Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

"Nowadays" vs "today"

I'm taking an English academic writing course. My teacher recommended using today as it is more accepted compared to nowadays . I asked her if this is accepted in American English (she's from US) or in general. She said in general . Then I asked her why it was recommended. Her reasoning was:

When you publish an article your audience will be the whole world and not everyone in this world is a native English speaker, so it is recommended to use simple English .

Is replacing nowadays by today really recommended? I'm looking for a source that can prove or disprove the above statement. I am a non-native English speaker myself, trying to learn English from different sources.

- word-choice

- 3 Even if a non-native English speaker did not know what nowadays means, I think it would be quite easy for them to figure it out from the component morphemes. – Peter Shor Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 11:58

- 4 When today has the meaning of "at the present time" / "in this day and age", either can be used. But when today has the meaning of "this very day" you cannot use nowadays instead. – None Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 13:13

- 1 I agree that technical writing (or any writing that is intended to be widely read by non-native speakers) should be in simple English. So--instead of disputing "nowadays"--you could be looking for other examples in your writing where it could be done more simply. – GEdgar Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 13:32

- I agree with most of the comments. I use 'today', but I still hear nowadays a lot. I think it's because I live in a non native English speaking country. – user91071 Commented Sep 11, 2014 at 3:33

- That is an individual opinion and not worth much. I would forget what your teacher said about "today" and "nowadays", it is not tenable. – rogermue Commented Jun 26, 2015 at 8:57

6 Answers 6

Nowadays and today are both perfectly acceptable. You could also say these days , in recent times and at present or presently . If your teacher prefers that you don't use nowadays I would follow her instructions just because there are so many alternatives and she is the one grading your paper.

- 10 To me, nowadays doesn't seem formal enough to put in a paper. I would use it in conversation, or maybe a news article, but never in a formal paper. I'm not sure if that's just how I've been taught, however. – Brendon Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 11:55

- 1 According to the Economist style guide (British English), presently should not be used in this context as presently means "after a short time" - "currently" should be used instead. I would agree with the other suggestions though. I tend to agree with Brendon that "nowadays" doesn't seem formal enough for an academic paper. – Matt Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 12:24

- @ Matt: The usage of "presently" is much disputed and to most people I assume "presently" means "now". −−− learnersdictionary.com/search/presently −−− en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_English_words_with_disputed_usage – None Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 13:14

- 1 I wouldn't say nowadays is less formal than today . I just think that nowadays nowadays is not as widely used as today . An ngram shows a decline in the use of nowadays in the 30's and an increase in the use of today around the same period, and stable since. – None Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 13:16

- @Matt & Laure: "Presently" is one of those words that English teachers and other pedants say means one thing but most people use to mean something else. I'd avoid using it to mean "nowadays" in an English paper, but otherwise I routinely use it with that meaning. I suspect the average reader would pause on reading a usage with the English-teacher definition, like "I shall return your pencil presently", and would have to guess the meaning from the context. – Jay Commented Oct 31, 2011 at 14:38

Based on my experiences editing academic papers and professional articles from both native and non-native speakers of English, the word "nowadays" is a signal that the writer is not a native English speaker. I see it most commonly used by Chinese speakers.

Both "nowadays" and "today" are acceptable. However, when editing, I generally remove any such term. If you're using the present tense, you imply "now."

For example: "Nowadays, people act as if they have more money than they really do." This sentence means and implies the same thing as "People act as if they have more money than they really do." Here, the word "nowadays" is redundant, resulting in loose and dull writing.

My recommendation: Rather than struggle with "nowadays" and "today," revise your sentences so that neither is needed.

- 2 I'm not sure if I agree with your example. Adding 'Nowadays' conveys the additional meaning of some kind of contrast with the past. Of course, if this additional meaning isn't intended then I agree 100% that 'nowadays' is redundant. – tinyd Commented Jan 13, 2012 at 13:31

- As someone who goes through hordes of technical documentation, I utterly see this in almost every other thing I do. I had not realized it until I read this statement how true it is. I correct things from multiple sources from across the world in a huge variety of fields (healthcare, oil & gas, social good, charities, large industries, retail, IT-services, etc.) and I can now see the distinction here. – Tucker Commented Sep 6, 2018 at 15:26

I'd agree with Mark that, for this class, you should follow the teacher's direction if you hope to get good grades on your papers!

But long term, it's a tough question. "Nowadays" is not a very commonly used word any more. On the other hand, "today" is most often understood to me "in the current 24-hour period", so there could be times when using "today" to mean "the current era" could create an ambiguity. Usually the intent would be apparent from the context, but not necessarily. As I think about it, this is rather tricky. If someone said, "The stock market is falling today", I think most people would understand him to mean "in this 24-hour period". But if he said, "The economy is doing poorly today", people would understand him to mean "in the last few years".

I'd generally opt for "currently", "at the present time", "these days", etc.

- Not a very commonly used word?! Nonsense, I hear it all the time, nowadays. – Jez Commented Nov 1, 2011 at 17:14

- 1 Well, I don't hear it very often, and of course the standard of good English is what is used by MY friends and associates. :-) – Jay Commented Nov 2, 2011 at 17:43

- Do what teacher says just to get a good grade? Anymore, people have no backbone :p – Eugene Seidel Commented Apr 24, 2012 at 13:59

- @Eugene If a teacher or a boss says, "Do X", then assuming it's not illegal or immoral, sure, I'll do it to get along for the time being. I'm not going to make something the rule for my life just because a teacher I had 20 years ago said so. :-) – Jay Commented Apr 24, 2012 at 14:12

The word creates a sense of awkwardness. It detracts from the intent of the statement because the reader has to stop and mull the intention of the writer. In academic writing your job is to communicate quickly and effectively. Anything that detracts from that purpose should be rewritten. Do you see this used in the article you are responding to? If you do, how is it used? When? In most cases my students can not find this usage in articles. I then walk them through a revision process to see how to make a statement stronger and clarify the meaning.

