- Study protocol

- Open access

- Published: 11 September 2019

The effects of martial arts participation on mental and psychosocial health outcomes: a randomised controlled trial of a secondary school-based mental health promotion program

- Brian Moore ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8377-8579 1 ,

- Dean Dudley 2 &

- Stuart Woodcock 3

BMC Psychology volume 7 , Article number: 60 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

11 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mental health problems are a significant social issue that have multiple consequences, including broad social and economic impacts. However, many individuals do not seek assistance for mental health problems. Limited research suggests martial arts training may be an efficacious sports-based mental health intervention that potentially provides an inexpensive alternative to psychological therapy. Unfortunately, the small number of relevant studies and other methodological problems lead to uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of existing research. This study aims to examine the efficacy of a martial arts based therapeutic intervention to improve mental health outcomes.

Methods/design

The study is a 10-week secondary school-based intervention and will be evaluated using a randomised controlled trial. Data will be collected at baseline, post-intervention, and 12-week follow-up. Power calculations indicate a maximum sample size of n = 293 is required. The target age range of participants is 11–14 years, who will be recruited from government and catholic secondary schools in New South Wales, Australia. The intervention will be delivered in a face-to-face group format onsite at participating schools and consists of 10 × 50–60 min sessions, once per week for 10 weeks. Quantitative outcomes will be measured using standardised psychometric instruments.

The current study utilises a robust design and rigorous evaluation process to explore the intervention’s potential efficacy. As previous research examining the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes has not exhibited comparable scale or rigour, the findings of the study will provide valuable evidence regarding the efficacy of martial arts training to improve mental health outcomes.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Register ACTR N12618001405202 . Registered 21st August 2018.

Peer Review reports

Mental health problems are a significant social issue that have multiple consequences; ranging from personal distress, disability, and reduced labour force participation; to wider social and economic impacts. The annual global cost of mental health problems was estimated as $USD 2.5 trillion by the World Health Organisation [ 1 ]; and the annual cost of mental illness in Australia has been estimated as $AUD 60 billion [ 2 ]. These costs are projected to increase 240% by 2030 [ 1 ].

However, for a variety of reasons including stigmatisation of mental health and the cost and poor availability of mental health treatment, many individuals do not seek assistance for mental health problems [ 3 ]. Consequently, it is important to consider the application of alternative and complimentary therapies regarding mental health treatment. Martial arts training may be a suitable alternative, as it incorporates unique characteristics including an emphasis on respect, self-regulation and health promotion. Due to this, martial arts training could be viewed as a sports-based mental health intervention that potentially provides an inexpensive alternative to psychological therapy [ 4 ]. However, the efficacy of this approach has received little research attention [ 5 ].

Existing martial arts research has mostly focused on the physical aspects of martial arts, including physical health benefits and injuries resulting from martial arts practice [ 6 ], while few studies have examined whether martial arts training addressed mental health problems or promoted mental health and wellbeing. Several studies report that martial arts training had a positive effect reducing symptoms associated with anxiety and depression. For example: (a) training in tai-chi reduced anxiety and depression compared to a non-treatment condition [ 7 ], (b) karate students were less prone to depression compared to reported norms for male college students [ 8 ], and (c) a study examining a six-month taekwondo program reported significantly reduced anxiety [ 9 ]. Similarly, several studies report martial arts training promotes characteristics associated with wellbeing including: (a) a group of female participants reported higher self-concept compared to a comparison group after studying taekwondo for 8 weeks [ 10 ], and (b) a six-month taekwondo program found increased self-esteem following the intervention [ 9 ].

A recent meta-analysis examining the effects of martial arts training on mental health examined 14 studies and found that martial arts training had a positive effect on mental health outcomes (Moore, B., Dudley, D. & Woodcock, S. The effect of martial arts training on mental health outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis, Under review). The study found that martial arts training had a medium effect size regarding reducing internalising mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression; and a small effect size regarding increasing wellbeing.

However, despite generally positive findings the research base examining the psychological effects of the martial arts training exhibits significant methodological problems [ 11 , 12 ]. These include definitional and conceptual issues, a reliance on cross-sectional research designs, small sample sizes, self-selection effects, the use of self-report measures without third party corroboration, absence of follow-up measures, not accounting for demographic differences such as gender, and issues controlling for the role of the instructor. These issues may limit the generalisability of findings and suggest uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of previous research.

This study seeks to examine the relationship between martial arts training and mental health outcomes, while addressing the methodological limitations of previous studies. The intervention examined by the study is a bespoke programme based primarily on the martial art taekwondo and incorporating psycho-education developed for the intervention. Importantly, this study aims to examine the efficacy of a martial arts based therapeutic intervention to improve mental health outcomes.

Study design

This study is a 10-week secondary school-based intervention and will be evaluated using a randomised controlled trial. Ethics approval has been sought and obtained from an Australian University Human Research Ethics Committee, the New South Wales (NSW) Department of Education, and the Catholic Education Diocese of Parramatta. The study is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001405202). The study protocol was also reviewed externally by school psychologists employed by the NSW Department of Education.

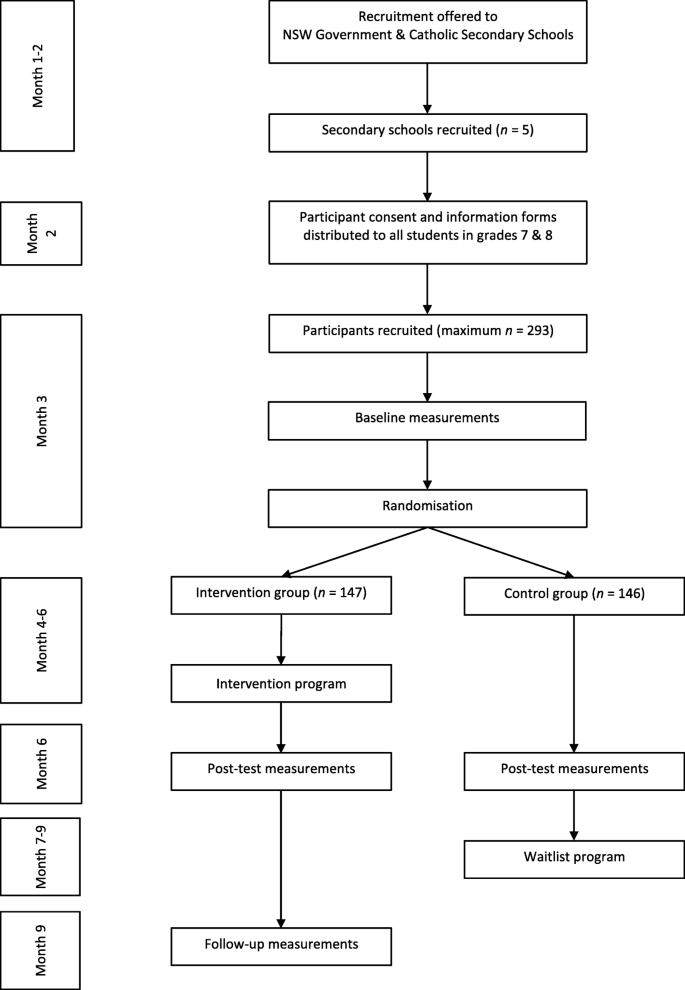

Researchers will conduct baseline assessments at participating schools after the initial recruitment processes. Following baseline assessments and randomisation, the intervention group will receive the intervention after which post-intervention assessment will be conducted. A 12-week post-intervention (follow-up) assessment will also be conducted. The control group will receive the same intervention program after the first post-intervention assessment and will not be measured at follow-up. The design, conduct and reporting of this study will adhere to the Consolidation Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for a randomised controlled trial [ 13 ]. Participants and caregivers will provide written informed consent.

Sample size calculation

Power calculations were conducted to determine the sample size required to detect changes in mental health related outcomes resulting from martial arts training. Statistical power calculations assumed baseline-post-test expected effect size gains of d = 0.3, and were based on 90% power with alpha levels set at p < 0.05. The minimum completion sample size was calculated as n = 234 (intervention group: n = 117, control group: n = 117). As participant drop-out rates of 20% are common in randomised controlled trials [ 14 ], the maximum proposed sample size was n = 293 (intervention group: n = 147, control group: n = 146).

Recruitment and study participants

To be eligible to participate in the study, schools must be government or catholic secondary schools in NSW, Australia. All eligible schools ( n = 140) will be sent an initial email with an invitation to participate in the study. Schools that respond to the initial email will be pooled and receive a follow up call in random order from the project researchers to discuss whether they would like to participate in the study. The first five schools that demonstrate interest will then be recruited into the study.

