Website navigation

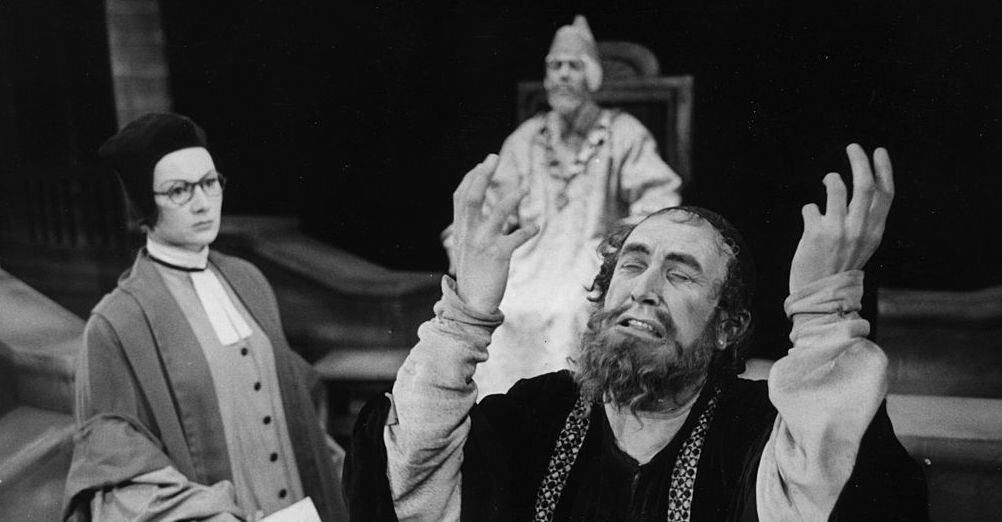

A Modern Perspective: The Merchant of Venice

By Alexander Leggatt

The Merchant of Venice is a comedy. Comedies traditionally end in marriage, and on the way they examine the social networks in which marriage is involved: the relations among families, among friends, among parents and children, and what in Shakespeare’s society were the all-important ties of money and property. Comedies also create onstage images of closed communities of right-thinking people, from which outsiders are excluded by being laughed at. If The Merchant of Venice has always seemed one of Shakespeare’s more problematic and disturbing comedies, this may be because it examines the networks of society more closely than usual, and treats outsiders—one in particular—with a severity that seems to go beyond the comic.

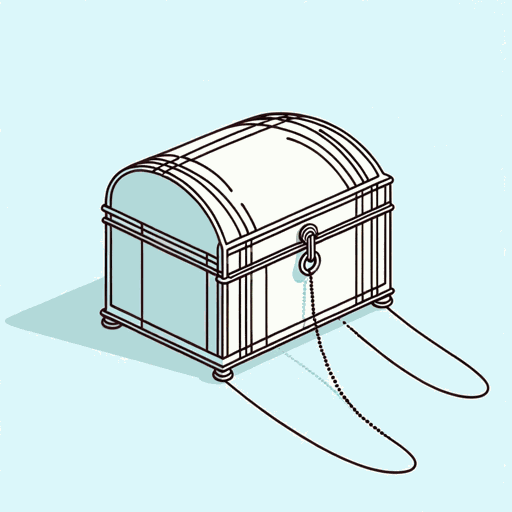

In the interweaving of the play’s stories we see a chain of obligations based on money. Bassanio needs money to pay his debts, and plans to get it by marrying the rich heiress Portia. To make money he needs to borrow money—from his friend Antonio, who borrows it from Shylock, who borrows it, according to the patter of his trade, from Tubal. Once Bassanio has won Portia she becomes part of the network, and the obligations become more than financial. She imposes on herself the condition that before her marriage is consummated, Antonio must be freed from his bond to Shylock; as she tells Bassanio, “never shall you lie by Portia’s side / With an unquiet soul” ( 3.2.318 –19). She takes on herself the task of freeing Antonio. As Bassanio must journey to Belmont and answer the riddle of the caskets, Portia must journey to Venice and answer the riddle of Shylock’s bond. Antonio thus becomes “bound” ( 4.1.425 ) to the young doctor (Portia) who saved him, and the only payment the doctor will take is Bassanio’s ring. Antonio now, in effect, has to borrow from Bassanio to pay Portia: it is at Antonio’s insistence that Bassanio reluctantly gives away the ring. Yet the ring represents Bassanio’s tie of loyalty to Portia, the husband’s obligation to be bound exclusively to his wife; she gives the ring, as Shylock gives money, with conditions attached:

Which, when you part from, lose, or give away,

Let it presage the ruin of your love,

And be my vantage to exclaim on you.

