Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on May 9, 2024.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

| Voluntary participation | Your participants are free to opt in or out of the study at any point in time. |

|---|---|

| Informed consent | Participants know the purpose, benefits, risks, and funding behind the study before they agree or decline to join. |

| Anonymity | You don’t know the identities of the participants. Personally identifiable data is not collected. |

| Confidentiality | You know who the participants are but you keep that information hidden from everyone else. You anonymize personally identifiable data so that it can’t be linked to other data by anyone else. |

| Potential for harm | Physical, social, psychological and all other types of harm are kept to an absolute minimum. |

| Results communication | You ensure your work is free of or research misconduct, and you accurately represent your results. |

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, May 09). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, what is your plagiarism score.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Your environment. your health., what is ethics in research & why is it important, by david b. resnik, j.d., ph.d..

December 23, 2020

The ideas and opinions expressed in this essay are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of the NIH, NIEHS, or US government.

When most people think of ethics (or morals), they think of rules for distinguishing between right and wrong, such as the Golden Rule ("Do unto others as you would have them do unto you"), a code of professional conduct like the Hippocratic Oath ("First of all, do no harm"), a religious creed like the Ten Commandments ("Thou Shalt not kill..."), or a wise aphorisms like the sayings of Confucius. This is the most common way of defining "ethics": norms for conduct that distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable behavior.

Most people learn ethical norms at home, at school, in church, or in other social settings. Although most people acquire their sense of right and wrong during childhood, moral development occurs throughout life and human beings pass through different stages of growth as they mature. Ethical norms are so ubiquitous that one might be tempted to regard them as simple commonsense. On the other hand, if morality were nothing more than commonsense, then why are there so many ethical disputes and issues in our society?

Alternatives to Animal Testing

Alternative test methods are methods that replace, reduce, or refine animal use in research and testing

Learn more about Environmental science Basics

One plausible explanation of these disagreements is that all people recognize some common ethical norms but interpret, apply, and balance them in different ways in light of their own values and life experiences. For example, two people could agree that murder is wrong but disagree about the morality of abortion because they have different understandings of what it means to be a human being.

Most societies also have legal rules that govern behavior, but ethical norms tend to be broader and more informal than laws. Although most societies use laws to enforce widely accepted moral standards and ethical and legal rules use similar concepts, ethics and law are not the same. An action may be legal but unethical or illegal but ethical. We can also use ethical concepts and principles to criticize, evaluate, propose, or interpret laws. Indeed, in the last century, many social reformers have urged citizens to disobey laws they regarded as immoral or unjust laws. Peaceful civil disobedience is an ethical way of protesting laws or expressing political viewpoints.

Another way of defining 'ethics' focuses on the disciplines that study standards of conduct, such as philosophy, theology, law, psychology, or sociology. For example, a "medical ethicist" is someone who studies ethical standards in medicine. One may also define ethics as a method, procedure, or perspective for deciding how to act and for analyzing complex problems and issues. For instance, in considering a complex issue like global warming , one may take an economic, ecological, political, or ethical perspective on the problem. While an economist might examine the cost and benefits of various policies related to global warming, an environmental ethicist could examine the ethical values and principles at stake.

See ethics in practice at NIEHS

Read latest updates in our monthly Global Environmental Health Newsletter

Many different disciplines, institutions , and professions have standards for behavior that suit their particular aims and goals. These standards also help members of the discipline to coordinate their actions or activities and to establish the public's trust of the discipline. For instance, ethical standards govern conduct in medicine, law, engineering, and business. Ethical norms also serve the aims or goals of research and apply to people who conduct scientific research or other scholarly or creative activities. There is even a specialized discipline, research ethics, which studies these norms. See Glossary of Commonly Used Terms in Research Ethics and Research Ethics Timeline .

There are several reasons why it is important to adhere to ethical norms in research. First, norms promote the aims of research , such as knowledge, truth, and avoidance of error. For example, prohibitions against fabricating , falsifying, or misrepresenting research data promote the truth and minimize error.

Join an NIEHS Study

See how we put research Ethics to practice.

Visit Joinastudy.niehs.nih.gov to see the various studies NIEHS perform.

Second, since research often involves a great deal of cooperation and coordination among many different people in different disciplines and institutions, ethical standards promote the values that are essential to collaborative work , such as trust, accountability, mutual respect, and fairness. For example, many ethical norms in research, such as guidelines for authorship , copyright and patenting policies , data sharing policies, and confidentiality rules in peer review, are designed to protect intellectual property interests while encouraging collaboration. Most researchers want to receive credit for their contributions and do not want to have their ideas stolen or disclosed prematurely.

Third, many of the ethical norms help to ensure that researchers can be held accountable to the public . For instance, federal policies on research misconduct, conflicts of interest, the human subjects protections, and animal care and use are necessary in order to make sure that researchers who are funded by public money can be held accountable to the public.

Fourth, ethical norms in research also help to build public support for research. People are more likely to fund a research project if they can trust the quality and integrity of research.

Finally, many of the norms of research promote a variety of other important moral and social values , such as social responsibility, human rights, animal welfare, compliance with the law, and public health and safety. Ethical lapses in research can significantly harm human and animal subjects, students, and the public. For example, a researcher who fabricates data in a clinical trial may harm or even kill patients, and a researcher who fails to abide by regulations and guidelines relating to radiation or biological safety may jeopardize his health and safety or the health and safety of staff and students.

