- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

What is racism?

What are some of the societal aspects of racism, what are some of the measures taken to combat racism.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Social Sciences LibreTexts - Racism

- Academia - Racial Discrimination and Redlining in Cities

- GlobalSecurity.org - Racism

- PBS LearningMedia - American Experience - A Class Apart: The Birth and Growth of Racism Against Mexican-Americans

- Frontiers - Racism and censorship in the editorial and peer review process

- United Nations - The Ideology of Racism: Misusing science to justify racial discrimination

- National Endowment for the Humanities - Humanities - El Movimiento

- PBS - Frontline - A Class Divided - Documentary Introduction

- Cornell Law School - Legal Information Institute - Racism

- racism - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- racism - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

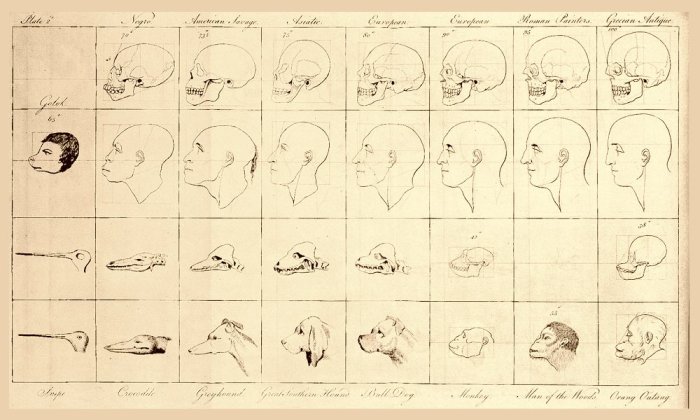

Racism is the belief that humans can be divided into separate and exclusive biological entities called “races”; that there is a causal link between inherited physical traits and traits of personality, intellect, morality, and other cultural and behavioral features; and that some races are innately superior to others. Racism was at the heart of North American slavery and the colonization and empire-building activities of western Europeans, especially in the 18th century. Since the late 20th century the notion of biological race has been recognized as a cultural invention, entirely without scientific basis. Most human societies have concluded that racism is wrong, and social trends have moved away from racism.

Historically, the practice of racism held that members of low-status “races” should be limited to low-status jobs or enslavement and be excluded from access to political power, economic resources, and unrestricted civil rights. The lived experience of racism for members of low-status races includes acts of physical violence, daily insults, and frequent acts and verbal expressions of contempt and disrespect.

Racism elicits hatred and distrust and precludes any attempt to understand its victims. Many societies attempt to combat racism by raising awareness of racist beliefs and practices and by promoting human understanding in public policies. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights , adopted by the United Nations in 1948, is an example of one measure taken to combat racism. In the United States, the civil rights movement ’s fight against racism gained national prominence during the 1950s and has had lasting positive effects.

Recent News

racism , the belief that humans may be divided into separate and exclusive biological entities called “races”; that there is a causal link between inherited physical traits and traits of personality, intellect, morality , and other cultural and behavioral features; and that some races are innately superior to others. The term is also applied to political, economic, or legal institutions and systems that engage in or perpetuate discrimination on the basis of race or otherwise reinforce racial inequalities in wealth and income, education , health care, civil rights, and other areas. Such institutional, structural, or systemic racism became a particular focus of scholarly investigation in the 1980s with the emergence of critical race theory , an offshoot of the critical legal studies movement. Since the late 20th century the notion of biological race has been recognized as a cultural invention, entirely without scientific basis.

Following Germany’s defeat in World War I , that country’s deeply ingrained anti-Semitism was successfully exploited by the Nazi Party , which seized power in 1933 and implemented policies of systematic discrimination, persecution, and eventual mass murder of Jews in Germany and in the territories occupied by the country during World War II ( see Holocaust ).

In North America and apartheid -era South Africa , racism dictated that different races (chiefly blacks and whites) should be segregated from one another; that they should have their own distinct communities and develop their own institutions such as churches, schools, and hospitals; and that it was unnatural for members of different races to marry .

Historically, those who openly professed or practiced racism held that members of low-status races should be limited to low-status jobs and that members of the dominant race should have exclusive access to political power, economic resources, high-status jobs, and unrestricted civil rights . The lived experience of racism for members of low-status races includes acts of physical violence , daily insults, and frequent acts and verbal expressions of contempt and disrespect, all of which have profound effects on self-esteem and social relationships.

Racism was at the heart of North American slavery and the colonization and empire-building activities of western Europeans, especially in the 18th century. The idea of race was invented to magnify the differences between people of European origin and those of African descent whose ancestors had been involuntarily enslaved and transported to the Americas. By characterizing Africans and their African American descendants as lesser human beings, the proponents of slavery attempted to justify and maintain the system of exploitation while portraying the United States as a bastion and champion of human freedom, with human rights , democratic institutions, unlimited opportunities, and equality. The contradiction between slavery and the ideology of human equality, accompanying a philosophy of human freedom and dignity, seemed to demand the dehumanization of those enslaved.

By the 19th century, racism had matured and spread around the world. In many countries, leaders began to think of the ethnic components of their own societies, usually religious or language groups, in racial terms and to designate “higher” and “lower” races. Those seen as the low-status races, especially in colonized areas, were exploited for their labour, and discrimination against them became a common pattern in many areas of the world. The expressions and feelings of racial superiority that accompanied colonialism generated resentment and hostility from those who were colonized and exploited, feelings that continued even after independence.

Since the mid-20th century many conflicts around the world have been interpreted in racial terms even though their origins were in the ethnic hostilities that have long characterized many human societies (e.g., Arabs and Jews, English and Irish). Racism reflects an acceptance of the deepest forms and degrees of divisiveness and carries the implication that differences between groups are so great that they cannot be transcended .

Racism elicits hatred and distrust and precludes any attempt to understand its victims. For that reason, most human societies have concluded that racism is wrong, at least in principle, and social trends have moved away from racism. Many societies have begun to combat racism by raising awareness of racist beliefs and practices and by promoting human understanding in public policies, as does the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , set forth by the United Nations in 1948.

In the United States, racism came under increasing attack during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, and laws and social policies that enforced racial segregation and permitted racial discrimination against African Americans were gradually eliminated. Laws aimed at limiting the voting power of racial minorities were invalidated by the Twenty-fourth Amendment (1964) to the U.S. Constitution , which prohibited poll taxes , and by the federal Voting Rights Act (1965), which required jurisdictions with a history of voter suppression to obtain federal approval (“preclearance”) of any proposed changes to their voting laws (the preclearance requirement was effectively removed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 [ see Shelby County v. Holder ]). By 2020 nearly three-quarters of the states had adopted varying forms of voter ID law , by which would-be voters were required or requested to present certain forms of identification before casting a ballot. Critics of the laws, some of which were successfully challenged in the courts, contended that they effectively suppressed voting among African Americans and other demographic groups. Other measures that tended to limit voting by African Americans were unconstitutional racial gerrymanders , partisan gerrymanders aimed at limiting the number of Democratic representatives in state legislatures and Congress, the closing of polling stations in African American or Democratic-leaning neighbourhoods, restrictions on the use of mail-in and absentee ballots, limits on early voting, and purges of voter rolls.

Despite constitutional and legal measures aimed at protecting the rights of racial minorities in the United States, the private beliefs and practices of many Americans remained racist, and some group of assumed lower status was often made a scapegoat. That tendency has persisted well into the 21st century.