"Nowadays." while standard English, has a colloquial ring. "Today" is preferred in academic writing. Academic writing requires a more elevated register, which the adverb "nowadays" does not meet. The matter is simple: read published articles in academia and compare the frequency of "nowadays" versus "today." "Nowadays"is the common expression used by my high school students. If you adhere to the "usage reigns" approach in linguistics, then there is little more to say.

Yes, that's right: "nowadays" is technically correct, but colloquial. It is perfectly acceptable in oral speech, but it strikes the wrong tone in written English -- because it is so informal or colloquial. The student should follow the teacher's recommendation not because that is the way to improve a grade, but because the teacher is right.

- But "today" and "nowadays" don't have the same meaning. "Today" can mean "this very day" in a different context. "Nowadays" is more synonymous with "currently". Would you consider expanding your answer to explain that? – filistinist Commented Sep 9, 2017 at 23:48

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged word-choice adverbs or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Introducing an accessibility dashboard and some upcoming changes to display...

- We've made changes to our Terms of Service & Privacy Policy - July 2024

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- How bright would nights be if the moon were terraformed?

- Are story points really a good measure for velocity?

- Solar System Replacement?

- If pressure is caused by the weight of water above you, why is pressure said to act in all direction, not just down?

- When can a citizen's arrest of an Interpol fugitive be legal in Washington D.C.?

- What does וַיַּחְשְׁבֶ֥הָ really mean in Genesis 15:6, literally and conceptually?

- If a planet or star is composed of gas, the center of mass will have zero gravity but immense pressure? I'm trying to understand fusion in stars

- Does wisdom come with age?

- On Adding a Colorized One-Sided Margin to a Tikzpicture

- Best (safest) order of travel for Russia and the USA (short research trip)

- How to use Mathematica to plot following helix solid geometry?

- Why do commercial airliners go around on hard touchdown?

- How do we know that the number of points on a line is uncountable?

- What happens if your child sells your car?

- When are these base spaces isomorphic?

- Refereeing papers by people you are very close to

- Litz Limitations

- In Norway, when number ranges are listed 3 times on a sign, what do they mean?

- unable to mount external hard disk in 24.04

- What does "you must keep" mean in "you must keep my covenant", Genesis 17:9?

- Connect electric cable with 4 wires to 3-prong 30 Amp 125-Volt/250-Volt outlet?

- Is there such a thing as icing in the propeller?

- Splitting a Number into Random Parts

- Typescript Implementation for a fully typed map with all keys from a string union type and values to be function with return type specific to key

- Free Resources

- 1-800-567-9619

- Subscribe to the blog Thank you! Please check your inbox for your confirmation email. You must click the link in the email to verify your request.

- Explore Archive

- Explore Language & Culture Blogs

What’s Wrong With Nowadays? Posted by Gary Locke on Dec 9, 2021 in English Language

Image by Dmitry Abramov from Pixabay

There are English words that, the moment I see them, I want to scream my head off. We have adopted some words from everyday conversation and made them such common expressions that many have forgotten how unsophisticated they sound. One such word is nowadays , and I have begun to see it in writing a lot. If you use it in writing, I am here to beg you to stop.

Meaning and Spelling

First, let’s begin by defining the word and how it is properly spelled and used. Nowadays is an adverb that means “currently” or “at the present time”. We use it in comparison with the past. Its use goes as far back as the 14 th century when it was a three-word phrase spelled as now a dayes . It is now always spelled as one word – nowadays. It isn’t ever hyphenated.

It is also a word typically used in casual conversation. “Everybody ditched their vinyl records for compact discs back in the 90s, but nowadays it seems like everyone wants vinyl again.” And in conversation is exactly where nowadays belongs.

Properly speaking, nowadays isn’t slang. You can find it in the dictionary and there’s even a proper rule for it. If used at the beginning of a sentence you must follow the word with a comma – “Nowadays, you can’t find a parking space on a city street.”

It is also, however, a very informal word.

Let’s Try Something Else, Shall We?

The reason that I cringe every time I read the word nowadays is that we need to understand the difference between formal and informal writing. If you are writing in social media, or in a text, casual writing is fine. But too often we are blurring the boundaries between what is colloquial and what is stylistically proper. We are losing something precious in our culture if we can’t make that distinction.

It’s perfectly fine to have your own voice when writing, but you should know that people form opinions of you from your style. If you are making a serious point in an essay, or even in an email to a friend or colleague, you want to make that point eloquently and with force. To use an informal word diminishes your language’s power.

Good writers struggle to find the exact word that will convey their meaning. And, no, not everything you write needs such scrutiny. You’re not expected to be Hemingway. Still, if you find yourself writing about something that you want to be taken seriously, look for some word other than the one that you would use in a casual conversation with a sibling or old friend.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Gary Locke

Gary is a semi-professional hyphenate.

Adelaide Dupont:

Do people use NOW or RIGHT NOW when it comes to the vinyl sentence [or sentences like that]?

We really do seem to be the five people we have casual conversations with…

Gary Locke:

@Adelaide Dupont Hi Adelaide, Speaking as an editor, I would probably change the sentence to read, “Everybody ditched their vinyl records for compact discs back in the 90s, but today it seems like everyone wants vinyl again.” However, substituting “now” for nowadays would be perfectly acceptable. Cheers! Gary

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Nowadays , these days or today ?

We can use nowadays, these days or today as adverbs meaning ‘at the present time, in comparison with the past’:

I don’t watch TV very much nowadays . There’s so much rubbish on. It’s not like it used to be.

Young people nowadays don’t respect their teachers any more.

Take care to spell nowadays correctly: not ‘nowdays’.