Codes and Policies for Research Ethics

Given the importance of ethics for the conduct of research, it should come as no surprise that many different professional associations, government agencies, and universities have adopted specific codes, rules, and policies relating to research ethics. Many government agencies have ethics rules for funded researchers.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Singapore Statement on Research Integrity

- American Chemical Society, The Chemist Professional’s Code of Conduct

- Code of Ethics (American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science)

- American Psychological Association, Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

- Statement on Professional Ethics (American Association of University Professors)

- Nuremberg Code

- World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki

Ethical Principles

The following is a rough and general summary of some ethical principles that various codes address*:

Strive for honesty in all scientific communications. Honestly report data, results, methods and procedures, and publication status. Do not fabricate, falsify, or misrepresent data. Do not deceive colleagues, research sponsors, or the public.

Objectivity

Strive to avoid bias in experimental design, data analysis, data interpretation, peer review, personnel decisions, grant writing, expert testimony, and other aspects of research where objectivity is expected or required. Avoid or minimize bias or self-deception. Disclose personal or financial interests that may affect research.

Keep your promises and agreements; act with sincerity; strive for consistency of thought and action.

Carefulness

Avoid careless errors and negligence; carefully and critically examine your own work and the work of your peers. Keep good records of research activities, such as data collection, research design, and correspondence with agencies or journals.

Share data, results, ideas, tools, resources. Be open to criticism and new ideas.

Transparency

Disclose methods, materials, assumptions, analyses, and other information needed to evaluate your research.

Accountability

Take responsibility for your part in research and be prepared to give an account (i.e. an explanation or justification) of what you did on a research project and why.

Intellectual Property

Honor patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. Do not use unpublished data, methods, or results without permission. Give proper acknowledgement or credit for all contributions to research. Never plagiarize.

Confidentiality

Protect confidential communications, such as papers or grants submitted for publication, personnel records, trade or military secrets, and patient records.

Responsible Publication

Publish in order to advance research and scholarship, not to advance just your own career. Avoid wasteful and duplicative publication.

Responsible Mentoring

Help to educate, mentor, and advise students. Promote their welfare and allow them to make their own decisions.

Respect for Colleagues

Respect your colleagues and treat them fairly.

Social Responsibility

Strive to promote social good and prevent or mitigate social harms through research, public education, and advocacy.

Non-Discrimination

Avoid discrimination against colleagues or students on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, or other factors not related to scientific competence and integrity.

Maintain and improve your own professional competence and expertise through lifelong education and learning; take steps to promote competence in science as a whole.

Know and obey relevant laws and institutional and governmental policies.

Animal Care

Show proper respect and care for animals when using them in research. Do not conduct unnecessary or poorly designed animal experiments.

Human Subjects protection

When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy; take special precautions with vulnerable populations; and strive to distribute the benefits and burdens of research fairly.

* Adapted from Shamoo A and Resnik D. 2015. Responsible Conduct of Research, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press).

Ethical Decision Making in Research

Although codes, policies, and principles are very important and useful, like any set of rules, they do not cover every situation, they often conflict, and they require interpretation. It is therefore important for researchers to learn how to interpret, assess, and apply various research rules and how to make decisions and act ethically in various situations. The vast majority of decisions involve the straightforward application of ethical rules. For example, consider the following case:

The research protocol for a study of a drug on hypertension requires the administration of the drug at different doses to 50 laboratory mice, with chemical and behavioral tests to determine toxic effects. Tom has almost finished the experiment for Dr. Q. He has only 5 mice left to test. However, he really wants to finish his work in time to go to Florida on spring break with his friends, who are leaving tonight. He has injected the drug in all 50 mice but has not completed all of the tests. He therefore decides to extrapolate from the 45 completed results to produce the 5 additional results.

Many different research ethics policies would hold that Tom has acted unethically by fabricating data. If this study were sponsored by a federal agency, such as the NIH, his actions would constitute a form of research misconduct , which the government defines as "fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism" (or FFP). Actions that nearly all researchers classify as unethical are viewed as misconduct. It is important to remember, however, that misconduct occurs only when researchers intend to deceive : honest errors related to sloppiness, poor record keeping, miscalculations, bias, self-deception, and even negligence do not constitute misconduct. Also, reasonable disagreements about research methods, procedures, and interpretations do not constitute research misconduct. Consider the following case:

Dr. T has just discovered a mathematical error in his paper that has been accepted for publication in a journal. The error does not affect the overall results of his research, but it is potentially misleading. The journal has just gone to press, so it is too late to catch the error before it appears in print. In order to avoid embarrassment, Dr. T decides to ignore the error.

Dr. T's error is not misconduct nor is his decision to take no action to correct the error. Most researchers, as well as many different policies and codes would say that Dr. T should tell the journal (and any coauthors) about the error and consider publishing a correction or errata. Failing to publish a correction would be unethical because it would violate norms relating to honesty and objectivity in research.