Because, in the popular mind, “race” is linked to physical differences among peoples, and such features as dark skin colour have been seen as markers of low status, some experts believe that racism may be difficult to eradicate . Indeed, minds cannot be changed by laws, but beliefs about human differences can and do change, as do all cultural elements.

- Contributors

- Valuing Black Lives

- Black Issues in Philosophy

- Blog Announcements

- Climate Matters

- Genealogies of Philosophy

- Graduate Student Council (GSC)

- Graduate Student Reflection

- Into Philosophy

- Member Interviews

- On Congeniality

- Philosophy as a Way of Life

- Philosophy in the Contemporary World

- Precarity and Philosophy

- Recently Published Book Spotlight

- Starting Out in Philosophy

- Syllabus Showcase

- Teaching and Learning Video Series

- Undergraduate Philosophy Club

- Women in Philosophy

- Diversity and Inclusiveness

- Issues in Philosophy

- Public Philosophy

- Work/Life Balance

- Submissions

- Journal Surveys

- APA Connect

What Is Racism?

Below is the audio recording of Kwame Anthony Appiah’s Berggruen Prize Lecture, given at the 2024 Pacific Division Meeting and made possible through the generosity of the Berggruen Institute. The talk is titled “What Is Racism?” and in it Appiah uses the murder of George Floyd as a starting point to explore the broader issue of racism in America. He notes the lack of consensus on the definition of racism and proposes an account of it as an ideology involving beliefs in inherited racial essences and the superiority or inferiority of different races. This ideology then manifests in discriminatory attitudes, feelings, and institutional practices that serve to oppress certain racial groups. Appiah argues that to address racism, we must dismantle the racist ideologies that sustain this oppression in order to build a more just and equitable society.

The audio of the lecture is available here:

“ What Is Racism? ” by Kwame Anthony Appiah

Kwame Anthony Appiah is Professor of Philosophy and Law at New York University and Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Philosophy and the University Center Human Values Emeritus at Princeton University. He holds a BA and a PhD in Philosophy from Clare College, Cambridge University. Appiah has served as president of the APA’s Eastern Division (2007–2008) and chair of the APA board of officers (2008–2011), as well as on the boards of the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, New York’s Public Library, the Public Theater, and the PEN American Center. In 2012, President Obama presented him with the National Humanities Medal. His publications include Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers , Lines of Descent: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity , As If: Idealization and Ideals , and The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity , along with three novels.

Learn more about the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture and Berggruen Prize Essay Competition .

- Berggruen Prize Lecture

- Kwame Anthony Appiah

- Pacific Division

- philosophy of race

RELATED ARTICLES

Central apa secretary-treasurer retrospective, inside the apa: things you didn’t know were on the apa website, apa announces spring 2024 prize winners, apa announces new ai2050 prizes, meet the apa: devin brymer, meet the apa: mark van roojen, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

WordPress Anti-Spam by WP-SpamShield

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Advanced search

Posts You May Enjoy

Rplaceuniverse: teen-found organization transforming teen insights into philosophical theories, musings on service work, fit, and graduate school education, philosophy and current affairs: the russia-ukraine war, “in order to live we must synthesize thought and feeling”: reflections..., results of the recent apa elections, robert hartman wins the 2020 routledge, taylor & francis prize, c. thi nguyen awarded the 2020 article prize.

What Is Racism: Definition and Examples

Getty Images / FotografiaBasica

- Understanding Race & Racism

- People & Events

- Law & Politics

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

Dictionary Definition of Racism

Sociological definition of racism, discrimination today.

- Internalized and Horizontal Racism

Reverse Racism

- M.A., English and Comparative Literary Studies, Occidental College

- B.A., English, Comparative Literature, and American Studies, Occidental College

What is racism, really? The use of the term racism has become so popular that it’s spun off related terms such as reverse racism, horizontal racism, and internalized racism .

Let’s start by examining the most basic definition of racism—the dictionary meaning. According to the American Heritage College Dictionary, racism has two meanings. This resource first defines racism as, “The belief that race accounts for differences in human character or ability and that a particular race is superior to others” and secondly as, “ Discrimination or prejudice based on race.”

Examples of the first definition abound throughout history. When enslavement was practiced in the United States, Black people were not only considered inferior to White people but also regarded as property rather than human beings. During the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, lawmakers agreed that enslaved individuals were to be considered three-fifths people for the purposes of taxation and representation. Generally speaking, during the era of enslavement, Black people were deemed intellectually inferior to White people as well. Some Americans believe this still today.

In 1994, a book called "The Bell Curve" posited that genetics were to blame for Black people traditionally scoring lower than White people on intelligence tests. The book was attacked by many including New York Times columnist Bob Herbert, who argued that social factors were responsible for the differential, and Stephen Jay Gould, who argued that the authors made conclusions unsupported by scientific research.

However, this pushback has done little to stifle racism, even in academia. In 2007, Nobel Prize-winning geneticist James Watson ignited similar controversy when he suggested that Black people were less intelligent than White people.

The sociological definition of racism is much more complex. In sociology, racism is defined as an ideology that prescribes statuses to racial groups based on perceived differences. Though races are not inherently unequal, racism forces this narrative. Genetics and biology do not support or even suggest racial inequality, contrary to what many people—often even scholars—believe. Racial discrimination, based on manufactured inequalities, is a direct product of racism that brings these notions of difference into reality. Institutional racism permits inequality in legislation, education, public health, and more. Racism is allowed to spread further through the racialization of systems that affect nearly every aspect of life, and this combined with widespread discrimination results in racism that is systemic—allowed to exist by society as a whole and internalized by a majority to some extent.

Racism creates power dynamics that follow these patterns of perceived imbalance, which are exploited in order to preserve feelings of superiority in the "dominant" race and inferiority in the "subservient" race, even to blame the victims of oppression for their own situations. Unfortunately, these victims often unwittingly play a role in the continuation of racism. Scholar Karen Pyke points out that "all systems of inequality are maintained and reproduced, in part, through their internalization by the oppressed." Even though racial groups are equal at the most basic level, groups assigned lesser statuses are oppressed and treated as though they are not equal because they are perceived not to be. Even when subconsciously held, these beliefs serve to further divide racial groups from one another. Radical versions of racism such as white supremacy make overt the unspoken ideologies within racism: that certain races are superior to others and should be allowed to hold more societal power.

Racism persists in modern society, often taking the form of discrimination. Case in point: Black unemployment has consistently soared above White unemployment for decades. Why? Numerous studies indicate that racism advantaging White people at the expense of Black people contributes to unemployment gaps between races.

For example, in 2003, researchers at the University of Chicago and MIT released a study involving 5,000 fake resumes, finding that 10% of resumes featuring “Caucasian-sounding” names were called back compared to just 6.7% of resumes featuring “Black-sounding” names. Moreover, resumes featuring names such as Tamika and Aisha were called back just 5% and 2% of the time. The skill level of the faux Black candidates made no impact on callback rates.

Internalized Racism and Horizontal Racism

Internalized racism is not always or even usually seen as a person from a racial group in power believing subconsciously that they are better than people of other races. It can often be seen as a person from a marginalized group believing, perhaps unconsciously, that White people are superior.

A highly publicized example of this is a 1940 study devised by Dr. Kenneth and Mamie to pinpoint the negative psychological effects of segregation on young Black children. Given the choice between dolls completely identical in every way except for their color, Black children disproportionately chose dolls with white skin, often even going so far as to refer to the dark-skinned dolls with derision and epithets.

In 2005, teen filmmaker Kiri Davis conducted a similar study, finding that 64% of Black girls interviewed preferred White dolls. The girls attributed physical traits associated with White people, such as straighter hair, with being more desirable than traits associated with Black people.