( 3.2.176 –78)

The line of obligation runs, like the play itself, from Venice to Belmont, then from Belmont to Venice, and back to Belmont again. The ring exemplifies the paradox of marriage: it binds two people exclusively to each other, yet it does so within a social network in which they have inevitable ties with other people, ties on which the marriage itself depends. Portia and Bassanio depend on Antonio, who is Portia’s chief rival for Bassanio’s affection. The story of the ring is based on paradoxes: Bassanio, in giving it to the young “doctor,” is betraying Portia at her own request, and giving her back her own. In the final scene Portia gives the ring to Antonio, who returns it to Bassanio, thus participating in a symbolic exchange that cements the marriage relationship from which he is excluded. As Portia’s ring comes back to Portia, then back to Bassanio, the line of obligation becomes at last a circle, the symbol at once of perfection and exclusion.

Portia is also bound to her father. When we first see her she is chafing at the way her father has denied her freedom of choice in marriage: “So is the will of a living daughter curbed by the will of a dead father” ( 1.2.24 –25). But by the end of that scene she is reconciled to her father’s will when she hears that her unwanted suitors have departed rather than face the test; and of course Bassanio, the man she wants—the man who visited Belmont in her father’s time ( 1.2.112 –21)—is the winner. The will of the dead father and the will of the living daughter are one. Portia sees the value of the test from her own point of view when she tells Bassanio, “If you do love me, you will find me out” ( 3.2.43 ), and in the moment of victory he insists that to have satisfied her father’s condition is not enough “Until confirmed, signed, ratified by you” ( 3.2.152 ). The dead father is satisfied, but theatrically the emphasis falls on the satisfaction of the living daughter.

In the story of Shylock and Jessica all these emphases are reversed. Jessica’s loyalties are divided. She recognizes a real obligation to her father—“Alack, what heinous sin is it in me / To be ashamed to be my father’s child?” ( 2.3.16 –17)—and she hopes her elopement will “end this strife” ( 2.3.20 ). For her it does (with reservations we will come to later); but Shakespeare puts the focus on the pain and humiliation it causes Shylock. The vicious taunts he endures from the Venetians identify him as an old man who has lost his potency, “two stones, two rich and precious stones” ( 2.8.20 –21), and his cry, “My own flesh and blood to rebel!” draws Solanio’s cruel retort, “Out upon it, old carrion! Rebels it at these years?” ( 3.1.34 –36). While Portia’s father retains his power beyond the grave, Shylock is mocked as an impotent old man. We may find Lancelet Gobbo’s teasing of his blind father cruel; while Shakespeare’s contemporaries had stronger stomachs for this sort of thing than we do, Shakespeare’s own humor is not usually so heartless. With the taunting of Shylock he goes further: the jokes of Salarino and Solanio, like those of Iago, leave us feeling no impulse to laugh.

This brings us to the problem of the way comedy treats outsiders, and to the cruelty that so often lies at the heart of laughter. Portia begins her dissection of her unwanted suitors “I know it is a sin to be a mocker, but . . .” ( 1.2.57 –58) and goes on to indulge that sin with real gusto. The unwanted suitors are all foreigners, and are mocked as such; only the Englishman, we notice, gets off lightly. (His fault, interestingly, is his inability to speak foreign languages; in one of the play’s more complicated jokes, the insularity of the English audience, which the rest of the scene plays up to, becomes itself the target of laughter.) Morocco and Arragon lose the casket game for good reasons. Morocco chooses the gold casket because he thinks the phrase “what many men desire” is a sign of Portia’s market value. This is a tribute, but not the tribute of love. Arragon thinks not of Portia’s worth but of his own. Besides, Morocco and Arragon are foreign princes, and Morocco’s foreignness is compounded by his dark skin, which Shakespeare emphasizes in a rare stage direction specifying the actor’s costume: “a tawny Moor all in white” ( 2.1.0 SD). Portia’s dismissal of him, “Let all of his complexion choose me so” ( 2.7.87 ), is for us an ugly moment. The prejudice that is, if not overturned, at least challenged and debated in Titus Andronicus and Othello is casually accepted here.

The most conspicuous problem, of course, is Shylock, and here we need to pause. The Merchant of Venice was written within a culture in which prejudice against Jews was pervasive and endemic. It can be argued that this goes back to the earliest days of Christianity, when the tradition began of making the Jews bear the guilt of the Crucifixion. Throughout medieval and early Renaissance Europe the prejudice bred dark fantasies: Jews were accused, for example, of conducting grotesque rituals in which they murdered Christian children and drank their blood. The story of a Jew who wants a pound of Christian flesh may have its roots in these fantasies of Jews violating Christian bodies. Shylock’s profession of usury is also bound up with his race: barred from other occupations, the Jews of Europe took to moneylending. Antonio’s disapproval of lending money at interest echoes traditional Christian teaching (Christian practice was another matter). Shylock’s boast that he makes his gold and silver breed like ewes and rams would remind his audience of the familiar argument that usury was against the law of God because metal was sterile and could not breed. Not just in his threat to Antonio, but in his day-to-day business, Shylock would appear unnatural.

