stage for the study by providing essential context and rationale. It helps readers understand the significance of the research problem and its relevance in the broader field. By presenting relevant literature and highlighting gaps, the background justifies the need for the study, building a strong foundation for the research and enhancing its credibility.

The presentation very informative

It is really educative. I love the workshop. It really motivated me into writing my first paper for publication.

an interesting clue here, thanks.

thanks for the answers.

Good and interesting explanation. Thanks

Thank you for good presentation.

Hi Adam, we are glad to know that you found our article beneficial

The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to YOUR research topic.

Awesome. Exactly what i was looking forwards to 😉

Hi Maryam, we are glad to know that you found our resource useful.

my understanding of ‘Background of study’ has been elevated.

Hi Peter, we are glad to know that our article has helped you get a better understanding of the background in a research paper.

thanks to give advanced information

Hi Shimelis, we are glad to know that you found the information in our article beneficial.

When i was studying it is very much hard for me to conduct a research study and know the background because my teacher in practical research is having a research so i make it now so that i will done my research

Very informative……….Thank you.

The confusion i had before, regarding an introduction and background to a research work is now a thing of the past. Thank you so much.

Thanks for your help…

Thanks for your kind information about the background of a research paper.

Thanks for the answer

Very informative. I liked even more when the difference between background and introduction was given. I am looking forward to learning more from this site. I am in Botswana

Hello, I am Benoît from Central African Republic. Right now I am writing down my research paper in order to get my master degree in British Literature. Thank you very much for posting all this information about the background of the study. I really appreciate. Thanks!

The write up is quite good, detailed and informative. Thanks a lot. The article has certainly enhanced my understanding of the topic.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer-Review Week 2023

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

Writing Research Background

Research background is a brief outline of the most important studies that have been conducted so far presented in a chronological order. Research background part in introduction chapter can be also headed ‘Background of the Study.” Research background should also include a brief discussion of major theories and models related to the research problem.

Specifically, when writing research background you can discuss major theories and models related to your research problem in a chronological order to outline historical developments in the research area. When writing research background, you also need to demonstrate how your research relates to what has been done so far in the research area.

Research background is written after the literature review. Therefore, literature review has to be the first and the longest stage in the research process, even before the formulation of research aims and objectives, right after the selection of the research area. Once the research area is selected, the literature review is commenced in order to identify gaps in the research area.

Research aims and objectives need to be closely associated with the elimination of this gap in the literature. The main difference between background of the study and literature review is that the former only provides general information about what has been done so far in the research area, whereas the latter elaborates and critically reviews previous works.

John Dudovskiy

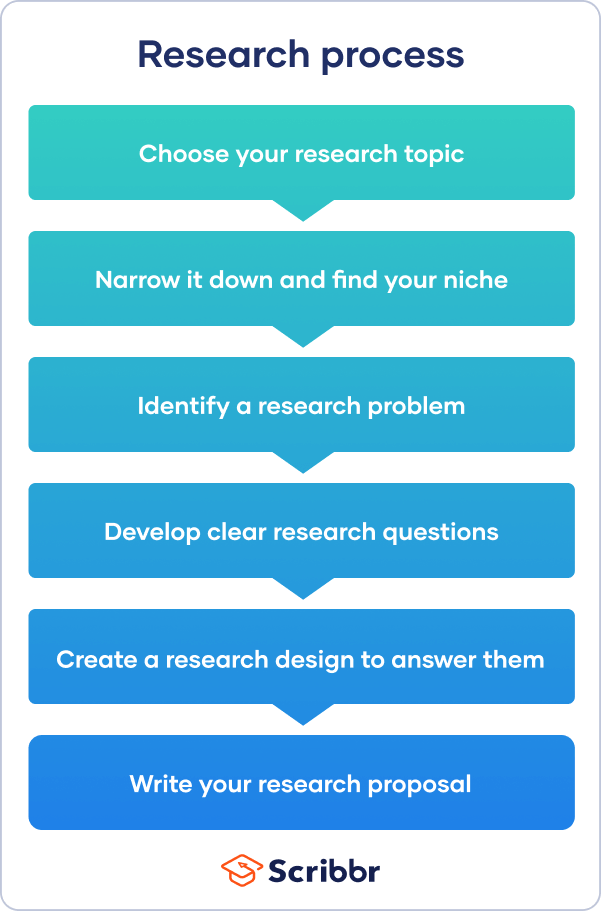

The Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Developing Research Questions

- Background Research

- Where to Search

- Narrow the Search

- Anatomy of a Detailed Record

- Scholarly vs. Popular Sources

- Primary, Secondary, & Tertiary Sources

- Evaluation Criteria

- Write, Review, and Reference

- Additional Help

Choosing a topic is research!

Once you have a general sense for a topic you are interested in, it is time to do some background research. Background research can help you develop your research question, narrow your focus, and guide the direction of your paper. You may even discover other aspects of the subject that you want to investigate.

Where to Conduct Background Research

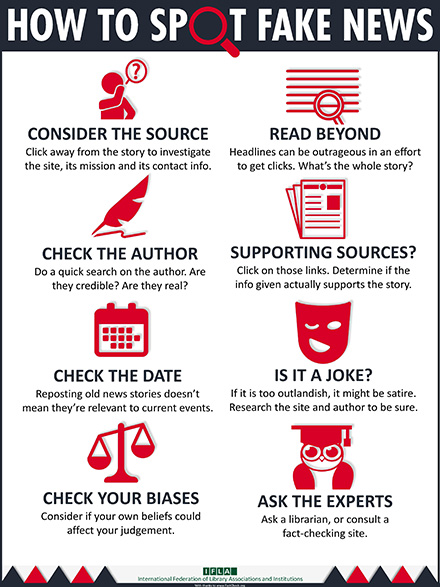

Google & Wikipedia

It is okay to get background information from a quick Google search. Ultimately, you will find more scholarly sources to use later in your paper, but Google and Wikipedia can provide you with a basic knowledge of the topic and provide you with additional keywords to use in your search.

Now offering more than 800 highly regarded reference titles from over 80 publishers, Credo Reference covers every major subject and also provides Topic Pages as a starting point for researchers.

Single Search & Research Starters

- << Previous: Developing Research Questions

- Next: Locate >>

- Last Updated: Jan 3, 2024 1:19 PM

- URL: https://goodwin.libguides.com/researchprocess

Background Research

What is background research, tyes of background information.

- General Sources

- Subject Specific Sources

Background research (or pre-research) is the research that you do before you start writing your paper or working on your project. Sometimes background research happens before you've even chosen a topic. The purpose of background research is to make the research that goes into your paper or project easier and more successful.

Some reasons to do background research include:

- Determining an appropriate scope for your research: Successful research starts with a topic or question that is appropriate to the scope of the assignment. A topic that is too broad means too much relevant information to review and distill. If your topic is too narrow, there won't be enough information to do meaningful research.

- Understanding how your research fits in with the broader conversation surrounding the topic: What are the major points of view or areas of interest in discussions of your research topic and how does your research fit in with these? Answering this question can help you define the parts of your topic that you need to explore.

- Establishing the value of your research : What is the impact of your research and why does it matter? How might your research clarify or change our understanding of the topic?

- Identifying experts and other important perspectives: Are there scholars whose work you need to understand for your research to be complete? Are there points of view that you need to include or address?