These days is more informal:

These days you never see a young person give up their seat for an older person on the bus. That’s what I was taught to do when I was a kid.

Pop singers these days don’t seem to last more than a couple of months, then you never hear of them again.

Today is slightly more formal:

Apartments today are often designed for people with busy lifestyles.

We can use today , but not nowadays or these days , with the possessive ’s construction before a noun, or with of after a noun. This use is quite formal:

Today’s family structures are quite different from those of 100 years ago.

The youth of today have never known what life was like without computers.

We don’t use nowadays, these days or today as adjectives:

Cars nowadays / these days / today are much more efficient and economical.

Not: The nowadays cars / The these days cars / The today’s cars …

Word of the Day

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

an area of coral, the top of which can sometimes be seen just above the sea

Robbing, looting, and embezzling: talking about stealing

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

To add ${headword} to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add ${headword} to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Nowadays or Now a Days – How to Write Nowadays

Home » Nowadays or Now a Days – How to Write Nowadays

As languages age, they evolve to match usage trends and broad cultural shifts. At the word level, this sometimes means that spelling changes, or that phrases containing multiple words are condensed into a single word, often through compounding.

In one prominent example, the word nowadays was originally a three-word phrase, now a dayes , from the 14th century.

Today, however, it almost always appears as a single word. But is this shortening a mistake, or does it represent the healthy and necessarily evolution of English? Continue reading to discover whether you should use nowadays or stick with now a days .

What is the Difference Between Nowadays and Now a Days?

In this post, I will compare nowadays vs. now a days . I will outline when it is appropriate to use each spelling. Plus, I will demonstrate the use of a memory tool that you can use to help you remember whether to use nowadays or now a days in your own writing.

When to Use Nowadays

See the sentences below for examples,

- Nowadays, people don’t build cars like the ’63 Corvette coupe anymore.

- Nowadays, the domination of the MacBook Pro in an increasingly competitive ultrabook space is no longer taken as a given.

- My perspective on world affairs is quite different nowadays than it was even a few short years ago.

- These should be graded outward and downward from the swamp’s wettest areas. Then lay drainage “tiles”—nowadays large sections of plastic pipe are used—in the trenches. – The Wall Street Journal

When to Use Now a Days

According to the Oxford English Dictionary , the first recorded use of this word was in 1362. It originates from a Middle English phrase that was originally written as three words, forming nou A dayes .

In its first 100 or so years of use, a few spellings existed, including nou A dayes, nou adaies, now a dayes, nowadayes, etc. After some time, a hyphenated version that more resembles the phrase we see today began to gain ground: now-a-days .

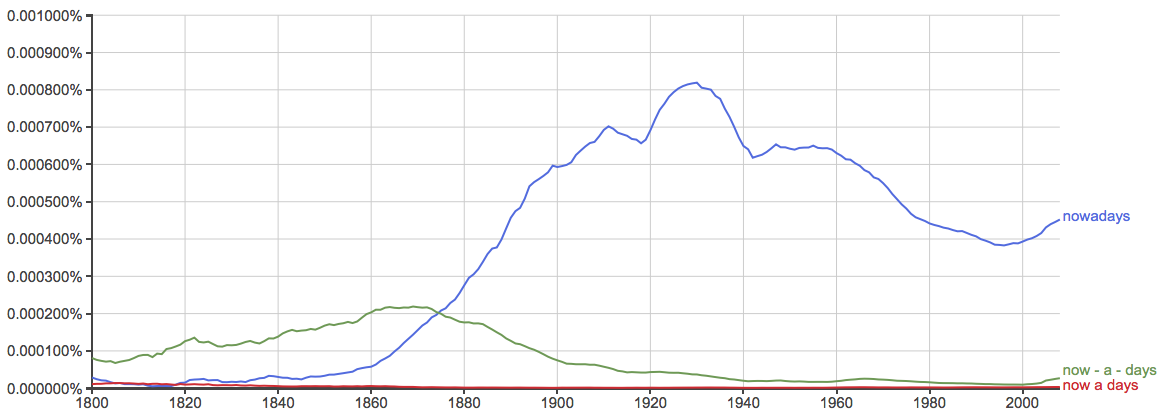

Today, however, the term is invariably combined into a single word without spaces. The following graph shows the frequency of nowadays vs. now a days vs. now-a-days in contemporary English.

Of course, this graph only looks at published English sources since the year 1800, so it is not scientific, or exhaustively accurate. It still clearly shows that the single word nowadays is the standard variant of this phrase.

Trick to Remember the Difference

For a reminder that nowadays is the correct version, remember that its synonyms currently and presently are also single words. This should make it easy for you to keep these words straight in your mind.

Is it nowadays or now a days? The adverb nowadays used to be a three-word phrase several centuries ago, but at least since 1880, writers have shortened it into a single word.

- The single word nowadays is the favored spelling in Modern English.

- Now a days is no longer considered correct.

- The hyphenated now-a-days has also fallen out of use.

Since its synonyms currently and presently are also a single word, it should be no trouble to remember to choose nowadays over now a days .

Remember, you can always check this site for a quick refresher, or any time you have questions about writing and language.

Have a thesis expert improve your writing

Check your thesis for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Common errors

- Is It *Now a Days or Nowadays? | Meaning & Spelling

Is It *Now a Days or Nowadays? | Meaning & Spelling

Published on 25 November 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on 23 August 2023.

Nowadays is an adverb meaning ‘at present’ or ‘in comparison with a past time’.

‘Now a days’, written with spaces, is sometimes used instead of nowadays . However, this is not correct and should be avoided. Other variants such as ‘now-a-days’, ‘now days’, ‘nowdays’, and ‘nowaday’ are also wrong.

- Now a days , many people work from home.

- Nowadays , many people work from home.