Horizontal racism occurs when members of minority groups adopt racist attitudes toward other minority groups. An example of this would be if a Japanese American prejudged a Mexican American based on the racist stereotypes of Latinos found in mainstream culture.

“Reverse racism” refers to supposed anti-White discrimination. This term is often used in conjunction with practices designed to help people of color, such as affirmative action .

To be clear, reverse racism does not exist. It’s also worth noting that in response to living in a racially stratified society, Black people sometimes complain about White people. Typically, such complaints are used as coping mechanisms for withstanding racism, not as a means of placing White people into the subservient position Black people have been forced to occupy. And even when people of color express or practice prejudice against White people, they lack the institutional power to adversely affect the lives of White people.

- Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. " Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination ." American Economic Review , vol. 94, no. 4, Sep. 2004, pp. 991–1013, doi:10.1257/0002828042002561

- Clair, Matthew, and Jeffrey S. Denis. " Sociology of Racism ." The International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences , 2015, pp. 857–863, doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32122-5

- Pyke, Karen D. " What Is Internalized Racial Oppression and Why Don't We Study It? Acknowledging Racism's Hidden Injuries ." Sociological Perspectives , vol. 53, no. 4, Dec. 2010, pp. 551–572, doi:10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.551

- Does Reverse Racism Exist?

- What Is the Definition of Internalized Racism?

- What Is the Definition of Passing for White?

- Understanding 4 Different Types of Racism

- Understanding Racial Prejudice

- Racial Bias and Discrimination: From Colorism to Racial Profiling

- The Roots of Colorism, or Skin Tone Discrimination

- Five Myths About Multiracial People in the U.S.

- Racial Profiling and Why it Hurts Minorities

- Why the Effects of Colorism Are So Damaging

- A Guide to Understanding and Avoiding Cultural Appropriation

- Understanding the Difference Between Race and Ethnicity

- How Racism Affects Children of Color in Public Schools

- Blockbusting: When Black Homeowners Move to White Neighborhoods

- Why Racial Profiling Is a Bad Idea

- Scientific and Social Definitions of Race

Racism: What it is, how it affects us and why it’s everyone’s job to do something about it

Bray lecturer Camara Jones addresses racism as a public health crisis

- Post author By Kathryn

- Post date October 5, 2020

By Kathryn Stroppel

In 2018, the CDC found a 16% difference in the mortality rates of Blacks versus whites across all ages and causes of death. This means that white Americans can sometimes live more than a decade longer than Blacks.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the discrepancy in health outcomes has only grown. Michigan’s population, for instance, is 14% Black, yet near the start of the pandemic, African Americans made up 35% of cases and 40% of deaths.

Because of this discrepancy in health outcomes, many scientists and government officials, including former American Public Health Association President Camara Jones, MD, PhD, MPH ; more than 50 municipalities nationwide; and a handful of legislators are attempting to root out this inequality and call it what it is: A public health crisis.

Dr. Jones, a nationally sought-after speaker and the college’s 2020 Bray Health Leadership Lecturer, has been engaged in this work for decades and says the time to act is now.

“The seductiveness of racism denial is so strong that if people just say a thing, six months from now they may forget why they said it. But if we start acting, we won’t forget why we’re acting,” she says. “That’s why it’s important right now to move beyond just naming something or putting out a statement making a declaration, but to actually engage in some kind of action.”

Synergies editor Kathryn Stroppel talked with Dr. Jones about this unique time in history, her work, racism’s effects on health and well-being, and what we can all do about it.

Let’s start with definitions. What is racism and why is important to acknowledge ‘systemic’ racism in particular?

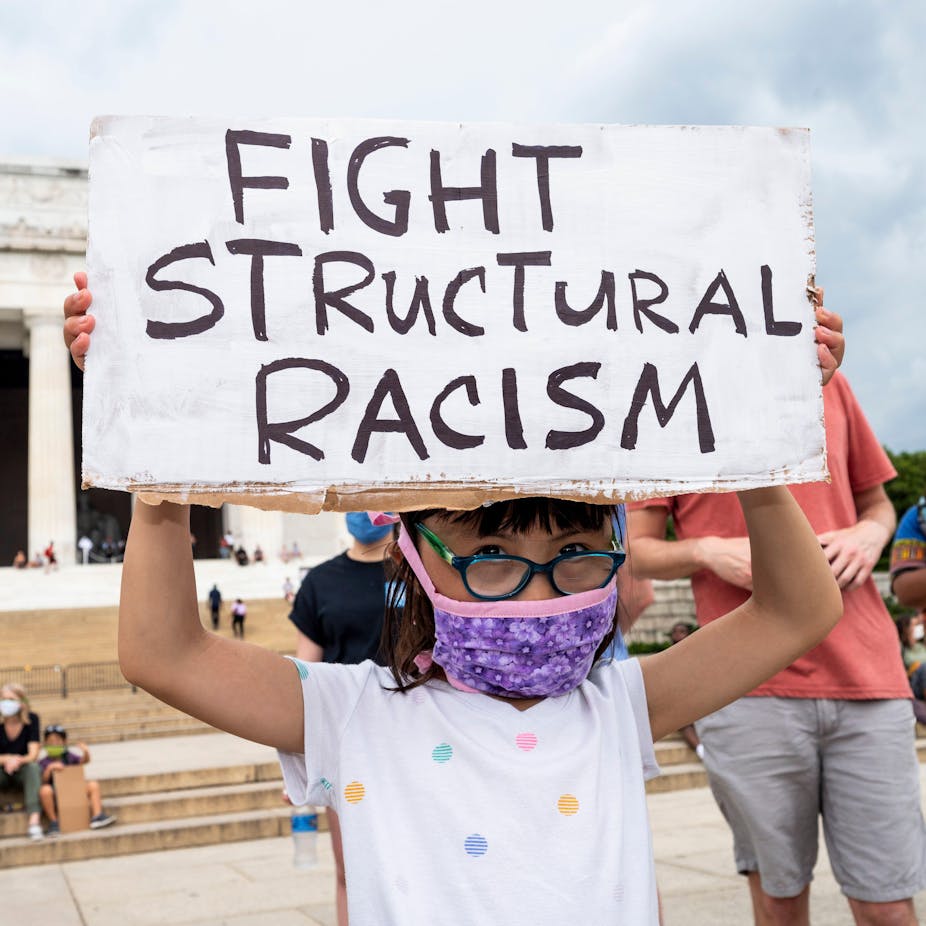

“Racism is a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we call race, that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.

“The reason that people are using those words ‘systemic’ or ‘structural racism’ is that sometimes if you say the word racism, people think you’re talking about an individual character flaw, or a personal moral failing, when in fact racism is a system.

“It’s not about trying to divide the room into who’s racist and who’s not. I am clear that the most profound impacts of racism happen without bias.

“The most profound impacts of racism are because structural racism has been institutionalized in our laws, customs and background norms. It does not require an identifiable perpetrator. And it most often manifests as inaction in the face of need.”

Why did you want to give the 2020 Bray Lecture?

“I’ve been doing this work for decades, and all of a sudden, now that we are recognizing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color, and after the murder of George Floyd and all of the other highly publicized murders that have been happening, more and more people are interested in naming racism and asking how is racism is operating here and organizing and strategizing to act. I wish I could accept every invitation.”

What do you hope people take away from your lecture?

“When I was president of the American Public Health Association in 2016, I launched a national campaign against racism with three tasks: To name racism; to ask, ‘how is racism operating here?’; and then to organize and strategize to act.

