From around the world.

A breaching experiment goes outside our ideas of social norms specifically to see how people will react to the violation of the arbitrary rules of a given situation. These experimental forays arise from the idea that people create social norms themselves without any awareness that they do so and that most individuals need to be shocked out of their ideas of normality to have any meaningful interactions.

An example of "breaching" experimentally is to talk with an acquaintance and interpret his figurative usages literally, to explore the idea that we overuse figurative language to the point where interpretation becomes absurd. Your friend begins with "What's up?" and you reply "The sky." He may end the experimental conversation by saying "You trippin'!" Point out that you're standing and well-balanced, in no danger of tripping. Your friend's attempts to "normalize" the conversation throw light on how he responds to other situations that may puzzle his sense of social normality.

How does john proctor's great dilemma change during the course of the play "the crucible", examples of tone in "thanatopsis", what is the tone of irving's short story "the legend of sleepy hollow", how does connell use suspense in "the most dangerous game", what should the conclusion do in a reflective essay, the talk-line experiment.

When we converse, we also create imaginary barriers, our force fields of comfort we call "personal space." An interesting breach of this is the talk-line. Enlist a compatriot to converse with in a hallway. As the two of you talk, move further away from each other so that you're at least 4 feet apart but keep your eye contact and conversation going. Notice how many people actually "duck" as they go between you as if your conversation has created an actual barrier. Again, they attempt to normalize the situation and re-establish boundaries that social convention has dictated.

Sometimes social norms breach themselves. Eating with hands in a fancy restaurant used to be forbidden, but it's become more trendy with the introduction of different cultural norms. You still can breach restaurant etiquette experimentally. George Carlin, in "Brain Droppings," recommends asking a waiter if the garnish is free, then ordering a large plate of garnish. If you were to try this experiment, the waiter's response, and perhaps your own discomfort in placing the order, would reveal the predispositions you both have, that you must "set" normality in trivial situations, following norms simply because you believe they exist.

Harold Garfinkle, the ethnomethodologist who pioneered breach experimentation, established experiments that invaded both home and business norms. He sent students back to their parental homes to act as renters and into businesses to mistake customers for salesmen. These actions, Garfinkle felt, brought to light automatic responses and the reinforcement of agreed social boundaries.

Redlark — May 18, 2012

It might be interesting to explore how different "norms" are experienced by different people. As a queer woman, here are thoughts on the three norms given above:

1. I've been socialized not to rock the boat, so I feel pressure to race over the door even if it's a nuisance. More importantly, I am now hyperaware of gender - because I assume that a man ostentatiously holding a door for me (if I'm not on crutches or carrying a giant box) is doing it out of gendered "chivalry". This reminds me that as a butch queer woman I am unattractive to straight dudes and often encounter resentment, hostility and ostentatious "gendering" (ie, some dude stares at my breasts really obviously or calls me "honey" in a sarcastic way to remind me that I may "think I'm a man" or think I don't have to look fuckable, but I'm still subject to his gaze ). In general, when a man holds a door for me unnecessarily (when we're both physically capable and fairly young, when I'm not carrying anything, when I am not so close to the door that to fail to hold it would mean to let is slam in my face), I get stressed and upset because I have to stop thinking of myself as "person walking around" and have to start thinking of myself as "person performing femininity and being evaluated by men".

I would argue that this is very different from how a man, a person in a wheelchair, a trans person, etc etc etc, would experience these "norms". The norms are shared, but everyone feels differently about the behavior that the norms generate.

2. To continue, as a butch queer woman, I have been shoved and body-checked by men at random on the sidewalk - or rather "off the sidewalk" - sometimes when there is a group of men taking up the whole sidewalk who do not want to share the sidewalk and sometimes out of what I assume is pure hostility. A man walking close to me and getting in the way makes me nervous because it can be the prelude to an unpleasant, homophobic encounter.

3. And of course, being stared at is experienced in different ways depending on who you are, even though it's always weird and uncomfortable.

D Traver Adolphus — May 18, 2012

I do that all the time. I didn't realize I was a deviant.

Leslee Bottomley Beldotti — May 18, 2012

I conducted my own experiments like this, year ago, when I lived in Chicago.

The most interesting one involved me refusing to look away first whenever I made random eye contact with a male stranger in public. The "norm" is that as a woman, I should always look away first.

The reaction I got depended greatly upon age and race. White men, especially if they were obviously younger than me, would become visibly nervous and look away first. Older white men would attempt to maintain the gaze a bit longer, but would usually relent and look away with some apparent discomfort. Black men, (unless they were teenagers or younger) seemed to perceive my unwillingness to look away first as some type of nonverbal challenge, or even as a sexual advance!

In case you're curious... women, regardless of age or race, would always look away first with little or no hesitation.

I didn't get the opportunity to test this on people of other races beyond black and caucasian.

Marie — May 18, 2012

Reminds me of Mormon humor. Polite, inoffensive, fun for all ages. Not particularly insightful. I'm learning more from the comments.

astrocomfy — May 18, 2012

I guess I thought the norm breaking in the video was that he was holding the door for people who were REALLY far away. What kind of people are you if you slam doors in people's faces if they're right behind you (people of either sex, btw)? But this guy was just holding doors for anyone, especially those that still had quite a distance to travel. And that is what made it awkward and uncomfortable, not that he was holding the door.

Roger Braun — May 18, 2012

This feels like one of the "Well, D'uh!" posts that I don't really like. What is this experiment supposed to tell us? Of course people react irritated when you are irritating. Most of these videos seem like autistic or even psychopathic behavior, so it's easy to imagine how people would react.

The Gaze and Mild Norm Breaching | Hourclass — May 18, 2012

[...] via Sociological Images Norm Breaching. [...]

Janether — May 18, 2012

I had a similar assignment in class, and I chose to trim my toenails in the dining area in my college and while I was watching a musical performed by the college students.

Lunad — May 19, 2012

I actually got into the habit of holding the door for people that are too far away when I was in college and most of the doors were locked, where it was considered a faux pas to close a door behind you when you clearly could have seen that someone was coming. Now I can't break the habit...

Legolewdite — May 19, 2012

Re: the stare - It's my understanding that the gaze contains power (Mulvey worked with this idea extensively...), and that those who see are considered more powerful than those merely seen. So in this culture where power so often exists in the form of an abusive relationship, it's no surprise to me that people become so anxious when this particular norm is transgressed...

Tusconian — May 19, 2012

I think a better discussion would not be people's reactions to deviant behavior, but WHY these behaviors are deviant. People like to chalk things like this up to "people just hate it when other people are nice" or "people overreact to the littlest things like being looked at," but that completely separates the "deviant" behavior from the context it's usually present in when these behaviors come up naturally as opposed to someone doing an experiment. As for being stared at, people usually "stare" (not just look or glance, but stare) for one of 3 reasons: your appearance somehow offends them, they're checking you out, or they're trying to take a peek at whatever you're doing. ALL of those are invasive, uncomfortable feelings. I don't want someone sitting there making me feel like an outcast for whatever I'd done to "look wrong," I don't want some creep ogling me, and I don't want anyone looking over my shoulder at my phone/computer/book/whatever. As for "getting in my way" that bothers and annoys me because obviously, I've got someplace to be. If I'm going to work or class or to meet someone, I don't like being impeded. I'm sure the woman with the double stroller would be even more irritated, because she has to navigate an SUV sized barge with toddlers in it around who she perceives as some doof who isn't paying attention. Having someone walk so close that you'd need to move off the sidewalk is just rude. Intentional or not, it screams "I'm more important and more worthy of this sidewalk than you are!" Holding the door is a little more hard to pin down, because it could just as easily be someone who misjudged distance. But, how often do you go online and see self-proclaimed nice guys acting like they deserve fanfare for simply not slamming a door in a woman's face, and blaming feminism for some completely fabricated story where a women screamed at him for being polite. Guys who hold doors for me at inappropriate times just as often as not do it in a dramatic way, with an ear to ear grin and maybe even a flourish ("after YOU, milady!"). It reads not as "look, I have enough social awareness not to be rude to you," but as "look at ME, I am not like those OTHER guys who disrespect woman and forgot chivalry! I hold DOORS and treat women like the delicate flowers on pedestals that they are! Where is my trophy?" Again, it is just as often someone goofing up and misjudging distance, but when it is often enough beyond simple manners, but showing off, it's suspicious.