Prejudice feeds on ignorance; since the Jews had been expelled from England in 1290, Shakespeare may never have met one. (There were a few in London in his time, but they could not practice their religion openly.) Given that the villainy of Shylock is one of the mainsprings of the story, it would have been far more natural for Shakespeare to exploit this prejudice than resist it. Many critics and performers, however, have insisted that he did resist it. His imagination, so the argument runs, worked on the figure of Shylock until it had created sympathy for him, seeing him as the victim of persecution. The great Victorian actor Henry Irving played him as a wronged and dignified victim, representative of a suffering race. Shylock’s famous self-defense, “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands . . .?” ( 3.1.57 –58), has been taken out of context and presented as a plea for the recognition of our common humanity. In context, however, its effect is less benevolent. Shylock’s plea is compelling and eloquent, but he himself uses it not to argue for tolerance but to defend his cruelty: “The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction” ( 3.1.70 –72). Gratiano’s taunt, “A Daniel still, say I! A second Daniel!— / I thank thee, Jew, for teaching me that word” ( 4.1.354 –55), shows that Gratiano, along with the word “Daniel,” has also picked up from Shylock, without knowing it, the word “teach,” and the echo is a terrible demonstration of the ways we teach each other hate so that prejudice moves in a vicious circle.

Does the play itself break out of this circle? There is little encouragement in the text to think so. In other plays Shakespeare casually uses the word “Jew” as a term of abuse, and this usage is intensified here. The kindest thing Lorenzo’s friends can find to say about Jessica is that she is “a gentle and no Jew” ( 2.6.53 ). We are aware of the pain Shylock feels in defeat; but the play emphasizes that he has brought it on himself, and no one in the play expresses sympathy for him, just as no one—except Shylock—ever questions Antonio’s right to spit on him. Given the latitude of interpretation, there are ways around the problem. Critics and performers alike have found sympathy for Shylock in his suffering, and have attacked the Christians’ treatment of him. But these readings are allowed rather than compelled by the text, and to a great extent they go against its surface impression.

It has to be said that many people who normally love Shakespeare find The Merchant of Venice painful. It even has power to do harm: it has provoked racial incidents in schools, and school boards have sometimes banned it. One may reply that the way to deal with a work one finds offensive is not censorship but criticism; in any case, everyone who teaches or performs the play needs to be aware of the problems it may create for their students and audiences, and to confront those problems as honestly as they can. At best, there are legitimate interpretations that control or resist the anti-Semitism in the text. At worst, it can be an object lesson showing that even a great writer can be bound by the prejudices of his time. To raise this kind of question is of course to go beyond the text as such and to make the problem of Shylock loom larger than it would have done for Shakespeare. In discussions of this kind, the objection “Why can’t we just take it as a play?” is often heard. But we cannot place Shakespeare in a sealed container. He belonged to his time, and, as the most widely studied and performed playwright in the world, he belongs to ours. He exerts great power within our culture, and we cannot take it for granted that this power is always benevolent.

To return to the text, and to explore the ramifications of the figure of Shylock a bit further: Shylock, Morocco, and Arragon are not the play’s only losers. The group, paradoxically, includes Antonio, who is the center of so much friendship and concern. In the final scene he is a loner in a world of couples, and the sadness he expressed at the beginning of the play does not really seem to have lifted. He resists attempts to make him reveal his secret; but when to Solanio’s “Why then you are in love” he replies “Fie, fie!” ( 1.1.48 ), we notice it is not a direct denial. Solanio himself later makes clear the depth of Antonio’s feeling for Bassanio: “I think he only loves the world for him” ( 2.8.52 ). In the trial scene Antonio tells Bassanio to report his sacrifice and bid Portia “be judge / Whether Bassanio had not once a love” ( 4.1.288 –89). Antonio has not only accepted Bassanio’s marriage, he has helped make it possible—yet there is a touch of rivalry here. In the trial his courageous acceptance of death shades into an actual yearning for it, and in the final restoration of his wealth there is something restrained and cryptic. Portia will not tell him how she came by the news that his ships have been recovered; his own response, “I am dumb” ( 5.1.299 ), has the same curtness as Shylock’s “I am content” ( 4.1.410 ), and the same effect of closing off conversation. Whether we should call Antonio’s love for Bassanio “homosexual” is debatable; the term did not exist until fairly recently, and some social historians argue that the concept did not exist either. Our own language of desire and love does not necessarily apply in other cultures. What matters to our understanding of the play is that Antonio’s feeling for Bassanio is not only intense but leaves him excluded from the sort of happiness the other characters find as they pair off into couples. This gives Antonio an ironic affinity with his enemy Shylock: both are outsiders. Many current productions end with Antonio conspicuously alone as the couples go off to bed.