Inclusion criteria for participation in the study includes: (a) participants are currently enrolled in grades 7 or 8, and (b) participants are within an age range 11–14 years. Exclusion criteria: concurrent martial arts training will exclude participation in the study, however prior experience of martial arts training is not an exclusion criteria. All students at participating schools who meet these criteria will be invited to participate in the study. Participant and caregiver information and consent forms will be provided to students. Two follow-up letters will be sent subsequently at 2 week intervals. Students who respond to the invitation will be pooled and randomly allocated into the study, or not included in the study.

Randomisation into intervention and control group will occur after baseline assessments. A simple computer algorithm will be used to randomly allocate participants into intervention or control groups. This will be performed by a researcher not directly involved in the study. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the timeline for the study.

Flowchart of study

Intervention design

Intervention description.

The intervention will be delivered in a face to face group format onsite at participating schools. The intervention will be 10 × 50–60 min sessions, once per week for 10 weeks. Each intervention session will include:

Psycho-education – guided group based discussion. Topics include respect, goal-setting, self-concept and self-esteem, courage, resilience, bullying and peer pressure, self-care and caring for others, values, and, optimism and hope;

Warm up – including jogging, star jumps, push ups, and sit ups;

Stretching – including hamstring stretch, triceps stretch, figure four stretch, butterfly stretch, lunging hip flexor stretch, knee to chest stretch, and standing quad stretch; and,

Technical practice – including stances, blocks, punching, and kicking.

Additionally, intervention sessions intermittently include (alternated throughout the program):

Patterns practice – a pattern is a choreographed sequence of movements consisting of combinations of blocks, kicks, and punches performed as though defending against one or more imaginary opponents;

Sparring – based on tai-chi sticking hands exercise (which has been included as an alternative to traditional martial arts sparring); and

Meditation – based on breath focusing exercise.

In the final session the intervention will conclude with a formal martial arts grading where participants will be awarded a yellow belt subject to demonstration of martial arts techniques (stances, blocks, punching, and kicking) and the pattern learnt during the program. While it is desirable for participants to attend all 10 sessions to achieve intervention dose, it is unrealistic to assume all sessions will be attended. Research has suggested that determining an adequate intervention dose in health promotion programmes can be based on level of participation and whether participants did well [ 15 ]. In the current study intervention dose will be assumed if participants successfully complete the formal grading and are awarded a yellow belt. It is important to note that aggressive physical contact is not part of the intervention program. The intervention will be delivered by a (1) registered psychologist with minimum 6 years’ experience, and (2) 2nd Dan/level black-belt taekwondo instructor with minimum 5 years’ experience. Materials used during the intervention will include martial arts belts (white and yellow), and martial arts training equipment (for example strike paddles, strike shields).

Theoretical framework

The intervention development and implementation will be based on a traditional martial arts model, dichotomous health model, and social cognitive theory. Research examining the relationship between the martial arts and mental health has typically used a bipartite model [ 16 ] which distinguishes between traditional and modern martial arts. The intervention is based on a traditional martial arts perspective, which emphasizes the non-aggressive aspects of martial arts including psychological and philosophical development [ 17 ].

The absence of an explicit health model is a significant methodological limitation of previous research examining the mental health outcomes of martial arts training. The dominant models of mental health are based on the homeostatic assumption that normal health reflects the tendency towards a relatively stable equilibrium; and that the dysregulation of homeostatic processes causes ill-health [ 18 ]. These models can be defined dichotomously as having a: (1) pathological basis (deficit model) which refers to the presence or absence of disease based symptoms such as depression or anxiety; and (2) wellbeing basis (strengths model) which refers to the presence or absence of beneficial mental health characteristics such as resilience or self-efficacy. While considering both aspects of the mental health continuum, this study was particularly interested in the strengths model and examined the wellbeing characteristics of resilience and self-efficacy.

Social cognitive theory suggests that knowledge can be acquired through the observation of others in the context of social interactions, experiences, and media influences; and explains human behaviour in terms of continuous reciprocal interaction between personal cognitive, behavioural, and environmental influences [ 19 ]. The theory is useful for explaining the learning processes in the martial arts, which include: (a) modelling – where learning occurs through the observation of models; (b) outcome expectancies – to learn a modelled behaviour the potential outcome of that behaviour must be understood (for example, the anticipation of rewards or punishment); and (c) self-efficacy – the extent to which an individual believes that they can perform a behaviour required to produce a particular outcome [ 19 ].

The study’s theoretical framework incorporating a traditional martial arts model, dichotomous health model and social cognitive theory facilitates examination of the effects of martial arts training on mental health, ranging from mental health problems to factors associated with wellbeing such as resilience and self-efficacy. Further, the framework may determine the efficacy of martial arts training as an alternative mental health intervention that improves mental health outcomes.

Evaluation of the intervention program will involve a variety of standardised psychometric instruments to report on mental health related outcomes. Instruments include the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [ 20 ], Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) [ 21 ], and Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) [ 22 ]. All outcome time-points will be examined 1 week pre-intervention, 1 week post-intervention, and 12-week post-intervention (follow-up).

Behavioural and emotional difficulties

The primary outcome measured by the SDQ will be mean total difficulties. Additionally, the SDQ will measure the following secondary outcomes: emotional difficulties, conduct difficulties, hyperactivity difficulties, peer difficulties, and pro-social behaviour.

Total difficulties was selected as a primary outcome as it provides an overview of participants’ psychological problems. The SDQ scale is a commonly used psychometric screening tool recommended for use by the Australian Psychological Society [ 23 ] and has been normed for the Australian population.

The primary outcome measured by the CYRM will be mean total resilience. Additionally, the CYRM will measure the following secondary outcomes: individual capacities and resources, relationships with primary caregivers, and contextual factors.

Resilience was selected as a primary outcome as it is a current focus of research regarding psychological strengths, but has not been examined regarding the effect of martial arts training. The CYRM-28 was used in the study as it efficiently operationalises the theoretical aspects of resilience in a valid and reliable manner, but is shorter than comparable scales (for example the Resilience Scale for Children and Adolescents [ 24 ]).

- Self-efficacy

The primary outcome measured by the SEQ-C will be mean total self-efficacy. Additionally, the SEQ-C will measure the following secondary outcomes: academic self-efficacy, social self-efficacy, and emotional self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy was selected as a primary outcome as this operationalised a relevant component of social cognitive theory, which is important regarding the hypothesised learning processes in the intervention. The SEQ-C was used in the study as it operationalises self-efficacy for adolescents in an educationally relevant context.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes will be conducted using SPSS statistics version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, 2017) and alpha levels will be set at p < 0.05.

The collected psychometric test data will be consolidated into subscale variables using factor analysis and the internal consistency of each variable will be examined to determine reliability. Items to be included in the scale variables will be added and computed to create composite scores. Repeated measures univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) will primarily be used to analyse test data. Ordinal regression will be used to analyse test data based on psychometric measures using a 3-point Likert scale. Interpretation of effect sizes will reflect Cohen’s suggested small, medium, and large effect sizes, where partial eta squared sizes are equal to 0.10, 0.25, and 0.40 respectively [ 25 ].

Age, school grade level, sex, socio-economic status and cultural background will be included as covariates in the analysis.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes. The study will use a randomised controlled trial of secondary school aged participants.

Previous studies examining the impact of martial arts training on mental health and wellbeing have found positive results, which has also been confirmed by a systematic review and meta-analysis. Results have included martial arts training reducing symptoms associated with anxiety and depression; and promoting characteristics associated with wellbeing. However, the small number of relevant studies and noted methodological problems lead to uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of existing research.

The current study utilises a robust design with baseline, post-test and follow-up measures to examine the views of participants and includes a rigorous evaluation process using quantitative data to explore the program’s potential efficacy. This is a clear strength of this study and is important due to the study’s multi-site delivery. The current study has not used a qualitative approach which is a limitation of the research. Qualitative work is planned for future research to explore issues such as mechanism of impact.

The findings of this study will provide valuable evidence regarding the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes, and information for research groups looking for alternative or complementary psychological interventions. To our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes on a scale comparable to the current study while maintaining a similarly robust design and rigorous evaluation process. This study has the potential to change public health policy, and school-based policy and practice regarding management of mental health outcomes and enhance a range of health promoting behaviours in schools.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Australian dollar

United States dollar

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry Number

Analysis of variance

Consolidation standards of reporting trials

Child and youth resilience measure

Multivariate analysis of variance

New South Wales

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire

Self-efficacy questionnaire for children

Statistical packages for the social sciences

World Health Organisation. Out of the shadows: making mental health a global developmental priority. (2016). http://www.who.int/mental_health/advocacy/wb_background_paper.pdf Accessed 20 Jan 2018

Google Scholar

Australian Government National Mental Health Commission. Economics of Mental Health in Australia (2016). http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media-centre/news/economics-of-mental-health-in-australia.aspx Accessed 20 June 2018.

Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–25.

Article Google Scholar

Fuller J. Martial arts and psychological health. Brit J Med Psychol. 1988;61:317–28.

Macarie I, Roberts R. Martial arts and mental health. Contemp Psychothera. 2010;2:1), 1–4.

Burke D, Al-Adawi S, Lee Y, Audette J. Martial arts as sport and therapy and training in the martial arts. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 2007;47:96–102.

Li F, Fisher K, Harmer P, Irbe D, Tearse R, Weimer C. Tai chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. J Am Ger Soc. 2004;52:892–900.

McGowan R, Jordan C. Mood states and physical activity. Louis All Health Phys Ed Rec Dan J. 1988;15(12–13):32.

Trulson M. Martial arts training: a “novel” cure for juvenile delinquency. Hum Relat. 1986;39(12):1131–40.

Finkenberg M. Effect of participation in taekwondo on college women’s self-concept. Percept Motor Skills. 1990;71:891–4.

Tsang T, Kohn M, Chow C, Singh M. Health benefits of kung Fu: a systematic review. J Sport Sci. 2008;26(12):1249–67.

Vertonghen J, Theeboom M. The socio-psychological outcomes of martial arts practice among youth: a review. J Sport Sci Med. 2010;9:528–37.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz K, Montori V, Gotzsche P, Devereaux P, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:698–702.

Wood A, White I, Thompson S. Are missing outcome data adequately handled? A review of published randomized controlled trials in major medical journals. Clin Trials. 2004;1:368–76.

Legrand K, Bonsergent E, Latarche C, Empereur F, Collin J, Lecomte E, et al. Intervention dose estimation in health promotion programmes: a framework and a tool. Application to the diet and physical activity promotion PRALIMAP trial. BMC Med Res Meth. 2012;12:146.

Donohue J, Taylor K. The classification of the fighting arts. J Asian Mart Art. 1994;3(4):10–37.

Twemlow S, Biggs B, Nelson T, Venberg E, Fonagy P, Twemlow S. Effects of participation in a martial arts based antibullying program in elementary schools. Psychol Schools. 2008;45(10):1–14.

Antonovsky A. Unravelling the mystery of health. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987.

Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

Goodman, R. Strengths and difficulties questionnaire; 2005. http://www.sdqinfo.com .

Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L., Assessing Resilience across Cultures Using Mixed-Methods: Construction of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure-28. J Mixed-Meth Res. 2011; 5(2), 126–149.

Muris P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J Psych Behav Assess. 2001;23(3):145–9.

Australian Psychological Society. Clinical Assessment Resource. 2011 https://groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/Final_clinical_assessment_guide_January_2011.pdf Accessed 16 Aug 2018.

Prince-Embury S. Resilience scales for children and adolescents: a profile of personal strengths. Minneapolis: Pearson; 2007.

Richardson J. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Ed Res Rev. 2011;6(2):135–47.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Charles Sturt University, School of Teacher Education Faculty of Arts and Education, Panorama Avenue, Bathurst, NSW, 2795, Australia

Brian Moore

Macquarie University, Department of Educational Studies Faculty of Human Sciences, Balaclava Road, Macquarie, NSW, 2109, Australia

Dean Dudley

Griffith University, School of Education and Professional Studies Faculty of Arts, Education, and Law, Brisbane, QLD, 4122, Australia

Stuart Woodcock

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BM conceived the research aims, conducted the literature search, primarily wrote the manuscript and had primary responsibility for the final content. DD and SW reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stuart Woodcock .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval has been sought and obtained from an Australian University Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference No: 5201700901), the NSW Department of Education (Reference No: DOC18/257488), and Catholic Education Diocese of Parramatta (Reference No: 28032018).

Written consent to participate is required from participants and caregivers.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Moore, B., Dudley, D. & Woodcock, S. The effects of martial arts participation on mental and psychosocial health outcomes: a randomised controlled trial of a secondary school-based mental health promotion program. BMC Psychol 7 , 60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5

Download citation

Received : 20 September 2018

Accepted : 25 July 2019

Published : 11 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Martial arts

- Preventative medicine

- Alternative and complimentary therapies

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The effect of martial arts training on mental health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Teacher Education, Charles Sturt University, Panorama Avenue, BATHURST, NSW, 2795, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Macquarie University, Australia.

- 3 Griffith University, Australia.

- PMID: 33218541

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.06.017

Objective: Mental health issues are of increasing public concern, however are often untreated for a variety of reasons. While limited, the research examining the relationship between mental health and martial arts training is generally positive. This systematic review and meta-analysis explored whether martial arts training may be an efficacious sports-based mental health intervention.

Design: The meta-analysis used a random effects model and examined three mental health outcomes: wellbeing, internalising mental health, and aggression.

Data sources: During January to July 2018 the following electronic databases were searched: CENTRAL, EBSCO, Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, PUBMED, and ScienceDirect.

Eligibility criteria: Eligibility criteria included: (1) martial arts was examined as an intervention or activity resulting in a psychological outcome, (2) the study reported descriptive quantitative results measured using standardised scales that compared results between groups and (3) studies were published as full-length articles in peer reviewed scientific or medical journals.

Results: More than 500,000 citations were identified and screened to determine eligibility. Data was extracted from 14 eligible studies. Martial arts training had a significant but small positive effect on wellbeing (d = 0.346, 95% CI = 0.106 to 0.585, I 2 = 59.51%) and a medium effect on internalising mental health (d = 0.620, 95% CI = 0.006 to 1.23, I 2 = 84.84%). Martial arts training had a minimal non-significant positive effect in reducing aggression (d = 0.022, 95% CI = -0.191 to 0.236, I 2 = 58.12%).

Summary/conclusion: Whilst there is considerable variance across the studies included in the meta-analyses, there is support for martial arts training as an efficacious sports-based mental health intervention for improving wellbeing and reducing symptoms associated with internalising mental health.

Keywords: Aggression; Martial arts; Mental health; Mental illness; Wellbeing.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Declaration of competing interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Similar articles

- Well-being warriors: A randomized controlled trial examining the effects of martial arts training on secondary students' resilience. Moore B, Woodcock S, Dudley D. Moore B, et al. Br J Educ Psychol. 2021 Dec;91(4):1369-1394. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12422. Epub 2021 May 15. Br J Educ Psychol. 2021. PMID: 33990939 Clinical Trial.

- The effects of martial arts participation on mental and psychosocial health outcomes: a randomised controlled trial of a secondary school-based mental health promotion program. Moore B, Dudley D, Woodcock S. Moore B, et al. BMC Psychol. 2019 Sep 11;7(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5. BMC Psychol. 2019. PMID: 31511087 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

- Beyond the black stump: rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia. Osborne SR, Alston LV, Bolton KA, Whelan J, Reeve E, Wong Shee A, Browne J, Walker T, Versace VL, Allender S, Nichols M, Backholer K, Goodwin N, Lewis S, Dalton H, Prael G, Curtin M, Brooks R, Verdon S, Crockett J, Hodgins G, Walsh S, Lyle DM, Thompson SC, Browne LJ, Knight S, Pit SW, Jones M, Gillam MH, Leach MJ, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Muyambi K, Eshetie T, Tran K, May E, Lieschke G, Parker V, Smith A, Hayes C, Dunlop AJ, Rajappa H, White R, Oakley P, Holliday S. Osborne SR, et al. Med J Aust. 2020 Dec;213 Suppl 11:S3-S32.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50881. Med J Aust. 2020. PMID: 33314144

- Health benefits of hard martial arts in adults: a systematic review. Origua Rios S, Marks J, Estevan I, Barnett LM. Origua Rios S, et al. J Sports Sci. 2018 Jul;36(14):1614-1622. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1406297. Epub 2017 Nov 21. J Sports Sci. 2018. PMID: 29157151 Review.

- Martial arts and psychological health. Fuller JR. Fuller JR. Br J Med Psychol. 1988 Dec;61 ( Pt 4):317-28. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1988.tb02794.x. Br J Med Psychol. 1988. PMID: 3155357 Review.

- Hand-to-hand combat in the 21st century-INNOAGON warrior or modern gladiator?-a prospective study. Kruszewski A, Cherkashin I, Kruszewski M, Cherkashina E, Zhang X. Kruszewski A, et al. Front Sports Act Living. 2024 Apr 25;6:1383665. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1383665. eCollection 2024. Front Sports Act Living. 2024. PMID: 38725472 Free PMC article.

- Implementation of a Budo group therapy for psychiatric in- and outpatients: a feasibility study. Singh J, Jawhari K, Jaffé M, Imfeld L, Rabenschlag F, Moeller J, Nienaber A, Lang UE, Huber CG. Singh J, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2024 Feb 2;15:1338484. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1338484. eCollection 2024. Front Psychiatry. 2024. PMID: 38370554 Free PMC article.