Norms are sometimes completely fabricated, but just because something is a norm and sometimes norms are silly or oppressive doesn't mean norms in and of themselves are silly or oppressive. They should be questioned, but I don't know that this guy is questioning the right norms. He just seems like he's harassing people because it's funny to make them uncomfortable, without really considering WHY they're uncomfortable.

Barney — May 19, 2012

What we can't tell from the videos is how much people are made uncomfortable by the fact that norms are being broken, and how much these norms come about because there are other reasons that the norm-breaking behaviours make people uncomfortable.

Resources and Ideas « Q — August 3, 2016

[…] Aug3 by mstrongheart Norm Breaching: Social Responses to Mild Deviance […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About Sociological Images

Sociological Images encourages people to exercise and develop their sociological imaginations with discussions of compelling visuals that span the breadth of sociological inquiry. Read more…

Posts by Topic

Subscribe by email.

CC Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

Break a Norm Project

- March 9, 2022

- No Comments

- Project-Based Learning , sociology

Do you ever get bored of going through the same cycle each week? Outside of work, this often looks like doing laundry and grocery shopping. Honestly, this is no way to relax on the weekend, but there is no other time to do these tasks. Thus, time outside of work is often restful but not very exciting. Sadly, this is also how many students feel in school. For them, it means following a carefully dictated schedule. Upon entering class, it means sitting in a specific spot, raising a hand to talk, and following a teacher’s request. Students follow the norms because of set expectations. The majority of students do not want to break the rules or upset authority figures. Thus, understanding a unit on crime and deviance can be challenging. To help appropriately allow students to experience the content, the Break a Norm Project will be perfect to use!

Break a Norm Project

It is fantastic to have a classroom full of students who want to do well academically and follow the rules. Honestly, this makes the lives of teachers easier. However, this aspect can cause students to struggle to understand crime and deviance in Sociology class. Now, no teacher wants to force students to start breaking laws and purposely get into trouble. Additionally, no teacher wants to encourage students to act out. However, there are creative ways to help students relate to the content!

The Break a Norm project is highly engaging! Honestly, it will be a project students always remember. The purchase includes the assignment, examples, and a rubric for easy grading. Students will see creative ways to break a norm without violating real law by looking at the examples. For instance, this may be skipping instead of walking or sitting at a teacher’s desk in the middle of a lesson. Ultimately, students will break a norm but do so legally.

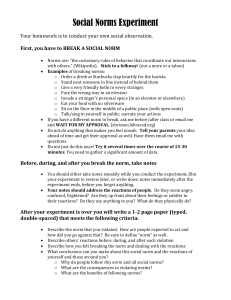

Project Components

The Break a Norm Project includes five components. First, students write a statement of the problem, defining the norm they plan to violate and how it acts as a mechanism of social control. Then, students will explain why they are breaking the norm. Second, they will write a hypothesis. They will describe the range of reactions that others will have due to the violation. Third, they will describe the setting. This allows them to think about where the norm violation will occur and who will observe. Fourth, students will describe the incident. This will let them explain what happened. Lastly, students will complete a summary and interpretation. They will explain how it felt to violate the norm and receive reactions of those in society. Essentially, this project will allow students to gain a deeper understanding of crime and deviance.

Accountability

This project is a way to help students understand what it feels like to break a norm. However, it does not involve doing something to get arrested or into serious trouble. Therefore, it is essential to stress the importance of selecting a societal norm that is school appropriate. Ultimately, students are responsible for their actions. Hence, it is valuable to spend time reviewing the included examples together. By doing this, they will get a feel for what is acceptable and not.

Teacher Benefits of the Break a Norm Project

As a secondary Social Studies teacher, I understand the lack of available resources. Additionally, it is hard to develop creative lessons with so many different preps. Therefore, I create projects that are teacher tested and student approved. This means that I utilize the Break a Norm project each year. Specifically, I reflect on my students and their results to create comprehensive plans driven by proven results. I even provide FREE updates as I continuously reflect on lessons. As a teacher, I know how stressful life can be. Thus, all of my products are organized for teachers and engaging for students.

The Break a Norm Project is a powerful way to help students understand crime and deviance. It will allow students to see what it is like to go against the norm and the results. Ultimately, this will be a project students never forget!

If you do not want to miss any of the upcoming lessons, join my email list to be notified of all the interactive lessons coming up! By joining the email list, you will also receive a Final Sociology Project FREEBIE for blog exclusive subscribers!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

JOIN MY LIST!

Copyright © 2024 passion for social studies | terms and conditions.

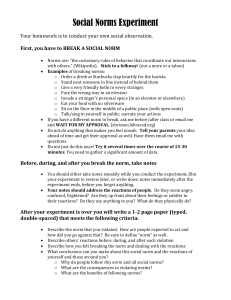

Guidelines for Write-up of

Breaking a Social Norm Assignment

(With thanks to Eells and Unnithan in Kain and Neas , 1993, pp. 55-56.)

The following format is to be followed as you write up this exercise. Please note that this is a skeletal outline and is intended to help you decide what information to include in your report. Be sure to cover all of these points, but don’t feel that you are limited to them. Elaborate and be creative where you can. Incorporate as much as you can from your learning about sociology in everyday settings.

This report should be 2-5 pages in length, typed and double-spaced. Good grammar and sentence structure are expected.

The format to use:

1. Statement of the Problem

A. Define the norm you will violate.

B. Describe briefly how this norm acts as a mechanism of social control.

C. Describe what you will do to violate the norm.

2. Hypothesis

A. Describe the range of possible reactions others will have to the violation of this norm.

B. What do you predict the major reaction will be?

3. Describe the setting

A. Physical—where is the norm violation taking place?

B. Social—How many and what types of persons are observing?

4. Describe the incident—tell what happened.

5. Summary and Interpretation

A. How did you feel as you were violating the norm?

B. Why did you feel the way you did?

C. Did people react the way you expected? Explain.

D. Did you encounter any difficulties in carrying out your assignment?

E. What, if anything, did you learn about how norms exercise social control?

F. Any other pertinent observations.

Norm Violation Video Presentation

How to Cite

Download citation.

Download this resource to see full details. Download this resource to see full details.

Usage Notes

Learning goals and assessments.

Learning Goal(s):

- 1) To reinforce course concepts (such as norm, folkway, informal and formal sanctions, and deviance) and provide students with an opportunity to demonstrate their understanding.

- 2) To allow for the application of the steps in the research process (including collection and analysis of primary data).

- 3) To initiate personal growth though students developing a greater understanding of their comfort levels with conformity and deviance.

Goal Assessment(s):

- Each student demonstrates their achievement of Goal #1 though the inclusion and correct usage of course concepts and terms within the video presentation.

- Goal #2 is achieved through students clearly describing within the video their research question and research methods, and then explaining the data they collected and the logical conclusions that they reached.

- Goal #3 is demonstrated by each student taking a turn, as part of the conclusion of the video, to thoughtfully reflect on what the experience of breaking the norm was like for them personally and how the project affected their perspective on social norms.

When using resources from TRAILS, please include a clear and legible citation.