There are many other activities that the government does not define as "misconduct" but which are still regarded by most researchers as unethical. These are sometimes referred to as " other deviations " from acceptable research practices and include:

- Publishing the same paper in two different journals without telling the editors

- Submitting the same paper to different journals without telling the editors

- Not informing a collaborator of your intent to file a patent in order to make sure that you are the sole inventor

- Including a colleague as an author on a paper in return for a favor even though the colleague did not make a serious contribution to the paper

- Discussing with your colleagues confidential data from a paper that you are reviewing for a journal

- Using data, ideas, or methods you learn about while reviewing a grant or a papers without permission

- Trimming outliers from a data set without discussing your reasons in paper

- Using an inappropriate statistical technique in order to enhance the significance of your research

- Bypassing the peer review process and announcing your results through a press conference without giving peers adequate information to review your work

- Conducting a review of the literature that fails to acknowledge the contributions of other people in the field or relevant prior work

- Stretching the truth on a grant application in order to convince reviewers that your project will make a significant contribution to the field

- Stretching the truth on a job application or curriculum vita

- Giving the same research project to two graduate students in order to see who can do it the fastest

- Overworking, neglecting, or exploiting graduate or post-doctoral students

- Failing to keep good research records

- Failing to maintain research data for a reasonable period of time

- Making derogatory comments and personal attacks in your review of author's submission

- Promising a student a better grade for sexual favors

- Using a racist epithet in the laboratory

- Making significant deviations from the research protocol approved by your institution's Animal Care and Use Committee or Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research without telling the committee or the board

- Not reporting an adverse event in a human research experiment

- Wasting animals in research

- Exposing students and staff to biological risks in violation of your institution's biosafety rules

- Sabotaging someone's work

- Stealing supplies, books, or data

- Rigging an experiment so you know how it will turn out

- Making unauthorized copies of data, papers, or computer programs

- Owning over $10,000 in stock in a company that sponsors your research and not disclosing this financial interest

- Deliberately overestimating the clinical significance of a new drug in order to obtain economic benefits

These actions would be regarded as unethical by most scientists and some might even be illegal in some cases. Most of these would also violate different professional ethics codes or institutional policies. However, they do not fall into the narrow category of actions that the government classifies as research misconduct. Indeed, there has been considerable debate about the definition of "research misconduct" and many researchers and policy makers are not satisfied with the government's narrow definition that focuses on FFP. However, given the huge list of potential offenses that might fall into the category "other serious deviations," and the practical problems with defining and policing these other deviations, it is understandable why government officials have chosen to limit their focus.

Finally, situations frequently arise in research in which different people disagree about the proper course of action and there is no broad consensus about what should be done. In these situations, there may be good arguments on both sides of the issue and different ethical principles may conflict. These situations create difficult decisions for research known as ethical or moral dilemmas . Consider the following case:

Dr. Wexford is the principal investigator of a large, epidemiological study on the health of 10,000 agricultural workers. She has an impressive dataset that includes information on demographics, environmental exposures, diet, genetics, and various disease outcomes such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and ALS. She has just published a paper on the relationship between pesticide exposure and PD in a prestigious journal. She is planning to publish many other papers from her dataset. She receives a request from another research team that wants access to her complete dataset. They are interested in examining the relationship between pesticide exposures and skin cancer. Dr. Wexford was planning to conduct a study on this topic.

Dr. Wexford faces a difficult choice. On the one hand, the ethical norm of openness obliges her to share data with the other research team. Her funding agency may also have rules that obligate her to share data. On the other hand, if she shares data with the other team, they may publish results that she was planning to publish, thus depriving her (and her team) of recognition and priority. It seems that there are good arguments on both sides of this issue and Dr. Wexford needs to take some time to think about what she should do. One possible option is to share data, provided that the investigators sign a data use agreement. The agreement could define allowable uses of the data, publication plans, authorship, etc. Another option would be to offer to collaborate with the researchers.

The following are some step that researchers, such as Dr. Wexford, can take to deal with ethical dilemmas in research:

What is the problem or issue?

It is always important to get a clear statement of the problem. In this case, the issue is whether to share information with the other research team.

What is the relevant information?

Many bad decisions are made as a result of poor information. To know what to do, Dr. Wexford needs to have more information concerning such matters as university or funding agency or journal policies that may apply to this situation, the team's intellectual property interests, the possibility of negotiating some kind of agreement with the other team, whether the other team also has some information it is willing to share, the impact of the potential publications, etc.

What are the different options?

People may fail to see different options due to a limited imagination, bias, ignorance, or fear. In this case, there may be other choices besides 'share' or 'don't share,' such as 'negotiate an agreement' or 'offer to collaborate with the researchers.'

How do ethical codes or policies as well as legal rules apply to these different options?

The university or funding agency may have policies on data management that apply to this case. Broader ethical rules, such as openness and respect for credit and intellectual property, may also apply to this case. Laws relating to intellectual property may be relevant.

Are there any people who can offer ethical advice?

It may be useful to seek advice from a colleague, a senior researcher, your department chair, an ethics or compliance officer, or anyone else you can trust. In the case, Dr. Wexford might want to talk to her supervisor and research team before making a decision.

After considering these questions, a person facing an ethical dilemma may decide to ask more questions, gather more information, explore different options, or consider other ethical rules. However, at some point he or she will have to make a decision and then take action. Ideally, a person who makes a decision in an ethical dilemma should be able to justify his or her decision to himself or herself, as well as colleagues, administrators, and other people who might be affected by the decision. He or she should be able to articulate reasons for his or her conduct and should consider the following questions in order to explain how he or she arrived at his or her decision:

- Which choice will probably have the best overall consequences for science and society?

- Which choice could stand up to further publicity and scrutiny?

- Which choice could you not live with?

- Think of the wisest person you know. What would he or she do in this situation?

- Which choice would be the most just, fair, or responsible?