- April used to work for a large firm, but now a days she runs a small legal practice .

- April used to work for a large firm, but nowadays she runs a small legal practice.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

How to use nowadays in a sentence, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Nowadays is an adverb meaning ‘at the present time’. It’s used to draw a comparison between the present and the past. When used at the start of a sentence, nowadays is followed by a comma .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or writing rules make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Academic Writing

- Misplaced modifiers

- Parallel structure

- Passive voice

- Transition words

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Some synonyms for nowadays include:

- At this time

- In this day and age

Yes, nowadays is an adverb meaning ‘at present’ or ‘in comparison with the past’. It’s always written as one word (not as ‘now a days’).

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, August 23). Is It *Now a Days or Nowadays? | Meaning & Spelling. Scribbr. Retrieved 5 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/common-errors/nowadays/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, *lable or label | correct spelling & meaning, *truely or truly | correct spelling & meaning, is it whoa or *woah | meaning, spelling & examples.

What are You Looking for?

- Writing Task 1

- Writing Task 2

Should You Start an IELTS Essay with “Nowadays”?

As an IELTS instructor with over 20 years of experience, I often get asked about the “magic formula” for a high-scoring essay. One common question is whether starting an essay with “Nowadays” is a good idea. While it might seem like a harmless phrase, it’s essential to understand the nuances of its usage in IELTS writing.

Table of Contents

- 1 The Problem with “Nowadays”

- 2.1 For Introducing Current Trends:

- 2.2 For Highlighting Changes Over Time:

- 3 Focusing on a Strong Opening

- 5 Key Takeaways

The Problem with “Nowadays”

“Nowadays” is a common transition word used to introduce a current trend or situation. However, it’s often overused and can make your writing sound clichéd and lacking in originality. Examiners are looking for fresh and engaging language that demonstrates a strong command of vocabulary and grammar.

Alternatives to “Nowadays”

Instead of relying on “Nowadays,” consider these alternatives that can add sophistication and clarity to your IELTS essays:

For Introducing Current Trends:

- In recent years/times/decades: This phrase effectively conveys a sense of current relevance without sounding overused.

- The 21st century has witnessed…: This structure is more formal and highlights the significance of the issue in a broader context.

- Currently/Presently: These are simple yet effective alternatives for stating the current state of affairs.

For Highlighting Changes Over Time:

- Over the past few decades, there has been a significant shift in…: This structure emphasizes a gradual development.

- …has become increasingly prevalent/common/important.: This highlights the growing relevance of a particular trend.

Focusing on a Strong Opening

Remember, the key to a successful IELTS essay lies in presenting a clear and well-structured argument. Instead of depending on phrases like “Nowadays,” focus on:

- A strong thesis statement: Clearly state your position on the essay topic in the introduction.

- Providing context: Briefly explain the background or significance of the issue.

- Engaging the reader: Use thought-provoking questions or insightful observations to capture the examiner’s attention.

Instead of: Nowadays, technology has a significant impact on education.

Try: The 21st century has witnessed a dramatic integration of technology into education, transforming the way students learn and interact with knowledge.

Key Takeaways

While “Nowadays” might seem like a convenient starting point, it’s best to avoid it in your IELTS essays. Utilize a variety of vocabulary and grammatical structures to express yourself clearly and effectively. Remember, a successful essay showcases your language proficiency and analytical skills. By focusing on a strong overall structure and engaging content, you’ll be well on your way to achieving your desired IELTS score.

What Do You Want to Do in the Future? – Conquering the IELTS Speaking Test

How to Practice for IELTS: A Guide from a 20-Year Veteran

How Difficult is it to Get a 6.5 in IELTS Speaking?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Your Name *

Email Address *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Test Resources

TOEFL® Resources by Michael Goodine

Using “nowadays” vs “recently”.

Students often struggle to use “recently” and “nowadays” properly in their TOEFL essays. Here’s a quick guide on recommended usage.

Use “ nowadays ” to talk about the state of the world, as in: “ Nowadays, a lot of people choose to attend university .”

Use “ recently ” to talk about a specific event which happened in the recent past, as in: “ My husband recently decided to study Spanish .”

Word Placement

Both are adverbs. “ Recently ” looks fine at the beginning or end of a sentence. It can also be used in the middle (right beside the verb). As in:

- “ Recently , my husband decided to study Spanish.”

- “My husband recently decided to study Spanish.”

- “My husband decided to study Spanish recently .”

Note the comma in the first sentence.

“ Nowadays ” is usually best at the beginning or end of a sentence. As in:

- “ Nowadays , a lot of people choose to attend university.”

- “A lot of people choose to attend university nowadays .”

Using it in the middle of a sentence is a bit trickier, but it is possible if you use parenthetical commas before and after it, as in:

- “A lot people, nowadays , choose to attend university.”

Sign up for express essay evaluation today!

Submit your practice essays for evaluation by the author of this website. Get feedback on grammar, structure, vocabulary and more. Learn how to score better on the TOEFL. Feedback in 48 hours.

Sign Up Today

- Rules/Help/FAQ Help/FAQ

- Members Current visitors

- Interface Language

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

- English Only

"nowadays" or "currently" to begin an essay?

- Thread starter paddycarol

- Start date Nov 17, 2006

Senior Member

- Nov 17, 2006

SweetSoulSister

I like both sentences, but I wouldn't use them to start my essay. I would rather see something without a comma so soon for the first sentence. Campus marriage has become a growing concern in recent times. It's not incorrect to start with "currently" or "nowadays", but I don't like it. That is just my opinion though. I don't think it is a strict rule.