Another character who is in low spirits at the end of some productions of The Merchant of Venice is Jessica. There is less warrant for this in the text, apart from her line “I am never merry when I hear sweet music” ( 5.1.77 ). Jessica is a significant case of a character who has broken the barrier between outsider and insider, joining a group (the Christians) to which she did not originally belong. She is welcomed, and seems at ease in her new world, but Lancelet Gobbo, the plainspoken and sometimes anarchic clown of the play, raises doubts about the efficacy of her conversion—she is damned if she is her father’s daughter, and damned if she isn’t ( 3.5.1 –25)—and about its economic consequences: “This making of Christians will raise the price of hogs” ( 3.5.22 –23). In a play in which money counts for so much, this is a very pointed joke. Lancelet uses his clown’s license to raise the question of whether Jessica will ever be fully accepted in Christian society. (His own contribution to race relations has been to get a Moor pregnant, and his reference to her does not sound affectionate.) Jessica’s uneasiness at going into male disguise could suggest a worry about the deeper change she is making in her nature.

Her uneasiness also makes a revealing contrast with Portia’s attitude to her disguise, and suggests there may be a parallel between the two women. Given her easy dominance of every scene in which she appears, it may seem odd to think of Portia as an outsider. But she is a woman in a society whose structures are male-centered and patriarchal. She greets her marriage with a surrender of herself and her property to a man who, like her father, will have full legal control over her:

Myself, and what is mine, to you and yours

Is now converted. But now I was the lord

Of this fair mansion, master of my servants,

Queen o’er myself; and even now, but now,

This house, these servants, and this same myself

Are yours, my lord’s.

( 3.2.170 –75)

Yet she continues to dominate Bassanio, and more than that: like Jessica, she uses male disguise to enter another world, the exclusive male club (as it then was) of the legal profession. Unlike Jessica, she moves into this new world with confidence. Her mockery of swaggering young men as she plans her disguise is irrelevant to the story but seems to answer a need in the character to poke fun at the sex whose rules she is about to subvert. Not for the only time in Shakespeare, we see a stage full of men who need a woman to sort out their problems.

Portia may also be seen as bringing fresh air from Belmont into the sea-level miasma of Venice, and readings of the play have often been constructed around a sharp opposition between the two locations, between the values of Portia and the values of Shylock. Shakespeare, however, will not leave it at that; there are constant echoes back and forth between the play’s apparently disparate worlds. Portia gives a ring to Bassanio, who gives it away; Leah gave a ring to Shylock, and Jessica steals it. Keys lock Shylock’s house and unlock the caskets of Belmont. Portia calls Bassanio “dear bought” ( 3.2.326 ) and Shylock uses almost the same words for his pound of flesh, which is “dearly bought” ( 4.1.101 ). Shylock’s proverb, “Fast bind, fast find” ( 2.5.55 ), could be a comment on the way the women use the rings to bind the men to them. His claim on Antonio’s body is grotesque, but the adultery jokes of the final scene remind us that married couples also claim exclusive rights in each other’s bodies. Marriage is mutual ownership, and Shylock’s recurring cry of “mine!” echoes throughout the play.

The final images of harmony are a bit precarious. The moonlight reminds Lorenzo and Jessica of stories of tragic, betrayed love, in which they teasingly include their own. These stories are stylized and distanced, but not just laughed off as the tale of Pyramus and Thisbe is in A Midsummer Night’s Dream . The problem of the rings is laughed off, but there is some pain and anxiety behind the laughter. The stars are “patens of bright gold” ( 5.1.67 )—that is, plates used in the Eucharist which are also rich material objects. The play’s materialism touches even the spiritual realm, and Lorenzo’s eloquent account of the music of the spheres ends with a reminder that “we cannot hear it” ( 5.1.73 ). When Portia describes the beauty of the night, she creates a paradox: “This night methinks is but the daylight sick; / It looks a little paler” ( 5.1.137 –38). So, as we watch the lovers go off to bed, we may think of their happiness, or of the human cost to those who have been excluded; we may wonder how much it matters that this happiness was bought in part with Shylock’s money. A brilliant night, or a sickly day? We may feel that this is another harmony whose music eludes us. Or we may conclude that the happiness is all the more precious for being hard-won, and all the more believable for the play’s acknowledgment that love is part of the traffic of the world.