After considering all of these questions, one still might find it difficult to decide what to do. If this is the case, then it may be appropriate to consider others ways of making the decision, such as going with a gut feeling or intuition, seeking guidance through prayer or meditation, or even flipping a coin. Endorsing these methods in this context need not imply that ethical decisions are irrational, however. The main point is that human reasoning plays a pivotal role in ethical decision-making but there are limits to its ability to solve all ethical dilemmas in a finite amount of time.

Promoting Ethical Conduct in Science

Do U.S. research institutions meet or exceed federal mandates for instruction in responsible conduct of research? A national survey

Read about U.S. research instutuins follow federal manadates for ethics in research

Learn more about NIEHS Research

Most academic institutions in the US require undergraduate, graduate, or postgraduate students to have some education in the responsible conduct of research (RCR) . The NIH and NSF have both mandated training in research ethics for students and trainees. Many academic institutions outside of the US have also developed educational curricula in research ethics

Those of you who are taking or have taken courses in research ethics may be wondering why you are required to have education in research ethics. You may believe that you are highly ethical and know the difference between right and wrong. You would never fabricate or falsify data or plagiarize. Indeed, you also may believe that most of your colleagues are highly ethical and that there is no ethics problem in research..

If you feel this way, relax. No one is accusing you of acting unethically. Indeed, the evidence produced so far shows that misconduct is a very rare occurrence in research, although there is considerable variation among various estimates. The rate of misconduct has been estimated to be as low as 0.01% of researchers per year (based on confirmed cases of misconduct in federally funded research) to as high as 1% of researchers per year (based on self-reports of misconduct on anonymous surveys). See Shamoo and Resnik (2015), cited above.

Clearly, it would be useful to have more data on this topic, but so far there is no evidence that science has become ethically corrupt, despite some highly publicized scandals. Even if misconduct is only a rare occurrence, it can still have a tremendous impact on science and society because it can compromise the integrity of research, erode the public’s trust in science, and waste time and resources. Will education in research ethics help reduce the rate of misconduct in science? It is too early to tell. The answer to this question depends, in part, on how one understands the causes of misconduct. There are two main theories about why researchers commit misconduct. According to the "bad apple" theory, most scientists are highly ethical. Only researchers who are morally corrupt, economically desperate, or psychologically disturbed commit misconduct. Moreover, only a fool would commit misconduct because science's peer review system and self-correcting mechanisms will eventually catch those who try to cheat the system. In any case, a course in research ethics will have little impact on "bad apples," one might argue.

According to the "stressful" or "imperfect" environment theory, misconduct occurs because various institutional pressures, incentives, and constraints encourage people to commit misconduct, such as pressures to publish or obtain grants or contracts, career ambitions, the pursuit of profit or fame, poor supervision of students and trainees, and poor oversight of researchers (see Shamoo and Resnik 2015). Moreover, defenders of the stressful environment theory point out that science's peer review system is far from perfect and that it is relatively easy to cheat the system. Erroneous or fraudulent research often enters the public record without being detected for years. Misconduct probably results from environmental and individual causes, i.e. when people who are morally weak, ignorant, or insensitive are placed in stressful or imperfect environments. In any case, a course in research ethics can be useful in helping to prevent deviations from norms even if it does not prevent misconduct. Education in research ethics is can help people get a better understanding of ethical standards, policies, and issues and improve ethical judgment and decision making. Many of the deviations that occur in research may occur because researchers simply do not know or have never thought seriously about some of the ethical norms of research. For example, some unethical authorship practices probably reflect traditions and practices that have not been questioned seriously until recently. If the director of a lab is named as an author on every paper that comes from his lab, even if he does not make a significant contribution, what could be wrong with that? That's just the way it's done, one might argue. Another example where there may be some ignorance or mistaken traditions is conflicts of interest in research. A researcher may think that a "normal" or "traditional" financial relationship, such as accepting stock or a consulting fee from a drug company that sponsors her research, raises no serious ethical issues. Or perhaps a university administrator sees no ethical problem in taking a large gift with strings attached from a pharmaceutical company. Maybe a physician thinks that it is perfectly appropriate to receive a $300 finder’s fee for referring patients into a clinical trial.

If "deviations" from ethical conduct occur in research as a result of ignorance or a failure to reflect critically on problematic traditions, then a course in research ethics may help reduce the rate of serious deviations by improving the researcher's understanding of ethics and by sensitizing him or her to the issues.

Finally, education in research ethics should be able to help researchers grapple with the ethical dilemmas they are likely to encounter by introducing them to important concepts, tools, principles, and methods that can be useful in resolving these dilemmas. Scientists must deal with a number of different controversial topics, such as human embryonic stem cell research, cloning, genetic engineering, and research involving animal or human subjects, which require ethical reflection and deliberation.

Research Ethics & Ethical Considerations

A Plain-Language Explainer With Examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | May 2024

Research ethics are one of those “ unsexy but essential ” subjects that you need to fully understand (and apply) to conquer your dissertation, thesis or research paper. In this post, we’ll unpack research ethics using plain language and loads of examples .

Overview: Research Ethics 101

- What are research ethics?

- Why should you care?

- Research ethics principles

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

- Objectivity

- Key takeaways

What (exactly) are research ethics?

At the simplest level, research ethics are a set of principles that ensure that your study is conducted responsibly, safely, and with integrity. More specifically, research ethics help protect the rights and welfare of your research participants, while also ensuring the credibility of your research findings.