Similar Resources

- Medora W. Barnes, Norm Violation Video Presentation , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Marcia Ghidina, Using Ma Vie en Rose to Teach about Gender Norms and Socialization , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: TRAILS Featured Resources

- Laura Workman Eells, N. Prabha Unnithan, Technique 31: Norm Violation, Deviance, Labeling, Folkways, Mores , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Joanna S. Hunter, Seeing Gender: Using a Gender Journal and Term Paper to Teach the Sociology of Gender , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Jeffrey S Debies-Carl, Introduction to Qualitative Analysis: A Coding Exercise Using the Material Culture of College Students , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Mary Nell Trautner, Elizabeth Borland, Using the Sociological Imagination to Teach about academic Integrity , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Martha A. Easton, Norms, Deviance, and Social Control , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: TRAILS Featured Resources

- Miriam W. Boeri, Deviance and Social Control , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Janet Lohmann, Deviance and Conformity , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Carol A Jenkins, Developing a Photographic Essay - Making a Public Statement About a Social Problem or Issue , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: Teaching High School Sociology

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 > >>

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this resource.

All ASA members get a subscription to TRAILS as a benefit of membership. Log in with your ASA account by clicking the button below.

By logging in, you agree to abide by the TRAILS user agreement .

Our website uses cookies to improve your browsing experience, to increase the speed and security for the site, to provide analytics about our site and visitors, and for marketing. By proceeding to the site, you are expressing your consent to the use of cookies. To find out more about how we use cookies, see our Privacy Policy .

SOC 210: Introduction to Sociology

Global road warrior.

Definitions

Search for articles, search the internet.

Search Options | Summon Help

Search Tips and Examples

- attitudes AND breastfeeding AND Mexico

- public perception AND breastfeeding AND Mexico

When searching, try synonyms, which are words or phrases that are similar in meaning. To search for multiple synonyms at once, put them inside parentheses and connect them with the word OR.

- (Mexico OR Hispanic OR Latin-American)

- ("social norms" OR "societal norms" OR "cultural norms")

To focus the search a little more, just add the word AND along with a keyword:

- (Mexico OR Hispanic OR Latin-American) AND breastfeeding

- ("social norms" OR "societal norms" OR "cultural norms") AND breastfeeding

- ("social norms" OR "societal norms" OR "cultural norms") AND breastfeeding AND Mexico

You can use the same search techniques that you use to search library databases when searching Google or other Internet search engines.

Connect synonyms with the word OR and place them in parentheses.

- ("norm violations" OR "social norm") AND drinking AND Europe

- ("social norms" OR "norm violations" OR attitudes) AND "medical marijuana"

- Search Google

- Search DuckDuckGo

- << Previous: Websites

- Next: Citations >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/introductiontosociology

Examples Of Social Norms & Societal Standards: Including Cultural Norms

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Norms are implicit (unwritten) social rules which define what is expected of individuals in certain situations. They are measures of what is seen as normal in society, and govern the acceptable behavior in society (societal standards).

Norms operate at several levels, from regulations concerning etiquette at the table to moral norms relating to the prior discharging of duties ( see values ).

Social norms vary from culture to culture, and can be specific to a particular group or situation. Some social norms are explicit, such as laws or religious teachings, while others are more implicit, such as etiquette.

Violating social norms can result in negative consequences, such as being ostracized from a community or, though only in exceptional circumstances, punished by law (Bicchieri, 2011).

Everyday social convention Norms

The following are some common social norms that people in the US and UK follow daily (Hechter & Opp, 2001):

Shaking hands when greeting someone

- Saying “please” and “thank you”

Apologizing when one makes a mistake

Standing up when someone enters the room

Making eye contact during a conversation

Listening when someone is speaking

Offering help when someone is struggling

Respecting personal space

Accepting others” opinions even if we don’t agree with them

Being on time

Dressing appropriately for the occasion-

Thanking someone for a gift

Paying attention to personal hygiene

Speaking quietly in public and formal places

Clearing one”s dishes from the table after a meal at one’s own home, or at one of a friend or stranger

Not interrupting when someone else is speaking

Asking before borrowing something that belongs to someone else

Walking on the right side of a hallway or sidewalk

Saying “bless you” or “gesundheit” after someone sneezes

-Standing in line and not cutting in front of others

Yielding to pedestrians when driving

Hanging up one’s coat when entering someone else’s home

Taking off one”s shoes when entering someone else”s home (if this is the custom)

Not talking with food in one’s mouth

Chewing with one’s mouth closed

Not staring at others

Cultural Norms

Social norms vary widely across cultures and contexts (Reno et al., 1993).

For example, in Japan, some social norms that are typically followed include:

- Bowing instead of shaking hands when greeting someone

- Removing shoes before entering a home or certain public places

- Eating quietly and with small bites

- Using chopsticks correctly

- Not blowing your nose in public

- Speaking softly

- Not making direct eye contact with others

- Some social norms that are specific to meeting new people include:

- Dressing neatly and conservatively

- Exchanging business cards formally

- Presenting and receiving gifts with two hands

In South America, in contrast, people are expected to (Young, 2007):

- Greet others with a hug and a kiss on the cheek, even if one does not know them well

- Stand close to someone when talking to them

- Talk loudly for emphasis

- Make eye contact

- Use a lot of gestures when talking

- Dress more casually than in Japan or the UK

- It is common for men to whistle at women they find attractive

- In some cultures, it is considered rude to refuse a drink when offered one by someone else

- It is also considered rude to turn down food when offered some

- Table manners are not as formal as in Japan or the UK, and it is common to see people eating with their hands

- Burping and belching are also considered normal and not rude

- In some cultures, it is considered good luck to spit on someone or something

- Yawning is also considered normal and not rude

Social Norms For Students

School teaches children respect for authority, structure, and tolerance. The social norms expected of students follow suit (Hechter & Opp, 2001):

Being respectful to teachers

Listening in class

Handing in homework on time

Not talking when others are talking

Taking turns

Include everyone in activities

Playing fairly

Encouraging others

Trying one”s best

Respecting property and equipment

Being a good listener

Accepting differences among people

- Avoiding put-downs and hurtful teasing

Some social norms that are generally followed while taking exams include:

- Not cheating

- Arriving on time

- Not talking during the exam

- Listening to and following the instructions given by the person administering the exam

- Not leaving the room until the exam is over

- Not bringing in any outside materials that are not allowed

- Not looking at other people”s papers

Gender Social Norms

Some social norms that are associated with being a woman include (Moi, 2001):

- Wearing makeup

- Dressing in feminine clothing

- Being polite and well mannered

- Keeping one’s legs and arms covered

- Not swearing

- Avoiding physical labor

- Letting men take the lead

Some social norms that are associated with being a man include (Moi, 2001):

- Wearing masculine clothing

- Having short hair

- Taking up space

- Talking loudly

- Being assertive and confident

- Engaging in physical labor

- Protecting and providing for others

- leading and being in charge

Some social norms that are associated with being transgender or gender non-conforming include:

- Dressing in a way that does not conform to traditional gender norms

- Using pronouns that do not correspond to the sex assigned at birth

- Going by a different name than the one given at birth

- Requesting that others use the pronoun corresponding to their preferred gender

- Taking hormones or undergoing surgery to transition to the desired gender

Social Norms With Family

Young (2007) outlined numerous social norms pertaining to family, such as:

- Listening to elders

- Treating siblings and cousins with love and respect

- Doing chores without being asked

- Children not talking back to parents

- Paying attention during family gatherings

- Showing affection in appropriate ways

- Respecting others’ privacy

- Keeping family secrets

- Being grateful for what you have

- Appreciating the sacrifices made by your parents or guardians

- Celebrating birthdays and other special occasions together

- Sharing in family traditions

Social Norms At Work

Social norms at work are similar to those enforced at school (Hechter & Opp, 2001):

Coming to work on time

Dressing appropriately for the job

Putting in a full day”s work

Not calling in sick unnecessarily

Not taking extended lunches or coffee breaks

Not spending excessive time chatting with co-workers – Completing assigned tasks

Following company policies and procedures

Being a team player

Respecting others” opinions

Listening to and considering others” suggestions

Being an active participant in meetings

Completing assigned tasks on time

Respecting the decisions of the group even if you don’t agree with them

Social Norms While Dining Out

Some social norms that are typically followed while dining out include (Hechter & Opp, 2001):