Stay connected

Find out what’s on, read our latest stories, and learn how you can get involved.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- How did Shakespeare die?

- Why is Shakespeare still important today?

The Merchant of Venice

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Shakespeare Birthplace Trust - The Merchant of Venice - Synopsis and Plot Overview

- Utah Shakespeare Festival - The Merchant of Venice

- Folgar Shakespeare Library - "The Merchant of Venice"

- Internet Archive - "The merchant of Venice"

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology - The Merchant of Venice

- Lit2Go - "The Merchant of Venice"

- PlayShakespeare.com - The Merchant of Venice Overview: Sources & Statistics

- The Merchant of Venice - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

The Merchant of Venice , comedy in five acts by William Shakespeare , written about 1596–97 and printed in a quarto edition in 1600 from an authorial manuscript or copy of one.

Bassanio, a noble but penniless Venetian, asks his wealthy merchant friend Antonio for a loan so that Bassanio can undertake a journey to woo the heiress Portia . Antonio, whose money is invested in foreign ventures, borrows the sum from Shylock , a Jewish moneylender, on the condition that, if the loan cannot be repaid in time, Antonio will forfeit a pound of flesh. Antonio is reluctant to do business with Shylock, whom he despises for lending money at interest (unlike Antonio himself, who provides the money for Bassanio without any such financial obligation); Antonio considers that lending at interest violates the very spirit of Christianity. Nevertheless, he needs help in order to be able to assist Bassanio. Meanwhile, Bassanio has met the terms of Portia’s father’s will by selecting from three caskets the one that contains her portrait, and he and Portia marry. (Two previous wooers, the princes of Morocco and Aragon, have failed the casket test by choosing what many men desire or what the chooser thinks he deserves; Bassanio knows that he must paradoxically “give and hazard all he hath” to win the lady.) News arrives that Antonio’s ships have been lost at sea. Unable to collect on his loan, Shylock attempts to use justice to enforce a terrible, murderous revenge on Antonio: he demands his pound of flesh. Part of Shylock’s desire for vengeance is motivated by the way in which the Christians of the play have banded together to enable his daughter Jessica to elope from his house, taking with her a substantial portion of his wealth, in order to become the bride of the Christian Lorenzo. Shylock’s revengeful plan is foiled by Portia, disguised as a lawyer, who turns the tables on Shylock by a legal quibble: he must take flesh only, and Shylock must die if any blood is spilled. Thus, the contract is canceled, and Shylock is ordered to give half of his estate to Antonio, who agrees not to take the money if Shylock converts to Christianity and restores his disinherited daughter to his will. Shylock has little choice but to agree. The play ends with the news that, in fact, some of Antonio’s ships have arrived safely.

The character of Shylock has been the subject of modern scholarly debate over whether the playwright displays anti-Semitism or religious tolerance in his characterization, for, despite his stereotypical usurious nature, Shylock is depicted as understandably full of hate, having been both verbally and physically abused by Christians, and he is given one of Shakespeare’s most eloquent speeches (“Hath not a Jew eyes?…”).

For a discussion of this play within the context of Shakespeare’s entire corpus, see William Shakespeare: Shakespeare’s plays and poems .

Experience the Joy of Learning

- Just Great DataBase

Religion in The Merchant of Venice Essay

Religion was a major factor in a number of Shakespeare’s plays. Religion motivated action and reasoning. In Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,” religion was more than a belief in a higher being; it reflected moral standards and ways of living. In the “Merchant of Venice,” “a Christian ethic of generosity, love, and risk-taking friendship is set in pointed contrast with a non-Christian ethic that is seen, from a Christian point of view, as grudging, resentful, and self-calculating.” (Bevington, pg. 74) Although Shakespeare writes this drama from a Christian point of view he illustrates religion by conflicts of the Old Testament and the New Testament in Venetian society and its court of law. These Testaments are tested through the Christians and Jews of Venice.

Venice, where this drama takes place, is a largely religious Italian City. Although filled with spiritual people, the city is divided into two different religious groups. Venice was primarily and dominantly a Christian society with Jews as it’s unfairly treated minority. Stereotypes classified Jews as immoral, evil, and foolish people while the Christians were graceful, merciful, and loving. Representing the Christian belief is Antonio who is summoned to court by a Jew who goes by the name Shylock. The cross between Christianity and Judaism begins as Antonio and Shylock create a legally binding bond. The bond’s fine print expresses that if Antonio cannot fulfill his debt to Shylock, Shylock will receive a pound of Antonio’s flesh. As learned in the play, Antonio cannot repay his debt and Shylock publically exclaims his need to receive fulfillment of that bond. Hastily, Shylock is determined to obtain his pound of Christian flesh. Shakespeare provides his audience distinct differences between Antonio and Shylock. The contrast between Antonio and Shylock are comparable and somewhat parallel to the New Testament that Christians practice and to the Old Testament that Shylock adheres to.