Research ethics are critically important for a number of reasons:

Firstly, they’re a complete non-negotiable when it comes to getting your research proposal approved. Pretty much all universities will have a set of ethical criteria that student projects need to adhere to – and these are typically very strictly enforced. So, if your proposed study doesn’t tick the necessary ethical boxes, it won’t be approved .

Beyond the practical aspect of approval, research ethics are essential as they ensure that your study’s participants (whether human or animal) are properly protected . In turn, this fosters trust between you and your participants – as well as trust between researchers and the public more generally. As you can probably imagine, it wouldn’t be good if the general public had a negative perception of researchers!

Last but not least, research ethics help ensure that your study’s results are valid and reliable . In other words, that you measured the thing you intended to measure – and that other researchers can repeat your study. If you’re not familiar with the concepts of reliability and validity , we’ve got a straightforward explainer video covering that below.

The Core Principles

In practical terms, each university or institution will have its own ethics policy – so, what exactly constitutes “ethical research” will vary somewhat between institutions and countries. Nevertheless, there are a handful of core principles that shape ethics policies. These principles include:

Let’s unpack each of these to make them a little more tangible.

Ethics Principle 1: Respect for persons

As the name suggests, this principle is all about ensuring that your participants are treated fairly and respectfully . In practical terms, this means informed consent – in other words, participants should be fully informed about the nature of the research, as well as any potential risks. Additionally, they should be able to withdraw from the study at any time. This is especially important when you’re dealing with vulnerable populations – for example, children, the elderly or people with cognitive disabilities.

Another dimension of the “respect for persons” principle is confidentiality and data protection . In other words, your participants’ personal information should be kept strictly confidential and secure at all times. Depending on the specifics of your project, this might also involve anonymising or masking people’s identities. As mentioned earlier, the exact requirements will vary between universities, so be sure to thoroughly review your institution’s ethics policy before you start designing your project.

Need a helping hand?

Ethics Principle 2: Beneficence

This principle is a little more opaque, but in simple terms beneficence means that you, as the researcher, should aim to maximise the benefits of your work, while minimising any potential harm to your participants.

In practical terms, benefits could include advancing knowledge, improving health outcomes, or providing educational value. Conversely, potential harms could include:

- Physical harm from accidents or injuries

- Psychological harm, such as stress or embarrassment

- Social harm, such as stigmatisation or loss of reputation

- Economic harm – in other words, financial costs or lost income

Simply put, the beneficence principle means that researchers must always try to identify potential risks and take suitable measures to reduce or eliminate them.

Ethics Principle 3: Objectivity

As you can probably guess, this principle is all about attempting to minimise research bias to the greatest degree possible. In other words, you’ll need to reduce subjectivity and increase objectivity wherever possible.

In practical terms, this principle has the largest impact on the methodology of your study – specifically the data collection and data analysis aspects. For example, you’ll need to ensure that the selection of your participants (in other words, your sampling strategy ) is aligned with your research aims – and that your sample isn’t skewed in a way that supports your presuppositions.

If you’re keen to learn more about research bias and the various ways in which you could unintentionally skew your results, check out the video below.

Ethics Principle 4: Integrity

Again, no surprises here; this principle is all about producing “honest work” . It goes without saying that researchers should always conduct their work honestly and transparently, report their findings accurately, and disclose any potential conflicts of interest upfront.

This is all pretty obvious, but another aspect of the integrity principle that’s sometimes overlooked is respect for intellectual property . In practical terms, this means you need to honour any patents, copyrights, or other forms of intellectual property that you utilise while undertaking your research. Along the same vein, you shouldn’t use any unpublished data, methods, or results without explicit, written permission from the respective owner.

Linked to all of this is the broader issue of plagiarism . Needless to say, if you’re drawing on someone else’s published work, be sure to cite your sources, in the correct format. To make life easier, use a reference manager such as Mendeley or Zotero to ensure that your citations and reference list are perfectly polished.

FAQs: Research Ethics

Research ethics & ethical considertation, what is informed consent.

Informed consent simply means providing your potential participants with all necessary information about the study. This should include information regarding the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. This information allows your potential participants to make a voluntary and informed decision about whether to participate.

How should I obtain consent from non-English speaking participants?

What about animals.

When conducting research with animals, ensure you adhere to ethical guidelines for the humane treatment of animals. Again, the exact requirements here will vary between institutions, but typically include minimising pain and distress, using alternatives where possible, and obtaining approval from an animal care and use committee.

What is the role of the ERB or IRB?

An ethics review board (ERB) or institutional review board (IRB) evaluates research proposals to ensure they meet ethical standards. The board reviews study designs, consent forms, and data handling procedures, to protect participants’ welfare and rights.

How can I obtain ethical approval for my project?

This varies between universities, but you will typically need to submit a detailed research proposal to your institution’s ethics committee. This proposal should include your research objectives, methods, and how you plan to address ethical considerations like informed consent, confidentiality, and risk minimisation. You can learn more about how to write a proposal here .

How do I ensure ethical collaboration when working with colleagues?

Collaborative research should be conducted with mutual respect and clear agreements on roles, contributions, and publication credits. Open communication is key to preventing conflicts and misunderstandings. Also, be sure to check whether your university has any specific requirements with regards to collaborative efforts and division of labour.

How should I address ethical concerns relating to my funding source?

Key takeaways: research ethics 101.

Here’s a quick recap of the key points we’ve covered:

- Research ethics are a set of principles that ensure that your study is conducted responsibly.