“Naming racism is urgently important, especially in the context of widespread denial that racism exists. We have to say the word ‘racism’ to acknowledge that it exists, that it’s real and that it has profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation.

“We have to be able to put together the words ‘systemic racism’ and ‘structural racism’ to able to be able to affirm that Black lives matter. That’s important and necessary, but insufficient.

“I then equip people with tools to address how racism operates by looking at the elements of decision making, which are in our structures, policies, practices, norms and values, and the who, what, when and where of decision making, especially who’s at the table and who’s not.

“After you have acknowledged that the problem exists, after you have some kind of understanding of what piece of it is in your wheelhouse and what lever you can pull, or who you know, you organize, strategize and collectively act.”

You’re known for using allegory to explain racism. Why is that?

“I use allegory because that’s how I see the world. There are two parts to it. One is that I’m observant. If I see something and if it makes me go, ‘Hmm,’ I just sort of store that away. And the second part is that I am a teacher. I’ve been telling a gardening allegory since before I started teaching at Harvard, but I later expanded that in order to help people understand how to contextualize the three levels of racism.

“As an assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, I developed its first course on race and racism. As I’m teaching students and trying to help them understand different elements, different aspects of race, racism and anti-racism, I found myself using these images naturally just to explain things, and then I recognized that allegory is sort of a superpower.

“It makes conversations that might be otherwise difficult more accessible because we’re not talking about racism between you and me, we’re talking about these two flower pots and the pink and red seed, or we’re talking about an open or closed sign, or we’re talking about a conveyor belt or a cement factory. And so I put the image out there to suggest the ways that it can help us understand issues of race and racism. And then other people add to it or question certain parts and it becomes our collective image and our tool, not just mine.”

What should white people in particular see as their role and responsibility in this system?

“All of us need to recognize that racism exists, that it’s a system, that it saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources, and that we can do something about it. White people in particular have to recognize that acknowledging their privilege is important – that your very being gives you the benefit of the doubt.

“White people who don’t want to walk around oblivious to their privilege or benefit from a racist society need to understand how to use their white privilege for the struggle.”

“An example: About six years ago now, in McKinney, Texas, outside of Dallas, we came to know that there was a group of pre-teens who wanted to celebrate a birthday at a neighborhood swimming pool. The people who were at the pool objected to them being there and called the police. And what we saw was a white police officer dragging a young Black girl by her hair, and then he sat on her, and the young Black boys were handcuffed sitting on the curb.

“The next day on TV, I heard a young white boy who was part of the friend group saying it was almost as if he were invisible to the police. He saw what was happening to his friends and he could have run home for safety, but instead, he recognized his white skin privilege. He stood up and videotaped all that was going on.

“So, the thing is not to deny your white skin privilege or try to shed it, the thing is to recognize it and use it. Then as you’re using it, don’t think of yourself as an ally. Think of yourself as a compatriot in the struggle to dismantle racism. We have to recognize that if you’re white, your anti-racist struggle is not for ‘them.’ It’s for all of us.”

Why did you transition from medicine to public health?

“Because there’s a difference between a narrow focus on the individual and a population-based approach. I started as a family physician, but then wanted to do public health because it made me sad to fix my patients up and then send them back out into the conditions that made them sick.

“I wanted to broaden my approach and really understand those conditions that make people sick or keep them well. From there, the data doesn’t necessarily turn into policy. So, I sort of went into the policy aspect of things. And then you recognize that you can have all the policy you want, but sometimes the policy is not enacted by politicians. So now I am considering maybe moving into politics.”

Speaking of politics, when engaging in discussions around racism and privilege, people will sometimes try to shut down the conversation for being ‘political.’ Is racism political?

“Racism exists. It’s foundational in our nation’s history. It continues to have profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation. To describe what is happening is not political. If people want to deny what exists, then maybe they have political reasons for doing that.”

What are your thoughts on COVID-19 and our country’s approach to dealing with the virus?

“The way we’ve dealt with COVID-19 is a very medical care approach. We need to have a population view where you do random samples of people you identify as asymptomatic as well as symptomatic.

“When you have a narrow medical approach to testing, you can document the course of the pandemic, but you can’t do anything to change it.

“With a population-based approach we already know how to stop this pandemic: It’s stay-at-home orders, mask wearing, hand washing and social distancing.

“This very seductive, narrow focus on the individual is making us scoff at public health strategies that we could put in place and is hamstringing us in terms of appropriate responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In terms of race, COVID-19 is unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation. This is the time to name racism as the cause of those things. The overrepresentation of people of color in poverty and white people in wealth is not happenstance.”

We have work to do. Learn how the college is transforming academia for equity .

- Tags COVID , Public Health

Racism, bias, and discrimination

Racism is a form of prejudice that generally includes negative emotional reactions to members of a group, acceptance of negative stereotypes, and racial discrimination against individuals; in some cases it can lead to violence.

Discrimination refers to the differential treatment of different age, gender, racial, ethnic, religious, national, ability identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic, and other groups at the individual level and the institutional/structural level. Discrimination is usually the behavioral manifestation of prejudice and involves negative, hostile, and injurious treatment of members of rejected groups.

Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology

Resources from APA

Racial Equity Action Plan Progress and Impact Report

Update on APA’s efforts toward dismantling systemic racism in psychology and society

Empowering youth of color

The psychologist is one of 12 global leaders who received a $20 million grant from Melinda French Gates.

Implicit theories concerning the intelligence of individuals with Down syndrome

Think professionals who work with people with disabilities are immune to bias? Think again

Combating stigma against patients

How clinicians can overcome bias and provide better treatment

More resources about racism

What APA is doing

Race, ethnicity, and religion

APA Services advocates for the equal treatment of people of all races, religions, and ethnicities, as well as funding for federal programs that address health disparities in these groups.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion

Inclusive language guidelines

APA’s commitment to addressing systemic racism

APA’s action plan for addressing inequality

APA’s apology to people of color in the U.S.

Confronting past wrongs and building an equitable future

Dismantling Everyday Discrimination

Perspectives on Hate

Attachment-Based Family Therapy for Sexual and Gender Minority Young Adults and Their Non-Accepting Parents

Addressing Cultural Complexities in Counseling and Clinical Practice

Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress

Magination Press children’s books

Algo Le Pasó a Mi Papá

Bernice Sandler and the Fight for Title IX

Something Happened to My Dad

Lulu the One and Only

Something Happened in Our Town

Journal special issues

Police, Violence, and Social Justice

Decolonialism From a Latin Perspective

Understanding, Unpacking and Eliminating Health Disparities

The Impact of Race on Psychological Processes

Asian America and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Ethnic psychological associations

- American Arab, Middle Eastern, and North African Psychological Association

- The Association of Black Psychologists

- Asian American Psychological Association

- National Latinx Psychological Association

- Society of Indian Psychologists

Related resources

- Protecting and Defending our People: Nakni tushka anowa (The Warrior’s Path) Final Report (PDF, 8.64MB) APA Division 45 Warrior’s Path Presidential Task Force (2020)

- Society for Community Research and Action (APA Division 27) Antiracism / Antioppression email series

- Society of Counseling Psychology (APA Division 17) Social justice resources

- Talking About Race | National Museum of African American History and Culture Tools and guidance for discussions of race

- InnoPsych therapists of color search

What is racism?

Definition of racism.

Racism is the process by which systems and policies, actions and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race. Racism is more than just prejudice in thought or action. It occurs when this prejudice – whether individual or institutional – is accompanied by the power to discriminate against, oppress or limit the rights of others.