I don't think you need an introductory word to introduce such a topic. The sentences will read perfectly well without either currently or nowadays. It can safely be assumed that you are talking about the present unless you say differently. Personally, I suspect any opening like that is hiding an un-supported generalisation. How do you know that people are getting more and more concerned about campus marriage, or that children often prefer watching TV to reading? Who says? The place for words such as this is in the body of the essay when you are drawing comparisons between the past and the present. Incidentally, I have seen the word "nowadays" more often in this forum than ever in my life before. Does it hold a particular fascination for non-native students of English? Is it one of the words that English language courses use to explain some peculiarity of English or English-speakers?

No problem paddycarol. I agree Pongo Dude! I have also seen that word a ton! Maybe it's the first hit on the Thesaurus. But I rarely use it myself.

- Nov 18, 2006

Panjandrum wrote:"Incidentally, I have seen the word "nowadays" more often in this forum than ever in my life before. Does it hold a particular fascination for non-native students of English? Is it one of the words that English language courses use to explain some peculiarity of English or English-speakers?" I think that, at least in Spain, "nowadays" is considered by non-native students of English as a "safe", "solid" starting point for a discursive essay. Word order is a nightmare, and an adverb of time gives them a feeling of security...besides it is fascinating to learn that 3 words in our own native language are reduced to 1 in English. On top of that, this word is difficult to spell properly because of the letter "a" in the middle and the "s" at the end, the latter is hard to remember because the translation into Spanish is in singular. Moreover, "nowadays" and "currently" are commonly used to start any discursive essay in our mother tongue, to give a feeling of generalisation. The sentence Campus marriage has become a growing concern in recent times is SO English. Any upper-intermediate student of EFL would have certainly written: "Nowadays, campus marriage is (becoming) an increasing problem". How would you react to that sentence (in terms of language!!)? Is it grammatically correct but not accepted in everyday usage? Would you consider it wrong?

Moderator: EHL, Arabic, Hebrew, German(-Spanish)

As a first sentence of an essay it would strike me as clumsy and non-native. I would only expect "nowadays" with a comma if you were comparing and contrasting two different time periods. Fifty years ago, campus marriage was not even an issue. Nowadays, it is an increasing problem. (Even that isn't the best writing style, but it's acceptable.) Starting an essay with "nowadays" and a comma is just odd.

panjandrum said: Incidentally, I have seen the word "nowadays" more often in this forum than ever in my life before. Does it hold a particular fascination for non-native students of English? Is it one of the words that English language courses use to explain some peculiarity of English or English-speakers? Click to expand...

- Nov 19, 2006

Thanks Karmele - that's really interesting. Your comments reinforce the impression I had formed - as indeed do Elroy's and dimcl's comments from a more native perspective. Do non-natives use nowadays more often than natives? Is this an impression I have formed because I don't use it myself? The word has a long and respectable ancestry in English, based on the examples in the OED (earliest is 1397). It also appears in the British National Corpus 1,568 times.

paddycarol said: Karmele3 said "Moreover, "nowadays" and "currently" are commonly used to start any discursive essay in our mother tongue, to give a feeling of generalisation." Things are the same in China .That's why I felt shocked when I was told it sounded odd to native speakers. Click to expand...

Personally, I suspect any opening like that is hiding an un-supported generalisation. How do you know that people are getting more and more concerned about campus marriage, or that children often prefer watching TV to reading? Who says? Click to expand...

- Nov 23, 2006

To bring this issue back a moment... Everyone has to write this 15-page research project for my religion class at WFU. They have to then send out their papers to the entire class for everyone to read. Here are the first lines of two of these essays: == In this day in age nobody is perfect. == Nowadays when many of us think of the name Confucius, we think of sayings on fortune cookies and a man with a beard. The truth is he was much more than that. == I couldn't believe it when I saw it...someone who goes to a prestigious university actually started an essay with "nowadays." Let it be known, however, that there is very little chance either of these papers gets a good grade. I just felt I had to share this with the viewers of this thread.

- Our Mission

- Code of Conduct

- The Consultants

- Hours and Locations

- Apply to Become a Consultant

- Make an Appointment

- Face-to-Face Appointments

- Zoom Appointments

- Written Feedback Appointments

- Support for Writers with Disabilities

- Policies and Restrictions

- Upcoming Workshops

- Class Workshops

- Meet the Consultants

- Writing Guides and Tools

- Login or Register

- Graduate Writing Consultations

- Thesis and Dissertation Consultations

- Weekly Write-Ins

- ESOL Graduate Peer Feedback Groups

- Setting Up Your Own Writing Group

- Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- Support for Multilingual Students

- ESOL Opt-In Program

- About Our Consulting Services

- Promote Us to Your Students

- Recommend Consultants

- The Three Common Tenses Used in Academic Writing

He explains the author’s intention and purpose in the article.

*He is explaining the author’s intention and purpose in the article.

Both of the sentences above are grammatically correct. However, the tense used in first sentence (present simple) is more common for academic writing than the tense in the second sentence (present progressive). This handout provides the overview of three tenses that are usually found in academic writing.

There are three tenses that make up 98% of the tensed verbs used in academic writing. The most common tense is present simple, followed by past simple and present perfect. These tenses can be used both in passive and active voice. Below are the main functions that these three tenses have in academic writing.