- Dressing neatly and appropriately for the occasion

- Arriving on time for reservations

- Refraining from talking loudly

- Putting phones away and not using them at the table

- Not ordering food that is too smelly

- Ordering an appropriate amount of food

- Not leaving a mess behind

- Tipping the server generously (in American cultures)

- Saying “please” and “thank you” to the staff

- In many cultures, it is also considered rude to:

- Critique the food or drink

- Send food back

- Make a scene

- Interrupt others while they are talking

- Leave without saying goodbye

Using Your Phon e

Social norms surrounding using phones include (Carter et al., 2014):

- Putting one’s phone away when one is with other people

- In many formal situations, only using one’s phone in designated areas

- Silencing one’s phone when in class, at a meeting, or in any other situation where it would be disruptive to have one’s phone make noise

- Asking permission before using someone else’s phone

- Returning a missed call or voicemail within a reasonable amount of time

- Not texting or talking on the phone while walking if it means one’s not paying attention to where they are going and could bump into someone or something

Social Norms While Driving

Although often broken, there are expectations surrounding one”s behavior on the road (Carter et al., 2014), such as:

- Obeying the speed limit

- Yielding to pedestrians

- Coming to a complete stop at stop signs and red lights

- Using turn signals when changing lanes or making turns

- Yielding to other drivers who have the right of way

- Not driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol

- Not using a cell phone while driving

- Paying attention to the road and not being distracted by passengers, music, or other things going on inside or outside of the car

Social Norms When Meeting A New Person

In general, some social norms that are typically followed when interacting with others include (Hechter & Opp, 2001):

- Making eye contact

- Standing up straight

- Offering a handshake

- Introducing oneself

- Speaking clearly

- Listening attentively

- Asking questions

- Not interrupting others while they are talking

- Refraining from talking too much about oneself

- Being polite and well-mannered

- Not making any offensive jokes or comments

Social Norms With Friends

In general, close confidants follow a more relaxed set of social norms than acquaintances and strangers. Nonetheless, there are still expectations as to what constitutes a friend in many Western cultures, including (Young, 2007):

- Giving each other honest feedback, though often without a harsh start-up

- Accepting each other’s differences

- forgiving each other

- celebrating each other’s successes

- comforting each other during tough times

- laughing together and in response to each other’s jokes

- sharing common interests

- spending time together

- making sacrifices for each other

What is the difference between mores, norms, and values?

Mores are the regulator of social life, while norms are the very specific rules and expectations that govern the behavior of individuals in a community. Mores are a subset of norms, representing the morality and character of a group or community.

Generally, they are considered to be absolutely right. On the other hand, norms can involve customs and expected behaviors that are more flexible and can change over time.

They usually deal with day-to-day behavior and are not as deeply ingrained as mores. While the violation of a norm may be uncomfortable, the violation of a more is usually socially unacceptable.

Mores are beliefs that we have about what is important, both to us and to society as a whole. A value, therefore, is a belief (right or wrong) about the way something should be.

While norms are specific rules dictating how people should act in a particular situation, values are general ideas that support the norm”.

In short, the values we hold are general behavioral guidelines. They tell us what we believe is right or wrong, for example, but that does not tell us how we should behave appropriately in any given social situation. This is the part played by norms in the overall structure of our social behavior.

Berkowitz, A. D. (2005). An overview of the social norms approach. Changing the culture of college drinking: A socially situated health communication campaign, 1, 193-214.

Bicchieri, C. (2011). Social Norms . Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Carter, P. M., Bingham, C. R., Zakrajsek, J. S., Shope, J. T., & Sayer, T. B. (2014). Social norms and risk perception: Predictors of distracted driving behavior among novice adolescent drivers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54 (5), S32-S41.

Chung, A., & Rimal, R. N. (2016). Social norms : A review. Review of Communication Research, 4, 1-28.

Hechter, M., & Opp, K. D. (Eds.). (2001). Social norms .

Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms . Communication theory, 15 (2), 127-147.

Moi, T. (2001). What is a woman?: and other essays. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Reno, R. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kallgren, C. A. (1993). The transsituational influence of social norms. Journal of Personality and social psychology, 64 (1), 104.

Sunstein, C. R. (1996). Social norms and social roles . Colum. L. Rev., 96, 903.

Young, H. P. (2007). Social Norms .

102 Examples of Social Norms (List)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

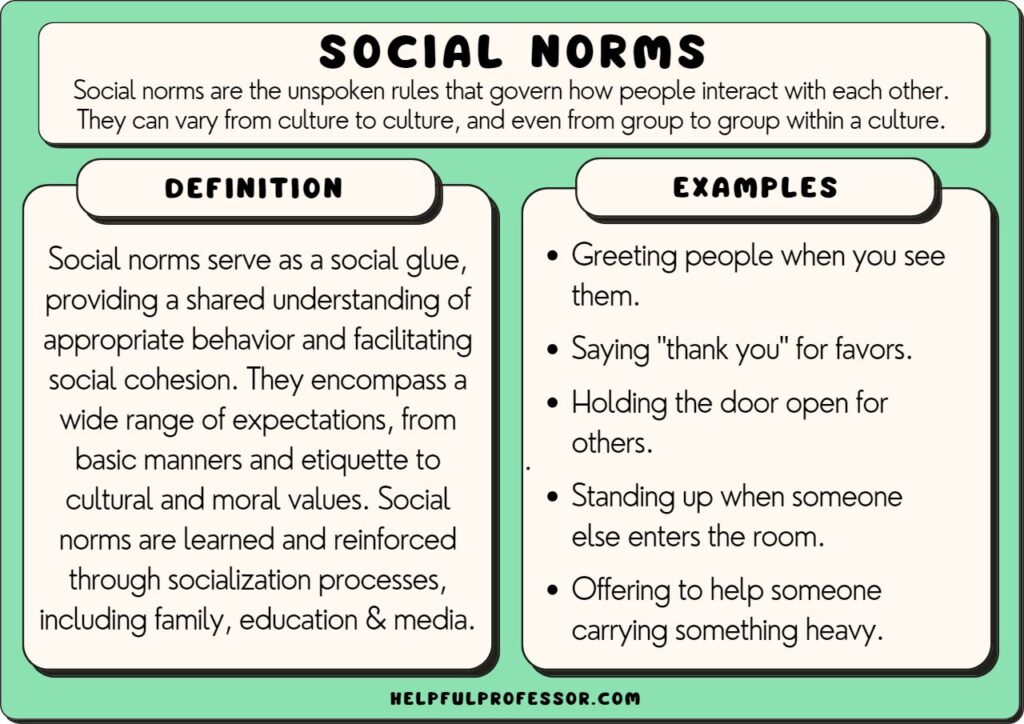

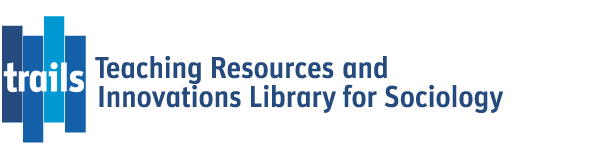

Social norms are the unspoken rules that govern how people interact with each other. They can vary from culture to culture, and even from group to group within a culture.

Some social norms are so ingrained in our psyches that we don’t even think about them; we just automatically do what is expected of us. Social norms examples include covering your mouth when you cough, waiting your turn, and speaking softly in a library.

Breaking societal norms can sometimes lead to awkward or uncomfortable situations. For example, if you’re in a library where it’s considered rude to talk on your cell phone, and you answer a call, you’ll likely get some disapproving looks from the people around you.

Understanding the social norms of the place you’re visiting is an important part of cultural etiquette to show respect for the people around you.

Examples of Social Norms

- Greeting people when you see them.

- Saying “thank you” for favors.

- Holding the door open for others.

- Standing up when someone else enters the room.