Historical context of racism in Australia

Race and racism have been central to the organisation of Australian society since European colonisation began in 1788. As the First Peoples of Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have borne the brunt of European colonisation and have a unique experience of racism. The process of colonisation, and the beliefs that underpin it, continue to shape Australian society today.

Racism adapts and changes over time , and can impact different communities in different ways, with racism towards different groups intensifying in different historical moments . An example of this is the spike in racism towards Asian and Asian-Australian people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

How does racism operate?

Racism includes all the laws, policies, ideologies and barriers that prevent people from experiencing justice, dignity , and equity because of their racial identity. It can come in the form of harassment, abuse or humiliation, violence or intimidating behaviour. However, racism also exists in systems and institutions that operate in ways that lead to inequity and injustice.

The Racism. It Stops With Me website contains a list of ' Key terms ' that unpack some of the different ways that racism is expressed.

Lets Talk About Racism

Further reading

- Commit to learning to address racism in a meaningful way on the It Stops With Me website

- Understand why racism is a problem?

- Explore who experiences racism?

- Review a guide to addressing spectator racism in sports

- Watch the Kep Enderby Memorial Lecture 2023 "Racism in Sport"

- Explore human rights teaching resources relating to racism

- Understand the Australian Human Right's Commission work on Race Discrimination

- Review the Australian Human Rights Commission's Anti-Racism Framework

More Information on Racial Discrimination

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Fight to Redefine Racism

Sixteen years ago, in 2003, the student newspaper at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, a historically black institution in Tallahassee, published a lively column about white people. “I don’t hate whites,” the author, a senior named Ibram Rogers, wrote. “How can you hate a group of people for being who they are?” He explained that “Europeans” had been “socialized to be aggressive people,” and “raised to be racist.” His theory was that white people were fending off racial extinction, using “psychological brainwashing” and “the AIDS virus.” Perhaps the most incendiary line appeared at the end, after the author’s byline and e-mail address: “Ibram Rogers’ column will appear every Wednesday.”

As it turned out, that final claim, like a few of the claims that preceded it, was not quite accurate. The column caused a stir, and Rogers was summoned to see the editor of the local newspaper, the Tallahassee Democrat , where he was an intern. The editor demanded that Rogers discontinue his column, and Rogers agreed under protest, though he resolved to continue his examination of race in America, which became his life’s work. He eventually earned a Ph.D. in African-American studies from Temple, and gained a reputation in the field, along with some new names. He changed his middle name from Henry to Xolani, which is Zulu for “be peaceful,” after learning the history of Prince Henry the Navigator, a fifteenth-century Portuguese explorer who helped pioneer the African slave trade. And at his wedding, in 2013, he and his wife, Sadiqa, told their guests that they had chosen a new last name: Kendi, which means “the loved one” in the Kenyan language of Meru. In 2016, as Ibram X. Kendi, he published “ Stamped from the Beginning ,” a voluminous, sober-minded book that aimed to present “the definitive history of racist ideas in America.”

In the thirteen years since his abortive college-newspaper column, Kendi had become ever more convinced that racism, not race, was the central force in American history, and so he reached back to 1635 to show how malleable racism could be. The preachers who justified slavery used racist arguments, he wrote, but so did many of the abolitionists—the ubiquity of racism meant that no one was immune to its seductive power, including black people. In his view, the pioneering black sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois was propping up racist ideas in 1897, when he condemned “the immorality, crime, and laziness among the Negroes.” So, too, was Barack Obama , when, as a Presidential candidate in 2008, he decried “the erosion of black families.” Although Obama noted that this erosion was partly due to “a lack of economic opportunity,” he also made an appeal to black self-reliance, saying that members of the African-American community needed to face “our own complicity in our condition.” Kendi saw statements like these as reflections of a persistent but delusional idea that something is wrong with black people. The only thing wrong, he maintained, was racism, and the country’s failure to confront and defeat it.

“Stamped from the Beginning” was an unreservedly militant book that received a surprisingly warm reception. Amid a series of police shootings of African-Americans during President Obama’s second term, “ Black lives matter ” became a rallying cry and then a movement, and helped push racism to the front of the progressive conversation. By the time Obama left office, in 2017, polls showed record-high support among Democrats for “special treatment” to help African-Americans, and for the idea that “racial discrimination” is the main obstacle to racial parity. A prominent cohort of writers, led by Ta-Nehisi Coates, was calling for a serious reckoning with racism, and with the way racist policies had worked to depress black earnings and constrain black life. In this climate, Kendi’s book was celebrated as a well-timed contribution to a national conversation. It won a National Book Award and transformed Kendi into a leading public intellectual. His scholarly project has been institutionalized: Kendi is now the founding director of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at American University, in Washington, D.C.

In modern American political discourse, racism connotes hatred, and just about everyone claims to oppose it. But many on the contemporary left have pursued a more active opposition, galvanized by the rise of Donald Trump, who has been eager to denounce black politicians but reluctant to denounce white racists. In many liberal circles, a movement has gathered force: a crusade against racism and other isms. It is a fierce movement, and sometimes a frivolous one, aiming the power of its outrage at excessive prison sentences, tasteless Halloween costumes, and many offenses in between. This movement seems to have been particularly transformative among white liberals, who are now, by some measures, more concerned about racism than African-Americans are. One survey found that white people who voted for Hillary Clinton felt warmer toward black people than toward their fellow-whites.

Most white people in America are not liberals, of course, and so the campaign against racism has often taken the form of an intra-white conflict. One of the most prominent combatants is Robin DiAngelo, a white workplace-diversity trainer, available to help organizations teach their employees to be more sensitive to race. Last year, DiAngelo published “ White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism ,” a reflection on her career and her cause. “White identity is inherently racist,” she writes. “I strive to be ‘less white.’ ” She cites Kendi as an authority, even if she sometimes seems closer in spirit to Ibram Rogers, the undergraduate. But, then, Kendi himself is in an instructive mood: his new work presents itself as a how-to book, although, in a little more than two hundred absorbing pages, it’s also a manifesto and, from time to time, a memoir. It is titled “ How to Be an Antiracist ,” and in it Kendi explains how he became one, which means explaining how he used to be (as he currently sees it) a racist. Kendi is convinced that racism can be objectively identified, and therefore fought, and one day vanquished. He argues that we should stop thinking of “racist” as a pejorative, and start thinking of it as a simple description, so that we can join him in the difficult work of becoming antiracists. “One either endorses the idea of a racial hierarchy as a racist or racial equality as an antiracist,” Kendi writes, adding that it isn’t possible to be simply “not racist.” He thinks that all of us must choose a side; in fact, he thinks that we are already choosing, all the time.

The modern battle against racism, as many people have observed, is driven by a kind of sacred fervor, and in “How to Be an Antiracist” Kendi makes this link explicit. “I cannot disconnect my parents’ religious strivings to be Christian from my secular strivings to be an antiracist,” he writes. Indeed, Christianity and antiracism were intimately connected for his parents. They were inspired by Tom Skinner, a fiery black evangelist who preached the gospel of “Jesus Christ the Radical,” and by James H. Cone, one of the originators of black-liberation theology. Kendi’s parents taught him black pride, and he took these lessons seriously. As Kendi tells it, his parents’ belief in black pride led them to embrace black self-reliance, a doctrine that urged black people to overcome the legacy of racism by working hard and doing well. Kendi bitterly recalls a speech he gave at an oratory contest in high school, decrying the bad habits of black youth. “They think it’s okay not to think,” he said. “They think it’s okay to be those who are most feared in society.” Kendi won the competition, but he now regards the speech as shamefully racist, because it blamed black people for their own failures. “I was a dupe, a chump,” he writes. He argues that the idea of black underachievement lends support for anti-black policies, which in turn help perpetuate the conditions that inspire speeches like his.