First, we see Antonio, a soft-hearted and morose Christian gentleman whose riches cannot provide him the fulfillment that others deem appropriate. He is sad because he lacks love. To fulfill that love, he assists Bassano in his own quest to pursue love. Though usually depicted as a homosexual relationship, it is a portrayal of love between friends or brothers, another type of bond. This act of bonding puts Antonio in gracious light. He helps his loved one by borrowing money from Shylock and pawns his life to strengthen that bond. This reinforced bondage reflects Antonio’s selflessness, God-like quality, and most importantly Christian morality.

Shylock on the other hand is not put on the same pedestal as Antonio. As the Jewish representation of Venice, Shylock, “as a usurer, refuses to lend money interest-free in the name of friendship.” (Bevington, pg. 76) This act of usury in the eyes of Christianity is considered sinful, immoral and inhumane. Instead of lending money interest-free he applies collateral and conditions to the bond. Also, Christians of the time looked at Jews with negativity. “It can be argued that this goes back to the earliest days of Christianity, when the tradition began of making the Jews bear the guilt of the Crucifixion. Throughout medieval and early Renaissance Europe the prejudice bred dark fantasies: Jews were accused, for example, of conducting grotesque rituals in which they murdered Christian children and drank their blood. The story of a Jew who wants a pound of Christian flesh may have its roots in these fantasies of Jews violating Christian bodies.” (Mowat, pg. 214-215) All Jews were blamed for Christ’s death. Shylock who had nothing to do with Christ’s death still had to suffer Christian stereotypes and discrimination. He was looked at by Christians as a violent and corrupt individual. Unfortunately, the manner which he seeks Antonio’s flesh seems similar to the “grotesque rituals in which Jews murdered Christian children.” With Shakespeare thickly drawing the line between Christianity and Judaism we can ultimately assume that the bond between Shylock and Antonio, a Christian and a Jew, can only cause a great deal of controversy.

The court scene where Shylock goes to complete the sentence of his bond is where he will be introduced to the conflict of justice and mercy. More importantly we the audience also sees the New versus the Old testament put in similar contrast with Christianity and Judaism. Shylock is representative of the Old Testament. He represents law and justice. “He rigidly adheres to his “bond”, in strict accordance with the Mosaic principle of “an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.” (Swisher, pg. 70) Shylock goes forth to all extent, refusing double the amount of ducats owed to him as long as he has his bond. Shylock strictly follows the Old Testament of law and is determined to receive justice. Portia on the other hand teaches the audience the practice of the New Testament. The New Testament which embodies grace, mercy, and forgiveness

In Act Four, Scene 1, the Duke says, “We all expect a gentle answer, Jew.” (Bevington, pg. 102) This passage from the Duke pleas Shylock for a “gentle” answer. The Duke asking for a “gentle” answer was not a way to dismiss Shylock’s bond, but it was merely asking Shylock to bring forth his mercy and forgiveness as a Christian would. Thus doing so will spare Antonio’s life. According to the Essays in Shakespearean Criticism, “ “Gentle” in all its tricky ambiguity: as meaning something purely external (well-born; Christian) as well as kind, generous, loving…. “we have good reason to suppose that the language of Shakespeare’s source begged the question of gentility; we know that it begged the question of Christianity.” (Calderwood, pg. 252-253) Here Shakespeare questions Shylock’s Christian morality and his ability to practice the New Testament.

Act four-scene one, is another area in which Christianity as well as the New Testament is applied. Portia says,

“ The quality of mercy is not strained, It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven Upon the place beneath. It is twice blessed: It blesseth him that gives, and him that takes. ‘Tis mightiest in the mightiest, it becomes The throned monarch better than his crown: His scepter shows the force of temporal power, The attribute to awe and majesty, Wherin doth sit the dread and fear of kinds: But mercy is above this sceptred sway, It is enthroned in the hearts of kinds, It is an attribute to God himself: And earthly power doth then show likest God’s When mercy seasons justice. “ (4.1.182-195)

As Antonio confesses the bond, Portia is stating that Shylock “must be merciful” which greatly represents practice of the New Testament. This powerful line suggests those who give mercy will receive mercy. God gives mercy and those who can wholeheartedly give mercy is God-like. Perhaps, Portia here also tries to provide mercy onto Shylock himself. Portia knows that Shylock demands every aspect of his bond but she tries to plea with him anyway. This passage and the passage from the Duke is asking for Shylock although a Jew, to act Christian. Again, Shakespeare highlights acts of the New Testament.