- Offering to help someone carrying something heavy.

- Speaking quietly in public places.

- Waiting in line politely.

- Respecting other people’s personal space.

- Disposing of trash properly.

- Refraining from eating smelly foods in public.

- Paying for goods or services with a smile.

- Complimenting others on their appearance or achievements.

- Asking others about their day or interests.

- Avoiding gossip and rumors.

- Volunteering to help others in need.

- Saying “I’m sorry” when you’ve made a mistake.

- Supporting others in their time of need.

- Participating in group activities.

- Respecting authority figures.

- Being on time for important engagements.

- Avoiding interrupting others when they are speaking.

- Showing interest in other people’s lives and experiences.

- Refraining from using offensive language or gestures.

- Being honest and truthful with others at all times.

- Treating others with kindness and respect, regardless of their social status or background.

- Putting the needs of others before your own.

- Participating in charitable works and activities.

- Helping others whenever possible.

- Welcoming guests into your home or place of business.

- Nodding, smiling, and looking people in the eyes to show you are listening to them.

- Following the laws and regulations of your country.

- Respecting the rights and beliefs of others.

- Cooperating with others in order to achieve common goals.

- Being tolerant and understanding of different viewpoints.

- Displaying good manners and etiquette in social interactions.

- Waiting in line for your turn.

- Taking your shoes off before walking into someone’s house.

- Putting your dog on a leash in parks and other public spaces.

- Letting the elderly or pregnant people take your seat on a bus.

Social Norms for Students

- Arrive to class on time and prepared.

- Pay attention and take notes.

- Stay quiet when other students are working.

- Raise your hand if you have a question.

- Do your homework and turn it in on time.

- Participate in class discussions.

- Respect your teachers and classmates.

- Follow the school’s rules and regulations.

- Use appropriate language and behavior.

- Ask permission to be excused if you need to go to the bathroom.

- Go to the bathroom before class begins.

- Keep your workspace clean.

- Do not plagiarize or cheat.

- Wait your turn to speak.

- Ask permission to use other people’s supplies.

- Include all your peers in your group when doing group work.

Related: Classroom Rules for Middle School

Social Norms while Dining Out

- Wait to be seated.

- Remain seated until everyone is served.

- Don’t reach across the table.

- Use your napkin.

- Don’t chew with your mouth open.

- Don’t talk with your mouth full.

- Keep elbows off the table.

- Use a fork and knife when eating.

- Drink from a glass, not from the bottle or carton.

- Request more bread or butter only if you’re going to eat it all.

- Don’t criticize the food or service.

- Thank your server when you’re finished.

- Leave a tip if you’re satisfied with the service.

Social Norms while using your Phone

- Keep your phone on silent or vibrate mode while in meetings.

- Don’t answer your phone in a public place unless it’s an emergency.

- Don’t talk on the phone while driving.

- Don’t text while driving.

- Don’t take or make calls during class.

- Don’t use your phone in a movie theater.

- Turn off your phone when you’re with someone else.

- Place your phone on airplane mode while flying.

- Do not look at someone else’s phone.

- Ensure your ringtone is inoffensive when in public or around children.

Social Norms in Libraries

- Be quiet and respect the other patrons.

- Don’t talk on your phone.

- Don’t bring food or drinks into the library.

- Don’t sleep in the library.

- Don’t bring pets into the library.

- Return all books to the correct location.

- Don’t mark or damage library books.

- Make sure your cell phone is turned off.

- Return your books on time.

Social Norms in Other Countries

- In France, it is considered polite to kiss acquaintances on both cheeks when meeting them.

- In Japan, it is customary to take your shoes off when entering someone’s home.

- In India, it is considered rude to show the soles of your feet or to point your feet at someone else.

- In Italy, it is common for people to give each other a light kiss on the cheek as a gesture of hello or goodbye.

- In China, it is customary to leave some food on your plate after eating, as a sign of respect for the cook.

- In Spain, it is customary to call elders “Don” or “Doña.”

- In Iceland, it is considered polite to say “thank you” (Takk) after every meal.

- In Thailand, it is customary to remove your shoes before entering a home or temple.

- In Germany, it is customary to shake hands with everyone you meet, both men and women.

- In Argentina, it is customary for people to hug and kiss cheeks as a gesture of hello or goodbye.

Social Norms that Should be Broken

- “ Women should be polite” – Stand up for what you believe in, even if it makes you look bossy.

- “Don’t draw attention to yourself” – Embrace your uniqueness and difference so long as you’re respectful of others.

- “Don’t question your parents or your boss” – Protest bad behavior from people in authority if you know you’re morally right.

- “Mistakes are embarrassing” – It’s okay to make mistakes and be seen to fail. It means you’re making an effort and pushing your boundaries.

- “Respect your elders” – If your elders are engaging in bad behavior, stand up to them and let them know you’re taking note of what they’re doing.

Cultural vs Social Norms

Cultural norms are the customs and traditions that are passed down from one generation to the next. They’re connected to the traditions, values, and practices of a particular culture.

Societal norms, on the other hand, reflect the current social standard for appropriate behavior within a society. In modern multicultural societies, there are different groups with different cultural norms, but they must all agree on a common set of social norms for public spaces.

We also have a concept called group norms , which define how smaller groups – like workplace teams or sports teams – will operate. These might differ from group to group, and are highly dependant on the expectations and standards of the group/team leader.

Norms Change Depending on the Context

Norms are different depending on different contexts, including in different eras, and in different societies. What might be considered polite in one context could be considered rude in another.

For example, norms in the 1950s were much more gendered. Negative gender stereotypes restricted women because it was normative for women to be quiet, polite, and submissive in public. Today, women have much more equality.

Similarly, the norms and taboos in the United States will be very different from those in China. For example, Chinese businessmen are often expected to share expensive gifts during negotiations. In the United States, this could be considered bordering on bribery.

What are the Four Types of Norms?

There are four types of norms : folkways, mores, taboos, and laws.

- Folkways are social conventions that are not strictly enforced, but are generally considered to be polite or appropriate. An example of a folkway is covering your mouth when you sneeze.

- Mores are social conventions that are considered to have a moral dimension. Due to their moral dimension, they’re generally considered to be more important than folkways. Violation of mores can result in social sanctions so they often overlap with laws (mentioned below). An example of a more is not drinking and driving.

- Taboos are considered ‘negative norms’, or things that you should avoid doing. If you do them, you’ll be seen as rude. An example of a taboo is using your phone in a movie theater or spitting indoors.

- Laws are the most formal and serious type of norm. They are usually enforced by the government and can result in criminal penalties if violated. Examples of laws include not stealing from others and not assaulting others.

Conclusion: What are Social Norms?

Social norms are defined as the unspoken rules that help us to get along with others in a polite and respectful manner. It’s important to follow them so that we can maintain a positive social environment for everyone involved. Social norms examples include not spitting indoors, covering your mouth when you sneeze, and shaking hands with everyone you meet.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How norm violators rise and fall in the eyes of others: The role of sanctions

Florian Wanders

1 Work and Organizational Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Astrid C. Homan

Annelies e. m. van vianen, rima-maria rahal.

2 Social Psychology, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands

Gerben A. van Kleef

3 Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Associated Data

Data and analysis code are available through https://osf.io/xjpe5/ .

Norm violators demonstrate that they can behave as they wish, which makes them appear powerful. Potentially, this is the beginning of a self-reinforcing loop, in which greater perceived power invites further norm violations. Here we investigate the possibility that sanctions can break this loop by reducing the power that observers attribute to norm violators. Despite an abundance of research on the effects of sanctions as deterrents for norm-violating behavior, little is known about how sanctions may change perceptions of individuals who do (or do not) violate norms. Replicating previous research, we found in two studies ( N 1 = 203, N 2 = 132) that norm violators are perceived as having greater volitional capacity compared to norm abiders. Qualifying previous research, however, we demonstrate that perceptions of volition only translate into attributions of greater power in the absence of sanctions. We discuss implications for social hierarchies and point out avenues for further research on the social dynamics of power.