The Present Simple Tense

Present simple is the most common tense in academic writing, and it is usually considered as the “default” unless there is a certain reason to choose another tense (e.g. a sentence contains a past time marker). Some specific functions of present simple include:

|

|

|

| 1) To frame a paper. It is used in introductions to state what is already known about the topic, and in conclusions to say what is now known.

| Scholars a common argument that engineering the most male dominated of all professions. Timing of college enrollment with a number of variables. |

| 2) To point out the focus, main argument, or aim of the current paper.

| This paper the impact of high temperatures on certain species. |

| 3) To make general statements, conclusions, and interpretations about findings of current or previous research. It focuses on what is known now.

| Graduate school as crucial for starting an engineering career because failure at this stage the door to professional engineering careers, and later career trajectory change more difficult the longer it delayed.

|

| 4) To refer to findings from previous studies without mentioning the author’s name. | Children roughly 50-200 mg soil/day [2,3].

|

| 5) To refer to tables or figures.

| Table 1 the structural units. |

| 6) To describe the events or plot of a literary work. This usage has the name “Narrative present”.

| In Mansuji Ibuse’s Black Rain, a child for a pomegranate in his mother’s garden, and a moment later he dead, killed by the blast of an atomic bomb. |

The Past Simple Tense

Generally, past simple is used to refer to actions completed in the past. Some specific functions this tense has in academic writing include:

|

|

|

| 1) To report specific findings of a previous study (usually with the authors’ names in the sentence) to support a general statement. | Probably the most commonly discussed phenomenon in music cognition is the Mozart Effect (this is the general claim). (Specific example) Rauscher and colleagues first this effect in their seminal paper. |

| 2) To describe the methods or data from a completed experiment. | Statistical analyses to determine relationships between variables. |

| 3) To report results of the current empirical study. | The L1-English writers utilized mostly NP- and PP-based bundles (78.3% of types and 77.1% of tokens). |

| 3) After any past time marker. | After the war, Germany to face strong reparations from the allied nations. |

The Present Perfect Tense

Present perfect is usually used when referring to previous research, and since it is a present tense, it indicates that the findings are relevant today. More specifically, this tense might have the following functions:

|

|

|

| 1) To introduce a new topic. Could also be used to introduce a new report or paper.

| There a large body of research regarding the effect of carbon emissions on climate change. |

| 2) To summarize previous research with general subjects (such as “researchers have found…”)

Present perfect places emphasis on rather than on (present simple). | Some studies that girls have significantly higher fears than boys after trauma (Pfefferbaum et al., 1999; Pine and Cohen, 2002; Shaw, 2003).

|

| 3) To point out a “gap” in existing research: to make a connection between the past (what has been found) and the present (how will you add more to the field).

| While these measures to be reliable and valid predictors of what they are measuring, there is little data on how they relate to each other. |

| 4) To describe previous findings without referring directly to the original paper.

| It that biodiversity is not evenly distributed throughout the world. |

Common Questions about Tense in Academic Writing

Question: Can tenses change in the same paragraph or sentence?

Explanation: Yes, there are some times where it is appropriate to switch tense within a paragraph or sentence. However, you have to have a good reason for it. For instance, a shift in time marked by an adverb or prepositional phrase (e.g. since, in 2013, until ) or when you move from general statements to specific examples from research (one of the functions mentioned above).

Question : Are other verb tenses used in academic writing?

Explanation : Yes, although not as common, other tenses are used in academic writing as well. For example, when expressing strong predictions about the future, the future simple tense is used, or when describing events that undergo changes at the time of writing, present progressive is used.

Read the excerpt and notice the tenses used for each verb. Identify the function of each tense as illustrated in the first sentence.

Approximately 10% of the population is diagnosed (present simple, function 4) with dyslexia (Habib, 2000). Specialized testing most often reveals this disability in third grade or later, when there develops an observable differential between reading achievement and IQ (Wenar & Kerig, 2000). This late identification poses severe problems for effective remediation. At the time of diagnosis, poor readers are on a trajectory of failure that becomes increasingly difficult to reverse. Attempts at intervention must both focus on remediation of the impaired components of reading as well as extensive rehabilitation to reverse the growing experience differential.

Educators and researchers are aware of the need for early diagnosis. In response, research investigating early correlates of later reading ability/disability has burgeoned (e.g. Wagner et al., 1997). However, these early reading studies primarily focus on school age children (e.g. Share et al., 1984). To date, only a few studies have focused on the reading trajectories of children younger than preschool, and there is little consistency within the existing studies (e.g. Scarborough, 1990, 1991).

In the current study, we trace the development of the two aspects of the phonological processing deficit in a longitudinal follow-up study of two-year-olds. Shatz et al. (1996, 1999, 2001) investigated the underlying lexical structure in two-year-old children. Although their experiments were tailored to examine early word learning behavior, their study design is uniquely suited to looking at the phonological processing skills of two-year old children as well. In this study, we measure the early reading skills of these same two-year-olds at five to seven years of age in order to determine the predictivity of the early two-year old behaviors for later reading ability.

Adapted from Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Papers. (2009). Ann Arbor, MI: The Regents of the University of Michigan.

Approximately 10% of the population is diagnosed (pres. simp. F4) with dyslexia (Habib, 2000). Specialized testing most often reveals (pres. simp. F4) this disability in third grade or later, when there develops (pres. simp. F4) an observable differential between reading achievement and IQ (Wenar & Kerig, 2000). This late identification poses (pres. simp. F3) severe problems for effective remediation. At the time of diagnosis, poor readers are (pres. simp. F3) on a trajectory of failure that becomes (pres. simp. F3) increasingly difficult to reverse. Attempts at intervention must both focus on remediation of the impaired components of reading as well as extensive rehabilitation to reverse the growing experience differential.

Educators and researchers are (pres. simp. F1) aware of the need for early diagnosis. In response, research investigating early correlates of later reading ability/disability has burgeoned (pres. perf. F1) (e.g. Wagner et al., 1997). However, these early reading studies primarily focus (pres. simp. F3) on school age children (e.g. Share et al., 1984). To date, only a few studies have focused (pres. perf. F3) on the reading trajectories of children younger than preschool, and there is (pres. simp. F3) little consistency within the existing studies (e.g. Scarborough, 1990, 1991).

In the current study, we trace (pres. simp. F2) the development of the two aspects of the phonological processing deficit in a longitudinal follow-up study of two-year-olds. Shatz et al. (1996, 1999, 2001) investigated (past. simp. F1) the underlying lexical structure in two-year-old children. Although their experiments were tailored (past. simp. F1) to examine early word learning behavior, their study design is uniquely suited (pres. simp. F3) to looking at the phonological processing skills of two-year old children as well. In this study, we measure (pres. simp. F2) the early reading skills of these same two-year-olds at five to seven years of age in order to determine the predictivity of the early two-year old behaviors for later reading ability.

The information in this handout is adapted from Caplan, N. (2015). Grammar choices for graduate and professional writers . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Last updated 12/20/2017

Grammar & Style

- Converting Fragments to Full Sentences

- Active and Passive Voice

- Choosing Between Infinitive and Gerund: “To do” or “doing”?

- Choosing the Correct Word Form

- Combining Clauses to Avoid Comma Splices, Run-ons, and Fragments

- Commas, Semicolons, and Colons

- Count vs. Noncount Nouns

- Definite and Indefinite Articles

- Improving Cohesion: The "Known/New Contract"

- Modal Verbs

- Parallel Structure

- Prepositions

- Proper Nouns

- Reducing Informality in Academic Writing

- Run-on Sentences

- Same Form, but Different Functions: Various Meanings of Verb+ing and Verb+ed

- Subject-Verb Agreement

- Using Reduced Relative Clauses to Write Concisely

- Verb Tenses

- Word Order in Statements with Embedded Questions

The Writing Center

4400 University Drive, 2G8 Fairfax, VA 22030

- Johnson Center, Room 227E

- +1-703-993-1200

- [email protected]

Quick Links

- Register with us

© Copyright 2024 George Mason University . All Rights Reserved. Privacy Statement | Accessibility

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an introduction paragraph , how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an essay introduction:

- Start with a Hook : Begin your introduction paragraph with an attention-grabbing statement, question, quote, or anecdote related to your topic. The hook should pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to continue reading.

- Provide Background Information : This helps the reader understand the relevance and importance of the topic.

- State Your Thesis Statement : The last sentence is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and directly address the topic of your essay.

- Preview the Main Points : This gives the reader an idea of what to expect and how you will support your thesis.

- Keep it Concise and Clear : Avoid going into too much detail or including information not directly relevant to your topic.

- Revise : Revise your introduction after you’ve written the rest of your essay to ensure it aligns with your final argument.

Here’s an example of an essay introduction paragraph about the importance of education:

Education is often viewed as a fundamental human right and a key social and economic development driver. As Nelson Mandela once famously said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It is the key to unlocking a wide range of opportunities and benefits for individuals, societies, and nations. In today’s constantly evolving world, education has become even more critical. It has expanded beyond traditional classroom learning to include digital and remote learning, making education more accessible and convenient. This essay will delve into the importance of education in empowering individuals to achieve their dreams, improving societies by promoting social justice and equality, and driving economic growth by developing a skilled workforce and promoting innovation.

This introduction paragraph example includes a hook (the quote by Nelson Mandela), provides some background information on education, and states the thesis statement (the importance of education).

This is one of the key steps in how to write an essay introduction. Crafting a compelling hook is vital because it sets the tone for your entire essay and determines whether your readers will stay interested. A good hook draws the reader in and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

- Avoid Dry Fact : Instead of simply stating a bland fact, try to make it engaging and relevant to your topic. For example, if you’re writing about the benefits of exercise, you could start with a startling statistic like, “Did you know that regular exercise can increase your lifespan by up to seven years?”

- Avoid Using a Dictionary Definition : While definitions can be informative, they’re not always the most captivating way to start an essay. Instead, try to use a quote, anecdote, or provocative question to pique the reader’s interest. For instance, if you’re writing about freedom, you could begin with a quote from a famous freedom fighter or philosopher.

- Do Not Just State a Fact That the Reader Already Knows : This ties back to the first point—your hook should surprise or intrigue the reader. For Here’s an introduction paragraph example, if you’re writing about climate change, you could start with a thought-provoking statement like, “Despite overwhelming evidence, many people still refuse to believe in the reality of climate change.”

Including background information in the introduction section of your essay is important to provide context and establish the relevance of your topic. When writing the background information, you can follow these steps:

- Start with a General Statement: Begin with a general statement about the topic and gradually narrow it down to your specific focus. For example, when discussing the impact of social media, you can begin by making a broad statement about social media and its widespread use in today’s society, as follows: “Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of users worldwide.”

- Define Key Terms : Define any key terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to your readers but are essential for understanding your argument.

- Provide Relevant Statistics: Use statistics or facts to highlight the significance of the issue you’re discussing. For instance, “According to a report by Statista, the number of social media users is expected to reach 4.41 billion by 2025.”

- Discuss the Evolution: Mention previous research or studies that have been conducted on the topic, especially those that are relevant to your argument. Mention key milestones or developments that have shaped its current impact. You can also outline some of the major effects of social media. For example, you can briefly describe how social media has evolved, including positives such as increased connectivity and issues like cyberbullying and privacy concerns.

- Transition to Your Thesis: Use the background information to lead into your thesis statement, which should clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay. For example, “Given its pervasive influence, it is crucial to examine the impact of social media on mental health.”

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other type of academic writing. It appears near the end of the introduction. Here’s how to write a thesis statement:

- Identify the topic: Start by identifying the topic of your essay. For example, if your essay is about the importance of exercise for overall health, your topic is “exercise.”

- State your position: Next, state your position or claim about the topic. This is the main argument or point you want to make. For example, if you believe that regular exercise is crucial for maintaining good health, your position could be: “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining good health.”

- Support your position: Provide a brief overview of the reasons or evidence that support your position. These will be the main points of your essay. For example, if you’re writing an essay about the importance of exercise, you could mention the physical health benefits, mental health benefits, and the role of exercise in disease prevention.

- Make it specific: Ensure your thesis statement clearly states what you will discuss in your essay. For example, instead of saying, “Exercise is good for you,” you could say, “Regular exercise, including cardiovascular and strength training, can improve overall health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

Examples of essay introduction

Here are examples of essay introductions for different types of essays:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

Topic: Should the voting age be lowered to 16?

“The question of whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 has sparked nationwide debate. While some argue that 16-year-olds lack the requisite maturity and knowledge to make informed decisions, others argue that doing so would imbue young people with agency and give them a voice in shaping their future.”

Expository Essay Introduction Example

Topic: The benefits of regular exercise

“In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. From improving physical health to boosting mental well-being, the benefits of exercise are numerous and far-reaching. This essay will examine the various advantages of regular exercise and provide tips on incorporating it into your daily routine.”

Text: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“Harper Lee’s novel, ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ is a timeless classic that explores themes of racism, injustice, and morality in the American South. Through the eyes of young Scout Finch, the reader is taken on a journey that challenges societal norms and forces characters to confront their prejudices. This essay will analyze the novel’s use of symbolism, character development, and narrative structure to uncover its deeper meaning and relevance to contemporary society.”

- Engaging and Relevant First Sentence : The opening sentence captures the reader’s attention and relates directly to the topic.

- Background Information : Enough background information is introduced to provide context for the thesis statement.

- Definition of Important Terms : Key terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to the audience or are central to the argument are defined.

- Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement presents the main point or argument of the essay.

- Relevance to Main Body : Everything in the introduction directly relates to and sets up the discussion in the main body of the essay.

Writing a strong introduction is crucial for setting the tone and context of your essay. Here are the key takeaways for how to write essay introduction: 3

- Hook the Reader : Start with an engaging hook to grab the reader’s attention. This could be a compelling question, a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or an anecdote.

- Provide Background : Give a brief overview of the topic, setting the context and stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement : State your thesis, which is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

- Preview the Structure : Outline the main points or arguments to help the reader understand the organization of your essay.

- Keep it Concise : Avoid including unnecessary details or information not directly related to your thesis.

- Revise and Edit : Revise your introduction to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance. Check for grammar and spelling errors.

- Seek Feedback : Get feedback from peers or instructors to improve your introduction further.

The purpose of an essay introduction is to give an overview of the topic, context, and main ideas of the essay. It is meant to engage the reader, establish the tone for the rest of the essay, and introduce the thesis statement or central argument.

An essay introduction typically ranges from 5-10% of the total word count. For example, in a 1,000-word essay, the introduction would be roughly 50-100 words. However, the length can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the overall length of the essay.

An essay introduction is critical in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. To ensure its effectiveness, consider incorporating these key elements: a compelling hook, background information, a clear thesis statement, an outline of the essay’s scope, a smooth transition to the body, and optional signposting sentences.

The process of writing an essay introduction is not necessarily straightforward, but there are several strategies that can be employed to achieve this end. When experiencing difficulty initiating the process, consider the following techniques: begin with an anecdote, a quotation, an image, a question, or a startling fact to pique the reader’s interest. It may also be helpful to consider the five W’s of journalism: who, what, when, where, why, and how. For instance, an anecdotal opening could be structured as follows: “As I ascended the stage, momentarily blinded by the intense lights, I could sense the weight of a hundred eyes upon me, anticipating my next move. The topic of discussion was climate change, a subject I was passionate about, and it was my first public speaking event. Little did I know , that pivotal moment would not only alter my perspective but also chart my life’s course.”

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your introduction paragraph is crucial to grab your reader’s attention. To achieve this, avoid using overused phrases such as “In this paper, I will write about” or “I will focus on” as they lack originality. Instead, strive to engage your reader by substantiating your stance or proposition with a “so what” clause. While writing your thesis statement, aim to be precise, succinct, and clear in conveying your main argument.

To create an effective essay introduction, ensure it is clear, engaging, relevant, and contains a concise thesis statement. It should transition smoothly into the essay and be long enough to cover necessary points but not become overwhelming. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to assess its effectiveness.

References

- Cui, L. (2022). Unit 6 Essay Introduction. Building Academic Writing Skills .

- West, H., Malcolm, G., Keywood, S., & Hill, J. (2019). Writing a successful essay. Journal of Geography in Higher Education , 43 (4), 609-617.

- Beavers, M. E., Thoune, D. L., & McBeth, M. (2023). Bibliographic Essay: Reading, Researching, Teaching, and Writing with Hooks: A Queer Literacy Sponsorship. College English, 85(3), 230-242.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- How to Cite Social Media Sources in Academic Writing?

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

Similarity Checks: The Author’s Guide to Plagiarism and Responsible Writing

Types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid it in your writing , you may also like, how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to structure an essay.

164 Phrases and words You Should Never Use in an Essay—and the Powerful Alternatives you Should

This list of words you should never use in an essay will help you write compelling, succinct, and effective essays that impress your professor.

Writing an essay can be a time-consuming and laborious process that seems to take forever.

But how often do you put your all into your paper only to achieve a lame grade?

You may be left scratching your head, wondering where it all went wrong.

Chances are, like many students, you were guilty of using words that completely undermined your credibility and the effectiveness of your argument.

Our professional essay editors have seen it time and time again: The use of commonplace, seemingly innocent, words and phrases that weaken the power of essays and turn the reader off.

But can changing a few words here and there really make a difference to your grades?

Absolutely.

If you’re serious about improving your essay scores, you must ensure you make the most of every single word and phrase you use in your paper and avoid any that rob your essay of its power (check out our guide to editing an essay for more details).

Here is our list of words and phrases you should ditch, together with some alternatives that will be so much more impressive. For some further inspiration, check out our AI essay writer .