By the time he got to college, Kendi was outspokenly pro-black: he “pledged to date only Dark women,” as a personal protest against standards of beauty that favor lighter skin. His infamous newspaper column was actually a fairly mild representation of his collegiate beliefs, which included a dalliance with the notion that white people were literally aliens, and a conviction that racist whites and treacherous blacks had formed a sinister partnership—“a team of ‘them niggers’ and White folks.” But as he studied African-American history he came to believe that the basic story was even simpler than he had thought. American history, he discovered, was “a battle between racists and antiracists.”

In “Stamped from the Beginning,” Kendi divided the racists into two kinds, segregationists and assimilationists. Historically, segregationists argued that black people were inherently defective or dangerous, and needed to be kept under control. Assimilationists sounded kinder: they often fought against black oppression, but they also argued that black people needed to change their behavior—their culture—in order to catch up to white people and assimilate into white society. In 1834, the American Anti-Slavery Society issued a pamphlet of admonishment:

We have noticed with sorrow, that some of the colored people are purchasers of lottery tickets, and confess ourselves shocked to learn that some persons, who are situated to do much good, and whose example might be most salutary, engage in games of chance for money and for strong drink.

Sometimes these lectures were intended as a political strategy, on the theory that civil rights would be easier to win if black Americans were perceived to be working hard. And sometimes, especially in the twentieth century, they were intended as acknowledgments of the limits of politics. In Kendi’s view, though, talk of failures in culture or conduct supposes that black people are somehow to blame for the effects of racism—as if they could have chosen, instead, to be unaffected by it. He thinks that it is both unfair and impractical to suggest that black communities must somehow heal themselves before the government can intervene. Ranging across the centuries, “Stamped” identified segregationists, assimilationists, and antiracists with a confident clarity that was also the book’s greatest weakness, because it reduced complicated lives to a series of pass-fail tests. Kendi noted with satisfaction that when Du Bois was in his sixties he concluded that black people would never “break down prejudice” through virtuous comportment—thus becoming, at last, an antiracist.

Kendi’s position has radical implications: in ruling out criticism of black culture or black behavior, it stipulates that any problems must be either fictional or the result of contemporary discrimination. If you reject “assimilationism,” then you can’t suggest, as Obama did, that centuries of racism have eroded the black nuclear family. You might try to show, instead, that black men are often shut out of the labor market, which makes them less likely to marry. Or you might conclude that the nuclear family is merely one cultural ideal among others, and not one to be universally preferred.

In the case of education, Kendi’s commitment to antiracist thinking leads him to dispute the existence of an “achievement gap” between white and black students. Black students may, on average, get lower scores on standardized tests, and drop out of high school at higher rates. But such metrics, he argues in “How to Be an Antiracist,” are themselves racist, devised to “degrade” and “exclude” black students; he suggests that a “low-testing” black student and a “high-testing” white student may simply be demonstrating “different kinds of achievement rather than different levels of achievement.” This celebration of difference comes to an end when it is time to judge the educational systems themselves. Kendi claims that “chronic underfunding of Black schools” does create “diminished”—and not merely “different”—“opportunities for learning.” Throughout the book, the idea is to judge unfair policies, while refusing to judge, as a group, the people who are subjected to them. Kendi believes that “individual Blacks have suffered trauma” in America, but he rejects the “racist” idea that “Blacks are a traumatized people.”

In successive chapters of “How to Be an Antiracist,” Kendi explains that there are many forms of racism: there is class racism, which conflates blackness with poverty, as well as gender racism, queer racism, and something called “space racism,” which is less exciting than it sounds—it has to do with the way people associate black neighborhoods, or spaces, with violence. “ ‘Racist’ and ‘antiracist,’ ” Kendi writes, “are like peelable name tags that are placed and replaced based on what someone is doing or not doing, supporting or expressing in each moment.” This suggests that people can change, as Kendi did, and as Du Bois did. But it also suggests that nonracist identity is contingent and unstable: we are all constantly peeling and resticking those nametags.

The result is to complicate the seemingly straightforward definitions Kendi offers in “How to Be an Antiracist.” For instance, he says that a policy can be either racist or antiracist; it is racist if it “produces or sustains racial inequity,” and a person is racist if he or she supports such a policy. But it may take many years to determine whether a policy produces or sustains racial inequity. For instance, some cities, including New York, generally forbid employers to ask job seekers about their criminal history, or to check their credit scores. These measures are designed in part to help African-American applicants, who may be more likely to have a criminal record, or to have poor credit. But some studies suggest that such prohibitions make black men, in general, less likely to be hired, perhaps because employers fall back on cruder generalizations. Are these laws and their supporters racist? In Kendi’s framework, the only possible answer is: wait and see.

Kendi’s definition of racism is decidedly unsentimental. If the word “racist” is capacious enough to describe both proud slaveholders and Barack Obama, and if it nevertheless must constantly be recalibrated in light of new policy research, then it may start to lose the emotional resonance that gives it power in the first place. There are a few moments in the book, though, when Kendi uses the word in a more colloquial, less rigorous sense. In the third grade, he had a white teacher who was, Kendi thought, quicker to call on white students, and quicker to punish nonwhite ones. One day, after seeing a shy black girl ignored, Kendi staged an impromptu sit-in at chapel. Years later, he says that the teacher was one of a number of “racist White people over the years who interrupted my peace with their sirens.” In a moment like this, “racist” seems less like a sticker and more like a tattoo: the word stings because it seems to convey something distasteful and profound about the person it describes. Even for the exponent of a new definition of racism, older ones are not easily banished.

It is no criticism of Kendi’s book to say that its title is misleading: he offers a provocative new way to think about race in America, but little practical advice. He wants readers to become politically active—to work to change public policy, and to “focus on power instead of people.” DiAngelo, the author of “White Fragility,” is unapologetically interested in people, particularly white people. She is perhaps the country’s most visible expert in anti-bias training, a practice that is also an industry, and from all appearances a prospering one. (Last year, anti-bias training was in the headlines when Starbucks closed its American stores for a day to conduct a company-wide lesson in “racial bias and discrimination.”) DiAngelo has been helping to lead workplace seminars since the nineties, and she has encountered some resistance. “When we try to talk openly and honestly about race,” she writes, “we are so often met with silence, defensiveness, argumentation, certitude, and other forms of pushback.” To explain this phenomenon, she coined the phrase “white fragility.”

DiAngelo holds a Ph.D. in multicultural education, but her most important credential is all the time she has spent in conference rooms. Where Kendi insists that racism can cloud anyone’s judgment, DiAngelo sees white people as singularly responsible. “Only whites have the collective social and institutional power and privilege over people of color,” she writes. She is unimpressed by white participants who swear they “treat everyone the same,” since that’s not possible. And she is alert to acts of racial transgression, as when a white woman uses what DiAngelo considers a “stereotypical” voice while telling an anecdote about an African-American. She thanks the woman for her “insight,” and then asks her to “consider not telling that story in that way again.” When the woman tries to defend herself, DiAngelo interrupts, speaking in the friendly but steely voice of administrative authority. “I am offering you a teachable moment,” she says.