- It’s essential that you design your study around these principles, or it simply won’t get approved.

- The four ethics principles we looked at are: respect for persons, beneficence, objectivity and integrity

As mentioned, the exact requirements will vary slightly depending on the institution and country, so be sure to thoroughly review your university’s research ethics policy before you start developing your study.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Home » Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations in research refer to the principles and guidelines that researchers must follow to ensure that their studies are conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. These considerations are designed to protect the rights, safety, and well-being of research participants, as well as the integrity and credibility of the research itself

Some of the key ethical considerations in research include:

- Informed consent: Researchers must obtain informed consent from study participants, which means they must inform participants about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Privacy and confidentiality : Researchers must ensure that participants’ privacy and confidentiality are protected. This means that personal information should be kept confidential and not shared without the participant’s consent.

- Harm reduction : Researchers must ensure that the study does not harm the participants physically or psychologically. They must take steps to minimize the risks associated with the study.

- Fairness and equity : Researchers must ensure that the study does not discriminate against any particular group or individual. They should treat all participants equally and fairly.

- Use of deception: Researchers must use deception only if it is necessary to achieve the study’s objectives. They must inform participants of the deception as soon as possible.

- Use of vulnerable populations : Researchers must be especially cautious when working with vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant women, prisoners, and individuals with cognitive or intellectual disabilities.

- Conflict of interest : Researchers must disclose any potential conflicts of interest that may affect the study’s integrity. This includes financial or personal relationships that could influence the study’s results.

- Data manipulation: Researchers must not manipulate data to support a particular hypothesis or agenda. They should report the results of the study objectively, even if the findings are not consistent with their expectations.

- Intellectual property: Researchers must respect intellectual property rights and give credit to previous studies and research.

- Cultural sensitivity : Researchers must be sensitive to the cultural norms and beliefs of the participants. They should avoid imposing their values and beliefs on the participants and should be respectful of their cultural practices.

Types of Ethical Considerations

Types of Ethical Considerations are as follows:

Research Ethics:

This includes ethical principles and guidelines that govern research involving human or animal subjects, ensuring that the research is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner.

Business Ethics :

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide business practices and decision-making, such as transparency, honesty, fairness, and social responsibility.

Medical Ethics :

This refers to ethical principles and standards that govern the practice of medicine, including the duty to protect patient autonomy, informed consent, confidentiality, and non-maleficence.

Environmental Ethics :

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with the natural world, including the obligation to protect the environment, minimize harm, and promote sustainability.

Legal Ethics

This involves ethical principles and standards that guide the conduct of legal professionals, including issues such as confidentiality, conflicts of interest, and professional competence.

Social Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with other individuals and society as a whole, including issues such as justice, fairness, and human rights.

Information Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that govern the use and dissemination of information, including issues such as privacy, accuracy, and intellectual property.

Cultural Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that govern the relationship between different cultures and communities, including issues such as respect for diversity, cultural sensitivity, and inclusivity.

Technological Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and guidelines that govern the development, use, and impact of technology, including issues such as privacy, security, and social responsibility.

Journalism Ethics

This involves ethical principles and standards that guide the practice of journalism, including issues such as accuracy, fairness, and the public interest.

Educational Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide the practice of education, including issues such as academic integrity, fairness, and respect for diversity.

Political Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide political decision-making and behavior, including issues such as accountability, transparency, and the protection of civil liberties.

Professional Ethics

This refers to ethical principles and standards that guide the conduct of professionals in various fields, including issues such as honesty, integrity, and competence.

Personal Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide individual behavior and decision-making, including issues such as personal responsibility, honesty, and respect for others.

Global Ethics

This involves ethical principles and values that guide our interactions with other nations and the global community, including issues such as human rights, environmental protection, and social justice.

Applications of Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are important in many areas of society, including medicine, business, law, and technology. Here are some specific applications of ethical considerations:

- Medical research : Ethical considerations are crucial in medical research, particularly when human subjects are involved. Researchers must ensure that their studies are conducted in a way that does not harm participants and that participants give informed consent before participating.

- Business practices: Ethical considerations are also important in business, where companies must make decisions that are socially responsible and avoid activities that are harmful to society. For example, companies must ensure that their products are safe for consumers and that they do not engage in exploitative labor practices.

- Environmental protection: Ethical considerations play a crucial role in environmental protection, as companies and governments must weigh the benefits of economic development against the potential harm to the environment. Decisions about land use, resource allocation, and pollution must be made in an ethical manner that takes into account the long-term consequences for the planet and future generations.

- Technology development : As technology continues to advance rapidly, ethical considerations become increasingly important in areas such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and genetic engineering. Developers must ensure that their creations do not harm humans or the environment and that they are developed in a way that is fair and equitable.

- Legal system : The legal system relies on ethical considerations to ensure that justice is served and that individuals are treated fairly. Lawyers and judges must abide by ethical standards to maintain the integrity of the legal system and to protect the rights of all individuals involved.

Examples of Ethical Considerations

Here are a few examples of ethical considerations in different contexts:

- In healthcare : A doctor must ensure that they provide the best possible care to their patients and avoid causing them harm. They must respect the autonomy of their patients, and obtain informed consent before administering any treatment or procedure. They must also ensure that they maintain patient confidentiality and avoid any conflicts of interest.

- In the workplace: An employer must ensure that they treat their employees fairly and with respect, provide them with a safe working environment, and pay them a fair wage. They must also avoid any discrimination based on race, gender, religion, or any other characteristic protected by law.