Introduction

Social norms—implicit or explicit rules or principles that are understood by members of a group and that guide and/or constrain behavior [ 1 ]–create a shared understanding of what is acceptable within a given context and thereby contribute to the functioning of social collectives [ 2 – 4 ]. Accordingly, research has documented that people who violate norms tend to elicit negative responses in others, including unfavorable social perceptions [ 5 ], negative emotions [ 6 – 8 ], scolding [ 9 ], gossip [ 10 ], and punishment [ 11 – 13 ]. Intriguingly, however, research has also demonstrated that norm violators are perceived as powerful [ 5 ], high in status [ 14 ], and influential [ 15 ]. This possibly opens the door to a “self-reinforcing loop” (p. 351 [ 16 ]): Norm violators appear powerful and bystanders may submit to powerful others [ 17 ], thereby inviting further norm violations and consolidating norm violators’ power [ 5 ]. The question then arises: How can we prevent people from gaining unjustified influence through norm violations? Here we investigate whether sanctions reduce the extent to which norm violators appear powerful, thereby breaking the self-reinforcing loop to power that norm violations can set off.

Norm violations signal power

We define norm violations as any behavior that infringes on a norm [ 5 ], whether informal (i.e., learned by observing others) or formal (i.e., written). Norm violations are ubiquitous, from talking at the movies to using public transport without a ticket. These behaviors violate social norms that are both endorsed and enacted by most members of a group (injunctive and descriptive norms, respectively) [ 4 ]. Injunctive and descriptive norms are individually perceived but when people are cognizant of prevailing norms and endorse these norms, both types of norms can converge and be shared at the collective level [ 18 ]. By ignoring the norms that bind others, norm violators demonstrate that they can act as they wish and do not fear interference from others [ 5 ]. This is a freedom that typically comes with higher rank [ 19 ].

The influential approach/inhibition theory of power [ 20 ] states that power, which is commonly defined as asymmetrical control over valuable resources that enables influence, liberates behavior, whereas powerlessness constrains it. Indeed, ample research supports that power renders people more likely to act, even if the resulting behavior is inappropriate or harmful [ 21 , 22 ]. Because behavioral freedom is thus intimately associated with power, people who observe unchecked behavior of others may make inferences about others’ level of power. Indeed, people who act as they wish and disregard social norms are perceived as having high status [ 14 ], influence [ 15 ], and power [ 5 ]. Furthermore, these perceptions can, under particular circumstances, fuel actual granting of power, for instance via the conferral of control over outcomes, voting, and leadership endorsement [ 23 , 24 ].

In line with the notion that power liberates behavior, previous research has demonstrated that norm violators are perceived as powerful because they appear to experience the freedom to act as they please [ 5 , 14 , 15 ]–that is, they are high on volitional capacity. In other words, norm violators are perceived as powerful because their behavior signals an underlying quality, namely the freedom to act at will. This argument resonates with costly signaling theory [ 25 , 26 ], which states that any seemingly costly behavior (involving large investments or risks of receiving negative outcomes) functions as a signal of an underlying characteristic [ 25 , 26 ]. An example of costly behavior is the reckless driving of young men as to show their strength and skills to peers and potential mates, risking serious injury or death—a type of behavior that is under particular circumstances “rewarded” with power [ 27 ]. Norm violations are potentially costly as they are frequently sanctioned [ 14 ] by means of formal (e.g., legal) punishment [ 28 ] and/or informal (social) punishment (e.g., anger, social exclusion [ 29 , 30 ]). According to costly signaling theory, people who engage in potentially costly norm-violating behavior signal that they possess traits that allow them not to worry about interferences from others. Because this capacity to do what one wants is typically reserved for the powerful [ 31 ], norm violators appear powerful when there are no additional cues that provide direct information about this attribute [ 5 ].

Sanctions curb norm violators’ perceived power

If norm violations signal power, this opens the door to a self-reinforcing loop [ 5 , 16 ]. Norm violators’ claim to power is likely to be granted because people tend to submit to powerful others [ 17 , 24 , 32 ]. For example, people who interrupt others during meetings may be granted influence by receiving more time to speak [ 14 , 33 ]. As a consequence, their contributions may be noted more readily, which increases their chances for influence and promotion [ 34 ]. Norm violators may therefore climb up in social hierarchies. The question then arises: Can people be prevented from gaining power through norm violations?

Here we adopt a social-perceptual lens and investigate whether sanctions reduce the extent to which norm violators appear powerful. Specifically, we propose that sanctions reduce the signal of power that norm violators’ apparent volitional capacity sends. Bystanders easily infer that norm violators are free to act according to their own volition [ 5 ]. In the absence of additional information, this inference of volitional capacity functions as a signal of power [ 5 , 16 ]. However, we argue that if bystanders receive information that norm violators are sanctioned, they no longer need to rely on such signals. That is, they may directly conclude that norm violators who are reprimanded for their behavior do not have the power they seemed to have but are bound by the same norms that bind others around them. To summarize, we argue that bystanders perceive norm violators as powerful because they infer that norm violators have the capacity to act according to their own volition (replication of Van Kleef et al [ 5 ]). However, we propose that sanctions reduce the extent to which observers perceive norm violators as powerful by severing the link between volition and power perceptions (see Fig 1 ).

The goal of the current manuscript was to investigate whether sanctions reduce the extent to which norm violators are seen as powerful. In our experimental design we focus on the violation of a legal norm that most people in society tend to endorse and enact, and sanctions refer to formal rather than informal sanctions. We present the results of two studies which replicate the finding that unsanctioned norm violators appear powerful [ 5 ], and support the current hypothesis that sanctions curb the effect of norm violations on power perceptions. The investigation of the exact mechanism underlying this effect was in part exploratory, and we denote where this was the case when presenting our results.

Participants and design

Study 1 employed a 2 (norm violation: abide vs. violate) × 2 (sanctioning: no sanction vs. sanction) between-subjects design, and participants could win one of four 15€ vouchers. This study was part of a student project using a cell size of about 50 participants and including an additional exploratory condition ( n = 121) which we do not report here (see S1 File for further information). Ethics approval was obtained from the ethical review board, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands (ref.: 2014-WOP-3498). The code of conduct of the German Society for Psychology does not require special permits for international researchers and, for ethical considerations in research, the same codified ethical guidelines apply in Germany as in the Netherlands. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation (online, by clicking “yes”).

We recruited 236 participants at a German university campus and through social media, of which 203 were retained for analyses (153 women, 50 men, M age = 23.78, range = 18–59). Seventeen participants were removed because they did not complete the questionnaire, and 16 participants were excluded because they failed attention checks. These exclusion criteria were decided a-priori. A sensitivity analysis conducted in G-power suggested that when testing a moderated mediation model involving 5 predictors (norm violation, volition, sanctioning, norm violation x sanctioning, volition x sanctioning) and α = 0.05 the analysis would have a power of 0.80 to detect a small to medium effect (ƒ 2 = 0.06). In addition, we calculated ν-statistics [ 35 ] for the central tests of our moderated mediation model. The ν-statistic for the regressions of volition on norm violation was ν = 0.897. The ν-statistic for the regression of power on volition, norm violation, sanctioning, and the two-way interactions between violation and sanctioning as well as volition and sanctioning was ν = 1.000. These statistics show that this study was sufficiently powered.

Manipulation

Participants read about a traveler who either purchased a ticket before boarding a train (norm abider) or purchased a snack instead and did not purchase a ticket (norm violator). The norm abider could not find the ticket when approached by a controller on the train but told the controller that he did buy one. Likewise, the norm violator told the controller that he did buy a ticket but said that he had already been checked. The controller then either did not insist on seeing the ticket (no sanction) or did insist and fined the traveler who was unable to show the ticket (sanction; see the S1 File for the full scenarios). Assignment to conditions was random.