Despite her sensitivity to racial power dynamics and to the reality of racial harassment, DiAngelo seems to have little interest in other workplace power dynamics, which might explain why she’s so surprised that many of the employees who attend her sessions aren’t happier to see her. DiAngelo is devoted to “challenging injustice,” but her corporate clients doubtless have their own priorities, and in any case it’s not clear what the effect of these seminars is. A group of social scientists has come up with the concept of “implicit bias,” which many trainers aim to diagnose and treat, even though there is scant evidence that implicit bias reliably affects behavior. DiAngelo mentions implicit bias, but, even more than Kendi, she is engaged in something that resembles a spiritual practice. In the sanctuaries she creates, one of the rules is that white people, especially white women, should not cry. It attracts too much attention, and it may upset nonwhite participants, by evoking the “long historical backdrop of black men being tortured and murdered because of a white woman’s distress.” If DiAngelo herself can’t resist, she performs a ritual of abnegation. “I try to cry quietly so that I don’t take up more space,” she writes, “and if people rush to comfort me, I do not accept the comfort.”

If there is scripture in DiAngelo’s world, it is the testimony of “people of color,” a term that usefully reduces all of humanity to two categories: white and other. Since white people are presumed to have “institutional power,” and therefore institutional responsibility, people of color function in this world as sages, speaking truths that white people must cherish, and not challenge. DiAngelo has sometimes received “feedback from people of color on my racist patterns and assumptions,” which she first found uncomfortable but eventually, as she grew more enlightened, came to find encouraging. “There is no way for me to avoid enacting problematic patterns,” DiAngelo writes, “so if a person of color trusts me enough to take the risk and tell me, then I am doing well.”

Once, when she offended a black client by referring to another black woman’s hair, DiAngelo discussed the incident with another white person (so as not to burden any other people of color), and then apologized to the offended party. She was forgiven her trespasses, but says she was prepared not to be. When you get feedback, especially from a person of color, what’s most important is to be grateful, and to try to do better. “Racism is complex,” she writes, “and I don’t have to understand every nuance of the feedback to validate that feedback.”

Unlike Kendi, who boldly defines racism, DiAngelo is endlessly deferential—for her, racism is basically whatever any person of color thinks it is. In the story she tells about the world, she and her fellow white people have all the power, and therefore all the responsibility to do the gruelling but transformative spiritual work she calls for. The story makes white people seem like flawed, complicated characters; by comparison, people of color seem good, wise, and perhaps rather simple. This narrative may be appealing to its target audience, but it doesn’t seem to offer much to anyone else. At least, that’s my interpretation, and perhaps DiAngelo will be grateful to hear it. After all, I am what she would call a person of color, and whatever I write surely counts as “feedback.” Maybe that means she is, indeed, doing well.

Part of what makes DiAngelo’s project surreal is the difference in scale between the historical injustices she invokes and the contemporary slights she addresses: on one side, the indescribable horror of lynching; on the other, careless crying. Kendi is less concerned about manners, and he strives to stay grounded in the brute facts of racial oppression. But his latest book, too, grows surreal at times, as he tries to reconcile the reality of black life in America with his own refusal to generalize.

“To be an antiracist is to realize there is no such thing as Black behavior,” he writes. He did not always grasp this. As a boy in Queens, Kendi found his life shaped by a fear of victimization. “I avoided making eye contact, as if my classmates were wolves,” he writes. “I avoided stepping on new sneakers like they were land mines.” In South Jamaica, his neighborhood, there was a local bully named Smurf, who pulled a gun on Kendi, and once, with Kendi watching, beat a boy unconscious on a city bus in order to steal his Walkman. This sounds terrifying, but Kendi now claims that his fears were delusional. “I believed violence was stalking me,” he writes, “but in truth I was being stalked inside my own head by racist ideas.” He thinks that prominent African-Americans can be unduly influenced by their rough childhoods. “We don’t write about all those days we were not faced with guns in our ribs,” he writes, at which point his antiracist project sounds less like a form of truthtelling and more like a kind of propaganda.

Crime poses a conceptual problem for Kendi. As most people know, African-Americans are greatly overrepresented among both victims and perpetrators of violent crime in America—indeed, this fact provides stark evidence of the country’s stubborn racial inequality. But Kendi’s approach disallows talk of criminality as a particular “problem” in black neighborhoods; he suggests that white neighborhoods have their own dangers, including crooked bankers (they “might steal your life savings”) and suburban traffic accidents; he even insists that there are a “disproportionate number of White males who engage in mass shootings,” although mass shootings account for a tiny percentage of gun deaths, and white people are not disproportionately likely to commit them. By the end of the section, the bully named Smurf seems less like a real person and more like a spectre: the personification of old racist ideas, come to life in the imagination of a fretful future scholar in Queens.

As it happens, there actually is a notorious tough guy named Smurf who grew up in Kendi’s neighborhood around the same time. He came to be known as Bang ’Em Smurf, a sometime rapper who, during the two-thousands, was an ally turned antagonist of 50 Cent, the hip-hop star. Not long ago, Bang ’Em Smurf self-published a memoir-cum-manifesto of his own, a seemingly unedited collection of fragments that provides a glimpse of the world that Kendi writes about. Smurf is evidently happy to think of himself as one of the “wolves” who roamed the neighborhood: his book is called “Wisdom of a Wolf,” and in it he recounts how he started stealing after his own bicycle was stolen, and explains the formative effect of seeing his mother stabbed when he was four or five. (According to Smurf, she fought back and won the fight.)

Smurf doesn’t mention a bookish militant named Ibram, but he does offer his own assessment of the neighborhood: “Where we are from Jamaica Queens the average youth doesn’t have hope or inspiration to live.” Smurf no longer lives there: in 2004, he was convicted of illegal-weapon possession, and after serving his sentence he was deported to Trinidad and Tobago, where he was born. But he is sure that things have grown only more difficult for young people in neighborhoods like Jamaica. Unlike Kendi, Smurf thinks that something is wrong there. “Most of these youth come from poverty,” he writes. “There is Lack of love and discipline in the household.” Smurf thinks that these families could and should do better, which means that, by Kendi’s definition, he is an assimilationist—and probably a space racist, too.

Kendi thinks that calls for racial uplift are doomed to failure, because they can never change enough minds, black or white, to alter either behavior or policy. They are prayer disguised as politics. But his approach demands a fair amount of faith, too, given that it requires a great part of the country to undergo a revolution in thought that took Kendi decades of study to achieve. Where DiAngelo says she is not sure that the country is making any progress toward reducing racism, Kendi thinks an antiracist world is possible. “Racism is not even six hundred years old,” he writes, tracing its origin to the fifteenth-century explorations of his former namesake Prince Henry. “It’s a cancer that we’ve caught early.” But the cure, he thinks, will start with policies, not ideas. He suggests that, just as ideologies of racial difference emerged after the slave trade in order to justify it, antiracist ideologies will emerge once we are bold enough to enact an antiracist agenda: criminal-justice reform, more money for black schools and black teachers, a program to fight residential segregation.

“Once they clearly benefit,” Kendi writes, “most Americans will support and become the defenders of the antiracist policies they once feared.” This is an inspiring prediction, although Kendi’s own scholarship provides less reason for optimism. But, if he is right, becoming an antiracist might entail a realization that our national conversation about race is largely beside the point. If it is possible, as Kendi insists, to change “racist policy” without first changing “racist minds,” then perhaps we needn’t worry quite so much about who thinks what, and why. Kendi wants us to see not only that there is nothing wrong with black people but that there is likewise nothing wrong with white people. “There is nothing right or wrong with any racial groups,” he writes. This is the bittersweet message hidden in his book: that, in the grand racial drama of America, every group is already doing the best it can. ♦

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Racial Discrimination — The Impact of Racism on the Society

Racism in Society, Its Effects and Ways to Overcome

- Categories: Racial Discrimination

About this sample

Words: 2796 |

14 min read

Published: Jun 10, 2020

Words: 2796 | Pages: 6 | 14 min read

Table of contents

Executive summary, the effects of racism in today’s world (essay), works cited.

- The current platform of social media has given many of the minorities their voice; they can make sure that the world can hear them and their opinions are made clear. This phenomenon is only going to rise with the rise of social media in the coming years.

- The diversity of race, culture and ethnicity that has been seen as a cause of rift and disrupt in the society in the past, will act as a catalyst for social development sooner rather than later, with the decrease in racism.

- Racist view of an individual are not inherited, they are learned. With that in mind, it is fair to assume that the coming generations will not be as critical of an individual’s race as the older generations have been.

- If people dismiss the concept of racial/ethnical evaluations and instead, evaluate an individual on one’s abilities and capabilities, the economic development will definitely have a rise.

- A lot of intra-society grievances and mishaps that are caused due to misconceptions of an ethnic group can be reduced as social interaction increases.

- As people from different ethnic backgrounds, coming from humble beginnings, discriminated throughout their careers, manage to emerge successful to the public platform, the racist train of thought is being exposed and will continue to do so. This will inspire people from any and every background, race, language, ethnicity to step forward and compete on the large scale.

- Racism and prejudice are at the root of racial profiling and that racial bias has been interweaved into the culture of most societies. However, these chains have grown much weaker as time has passed, to the point that they are in a fragile state.

- Another ray of hope that can be witnessed nowadays that people are no longer ashamed of their cultural identity. People now believe that their cultural background is in no way or form inferior to another and thus, worth defending. This will turn out to be a major factor in minimizing racism in the future.

- Because of the strong activism against racism, a new phenomenon has emerged that is color blindness, which is the complete disregard of racial characteristics in any kind of social situation.

- The world is definitely going in the right direction concerning the curse that is Racism; however, it is far too early to claim that humankind will completely rid itself of this vile malignance. PrescriptionsRacism is a curse that has plagued humanity since long. It has been responsible for multitudes of nefarious acts in the past and is causing a lot of harm even now, therefore care must be taken that this problem is brought under control as soon as possible so as not to hinder the growth of human societies. The following are some of the precautions, so to say, that will help tremendously in tackling this problem.

- The first and foremost step is to take this problem seriously both on an individual and on community level. Racism is something that can not be termed as a minor issue and dismissed. History books dictate that racism is responsible for countless deaths and will continue to claim the lives of more innocents unless it is brought under control with a firm hand. The first step to controlling it is to accept racism as a serious problem.

- Another problem is that many misconceptions or rumors that are dismissed by most people as a trivial detail are sometimes a big deal for other people, which might push them over the edge to commit a crime or some other injustice. So whenever there is an anomaly, a misconception or a misrepresentation of an individual’s, a group’s or a society’s ideas or beliefs, try to be the voice of reason rather than staying quiet about it. Decades of staying silent over crucial issues has caused us much harm and brought us to this point, staying silent now can only lead us to annihilation.

- One of most radical and effective solution to racial diversity is to turn it from something negative to something positive. Where previously, one does not talk to someone because of his or her cultural differences, now talk to them exactly because of that. If different cultures and races start taking steps, baby steps even, towards the goal of acquiring mutual respect and trust, racism can be held in check.

- On the national level, contingencies can be introduced and laws can be made that support cultural diversity and preach against anything that puts it in harm’s way. Taking such measures will make every single member of the society well aware of the scale of this problem and people will take it more seriously rather than ridiculing it.

- Finally, just as being racist was a part of the culture in the older generations, we need to make being anti-racist a part of our cultures. If our children, our youth grew up watching their elders and their role models dissing and undermining racism at every point of life, they will definitely adopt a lifestyle that will allow no racial discriminations in their life.

Methodology

Findings and results.

- Is racism justifiable?

- Is the current trend of racism increasing in your country?

- Do you have any acquaintances or friends that belong to a different ethnical background?

- Would you ever use someone’s race against them to win an argument?

- Would you agree to work in a diverse racial environment?

- Will humankind ever rid itself of racism?

- Have you ever taken any measures to abate racism?

- Racism has changed the relationship between people?

- Racial discriminations are apparent in our everyday life.

- One racial/ethnic group can be superior to another

- Racial/ethnic factors can change your perception of a person.

- Racial diversity can cause problems in one’s society.

- Racial or Ethnical conflict should be in cooperated into the laws of one’s society.

- Are you satisfied with the way different ethnic groups are treated in your society?

- ABC News. (2021). The legacy of racism in America. https://abcnews.go.com/US/legacy-racism-america/story?id=77223885

- British Broadcasting Corporation. (2021). Racism: What is it? https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/53498245

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Jones, M. R. (2020). Racism and the American economy. Harvard University.

- Gibson, K. L., & Oberg, K. (2019). What does racism look like today? National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2019/04/what-does-racism-look-like-today-feature/

- Hughey, M. W. (2021). White supremacy. The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Sociology.

- Jones, M. T., & Janson, C. (2020). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 41, 1-16.

- Krieger, N. (2019). Discrimination and racial inequities in health : A commentary and a research agenda. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S82-S85.

- Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2021). The psychology of racism: A review of theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 479-514.

- Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921-948.

- Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1152-1173.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 703 words

4 pages / 2004 words

1 pages / 1138 words

1 pages / 1265 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Racial Discrimination

The Black Student Alliance (BSA), along with other student groups, partnered together and held a protest on the steps of the campus’s central building, Mary Graydon Center. Consisting of 200 people, the protest was done to [...]

Obama's presence as the President of the United States is largely focused on the color of his skin. When he first ran, even the option of having a non-white president was seen as progress for America and its history of racism. [...]

This should perhaps be prefaced by a very obvious though sometimes understated recital of fact: racial equality or lack there of is not simply a matter of black and white. In fact, recent political rhetoric has brought to [...]

The issue of racial injustice has persisted for decades, deeply rooted in the fabric of society. As readers seek to engage with literature that addresses these pressing concerns, "The Hate U Give" emerges as a powerful fictional [...]

Oppression is the inequitable use of authority, law, or physical force to prevent others from being free or equal. Throughout the years, women have faced oppression and been forced to conform to gender roles. They have not been [...]

Prejudice is a pre-judgement formed about something or someone - but it is more than this as well? This complex idea is highlighted in the novel, To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee and the picture book Goin’ Someplace Special [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

10 Root Causes of Racism

According to Merriam-Webster , “racism” is the belief that a person’s race is a “fundamental determinant” of their traits and abilities. In the real world, this has led to persistent and insidious beliefs about superior and inferior races. Racism is also the “systemic oppression” of a racial group, giving other groups a social, economic, and political advantage. Both definitions matter in this article, which addresses ten root causes of racism (specifically against Black people) on a systemic and individual level.

Register now: 5 Anti-Racism Courses You Can Audit For Free

Cause #1: Greed and self-interest

Many experts believe racist beliefs were developed to justify self-interest and greed. For almost 400 years, European investors enslaved people through the Transatlantic slave trade to support the massive tobacco, sugar, and cotton industries in the Americas. Slavery was cheaper than indentured servitude, so slavery was a business decision, not a reflection of hatred or bigotry.