- In the media : Journalists must ensure that they report the news accurately and without bias. They must respect the privacy of individuals and avoid causing harm or distress. They must also be transparent about their sources and avoid any conflicts of interest.

- In research: Researchers must ensure that they conduct their studies ethically and with integrity. They must obtain informed consent from participants, protect their privacy, and avoid any harm or discomfort. They must also ensure that their findings are reported accurately and without bias.

- In personal relationships : People must ensure that they treat others with respect and kindness, and avoid causing harm or distress. They must respect the autonomy of others and avoid any actions that would be considered unethical, such as lying or cheating. They must also respect the confidentiality of others and maintain their privacy.

How to Write Ethical Considerations

When writing about research involving human subjects or animals, it is essential to include ethical considerations to ensure that the study is conducted in a manner that is morally responsible and in accordance with professional standards. Here are some steps to help you write ethical considerations:

- Describe the ethical principles: Start by explaining the ethical principles that will guide the research. These could include principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

- Discuss informed consent : Informed consent is a critical ethical consideration when conducting research. Explain how you will obtain informed consent from participants, including how you will explain the purpose of the study, potential risks and benefits, and how you will protect their privacy.

- Address confidentiality : Describe how you will protect the confidentiality of the participants’ personal information and data, including any measures you will take to ensure that the data is kept secure and confidential.

- Consider potential risks and benefits : Describe any potential risks or harms to participants that could result from the study and how you will minimize those risks. Also, discuss the potential benefits of the study, both to the participants and to society.

- Discuss the use of animals : If the research involves the use of animals, address the ethical considerations related to animal welfare. Explain how you will minimize any potential harm to the animals and ensure that they are treated ethically.

- Mention the ethical approval : Finally, it’s essential to acknowledge that the research has received ethical approval from the relevant institutional review board or ethics committee. State the name of the committee, the date of approval, and any specific conditions or requirements that were imposed.

When to Write Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations should be written whenever research involves human subjects or has the potential to impact human beings, animals, or the environment in some way. Ethical considerations are also important when research involves sensitive topics, such as mental health, sexuality, or religion.

In general, ethical considerations should be an integral part of any research project, regardless of the field or subject matter. This means that they should be considered at every stage of the research process, from the initial planning and design phase to data collection, analysis, and dissemination.

Ethical considerations should also be written in accordance with the guidelines and standards set by the relevant regulatory bodies and professional associations. These guidelines may vary depending on the discipline, so it is important to be familiar with the specific requirements of your field.

Purpose of Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are an essential aspect of many areas of life, including business, healthcare, research, and social interactions. The primary purposes of ethical considerations are:

- Protection of human rights: Ethical considerations help ensure that people’s rights are respected and protected. This includes respecting their autonomy, ensuring their privacy is respected, and ensuring that they are not subjected to harm or exploitation.

- Promoting fairness and justice: Ethical considerations help ensure that people are treated fairly and justly, without discrimination or bias. This includes ensuring that everyone has equal access to resources and opportunities, and that decisions are made based on merit rather than personal biases or prejudices.

- Promoting honesty and transparency : Ethical considerations help ensure that people are truthful and transparent in their actions and decisions. This includes being open and honest about conflicts of interest, disclosing potential risks, and communicating clearly with others.

- Maintaining public trust: Ethical considerations help maintain public trust in institutions and individuals. This is important for building and maintaining relationships with customers, patients, colleagues, and other stakeholders.

- Ensuring responsible conduct: Ethical considerations help ensure that people act responsibly and are accountable for their actions. This includes adhering to professional standards and codes of conduct, following laws and regulations, and avoiding behaviors that could harm others or damage the environment.

Advantages of Ethical Considerations

Here are some of the advantages of ethical considerations:

- Builds Trust : When individuals or organizations follow ethical considerations, it creates a sense of trust among stakeholders, including customers, clients, and employees. This trust can lead to stronger relationships and long-term loyalty.

- Reputation and Brand Image : Ethical considerations are often linked to a company’s brand image and reputation. By following ethical practices, a company can establish a positive image and reputation that can enhance its brand value.

- Avoids Legal Issues: Ethical considerations can help individuals and organizations avoid legal issues and penalties. By adhering to ethical principles, companies can reduce the risk of facing lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and fines.

- Increases Employee Retention and Motivation: Employees tend to be more satisfied and motivated when they work for an organization that values ethics. Companies that prioritize ethical considerations tend to have higher employee retention rates, leading to lower recruitment costs.

- Enhances Decision-making: Ethical considerations help individuals and organizations make better decisions. By considering the ethical implications of their actions, decision-makers can evaluate the potential consequences and choose the best course of action.

- Positive Impact on Society: Ethical considerations have a positive impact on society as a whole. By following ethical practices, companies can contribute to social and environmental causes, leading to a more sustainable and equitable society.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing...