Regardless of these pleas, Shylock demands a pound of Antonio’s flesh and God ruling vicariously through Portia allows Shylock to proceed with his rightful bond. Justice with his bond. However, this back fires on him. Shylock while attempting to cut off a pound of Antonio’s flesh is reminded by Portia of conditions that he has missed. The bond does say he can have a pound of flesh, however a pound it has to be exact. It also does not imply Antonio shed a drop of blood. Here Shylock is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Since Shylock has gone forth with his bond, it is by Venetian law “if it be proved against an alien that by direct or indirect attempts he seek the life of any citizen, the party ‘gainst the which he doth contrive shall seize one half his goods; the other half comes to the privy coffer of the state, and the offender’s life lies in the mercy of the duke only, ‘gainst all other voice” (4.1.347-354) In this case a Jew, who has attempted murder onto a citizen shall be tried himself. In the eyes of God, murder is a sin and therefore Shylock is in turn to be justified just as much as he sought his own justice.

Concluding the court scene, Venetian law requires Shylock to give up half of his property to the state, the other to Antonio, and give up his life. However, Antonio interjects and bargains that Shylock should live if he turn a Christian. “This was a punishment from Shylock’s point of view, … but from Antonio’s point of view, it also gave to Shylock a chance of eternal joy.” Antonio here believes Shylock can be saved. Assuming Shylock should turn Christian, this image hints conversion from the Old to the New Testament. Thus, Shylock’s “Jewish heart” who’s hunger for justice resulted in his own justification, will be introduced to mercy and he shall see salvation.

According to the “Harmonies of the Merchant of Venice”, “the essential thing added to the law by Christ is forgiveness. Mercy, therefore, is made part of the law, rather than an opposing principle. Indeed mercy, or forgiveness, becomes the legal principle enabling all other legal principles.” (Danson, pg. 65) In this case, Shylock was overturned by this Christian government for his lack of mercy or forgiveness. Christians believed in mercy while Shylock only sought justice. For Shylock, his justice seeking could not enable him to provide the mercy asked by God and thus was eventually lead to his own demise. Antonio however, showed how “Christian” he is. Although he asks Shylock to convert, he provides Shylock and opportunity. Instead of taking his life, Antonio is seen through Elizabethan eyes to have given Shylock mercy, forgiveness, and a chance to live.

Lastly, Shylock’s daughter Jessica is another representation of conversion from the Old to the New Testament. Jessica also a Jew, escapes from home and marries Lorenzo, a Christian. Ironically, she as well breaks a bond with Shylock. This bond would be a father-daughter bond. According to Jessica, “I shall be saved by my husband. He hath made me a Christian.” (3.5.17-18) Jessica being “saved” by her husband can be compared to Shylock’s conversion to Christianity. “Jessica, as the “daughter of Jerusalem” under the Old Law, then as the bride of Christ under the New” (Swisher, pg. 71)

In conclusion, we can see how powerfully influential religion was in “The Merchant of Venice.” Love, forgiveness, and most importantly mercy, represented the New Testament whilst justice, lack of mercy, and adherence to the law represented the Old Testament. These opposing values were reflected by the Jews and Christians of Venice which Shylock, Antonio, Portia, and Jessica embodied throughout the play. It is the court scene where we are confronted with Christian values and how it played a significant role in Venetian courts and most importantly in Shylock’s fate. Shylock’s need for justice and strict adherence to the law parallels the Old Testament greatly and in a Christian point of view, it was at his disadvantage. Shylock and Jessica’s conversion to Christianity or the New Testament of love, mercy, and grace, indicate the power Christianity had in law and in love. Ultimately, it is safe to say that religion in Venice took the role of judge, and that is, Christ, as its supreme judge.

Works Cited:

Bevington, David. The Necessary Shakespeare. 3. Longman Publishing Group , 2008. Print. Calderwood, James L. Essays in Shakespearean Criticism. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, INC., 1970. Print. Danson, Lawrence. The Harmonies of The Merchant of Venice. Great Britain: Yale University Press, 1978. Print. Mowat, Barbara A., and Paul Werstine. The Merchant of Venice. New York: Washington Square Press, 1992. Print. Swisher, Clarice. The Literary Companion Series: The Merchant of Venice. 1. San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 1999. Print.

Author: Angel Bell

COMMENTS

The Merchant of Venice plays as part of our Winter 2021/22 season in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse from until 9 April 2022. Globe scholars will be joined by theatre artists and scholars to discuss race and social justice in The Merchant of Venice as part of our series of free online Anti-Racist Shakespeare webinars, on 15 March 2022, 6.00pm.