- Exploring why young Australians participate in the sport of fencing: Future avenues for sports-based health promotion. Ganakas E, Peden AE. Ganakas E, et al. Health Promot J Austr. 2023 Feb;34(1):48-59. doi: 10.1002/hpja.650. Epub 2022 Aug 30. Health Promot J Austr. 2023. PMID: 36053861 Free PMC article.

- Arm Movement Analysis Technology of Wushu Competition Image Based on Deep Learning. Zhang X, Wu X, Song L. Zhang X, et al. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022 Aug 12;2022:9866754. doi: 10.1155/2022/9866754. eCollection 2022. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022. Retraction in: Comput Intell Neurosci. 2023 Aug 9;2023:9786309. doi: 10.1155/2023/9786309. PMID: 35990130 Free PMC article. Retracted.

- Parental Perceptions of Youths' Desirable Characteristics in Relation to Type of Leisure: A Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis of Martial-Art-Practicing Youths. Mickelsson TB. Mickelsson TB. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 8;19(9):5725. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095725. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35565118 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The effects of martial arts training on attentional networks in typical adults.

- School of Psychology, Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom

There is substantial evidence that training in Martial Arts is associated with improvements in cognitive function in children; but little has been studied in healthy adults. Here, we studied the impact of extensive training in Martial Arts on cognitive control in adults. To do so, we used the Attention Network Test (ANT) to test two different groups of participants: with at least 2 years of Martial Arts experience, and with no experience with the sport. Participants were screened from a wider sample of over 500 participants who volunteered to participate. 48 participants were selected: 21 in the Martial Arts group (mean age = 19.68) and 27 in the Non-Martial Arts group (mean age = 19.63). The two groups were matched on a number of demographic variables that included Age and BMI, following the results of a previous pilot study where these factors were found to significantly impact the ANT measures. An effect of Martial Arts experience was found on the Alert network, but not the Orienting or Executive ones. More specifically, Martial Artists showed improved performance when alert had to be sustained endogenously, performing more like the control group when an exogenous cue was provided. This result was further confirmed by a negative correlation between number of years of Martial Arts experience and the costs due to the lack of an exogenous cue suggesting that the longer a person takes part in the sport, the better their endogenous alert is. Results are interpreted in the context of the impact of training a particular attentional state in specific neurocognitive pathways.

Introduction

Being able to attentionally focus on a task, and therefore avoid distraction, is fundamental to achieving our goals. Despite its central role in human adaptation to life, it is one of the most vulnerable cognitive functions. This is evidenced by the level of research showing the number of variables that deficits in attention can be attributed to, such as genetics ( Durston et al., 2006 ), mental illness ( Clark et al., 2002 ), and traumatic brain injury ( Shah et al., 2017 ), among others. Age has perhaps the biggest influence on attentional control with a large amount of research discussing the decline in this function in older adults ( Milham et al., 2002 ; Kray et al., 2004 ; Jennings et al., 2007 ; Deary et al., 2009 ; Carriere et al., 2010 ; Dorbath et al., 2011 ). Deterioration of attentional control is variable but generally progressive, establishing it as the best predictor of cognitive dysfunction in older people. In neural terms, attentional control is achieved by the coordinated activation of a number of attentional networks with various specialities depending on the type of control required, although not all of these networks are affected by age in the same manner ( Jennings et al., 2007 ).

Compared to how easily attentional control seemingly declines, little is known about whether we can enhance this function, and if so, how. In this paper, we evaluate the impact of Martial Arts experience on three different attentional networks: Alert, Orienting, and Executive. These networks have been neuroanatomically validated and reported as being largely independent of one another ( Fan et al., 2002 ). The results provided in this paper are important in aiding understanding of the impact of experience on these networks, whilst also highlighting potential intervention strategies.

Attentional Control in Martial Arts

Tang and Posner (2009) suggested that there are two different ways to improve attentional control: Attention Training (AT, also called Network Training; Voelker et al., 2017 ) and Attention State Training (AST). AT comes from Western cultures and is mostly based on specific task practice; over the past decade it has become popularized and marketed as ‘brain training’ games ( Boot et al., 2008 ; Bavelier and Davidson, 2013 ). This means that much research into AT focuses on training participants on a certain task to improve a specific cognitive skill, yet these improvements often are not transferable to tasks measuring other skills ( Rueda et al., 2005 ). For example, training at an attentional task will only improve the skills required for attentional tasks similar in nature ( Thorell et al., 2009 ). Despite this, improvements are often found in this type of AT research. Participants given training in playing an action video game were shown to present an increase in visual attention, in comparison to those given training in playing Tetris ( Green and Bavelier, 2003 ). This is possibly due to the need to stay vigilant whilst also scanning the screen for targets or enemies during this type of game. In addition to the improvement not being transferable, this improvement seems to be short-term, rather than the long-term improvement researchers are striving for Tang and Posner (2009) .

On the other hand, AST is based on Eastern cultures and aims to improve attention through a change in state of mind and body, also claiming to provide a better transference to other tasks not specifically trained by the activity ( Tang and Posner, 2009 ). AST can be found in activities such as yoga, mindfulness, meditation, and Martial Arts. Gothe et al. (2013) used healthy, adult participants to investigate the effects of yoga on cognitive control. Participants were asked to visit the laboratory on three occasions to complete some computerized behavioral tasks after a different activity on each day: (1) a 20-min yoga session; (2) a 20-min exercise routine on a treadmill; (3) no activity in order to collect baseline data. The order of the three activities was randomized. A flanker task and an n-back task were used to provide measures of attentional control, and results indicated that the yoga session provided an improvement across both of these tasks. Interestingly, these benefits were not seen after the aerobic exercise condition, perhaps suggesting that the exercise element of yoga is not the sole force behind the effects. Similarly, Moore and Malinowski (2009) found a correlation between mindfulness experience and improved performance in attention and response inhibition tasks. However, unlike the Gothe et al. (2013) experiment, this was a cross-sectional design using the amount of mindfulness experience as a variable rather than results after a single session.

Martial Arts includes similar aspects to mindfulness and yoga, and could potentially produce similar improvements in attentional control, although much of the research with Martial Arts has been conducted with school aged children ( Diamond and Lee, 2011 ). For example, during an academic year, an average of three sessions of Taekwondo per week showed improvements in working memory and attention, as well as parentally-reported benefits in concentration and behavioral inhibition ( Lakes et al., 2013 ). Additionally, a recent large-scale review of 84 studies conducted by Diamond and Ling (2016) found that Martial Arts, mindfulness, and Montessori Teaching produced the widest range of benefits in executive control tasks in children when compared with other interventions such as team sports, aerobic exercises, board games, or adaptations to the school curriculum. This review also raised an important point, noting that the greatest benefits were found in the children with the lowest starting scores in cognitive tests, and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This observation indicates that the greatest benefits from this type of intervention should be observed in those who display poor cognitive control and that neurotypical populations composed of developed young adults may already be at a ceiling in their attentional performance. Indeed, reports of improved cognitive abilities in younger adults are rare. Most of the benefits have been found in the sensorymotor system, involving corticospinal excitability due to long term training in Karate ( Moscatelli et al., 2016b ), or in the excitability of the motor cortex in Taekwondo athletes ( Moscatelli et al., 2016c ). Interestingly, some of these pathways coexist with more cognitive networks, such as attentional networks (as reviewed further on), raising the possibility of successfully finding changes in cognition with neurotypical adults despite the lack of previous reports.

Conversely, one would expect some improvements in older adults due to the evidence suggesting an age-related decline in cognitive control. Kray et al. (2004) suggested that if cognitive control was plotted on a graph along the lifespan, then it would take the shape of an inverted ‘U,’ with performance improving as a person ages, remaining relatively stable during early adulthood, and then declining again as a person grows older. Studies using older populations to investigate the effects of Martial Arts on attentional control remain elusive, possibly due to the physical demands the sport requires, however that is not to say that this type of research is impossible. Jansen and Dahmen-Zimmer (2012) recruited participants aged 67–93 to compare the effects of Karate training in comparison to general physical exercise training, and cognitive training. This training took place over 20 sessions over 3–6 months, yet despite an increase in well-being reported by those in the Karate training group, there were no significant effects on cognitive speed or working memory across any of the groups.

However, it is important to note that outside laboratories, Martial Artists usually measure their differences in training in terms of years, rather than weeks or months, so it is conceivable that short interventions would not achieve the state of mind characteristic of the discipline. Witte et al. (2015) built on previous research and studied three different groups of participants, with an age range of 63–83. They compared a group training in Karate, with another training in fitness and with a passive control group that did not complete any sports intervention. The results showed that the Karate group displayed small improvements in each of the four tasks performed. In a test of divided attention, for example, this improvement was not quite significant ( p = 0.063) after 5 months but, after another 5 months of extra training, the level of improvement further increased, reaching more reliable effects ( p = 0.002). These results clearly suggest that, at least in adults, potential benefits may need a longer time of training to emerge than those normally used in pre–post intervention studies.