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.3 Principles of Research Ethics

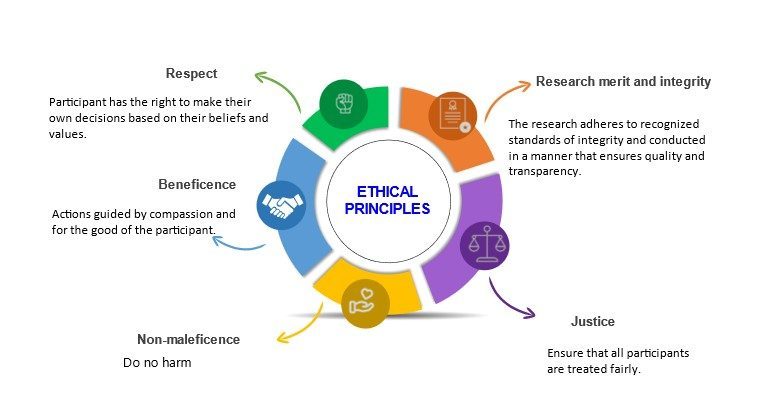

There are general ethical principles that guide and underpin the proper conduct of research. The term “ethical principles” refers to those general rules that operate as a foundational rationale for the numerous specific ethical guidelines and assessments of human behaviour. 7 The National Statement on ‘ethical conduct in human research’ states that ethical behaviour entails acting with integrity, motivated by a deep respect and concern for others. 8 Before research can be conducted, it is essential for researchers to develop and submit to a relevant human research ethics committee a research proposal that meets the National Statement’s requirements and is ethically acceptable. There are five key ethical research principles – respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice 8, 9 (Figure 6.1). These principles are universal, which means they apply everywhere in the world, without national, cultural, legal, or economic boundaries. Therefore, everyone involved in human research studies should understand and follow these principles.

Research merit and integrity

Research merit and integrity relate to the quality or value of a study in contributing to the knowledge base of a particular field or discipline. 8,9 This is determined by the originality and significance of the research question, the soundness and appropriateness of the research methodology, the rigor and reliability of the data analysis, the clarity and coherence of the research findings, and the potential impact of the research on advancing knowledge or solving practical problems. Research must be developed with methods that are appropriate to the study’s objectives, based on a thorough analysis of the relevant literature, and conducted using facilities and resources that are appropriate for the study’s needs. In essence, research must adhere to recognised standards of integrity and be designed, reviewed and conducted in a manner that ensures quality and transparency. 8 Examples of unacceptable practices include plagiarism through appropriation or use of the ideas or intellectual property of others; falsification by creating false data or other aspects of research (including documentation and consent of participants); distortion through improper manipulation and/or selection of data, images and/or consent.

Respect for persons

Respect for humans is an acknowledgement of their inherent worth, and it refers to the moral imperative to regard the autonomy of others. 8,10 Respect entails taking into account the well-being, beliefs, perspectives, practises, and cultural heritage of persons participating in research, individually and collectively. It involves respecting the participants’ privacy, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivity. 8 Respect also entails giving adequate consideration to people to make their judgements throughout the study process. In cases where the participants have limited capacity to make autonomous decisions, respect for them entails protecting them against harm. 8 This means that all participants in research must participate voluntarily without coercion or undue influence, and their rights, dignity and autonomy should be respected and adequately protected.

Beneficence

The ethical principle that requires actions that promote the well-being and interests of others is known as beneficence. 10 It is the fundamental premise underlying all medical health care and research. 8 Beneficence requires the researcher to weigh the prospective benefits and hazards and make certain that projects have the potential for net benefit over harm. 8,10 Researchers are responsible for: (a) structuring the study to minimise the risks of injury or discomfort to participants; (b) explaining the possible benefits and dangers of the research to participants; and (c) the welfare of the participants in the research setting 8. Thus, the study participants must always be prioritised over the research methodology, even if this means invalidating data. 8

Non-maleficence

This is the ethical principle that requires actions that avoid or minimize harm to others. According to the principle of non-maleficence, participating in a study shouldn’t do any harm to the research subject. This principle is closely related to beneficence; however, it may be difficult to keep track of any damage to study participants. 11 Different types of harm could occur, including physical, mental, social, or financial harm. While the physical injury may be quickly recognised and then avoided or reduced, less evident issues such as emotional, social, and economic factors might hurt the subject without the researcher being aware. 11 It is essential to note that all research involve cost to participants even if just their time, and each research study has the potential to hurt participants, hence it is important to ensure that the merit of research outweighs the costs and risks. There are five categories into which studies may be categorised based on the possible amount of injury or discomfort that they may expose the participants to. 11

- No anticipated effects

- Temporary discomfort

- Unusual levels of temporary discomfort

- Risk of permanent damage

- Certainty of permanent damage

The concept of fairness and the application of moral principles to ensure equitable treatment. According to this research tenet, the researcher must treat participants fairly and always prioritise the needs of the research subjects over the study’s aim. 8,11 Research participants must be fairly chosen, and that exclusion and inclusion criteria must be accurately stated in the research’s findings. 8 In addition, there is no unjust hardship associated with participating in research on certain groups, and the participant recruitment method is fair. Furthermore, the rewards for research involvement are fairly distributed; research participants are not exploited, and research rewards are accessible to everybody equally. 8

An Introduction to Research Methods for Undergraduate Health Profession Students Copyright © 2023 by Faith Alele and Bunmi Malau-Aduli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Ethical Issues in Research: Perceptions of Researchers, Research Ethics Board Members and Research Ethics Experts

Marie-josée drolet.

1 Department of Occupational Therapy (OT), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR), Trois-Rivières (Québec), Canada

Eugénie Rose-Derouin

2 Bachelor OT program, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR), Trois-Rivières (Québec), Canada

Julie-Claude Leblanc

Mélanie ruest, bryn williams-jones.

3 Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health, Université de Montréal, Montréal (Québec), Canada