After reading about the traveler, participants indicated to what extent they thought the traveler acted out of his own volition, and to what extent they perceived the traveler as powerful. The measures including all items can be found in the supplementary material. Participants answered a set of additional questions (administered as part of a thesis project) before completing manipulation and attention checks.

Volition perceptions . Perceptions of volition (α = .88) were measured with six items [ 1 ]. An example item is: “To what extent does this person feel free to do what s/he wants?” with scales ranging from 1 = not very much , to 7 = very much .

Power perceptions . Perceptions of power (α = .88) were measured with a validated 8-item sense of power scale [ 36 ]. Example items are: “I think this person has a great deal of power” and “I think this person’s wishes do not carry much weight (reverse scored)” with scale anchors ranging from 1 = strongly disagree , to 7 = strongly agree .

Manipulation checks . Two questions each assessed in how far participants thought the traveler violated norms (“To what extent did the traveler violate norms?”; “To what extent did the traveler abide by norms?” [reverse-scored]; r = .87) and in how far participants thought the traveler was sanctioned (“To what extent was the traveler sanctioned?”; “To what extent did the traveler get away unsanctioned?” [reverse-scored]; r = .93). Scale anchors for both manipulation checks were 1 = not at all , and 7 = extremely .

Attention checks . Participants answered two questions each asking whether traveling without a ticket was allowed/prohibited, whether the traveler did/did not buy a ticket, whether the traveler was/was not fined, and whether the traveler was/was not honest. Answer options were yes versus no, and participants who provided incorrect responses were excluded from the analyses.

Manipulation checks

To test whether the manipulations of norm violation and sanctioning were successful, we ran two separate ANOVAs with norm violation and sanctioning as between-subjects factors. First, the ANOVA with the norm violation manipulation check as dependent variable revealed the expected main effect of norm violation, F (1,199) = 1085.56, p < .001, η p 2 = .845. Norm violators ( M = 6.29, SD = 0.78, 95% CI [6.136, 6.442]) were seen as violating norms to a considerably greater extent than norm abiders ( M = 2.14, SD = 1.13, 95% CI [1.916, 2.361]). Unexpectedly, there was also a main effect of sanctioning, F (1,199) = 18.41, p < .001, η p 2 = 0.085, and a significant interaction effect, F (1,199) = 18.52, p < .001, η p 2 = 0.085. Further probing using simple slopes analysis revealed no significant effect of sanctioning for norm violators, t (199) = 0.01, p = .993, 95% CI [-0.348, 0.351], d = 0.002, but there was a significant effect for norm abiders, t (199) = 6.06, p < .001, 95% CI [0.728, 1.429], d = 1.207: Non-sanctioned norm abiders were perceived as violating norms to a greater extent than sanctioned norm abiders. Given that the effect sizes of the unexpected effects (both η p 2 = 0.085) were ten times smaller than that of the intended effect ( η p 2 = .845) we consider this manipulation successful.

Second, the ANOVA with the sanctioning manipulation check as dependent variable revealed only the expected main effect of sanctioning, F (1,199) = 1589.38, p < .001, η p 2 = .889. Sanctioned travelers ( M = 5.94, SD = 1.06, 95% CI [5.733, 6.149]) were seen as considerably more sanctioned than non-sanctioned travelers ( M = 1.29, SD = 0.51, 95% CI [1.186, 1.388]). Neither the effect of norm violation nor the interaction between sanctioning and norm violation were significant ( F < 2.85, p >.093). Thus, the manipulation was successful.

Replication of the norm violation-perceived power link

Next, we aimed to replicate Van Kleef et al.’s [ 5 ] norm violation → volition → perceived power links in the absence of sanctions, before investigating how these links are affected by the presence of sanctions. As illustrated in the left-hand panel of Fig 2 , a planned contrast revealed that in the absence of sanctions norm violators appeared more powerful than norm abiders, t (99) = 2.02, p = .047, 95% CI [0.005, 0.690], d = 0.401 (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations).

Sanction

Violation | No sanction | Sanction |

|---|

| Abide | Violate | Abide | Violate |

|---|

| Volition | 4.41 (1.01) | 6.06 (0.88) | 3.75 (1.16) | 5.77 (1.07) |

| Power | 5.27 (0.94) | 5.61 (0.79) | 3.73 (0.90) | 3.83 (0.89) |

Note. Means within a row with a different subscript differ at p < .05.

For testing our directional prediction that volition mediates the link between norm violation and perceived power, we used one-tailed tests [ 37 ]. Norm violators were seen as acting more according to their own volition compared to norm abiders, B = 1.65, SE = 0.19, t (99) = 8.76, p < .001, 95% CI [1.276, 2.023], and greater perceived volitional capacity was, in turn, related to greater perceived power, B = 0.18, SE = 0.09, t (98) = 1.99, p = .025, 95% CI [0.029, Inf]. Bootstrapped confidence intervals indicate that the indirect effect of norm violation on perceived power via volition was significant, B indirect = 0.30, SE = 0.15, 95% CI [0.010, 0.582], υ = 0.029. The effect size υ indicates a sufficient although small indirect effect [ 38 ]. We therefore consider the replication of the norm violation → volition → perceived power links successful.

The role of sanctioning

Concerning the effect of sanctioning on the norm violation → volition → perceived power link, we predicted that sanctioning would reduce the extent to which norm violators appear powerful. Furthermore, we proposed that sanctioning would reduce the signal of power that norm violators’ apparent volitional capacity sends. We tested this idea in three steps. First, we tested whether sanctioning reduced the extent to which norm violators were seen as powerful. A planned contrast suggests that sanctioned norm violators were indeed perceived as less powerful than non-sanctioned norm violators t (100) = -10.68, p < .001, 95% CI [-2.114, -1.452], d = -2.115 (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations).

Next, we explored where in the norm violation → volition → perceived power links sanctions exerted their moderating impact. Our theoretical argument suggested that observers perceive norm violators as having greater volitional capacity than norm abiders regardless of whether they are sanctioned, whereas they will perceive norm violators as powerful only if they are not sanctioned. In line with this idea, a mixed-model ANOVA among norm violators with sanctioning (no sanction vs. sanction) as between-subjects factor and scale (volition vs. power) as within-subjects factor revealed—besides significant main effects of sanctioning, F (1,100) = 51.23, p < .001, η p 2 = .339 and scale F (1,100) = 122.81, p < .001, η p 2 = .551—a significant interaction between both, F (1,100) = 47.70, p < .001, η p 2 = .323. As Fig 3 shows, whereas sanctions did not significantly affect the extent to which norm violators appeared to act according to their own volition, t (100) = -1.50, p = .136, 95% CI [-0.675, 0.093], d = -0.298, they significantly reduced perceptions of power t (100) = -10.68, p < .001, 95% CI [-2.114, -1.452], d = -2.115. This suggests that sanctions reduce the signal of power that norm violators’ apparent volitional capacity sends.

Error bars are standard errors around the mean.

In a final step, we tested whether sanctioning moderated the effect of volition on perceived power in the norm violation → volition → perceived power link. Sanctioning moderated the effect of volition on perceived power in the mediation chain when the confidence interval for the product a × b 2 of the effect of norm violation on volition (a in Fig 4 , left panel) and the interaction of volition and sanction on power perception (b 2 ) excludes zero [ 39 ]. See the supplement for a detailed explanation.

Black arrows in the statistical model highlight relevant effects for moderated mediation (ab 2 ). Simple slopes with standard errors (right) illustrate b 2 , the lack of an interaction of volition and sanctions on power perceptions.