Religion was a major factor in a number of Shakespeare's plays. Religion motivated action and reasoning. In Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice," religion was more than a belief in a higher being; it reflected moral standards and ways of living. In the "Merchant of Venice," "a Christian ethic of generosity, love, and risk-taking ...

in The Merchant of Venice, what one might call its ambiguity of genre, the way the play oscillates between tragedy and comedy. II The most thoroughgoing attempt I have seen to characterize Shylock and Antonio as products of their religious principles is Allan Bloom's essay, "Christian and Jew: The Merchant of Ven-ice." Bloom describes Shylock ...

"A Note on the Sources of The Merchant of Venice." Shakespeare 142-144. Sewell, Arthur. Character and Society in Shakespeare. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951. Shakespeare, William. The Merchant ...

The Merchant of Venice is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598.A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan taken out on behalf of his dear friend, Bassanio, and provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock, with seemingly inevitable fatal consequences.. Although classified as a comedy in the First Folio and sharing certain aspects with ...

By Alexander Leggatt. The Merchant of Venice is a comedy. Comedies traditionally end in marriage, and on the way they examine the social networks in which marriage is involved: the relations among families, among friends, among parents and children, and what in Shakespeare's society were the all-important ties of money and property.

The main themes in The Merchant of Venice are mercy versus justice, interpretation, and prejudice and anti-Semitism. Mercy versus justice: The principles of mercy and justice are shown to be at ...

For Harold Bloom, in a persuasive analysis of The Merchant of Venice in his book Shakespeare: The Invention Of The Human, The Merchant of Venice presents a number of difficult problems. First, there's no denying it is an anti-Semitic play; second, for Bloom, Shylock should be played as a comic villain and not a sympathetic character for the ...

Human and Animal. Themes and Colors. LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in The Merchant of Venice, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work. The Venetians in The Merchant of Venice almost uniformly express extreme intolerance of Shylock and the other Jews in Venice. In fact, the exclusion of these "others" seems ...

The Merchant of Venice, comedy in five acts by William Shakespeare, written about 1596-97 and printed in a quarto edition in 1600 from an authorial manuscript or copy of one.. Bassanio, a noble but penniless Venetian, asks his wealthy merchant friend Antonio for a loan so that Bassanio can undertake a journey to woo the heiress Portia.Antonio, whose money is invested in foreign ventures ...

Religion was a major factor in a number of Shakespeare's plays. Religion motivated action and reasoning. In Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice," religion was more than a belief in a higher being; it reflected moral standards and ways of living. In the "Merchant of Venice," "a Christian ethic of generosity, love, and risk-taking ...

A children's novel by Mirjam Pressler, Tochter (1999), translated as Shylock's Daughter (2000), retells Jessica's story from a post-Holocaust perspective of anti-Semitism and assimilation. Michael Scrivener, in his book on the figure of the "Jew" in nineteenth-century British culture, follows Janet Adelman in a revisionist reading of ...

Antonio, a merchant of Venice, loans his bankrupt friend Bassanio money to woo Portia, the heiress of Belmont. To get the money, Antonio himself has to borrow it from Shylock, a usurious Jew who ...

Master Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice using Absolute Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice essay, plot summary, quotes and characters study guides. Plot Summary: A quick plot review of The Merchant of Venice including every important action in the play. An ideal introduction before reading the original text. Commentary: Detailed description of ...

Below you will find the important quotes in The Merchant of Venice related to the theme of Law, Mercy, and Revenge. Act 1, scene 3 Quotes. I will buy with you, sell with you, talk with you, walk with you, and so following; but I will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with you. Related Characters: Shylock (speaker), Bassanio.

Plot Summary of The Merchant of Venice. The Merchant of Venice follows Bassanio, who is too poor to attempt to win the hand of his true love, Portia. In order to travel to Portia's estate, he asks his best friend, Antonio, for a loan. Because Antonio's money is invested in a number of trade ships, the two friends ask to borrow money from ...

Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "The Merchant of Venice" by William Shakespeare. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Topic #1. Much of the plot of The Merchant of Venice is generated by contractual obligations. These take the form of legally binding contracts, such as the bond between Antonio and Shylock, as ...

The Merchant of Venice is a play written in the 1590s by the English playwright William Shakespeare. It concerns a Jewish moneylender in Venice named Shylock who is determined to extract a pound of flesh from a merchant who fails to pay a debt on time. The play remains controversial due to the anti-Semitic stereotypes it perpetuated in its time and for centuries thereafter.

Shakespeare's late romance, The Tempest (1510-1) takes the form of a "revenge tragedy averted," beginning with the revenge plot but ending happily. Merchant of Venice might be described as a revenge tragedy barely averted, as Portia swoops into the courtroom scene and saves Antonio from Shylock.