To sum up, much of the research into the effects of Martial Arts on attentional and cognitive control has used either school-aged children or older adults. There appears to be a lack research focusing on healthy, neurotypical, adult participants. This population seems to need longer periods of training to show any improvement in other transference tasks, and this is the gap that we aim to fill with our current research.

The Attention Network Test

A limitation of comparing much of the previous research is the wide range of measures used to assess attentional control, potentially leading to inconsistency across studies. One way to reduce this problem is to avoid using general measures (such as academic results or IQ) that result in difficulties isolating the core mechanisms behind the benefits. The problem could also be countered by using tasks which have been validated as measuring specific functions that have been localized to neuroanatomical locations.

Petersen and Posner (2012) discussed recent literature in attentional control and confirmed the existence of three core networks of attention in the human brain: Alert, Orienting, and Executive ( Posner and Petersen, 1990 ). They suggested that these networks are independent of each other, each having distinct neuroanatomical structures, and responsible for a different aspect of attention. The alert index is related to optimal vigilance, Orienting has associations with the spatial location of targets, and executive has been linked with conflict resolution. Measures of these indexes can be collected using the Attention Network Test (ANT; Fan et al., 2002 ), which utilizes a modified flanker task with four cues types to produce various trial types. The Alert index gives a measure of how well a person is able to respond to targets appearing at unpredictable intervals (uncued) compared to a predictable one (time cued). The Orienting index assesses how well-participants can orient to a target that appears in an unpredictable location (uncued) compared to a certain one (spatially cued). Finally, the executive index evaluates how well-participants can resolve response conflict in a flanker task, where distractors evoke the same response as the target (congruent) or the opposite one (incongruent). Behaviorally, all these three indexes are interpreted as costs, where large differences in RTs or accuracy reflect poor control ( Fan et al., 2002 ; Jennings et al., 2007 ; Petersen and Posner, 2012 ).

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been used to assess the neural activity related to the three attentional networks measured by the ANT. It has been suggested that these three networks are independent of each other, and while there is some overlap, the functional response for each network has a distinct anatomical location ( Fan et al., 2005 ). The Alert index seems to involve norepinephrine circuits connecting the locus coruleus with the right frontal and parietal cortices. The Orienting index is mostly driven by acetylcholine areas engaging the superior parietal cortex, temporoparietal junction frontal eye fields and superior colliculus. Finally, the Executive network activates dopamine based areas including the anterior cingulate, lateral and ventral prefrontal cortices, and the basal ganglia. When a particular sensory event is presented, it is believed that the coordinated activation of these three networks makes it possible to react to them with fast and accurate responses.

Training in Martial Arts is a wide-reaching experience involving not only a great level of motor training but also a mental state of concentration and reactivity to targets with a strong social context. Because of this, it is difficult to confidently predict where the improvements, if any, should be observed. There are, however, different aspects of the training that could impact directly these indexes. For example, during sparring, Martial Artists need to continuously scan the body of the opponent for an opening where they can score. As this may happen at any particular time, training in sparring may transfer to other tests involving target detection at random intervals, as measured by the Alert index. In addition to scoring, the Martial Artist needs to avoid and block any incoming hit from the opponent. This requires not only good timing (also linked to the alert system) but enhanced spatial orienting to the exact location where the hit comes from. Following the example of sparring, Martial Artists also throw feigned punches and kicks to distract the opponent’s attention in order to score with an unexpected move. Not reacting to these in order to better respond to the real ones should require response conflict control of the type measured by the Executive index. Of course, it is not just sparring that is involved in Martial Arts training. Equally, these aspects are not exclusive of Martial Arts and can be shared with many other activities such as tennis, fencing, dancing, etc. But they at least represent a context of repetitive training on specific skills that are comparable to those used in AT studies, such as brain training. With the added element of concentration, meditation, and discipline (as is typical in AST research), it provides a promising strategy for training in attentional control.

In this study, we compared two groups of participants screened from a wider sample of 500 young adults. One group was composed of Martial Artists with at least 2 years of experience while the others had no previous experience with Martial Arts. Because of the requirements of extensive training, assignation to the groups could not be random, so special care was taken during the matching process to eliminate the most relevant potential confounds. As there is no previous literature of the influence of different demographics on ANT, we previously ran a pilot where these confounds were detected.

The aim of this study was to assess the performance of Martial Artists and Non-Martial Artists on the three indexes of attention, as measured by the ANT. We hypothesized that smaller indexes, reflecting improved performance, would be observed in the Martial Arts group in comparison to Non-Martial Artists.

Materials and Methods

Participants and screening procedure.

An unpublished pilot study using an unbiased random sample of 41 undergraduate students of Psychology at Bangor University was used to test the ANT in the general population according to different demographic and lifestyle factors. This pilot showed that Age and Body Mass Index (BMI) both had significant effects on ANT performance, and so based on this we decided to match the Martial Arts and Non-Martial Arts groups mainly on these two variables among others.

Using G ∗ Power 3.0.10, an a priori calculation of optimal sample size was calculated based on parameters taken from the pilot study. When using stringent criteria such as a correlation of 0.6 between measures, a desired power of 0.95, and an alpha level set to 0.05, it was estimated that a minimum sample size of 30 participants would be needed to reach an effect size of 0.25 from the required 2x2x2 ANOVA (see section “Design and Procedure”). This would result in 15 participants in each of the two participant groups.

A screening questionnaire was introduced and distributed online to over 500 new people including Bangor University undergraduates and non-students from the local community. These responses then made up a participant pool which was used to create two experimental groups matched on the aforementioned variables: one group with no Martial Arts experience ( n = 27, five males), and the second with those who had undertaken Martial Arts practice during the last 2 years ( n = 21, six males). The Martial Arts group was made up of participants with experience in Karate (5), Taekwondo (3), Kickboxing (3), Jujitsu (3), Tai Chi (2), Judo (2), Thai Boxing (2), and Kung Fu (1). This sample exceeded the minimum sample size estimated by the power calculation. The participants from these groups were invited to participate in the ANT phase. The Non-Martial Arts group reported taking part in activities such as going to the gym, playing team sports, meditating, praying, and playing musical instruments.

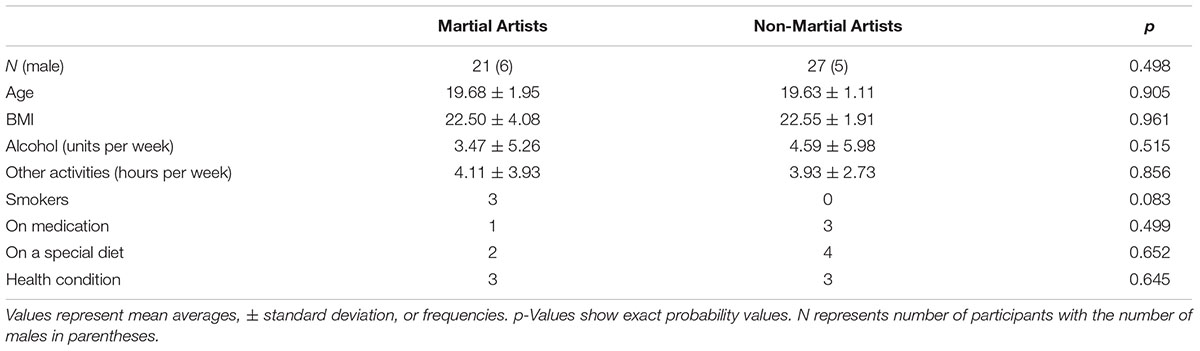

Students from Bangor University were reimbursed for their time with course credits, and those from the community were given a monetary token of £6. All participants were neurotypical, had normal or corrected to normal vision, and normal hearing. This study gained approval from the Bangor University Ethics and Governance Committee (Ethics Approval #2015-15553) and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. As a condition of this approval, all participants provided fully informed consent prior to taking part. Information regarding the demographics of the selected participants can be found in Table 1 .

TABLE 1. Descriptive data for key participant demographics.

Stimuli and Apparatus

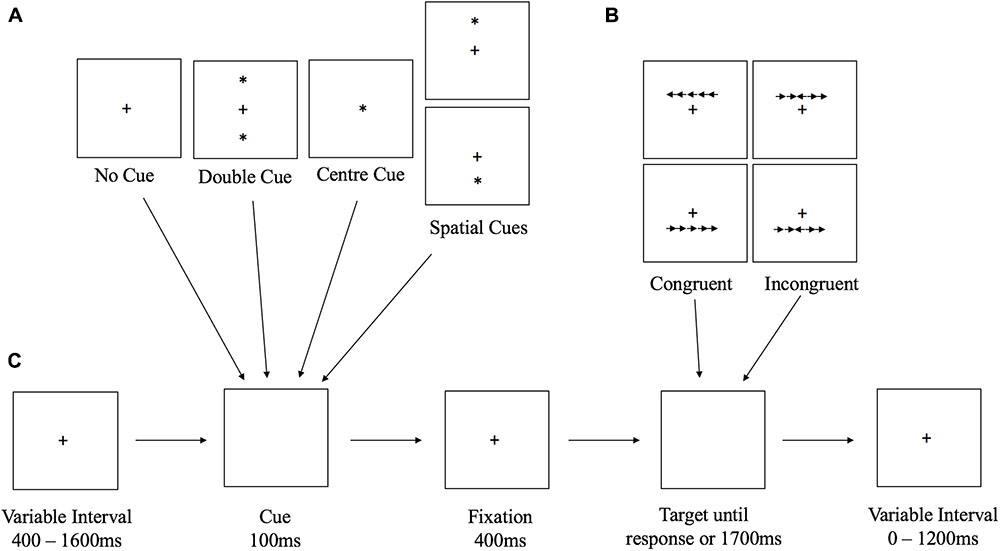

This experiment was presented using EPrime 2.0 [Psychology Software Tools (PST)]. Responses were recorded using a QWERTY keyboard, with the ‘C’ and ‘M’ keys as the response keys. Target stimuli consisted of a row of five black arrows on a white background, facing to either the left or right side of the screen; each arrow subtended 0.53° of a visual angle, with a gap of 0.09°. The complete series of arrows subtended 2.73°. Participants were required to press the left key (C) or the right key (M) in response to the direction of the central arrow. This could be in either a congruent position (facing the same way) to the other arrows, or in an incongruent one (facing the opposite way). These were displayed either 0.71° of a visual angle above or below a fixation cross in the center of the screen (see Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1. Diagram showing (A) all possible cue types, (B) the target types, and (C) trial timings and procedure.

The target stimulus was preceded by one of four cue configurations (Figure 1 ): no cue, center cue, double cue, and spatial cue. Each cue was made up of a black asterisk the same size as the fixation cross (0.44° of a visual angle tall; 0.44° wide) and appeared for 100 ms before the target (Figure 1 ). During the no cue condition, an asterisk did not appear, instead, the fixation cross remained on screen. For the center cue conditions, the asterisk simply replaced the fixation cross. Double cue conditions consisted of an asterisk appearing both above and below the fixation cross. Finally, during spatial cue conditions, the asterisk appeared either above or below the fixation cross, and always provided a true indication of the location in which the target would appear.

Each trial began with a fixation cross presented during variable intervals (400–1600 ms) and ended with another fixation cross appearing just after the response to the target also with a variable duration to make the total interval time 1600 ms per trial. After the first interval, the cue appeared on screen for 100 ms, followed by another fixation cross for a fixed duration of 400 ms. The target then appeared and remained on screen until the participant responded, or until 1700 ms had passed. Responses exceeding this limit were recorded as errors.

Design and Procedure

The study took a 2 (participant group) × 2 (trial type) × 2 design (target congruency – executive) design. For the Alert index this would look like 2 (Martial Arts vs. Non-Martial Arts) × 2 (no cue vs. double cue) × 2 (congruent target vs. incongruent target). Whereas for Orienting it would take the form of 2 (Martial Arts vs. Non-Martial Arts) × 2 (center cue vs. spatial cues) × 2 (congruent target vs. incongruent target). The Alert and Orienting networks come from cue manipulations, and are independent due to them using different trial types in their calculations, however the Executive network comes from a target manipulation and is therefore not independent of the Alert and Orienting networks. As a result, we will analyze this as an interaction.

Upon arrival in the laboratory, participants were provided with information about the experiment, given the opportunity to ask questions, and provided with a consent form. After receiving fully informed consent, participants were presented with the demographics questionnaire, before being asked to complete the ANT by responding to the direction of a central arrow as described earlier.

A practice block of 24 trials was presented to participants to ensure all instructions were understood; no feedback was provided. Once completed, participants moved onto the experimental block of 128 trials, before having a break of a length determined by the participant, which was then followed by another 128 trials. Again, no feedback was provided.

Data Analysis

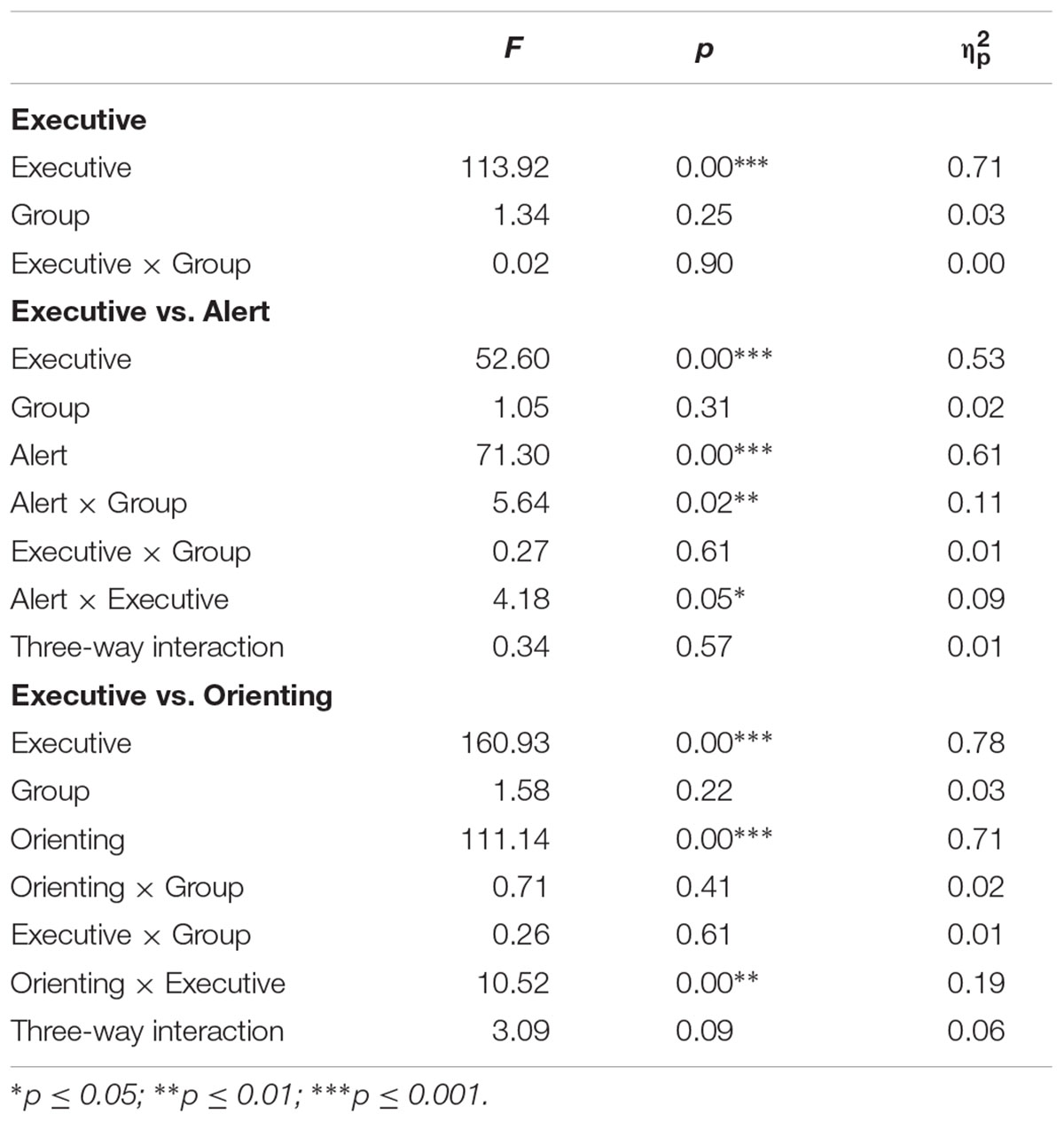

All data was pre-processed within EPrime 2.0 (PST). Incorrect trials were removed from the analysis, as were those with a response time greater than 1000 ms. Once the filtering in EPrime was complete, the data was moved over to SPSS v.22 for statistical analysis, and split into the two participant groups based on the criteria mentioned above for Martial Arts experience. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean averages, ± standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequencies for categorical variables (see Table 1 ). Differences between the groups were estimated using independent samples t -tests, whilst differences in frequencies were assessed using chi square. The three indexes, Alert, Orienting, and Executive, were then created using the calculations described by Fan et al. (2002) . These are expressed as mean cost indexes. Mean RT averages per participant, per condition were analyzed through three different general linear models (see Table 2 ). Effect sizes for these effects are estimated through partial eta squared. When Martial Arts group differences were found, correlations were conducted with years of experience using the Pearson’s coefficient.

TABLE 2. F -values, probability values ( p ) and effect sizes ( η p 2 ), for all conducted general linear models.

Data were separately analyzed for each of the attentional indexes.

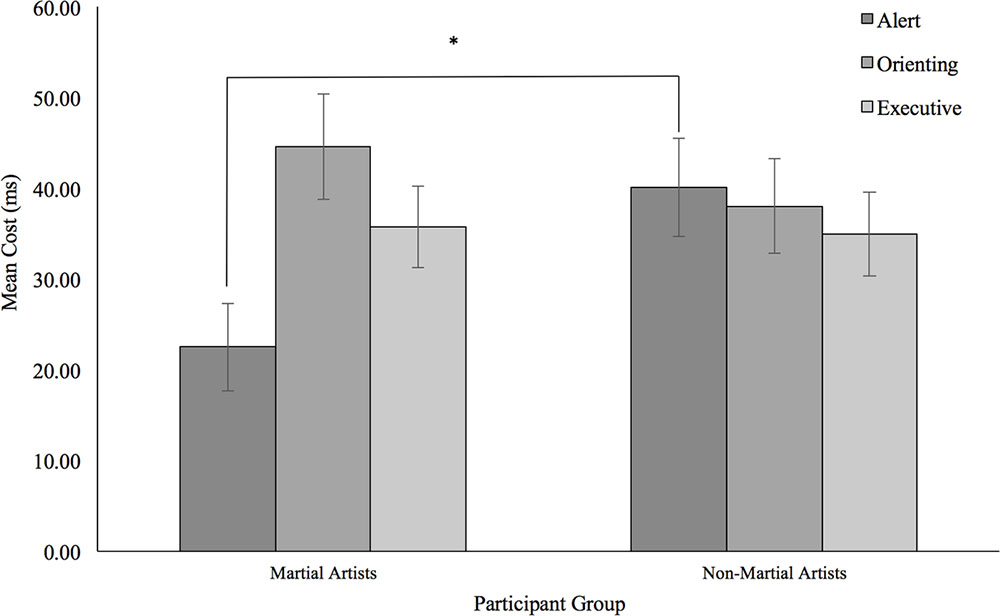

When the Executive index was analyzed in isolation, we found an overall increase of 36 ms for incongruent trials compared to congruent ones [ F (1,46) = 1013.92; p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.1]. This effect was almost identical for the Martial Arts group (36 ms) compared to the Non-Martial Arts one (35 ms, F < 1) (see Figure 2 ).

FIGURE 2. Graph depicting the mean cost for each of the three attentional network, for both participant groups. Error bars represent Standard Error. ∗ p < 0.05.

Executive vs. Alert

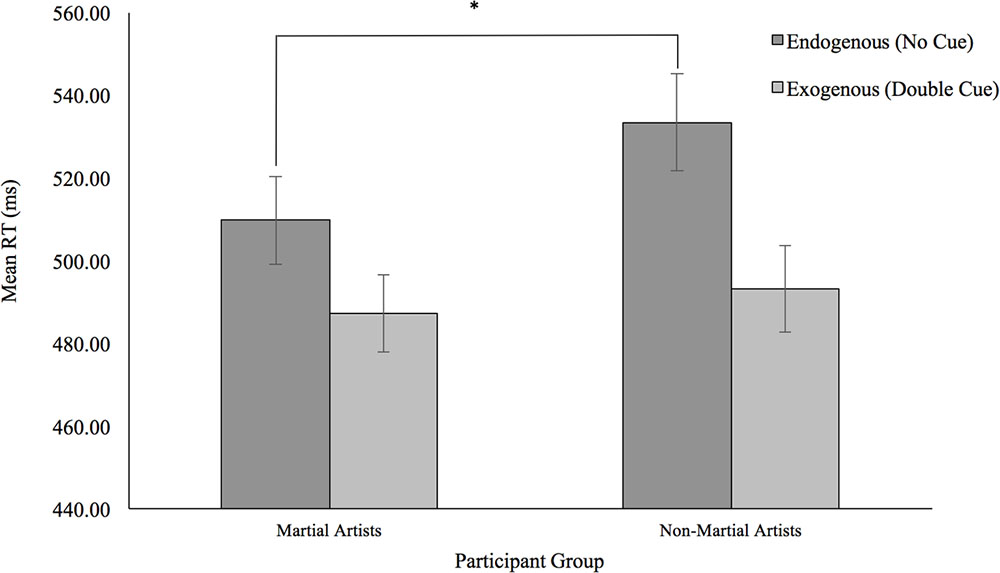

Mean RTs per participant per condition were submitted to a mixed factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Martial/Non-Martial Arts variable as a grouping factor and the Type of Cue (Double Cue, no Cue) and Congruency (Congruent, Incongruent) as repeated measures. Results indicated no overall differences in RTs across the groups ( p = 0.31). Responses to targets preceded by the double cue were 32 ms faster than those without a cue as would be expected as a measure of Alert. More importantly, this benefit from the double cue was 18 ms smaller in the Martial Arts group compared to the Non-Martial arts group [ F (1,46) = 5.64; p = 0.022; η p 2 = 0.642] (see Figure 2 ). Although group differences did not reach significance in any of the conditions, Non-Martial Artists were found to be particularly slower than the Martial Artists when no cue was presented (24 ms), while both groups seemed more similar with the double cue (6 ms) (see Figure 3 ). Congruent trials were overall 32 ms faster than incongruent ones [ F (1,46) = 52.59; p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.1], but this effect did not change with the group ( F < 1). Interestingly, the executive congruency effects were more evident in the double cue trials (38 ms) than with no cue (27 ms) [ F (1,46) = 4.18; p = 0.047; η p 2 = 0.516]; but this was found in general for all participants and did not change across the groups ( p = 0.57).

FIGURE 3. Graph depicting the mean RT for the trial types that make up the Alert index, no cue trials and double cue trials. Mean RTs are displayed for both participant groups. Error bars represent Standard Error. ∗ p < 0.05.

Executive vs. Orienting

Mean RTs per participant per condition were also submitted to a mixed factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Martial/Non-Martial Arts variable as a grouping factor and the Type of Cue (Spatial, Center Cue) and Congruency (Congruent, Incongruent) as repeated measures. As before, no overall differences were found between the Martial Arts and the Non-Martial Arts groups ( p = 0.22) (see Figure 2 ). Congruent trials were found to be 38 ms faster than the incongruent ones [ F (1,46) = 160.93; p < 0.0001; η p 2 = 1]. Also, spatial cues produced responses that were 41 ms faster than the single central cue [ F (1,46) = 111.14; p < 0.0001; η p 2 = 1]. Interestingly, the congruency effects changed depending on the type of spatial cueing [ F (1,46) = 10.52; p = 0.002; η p 2 = 0.89], with a flanker congruency effect of 47 ms in the center cue condition congruent trials that was reduced to 29 ms with the spatial cue.

Attentional Networks Correlations

We analyzed whether there were any interactions across attentional networks by calculating the correlations across the three indexes. Results demonstrated a marginally significant correlation between the Alert and Executive indexes only ( r = -0.262; p = 0.072).

A correlation was also done on the three indexes of attention and the number of years of Martial Arts practice. No significant correlation between Orienting and number of years was found, r = 0.121, n = 46, p = 0.421, nor between Executive and number of years, r = 0.039, n = 46, p = 0.798. However, a correlation nearing significance was found between the Alert index and the number of years of practice, r = -0.274, n = 46, p = 0.065.

Finally, a series of analyses were run on the accuracy of responses to each trial type. For each participant, a percentage (%) accuracy score was calculated for each type of trial (cue type and congruency type), and these were then compared between groups. There were no significant differences between the two participant groups for any trial type for the ANT, suggesting that all trials were equally as difficult. Less than 16% of overall responses were recorded as errors.

In this paper, we provide evidence that training in Martial Arts is associated with improvements in the Alert attentional network. This appears to be a specific benefit that boosts endogenous preparation for uncertain targets, as suggested by the increased benefits in the uncued conditions in comparison to a lack of improvement in the cued conditions. This means that when an upcoming target had no cue, the Martial Artists performed at a higher level, however when the target had a reliable cue, these group differences disappeared. Importantly, the Alert benefits observed in the MA group was further supported by the negative correlation found between the Alert index and the number of years of training.

The use of ANT allows us to speculate on the nature of these benefits, as explained in the introduction. Previous research with this task using neuroimaging techniques found that the Alert index is linked to the activation of a norepinephrine based network connecting the locus coeruleus with the right frontal and parietal cortices, as well as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2005 ; Raz and Buhle, 2006 ; Petersen and Posner, 2012 ). The locus coeruleus is a nucleus in the brainstem in charge of producing norepinephrine, which has an excitatory effect on the rest of the brain, resulting in an increased level of arousal. As a result of this activation, different parts of the brain involved in perceptual and motor processing get primed to enable faster responses to stimuli ( Moscatelli et al., 2016a , b ; Monda et al., 2017 ).

It is not yet clear which aspect of Martial Arts training may be driving the effect on the alert index, or indeed where the effect is coming from. Further work using neuroimaging techniques may allow us to gain an insight into these details. For example, Fan and Posner (2004) suggested the use of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to look at the attentional networks’ functional connectivity; by understanding how these circuits work in a typical group of participants, we could then begin to investigate whether Martial Arts experience has any effect, which would then be able to show us where the effect on alert is observed at a neural level. Of course, it is conceivable that Martial Artists who trained for years on fast reactions to stimuli may have modeled their brains to lower the activation threshold of areas involved in perceptual processing and motor control ( Moscatelli et al., 2016c ). However, we would expect this influence to appear across all conditions, for both predictable and unpredictable targets, simply inducing faster reaction times, rather than any exclusive benefits. This idea is not supported by the results which suggested no significant differences in overall RTs in the Martial Arts group in comparison to the Non-Martial Arts controls.

An interesting aspect of our results is that the strongest benefits seem to appear more specifically in the unpredictable condition. Somehow, our Martial Artists seem to be more capable of inducing these increases in arousal to improve sensorimotor processing endogenously without the aid of external cues. Indeed, there is evidence that endogenous time allocation of attention to the particular moment when a target appears improves identification of masked targets that otherwise would have been unconsciously processed ( Naccache et al., 2002 ). More importantly, it has also been found that identifications were better for targets closer to the expected time frame than for more distant ones in time. When this is considered in relation to our findings, it raises the possibility that Martial Artists may endogenously hold the level of vigilance for longer periods of time reaching the unpredictable target in a more efficient way than controls.

This interpretation is supported by recent findings of increased excitability of the corticospinal motor system in Karate athletes ( Moscatelli et al., 2016a , b ; Monda et al., 2017 ). In this study, the authors found that this greater excitability from the Karate group was evidenced in faster reaction times to targets appearing in variable intervals (as is standard in the Reaction Time [RTI] test from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery [CANTAB ® ]). Related findings from this team have also found excitability of the motor cortex in Taekwondo athletes ( Moscatelli et al., 2016c ), suggesting that this effect may be found in other types of Martial Arts. In the current study, when the target appeared in a predictable interval, no group differences were found. Our Martial Arts group were faster than the Non-Martial Arts group only with unpredictable targets, thereby supporting Moscatelli colleagues findings. Interestingly this RTI task was also described as a vigilance task. Our results can be seen as a step forward, further suggesting that the excitability of this corticospinal motor system may be linked to the improved activity in the Alert network due to Martial Arts practice.

Although previous research seems to assume that the three attentional networks studied here largely independent, there is some evidence of influences across them. For example, spatial orienting seems to have a fundamental role in the activation of competing responses during a flanker task in what it would seem like a modulation of the Orienting network over the Executive one ( Vivas and Fuentes, 2001 ). Also, when testing neglect patients, increased alert can be used to improve target detection in the hemifield contralateral to the site of the lesion ( Robertson et al., 1995 ), demonstrating an influence of the Alert network over the Orienting one. In our data, we did not find any correlation between Alert and Orienting, neither Orienting with Executive. However, we did find a strong correlation between Alert and Executive, since greater congruency effects were found in the predictable condition. Further support may come from studies finding that increases in norepinephrine improve executive response selection ( Chamberlain et al., 2006 ). This also fits well with results described earlier in which response congruency effects were only found at the spatially cued location ( Vivas and Fuentes, 2001 ). Basically, the executive resolution of conflict elicit by incongruent flankers requires first the selection of the target, both spatially and temporally. Although this is an interesting aspect of the data, it nevertheless did not change with the group, not being affected by training in Martial Arts.

The benefits associated with MA training in our study seem to be exclusive to the Alert system, mostly with regards to endogenous alert. Importantly, this improvement increases with years of practice extending up to 18 years. These results are important because it highlights the potential difficulties of getting significant results from studies of using randomized groups with a training intervention of only a few months. Nevertheless, one of the biggest disadvantages of using cross-sectional samples is the lack of control of group variables. In order to improve the control over the current study, participants were carefully matched on various variables. To find two homogeneous participant groups, demographic information for over 500 people was collected and then filtered based on age, BMI, lifestyle, and health factors such as smoking status, and level of education. To avoid ending up with an active participant group and a passive participant group, we ensured that control participants were only recruited if they reported taking part in several hours of activity per week. The activities reported included gym time, football, and basketball among others, suggesting that the control participants were just as active as the Martial Artists. We believe that this is an important variable to use with regards to matching the groups to ensure a similar level of fitness due to previous research suggesting a link between fitness and cognitive control. Our estimation, however, has been based on a non-validated self-report measure so should be considered with caution. In any case, the descriptive data showed no significant differences in terms of hours of participating in other activities per week between the two groups.

A further consideration comes from the heterogeneity of participants in the Martial Arts group, specifically in relation to the styles of Martial Arts. In the current paper, different styles of Martial Arts with variations in both training and philosophy are used. This was done under the assumption that all of them would contain elements of physical and mental training in line with Tang and Posner (2009) AST classification, found to cause improvements in executive control ( Moore and Malinowski, 2009 ; Gothe et al., 2013 ). However, Weiser et al. (1995) suggested that Martial Arts exist on a continuum with more meditative styles on one end, and more combative styles on the other. This suggests that it may be important to consider potential differences in style in various forms of Martial Arts. Further research intends to assess these possible differences, in the hope that it could lead to a greater understanding of the underlying drivers behind the cognitive improvements associated with Martial Arts.

The current research suggests that the alert network of attention differs between people with Martial Arts experience and those without this experience. Whilst this effect was only found in one of the three known attentional networks, it supports previous work which suggests changes in control as a result of taking part in Martial Arts, whilst also extending the research field into populations of neurotypical adults. Further research should seek to replicate this finding, and discover the underlying reasons for the effect solely appearing in the Alert network and not Orienting or Executive. This may help improve our understanding of how activity in different attentional networks can be ‘trainable’ or able to be improved through Martial Arts.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

AJ and PM-B equally contributed to the development, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and manuscript write- up of this research.

This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council Doctoral Training Center (ESRC DTC) from United Kingdom, grant number ES/J500197/1.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer DG and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexander Kelly and Lauren Green for their help collecting data. They would also like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments on the manuscript.

Bavelier, D., and Davidson, R. J. (2013). Brain training: games to do you good. Nature 494, 425–426. doi: 10.1038/494425a

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Boot, W. R., Kramer, A. F., Simons, D. J., Fabiani, M., and Gratton, G. (2008). The effects of video game playing on attention, memory, and executive control. Acta Psychol. 129, 387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.09.005

Carriere, J. S., Cheyne, J. A., Solman, G. J., and Smilek, D. (2010). Age trends for failures of sustained attention. Psychol. Aging 25, 569–574. doi: 10.1037/a0019363

Chamberlain, S. R., Müller, U., Blackwell, A. D., Clark, L., Robbins, T. W., and Sahakian, B. J. (2006). Neurochemical modulation of response inhibition and probabilistic learning in humans. Science 311, 861–863. doi: 10.1126/science.1121218

Clark, L., Iversen, S. D., and Goodwin, G. M. (2002). Sustained attention deficit in bipolar disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 180, 313–319. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.4.313

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Deary, I. J., Corley, J., Gow, A. J., Harris, S. E., Houlihan, L. M., Marioni, R. E., et al. (2009). Age-associated cognitive decline. Br. Med. Bull. 92, 135–152. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp033

Diamond, A., and Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science 333, 959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1204529

Diamond, A., and Ling, D. S. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.11.005

Dorbath, L., Hasselhorn, M., and Titz, C. (2011). Aging and executive functioning: a training study on focus-switching. Front. Psychol. 2:257. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00257

Durston, S., Mulder, M., Casey, B. J., Ziermans, T., and van Engeland, H. (2006). Activation in ventral prefrontal cortex is sensitive to genetic vulnerability for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.020

Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Fossella, J., Flombaum, J. I., and Posner, M. I. (2005). The activation of attentional networks. Neuroimage 26, 471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004

Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Sommer, T., Raz, A., and Posner, M. I. (2002). Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 14, 340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886

Fan, J., and Posner, M. (2004). Human attentional networks. Psychiatr. Prax 31(Suppl. 2), S210–S214. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828484