Contrary to our expectations, this was not the case, B = 0.10, SE = 0.2, 95% CI [-0.294, 0.520]. Whereas the effect of norm violation on volition (a) was significant, B = 1.85, SE = 0.15, t (201) = 12.40, p < .001, 95% CI [1.553, 2.141], the interaction between volition and sanctioning on power (b 2 ) was not, B = 0.05, SE = 0.12, t (197) = 0.45, p = .651, 95% CI [-0.181, 0.289], rendering the product a × b 2 nonsignificant. We therefore cannot conclude that sanctioning reduced the extent to which norm violators’ apparent volitional capacity translated into power perceptions. Fig 4 (right panel) illustrates this absence of an interaction between sanctions and volition (slopes are similar across conditions) and shows that sanctioning directly reduced perceptions of power.

Study 1 replicated the finding that norm violators are seen as acting more according to their own volition than norm abiders, and that greater volition in turn related to greater inferences of power [ 5 ]. As expected, sanctioning reduced the extent to which norm violators were seen as powerful. However, sanctioning did not significantly affect the extent to which norm violators appeared to act according to their own volition. Although this is consistent with our theoretical model, which proposes that sanctioning targets the power-signaling effect of volition in the norm violation → volition → perceived power mediation chain, we found no full support for this pattern. Instead, sanctioning directly reduced perceptions of power irrespective of volition. One explanation for why sanctioning did not moderate the power-signaling effect of volition could be that volition was not strongly linked to power perceptions in this study in the first place. Therefore, we aimed to replicate the norm violation → volition → perceived power chain in a second study which also allowed us to improve the ecological validity of our design.

The 2(violate vs. abide) × 2(no sanction vs. sanction) design of Study 1 allowed us to test our predictions in a single moderated mediation model. Yet, despite its elegance, this design necessitated a compromise: To enable orthogonal manipulations of norm violation and sanctioning, neither the norm violator (who never purchased a ticket) nor the norm abider (who lost it) showed a valid ticket, which is sanctionable behavior. Although this enabled a full-factorial design allowing different comparisons between conditions, including a condition with sanctions for a norm abider who lost the ticket, may have undermined the credibility of the scenario, and renders interpretation of the results less straightforward. First, norm violators might have appeared more powerful than norm abiders not because norm violators demonstrated volitional capacity, but because norm abiders seemed incapable. Second, one might question whether norm abiders who lost their ticket really abided by norms, as, according to German train regulations, travelers must at all times be able to show a valid ticket. Therefore, in Study 2, we let the norm abider buy and show a ticket to the controller, moving from the 2×2 design of Study 1 to a 3-cell design.

Study 2 employed a 3-cell (norm abider vs. norm violator vs. sanctioned norm violator) between-subjects design and relied on a sample of Dutch participants that was collected as part of a larger project. Participants could win one of five 10€ vouchers. Ethics approval was obtained from the ethical review board, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Amsterdam (ref.: 2017-COP-8050). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation (online, by clicking “yes”).

To ensure comparable cell sizes as in Study 1, we recruited 159 participants at the university, of which 132 were retained for analyses (83 women, 49 men, M age = 25.80, range = 18–66). Seven participants were removed because they did not complete the questionnaire, and an additional 20 participants were excluded because they failed attention checks. These exclusion criteria were decided a-priori. A sensitivity analysis conducted in G-power suggested that with 5 predictors (experimental condition 1 [non-sanctioned norm violators vs. abiders], experimental condition 2 [non-sanctioned norm violators vs. sanctioned norm violators], volition, violation x condition 1, volition x condition 2) and α = 0.05 the analysis would have a power of 0.80 to detect a small to medium effect (ƒ 2 = 0.10). In addition, we calculated ν-statistics [ 35 ] to establish sufficient power. The central test in Study 2 constituted the regression of power on the interaction between volition and experimental condition, which resulted in a ν-statistic of ν = .999 (regressing of volition on experimental condition resulted in a ν-statistic of 0.955). This indicates that our study was sufficiently powered.

As in Study 1, participants read about a traveler who either purchased a ticket before boarding a train (norm abider) or purchased a snack instead (and no ticket). When approached by a controller, the norm abider showed the ticket. The norm violator told the controller that he did buy a ticket but said that he had already been checked. The controller then either did not insist on seeing the ticket (norm violator) or did insist and fined the traveler who was unable to show the ticket (sanctioned norm violator; see the S1 File for the full scenarios). Assignment to conditions was random.

After reading about the traveler, participants completed the same measures of perceived power (α = .87) and volition (α = .85) as in Study 1. Besides completing manipulation and attention checks (see below), participants answered a set of additional questions as part of a student project, which were not analyzed (see the S1 File ).

Manipulation checks . Three questions assessed in how far participants thought the norm violator violated norms: “He behaved in line with norms”, “He violated norms”, and “He behaved appropriately” (reverse coded, α = .92; adapted from Stamkou et al [ 23 ]). Three further questions assessed in how far participants thought the traveler was sanctioned: “The traveler was punished”, “The traveler had to pay for his behavior”, and “The traveler was fined” (α = .96). Scale anchors for all scales in this study ranged from 1 = completely disagree , to 7 = completely agree .

Attention check . Participants were asked whether the traveler bought a ticket and whether the controller fined the traveler. Answer options were yes versus no, and participants who provided incorrect responses were excluded from the analyses.

Separate ANOVAs on the manipulation checks with experimental condition as between subjects variable revealed significant differences between conditions on both the norm violation manipulation check, F (2,129) = 161.62, p < .001, η p 2 = .715, and the sanctioning manipulation check, F (2,129) = 179.08, p < .001, η p 2 = .735. Participants perceived both the sanctioned ( M = 5.89, SD = 0.87, 95% CI [5.630, 6.143]) and the non-sanctioned norm violator ( M = 5.91, SD = 1.03, 95% CI [5.585, 6.237]) to have violated norms to a greater extent than the norm abider ( M = 2.41, SD = 1.23, 95% CI [2.036, 2.782]). Participants also perceived the sanctioned norm violator ( M = 5.95, SD = 0.85, 95% CI [5.702, 6.199]) as having been sanctioned to a greater extent than either the non-sanctioned norm violator ( M = 2.28, SD = 1.13, 95% CI [1.927, 2.643]), or the norm abider ( M = 2.20, SD = 1.24, 95% CI [1.821, 2.573]). This shows that the manipulations were successful.

As in Study 1, we aimed to replicate Van Kleef et al.’s [ 5 ] norm violation → volition → perceived power links in the absence of sanctioning, before investigating how these links are affected by sanctioning. As illustrated in Fig 5 , a planned contrast revealed that, in the absence of sanctions, norm violators appeared more powerful than norm abiders, t (83) = 7.27, p < .001, 95% CI [0.697, 1.222], d = 1.579 (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations).

| Condition | Control | No sanction | Sanction |

|---|

| Volition | 4.21 (0.68) | 5.33 (0.73) | 5.13 (0.83) |

| Power | 4.07 (0.49) | 5.03 (0.71) | 3.81 (0.82) |

Note . Means within a row with a different subscript differ at p < .05.

Concerning the mediating role of volition, norm violators were seen as acting more according to their own volition compared to norm abiders, B = 1.12, SE = 0.15, t (83) = 7.30, p < .001, 95% CI [0.816, 1.427], and greater volitional capacity was, in turn, related to greater perceived power, B = 0.29, SE = 0.09, t (82) = 3.30, p = .001, 95% CI [0.117, 0.471. Bootstrapped confidence intervals showed that the indirect effect of norm violation on perceived power via volition was significant, B indirect = 0.33, SE = 0.12, 95% CI [0.118, 0.623], υ = 0.046. We therefore consider the replication of the norm violation → volition → perceived power chain successful and proceed to investigate how sanctions affect this chain.

We predicted that sanctioning reduces the extent to which norm violators appear powerful. Furthermore, we proposed that sanctioning reduces the signal of power that norm violators’ apparent volitional capacity sends. First, we tested whether sanctioning reduces the extent to which norm violators are seen as powerful. A planned contrast indicates that sanctioned norm violators were indeed perceived as less powerful than non-sanctioned norm violators, t (86) = -7.38, p < .001, 95% CI [-1.544, -0.889], d = -1.578 (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations).