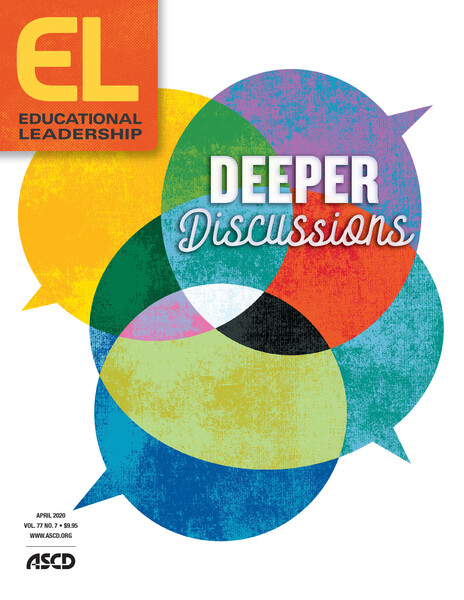

A Better Way to Assess Discussions

Nothing to "Dread"

Assessing what matters, into the spider verse, a "symbolic" grade, apps for that, next generation assessment.

Premium Resource

Figure 1. Graded Spider Web Discussion Rubric

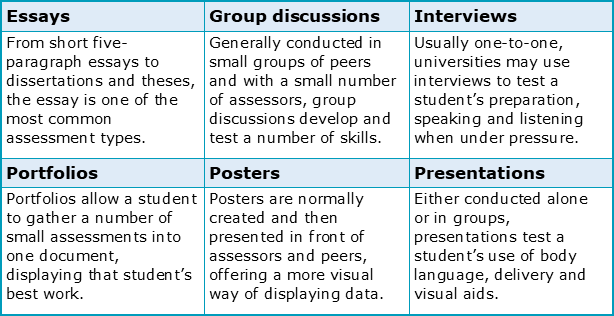

A Better Way to Assess Discussions - table

| Because this is a team effort, there will be a team grade. The whole class will get the SAME grade. The following list indicates what you need to accomplish, as a class, to earn an A. Have a truly hard-working, analytical discussion that includes these factors. |

| 1. Everyone has participated in a meaningful and substantive way and, more or less, equally. |

| 2. A sense of balance and order prevails; focus is on one speaker at a time and one idea at a time. The discussion is lively, and the pace is right (not hyper or boring). |

| 3. The discussion builds and there is an attempt to resolve questions and issues before moving on to new ones. Big ideas and deep insights are not brushed over or missed. |

| 4. Comments are not lost, the loud or verbose students do not dominate, the shy and quiet students are encouraged. |

| 5. Students listen carefully and respectfully to one another. For example, no one talks, daydreams, rustles papers, makes faces, or uses phones or laptops when someone else is speaking because this communicates disrespect and undermines the discussion as a whole. Also, no one gives sarcastic or glib comments. |

| 6. Everyone is clearly understood. Any comments that are not heard or understood are urged to be repeated. |

| 7. Students take risks and dig for deep meaning, new insights. |

| 8. Students back up what they say with examples and quotations regularly throughout the discussion. Dialectical Journals and/or the text are read from out loud OFTEN to support arguments. |

| 9. Literary features/writing style and class vocabulary are given special attention and mention. There is at least one literary feature AND one new vocabulary word used correctly in each discussion. |

| The class earns an A by doing all these items at an impressively high level. (Rare and difficult!) The class earns a B by doing most things on this list. (A pretty good discussion.) The class earns a C for doing half or slightly more than half of what's on this list. The class earns a D by doing less than half of what's on the list. The class earns an F if the discussion is a real mess or a complete dud and virtually nothing on this list is accomplished or genuinely attempted. Unprepared or unwilling students will bring the group down as a whole. Please remember this as you read and take notes on the assignment and prepare for class discussion. |

| Source: Wiggins, A. (2017). The best class you never taught: How spider web discussion can turn students into learning leaders. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. |

Reflect & Discuss

➛ How do you currently assess your class discussions? Do your methods tend to reward volume over quality?

➛ Could a group grade for class discussions better serve your students? If so, would the grade count?

➛ How might you use Wiggins's rubric to facilitate deeper academic conversations?

1 World Economic Forum. (2016). The 10 skills you need to thrive in the fourth industrial revolution . [Blog post].

2 Wiggins, A. (2017). The best class you never taught: How spider web discussion can turn students into learning leaders . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Alexis Wiggins has worked as a high-school English teacher, instructional coach, and consultant for curriculum and assessment. Her book, The Best Class You Never Taught: How Spider Web Discussion Can Turn Students into Learning Leaders (ASCD), helps transform classrooms through collaborative inquiry. Alexis is currently the Curriculum Coordinator at The John Cooper School in The Woodlands, TX.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., related articles.

The Value of Descriptive, Multi-Level Rubrics

Giving Retakes Their Best Chance to Improve Learning

The Way We Talk About Assessment Matters

The Assessment System That Made Me Love Grading Again (Yes, Really!)

Fine-Tuning Assessments for Better Feedback

From our issue.

Center for Teaching

Assessing student learning.

| Fisher, M. R., Jr., & Bandy, J. (2019). Assessing Student Learning. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/assessing-student-learning/. |

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

Assessment is more than grading, assessment plans, methods of student assessment, generative and reflective assessment, teaching guides related to student assessment, references and additional resources.

Student assessment is, arguably, the centerpiece of the teaching and learning process and therefore the subject of much discussion in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Without some method of obtaining and analyzing evidence of student learning, we can never know whether our teaching is making a difference. That is, teaching requires some process through which we can come to know whether students are developing the desired knowledge and skills, and therefore whether our instruction is effective. Learning assessment is like a magnifying glass we hold up to students’ learning to discern whether the teaching and learning process is functioning well or is in need of change.

To provide an overview of learning assessment, this teaching guide has several goals, 1) to define student learning assessment and why it is important, 2) to discuss several approaches that may help to guide and refine student assessment, 3) to address various methods of student assessment, including the test and the essay, and 4) to offer several resources for further research. In addition, you may find helfpul this five-part video series on assessment that was part of the Center for Teaching’s Online Course Design Institute.

What is student assessment and why is it Important?

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning” (2001, p. 5). An intentional and thorough assessment of student learning is vital because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction — “Backward Design”— that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggins and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course goals. Assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred (2005, p. 18). Their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, p. 18). [1]

Not only does effective assessment provide us with valuable information to support student growth, but it also enables critically reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, argues that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students (1995). Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the intentional and meaningful development of one’s teaching philosophy and practices. According to Brookfield, referencing higher education faculty, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 17). One important lens through which we may reflect on our teaching is our student evaluations and student learning assessments. This reflection allows educators to determine where their teaching has been effective in meeting learning goals and where it has not, allowing for improvements. Student assessment, then, both develop the rationale for pedagogical choices, and enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching.

The scholarship of teaching and learning discusses two general forms of assessment. The first, summative assessment , is one that is implemented at the end of the course of study, for example via comprehensive final exams or papers. Its primary purpose is to produce an evaluation that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful for communicating final evaluations of student achievement, it does so without providing opportunities for students to reflect on their progress, alter their learning, and demonstrate growth or improvement; nor does it allow instructors to modify their teaching strategies before student learning in a course has concluded (Maki, 2002).

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning at intermediate points before any summative form. Its fundamental purpose is to help students during the learning process by enabling them to reflect on their challenges and growth so they may improve. By analyzing students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies” (Maki, 2002, p. 11). Pat Hutchings refers to as “assessment behind outcomes”: “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, p. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes all manner of coursework with feedback, discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves (Brown and Knight, 1994).

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed below) can either be summative or formative depending on when and how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in Assessing Learners in Higher Education caution against a conflation of the method (e.g., an essay) with the goal (formative or summative): “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback” (1994, p. 17). If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, but he or she does not take the requisite time or effort to provide extensive feedback to students, the assessment effectively functions as a summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions (Brown and Knight, 1994). Indeed, feedback and discussion are critical factors that distinguish between formative and summative assessment; formative assessment is only as good as the feedback that accompanies it.

It is not uncommon to conflate assessment with grading, but this would be a mistake. Student assessment is more than just grading. Assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to students and instructors about learning and teaching, respectively. Grading, on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. (2001) merely involves affixing a number or letter to an assignment, giving students only the most minimal indication of their performance relative to a set of criteria or to their peers: “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest” (Stassen et al., 2001, p. 6). Grades are only the broadest of indicators of achievement or status, and as such do not provide very meaningful information about students’ learning of knowledge or skills, how they have developed, and what may yet improve. Unfortunately, despite the limited information grades provide students about their learning, grades do provide students with significant indicators of their status – their academic rank, their credits towards graduation, their post-graduation opportunities, their eligibility for grants and aid, etc. – which can distract students from the primary goal of assessment: learning. Indeed, shifting the focus of assessment away from grades and towards more meaningful understandings of intellectual growth can encourage students (as well as instructors and institutions) to attend to the primary goal of education.

Barbara Walvoord (2010) argues that assessment is more likely to be successful if there is a clear plan, whether one is assessing learning in a course or in an entire curriculum (see also Gelmon, Holland, and Spring, 2018). Without some intentional and careful plan, assessment can fall prey to unclear goals, vague criteria, limited communication of criteria or feedback, invalid or unreliable assessments, unfairness in student evaluations, or insufficient or even unmeasured learning. There are several steps in this planning process.

- Defining learning goals. An assessment plan usually begins with a clearly articulated set of learning goals.

- Defining assessment methods. Once goals are clear, an instructor must decide on what evidence – assignment(s) – will best reveal whether students are meeting the goals. We discuss several common methods below, but these need not be limited by anything but the learning goals and the teaching context.

- Developing the assessment. The next step would be to formulate clear formats, prompts, and performance criteria that ensure students can prepare effectively and provide valid, reliable evidence of their learning.

- Integrating assessment with other course elements. Then the remainder of the course design process can be completed. In both integrated (Fink 2013) and backward course design models (Wiggins & McTighe 2005), the primary assessment methods, once chosen, become the basis for other smaller reading and skill-building assignments as well as daily learning experiences such as lectures, discussions, and other activities that will prepare students for their best effort in the assessments.

- Communicate about the assessment. Once the course has begun, it is possible and necessary to communicate the assignment and its performance criteria to students. This communication may take many and preferably multiple forms to ensure student clarity and preparation, including assignment overviews in the syllabus, handouts with prompts and assessment criteria, rubrics with learning goals, model assignments (e.g., papers), in-class discussions, and collaborative decision-making about prompts or criteria, among others.

- Administer the assessment. Instructors then can implement the assessment at the appropriate time, collecting evidence of student learning – e.g., receiving papers or administering tests.

- Analyze the results. Analysis of the results can take various forms – from reading essays to computer-assisted test scoring – but always involves comparing student work to the performance criteria and the relevant scholarly research from the field(s).

- Communicate the results. Instructors then compose an assessment complete with areas of strength and improvement, and communicate it to students along with grades (if the assignment is graded), hopefully within a reasonable time frame. This also is the time to determine whether the assessment was valid and reliable, and if not, how to communicate this to students and adjust feedback and grades fairly. For instance, were the test or essay questions confusing, yielding invalid and unreliable assessments of student knowledge.

- Reflect and revise. Once the assessment is complete, instructors and students can develop learning plans for the remainder of the course so as to ensure improvements, and the assignment may be changed for future courses, as necessary.

Let’s see how this might work in practice through an example. An instructor in a Political Science course on American Environmental Policy may have a learning goal (among others) of students understanding the historical precursors of various environmental policies and how these both enabled and constrained the resulting legislation and its impacts on environmental conservation and health. The instructor therefore decides that the course will be organized around a series of short papers that will combine to make a thorough policy report, one that will also be the subject of student presentations and discussions in the last third of the course. Each student will write about an American environmental policy of their choice, with a first paper addressing its historical precursors, a second focused on the process of policy formation, and a third analyzing the extent of its impacts on environmental conservation or health. This will help students to meet the content knowledge goals of the course, in addition to its goals of improving students’ research, writing, and oral presentation skills. The instructor then develops the prompts, guidelines, and performance criteria that will be used to assess student skills, in addition to other course elements to best prepare them for this work – e.g., scaffolded units with quizzes, readings, lectures, debates, and other activities. Once the course has begun, the instructor communicates with the students about the learning goals, the assignments, and the criteria used to assess them, giving them the necessary context (goals, assessment plan) in the syllabus, handouts on the policy papers, rubrics with assessment criteria, model papers (if possible), and discussions with them as they need to prepare. The instructor then collects the papers at the appropriate due dates, assesses their conceptual and writing quality against the criteria and field’s scholarship, and then provides written feedback and grades in a manner that is reasonably prompt and sufficiently thorough for students to make improvements. Then the instructor can make determinations about whether the assessment method was effective and what changes might be necessary.

Assessment can vary widely from informal checks on understanding, to quizzes, to blogs, to essays, and to elaborate performance tasks such as written or audiovisual projects (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight (1994) that are important to consider.

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style (1980). The American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) also has found that intensive writing is a “high impact” teaching practice likely to help students in their engagement, learning, and academic attainment (Kuh 2008).

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them.

- Essays encompass a wide array of narrative forms and lengths, from short descriptive essays to long analytical or creative ones. Shorter essays are often best suited to assess student’s understanding of threshold concepts and discrete analytical or writing skills, while longer essays afford assessments of higher order concepts and more complex learning goals, such as rigorous analysis, synthetic writing, problem solving, or creative tasks.

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments. Students need performance criteria and prompts that urge them to go beyond mere memorization and comprehension, but encourage the highest levels of learning on Bloom’s Taxonomy . This may open the possibility for essay assignments that go beyond the common summary or descriptive essay on a given topic, but demand, for example, narrative or persuasive essays or more creative projects.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is sometimes not the case. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist, or provide students to resources that will enhance their writing skills. Faculty may also encourage students to attend writing workshops at university writing centers, such as Vanderbilt University’s Writing Studio .

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been a gold standard of assessment, particularly in post-secondary education. Many educators prefer them because they can be highly effective, they can be standardized, they are easily integrated into disciplines with certification standards, and they are efficient to implement since they can allow for less labor-intensive feedback and grading. They can involve multiple forms of questions, be of varying lengths, and can be used to assess multiple levels of student learning. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams typically focus on the assessment of students’ knowledge of facts, figures, and other discrete information crucial to a course. While they can involve questioning that demands students to engage in higher order demonstrations of comprehension, problem solving, analysis, synthesis, critique, and even creativity, such exams often require more time to prepare and validate.

- Exam questions can be multiple choice, true/false, or other discrete answer formats, or they can be essay or problem-solving. For more on how to write good multiple choice questions, see this guide .

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and therefore can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. Further, when exams are offered infrequently, or when they have high stakes by virtue of their heavy weighting in course grade schemes or in student goals, they may accompany violations of academic integrity.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well on the exam? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgment and the capacities for critical meta-cognition – to learn how to learn. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both the processes and products of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student self-assessment in the classroom ensures students evaluate their performance and the process of learning that led to it. Self-assessment thus provides a sense of student ownership of their learning and can lead to greater investment and engagement. It also enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process with their peers.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is not self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor]” (1994, p. 52). Self-assessment can involve self-grading, but instructors of record retain the final authority to determine and assign grades.

- To accurately and thoroughly self-assess, students require clear learning goals for the assignment in question, as well as rubrics that clarify different performance criteria and levels of achievement for each. These rubrics may be instructor-designed, or they may be fashioned through a collaborative dialogue with students. Rubrics need not include any grade assignation, but merely descriptive academic standards for different criteria.

- Students may not have the expertise to assess themselves thoroughly, so it is helpful to build students’ capacities for self-evaluation, and it is important that they always be supplemented with faculty assessments.

- Students may initially resist instructor attempts to involve themselves in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work, or possibly because of habituation to more passive roles in the learning process. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance (1994).

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as unique as the instructor or the course. Common forms of self-assessment involve written or oral reflection on a student’s own work, including portfolio, logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, post-test reflections, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and, in return, have their own work evaluated as well. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken” (Brown and Knight, 1994, p. 52). However, it also provides students with other models of performance (e.g., different styles or narrative forms of writing), as well as the opportunity to teach, which can enable greater preparation, reflection, and meta-cognitive organization.

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Similar to self-assessment, students benefit from clear and specific learning goals and rubrics. Again, these may be instructor-defined or determined through collaborative dialogue.

- Also similar to self-assessment, it is important to not conflate peer assessment and peer grading, since grading authority is retained by the instructor of record.

- While student peer assessments are most often fair and accurate, they sometimes can be subject to bias. In competitive educational contexts, for example when students are graded normatively (“on a curve”), students can be biased or potentially game their peer assessments, giving their fellow students unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, in more cooperative teaching environments or in cases when they are friends with their peers, students may provide overly favorable evaluations. Also, other biases associated with identity (e.g., race, gender, or class) and personality differences can shape student assessments in unfair ways. Therefore, it is important for instructors to encourage fairness, to establish processes based on clear evidence and identifiable criteria, and to provide instructor assessments as accompaniments or correctives to peer evaluations.

- Students may not have the disciplinary expertise or assessment experience of the instructor, and therefore can issue unsophisticated judgments of their peers. Therefore, to avoid unfairness, inaccuracy, and limited comments, formative peer assessments may need to be supplemented with instructor feedback.

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor when possible, improves the reliability of the assessment data. It also ensures that students with diverse aptitudes and abilities can be assessed accurately and have equal opportunities to excel. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret and mis-evaluate student learning. Ultimately, they caution that, when multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement (Brown and Knight, 1994).

These are only a few of the many forms of assessment that one might use to evaluate and enhance student learning (see also ideas present in Brown and Knight, 1994). To this list of assessment forms and methods we may add many more that encourage students to produce anything from research papers to films, theatrical productions to travel logs, op-eds to photo essays, manifestos to short stories. The limits of what may be assigned as a form of assessment is as varied as the subjects and skills we seek to empower in our students. Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching has an ever-expanding array of guides on creative models of assessment that are present below, so please visit them to learn more about other assessment innovations and subjects.

Whatever plan and method you use, assessment often begins with an intentional clarification of the values that drive it. While many in higher education may argue that values do not have a role in assessment, we contend that values (for example, rigor) always motivate and shape even the most objective of learning assessments. Therefore, as in other aspects of assessment planning, it is helpful to be intentional and critically reflective about what values animate your teaching and the learning assessments it requires. There are many values that may direct learning assessment, but common ones include rigor, generativity, practicability, co-creativity, and full participation (Bandy et al., 2018). What do these characteristics mean in practice?

Rigor. In the context of learning assessment, rigor means aligning our methods with the goals we have for students, principles of validity and reliability, ethics of fairness and doing no harm, critical examinations of the meaning we make from the results, and good faith efforts to improve teaching and learning. In short, rigor suggests understanding learning assessment as we would any other form of intentional, thoroughgoing, critical, and ethical inquiry.

Generativity. Learning assessments may be most effective when they create conditions for the emergence of new knowledge and practice, including student learning and skill development, as well as instructor pedagogy and teaching methods. Generativity opens up rather than closes down possibilities for discovery, reflection, growth, and transformation.

Practicability. Practicability recommends that learning assessment be grounded in the realities of the world as it is, fitting within the boundaries of both instructor’s and students’ time and labor. While this may, at times, advise a method of learning assessment that seems to conflict with the other values, we believe that assessment fails to be rigorous, generative, participatory, or co-creative if it is not feasible and manageable for instructors and students.

Full Participation. Assessments should be equally accessible to, and encouraging of, learning for all students, empowering all to thrive regardless of identity or background. This requires multiple and varied methods of assessment that are inclusive of diverse identities – racial, ethnic, national, linguistic, gendered, sexual, class, etcetera – and their varied perspectives, skills, and cultures of learning.

Co-creation. As alluded to above regarding self- and peer-assessment, co-creative approaches empower students to become subjects of, not just objects of, learning assessment. That is, learning assessments may be more effective and generative when assessment is done with, not just for or to, students. This is consistent with feminist, social, and community engagement pedagogies, in which values of co-creation encourage us to critically interrogate and break down hierarchies between knowledge producers (traditionally, instructors) and consumers (traditionally, students) (e.g., Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009, p. 10; Weimer, 2013). In co-creative approaches, students’ involvement enhances the meaningfulness, engagement, motivation, and meta-cognitive reflection of assessments, yielding greater learning (Bass & Elmendorf, 2019). The principle of students being co-creators of their own education is what motivates the course design and professional development work Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching has organized around the Students as Producers theme.

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one and may be of assistance as you consider all of the factors that shape your assessment plan.

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Classroom Response Systems

- How People Learn

- Service-Learning and Community Engagement

- Syllabus Construction

- Teaching with Blogs

- Test-Enhanced Learning

- Assessing Student Learning (a five-part video series for the CFT’s Online Course Design Institute)

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Bandy, Joe, Mary Price, Patti Clayton, Julia Metzker, Georgia Nigro, Sarah Stanlick, Stephani Etheridge Woodson, Anna Bartel, & Sylvia Gale. Democratically engaged assessment: Reimagining the purposes and practices of assessment in community engagement . Davis, CA: Imagining America, 2018. Web.

Bass, Randy and Heidi Elmendorf. 2019. “ Designing for Difficulty: Social Pedagogies as a Framework for Course Design .” Social Pedagogies: Teagle Foundation White Paper. Georgetown University, 2019. Web.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ;Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31. Print.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Gelmon, Sherril B., Barbara Holland, and Amy Spring. Assessing Service-Learning and Civic Engagement: Principles and Techniques. Second Edition . Stylus, 2018. Print.

Kuh, George. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter , American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2008. Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. Print.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Walvoord, Barbara. Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print.

Weimer, Maryellen. Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria,

VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our teaching guide here .

Photo credit

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

The Science of Reading

2-day workshop sept 14 & 21, standards-based grading, 2-day workshop sept 17 & 24, social-emotional learning, 2-day workshop oct 22 & 29, engaging the 21st century learner, 4-day workshop oct 30, nov 6, 13, & 20, reclaiming the joy of teaching, full day workshop dec 7.

Assessing Student Learning: 6 Types of Assessment and How to Use Them

Assessing student learning is a critical component of effective teaching and plays a significant role in fostering academic success. We will explore six different types of assessment and evaluation strategies that can help K-12 educators, school administrators, and educational organizations enhance both student learning experiences and teacher well-being.

We will provide practical guidance on how to implement and utilize various assessment methods, such as formative and summative assessments, diagnostic assessments, performance-based assessments, self-assessments, and peer assessments.

Additionally, we will also discuss the importance of implementing standard-based assessments and offer tips for choosing the right assessment strategy for your specific needs.

Importance of Assessing Student Learning

Assessment plays a crucial role in education, as it allows educators to measure students’ understanding, track their progress, and identify areas where intervention may be necessary. Assessing student learning not only helps educators make informed decisions about instruction but also contributes to student success and teacher well-being.

Assessments provide insight into student knowledge, skills, and progress while also highlighting necessary adjustments in instruction. Effective assessment practices ultimately contribute to better educational outcomes and promote a culture of continuous improvement within schools and classrooms.

1. Formative assessment

Formative assessment is a type of assessment that focuses on monitoring student learning during the instructional process. Its primary purpose is to provide ongoing feedback to both teachers and students, helping them identify areas of strength and areas in need of improvement. This type of assessment is typically low-stakes and does not contribute to a student’s final grade.

Some common examples of formative assessments include quizzes, class discussions, exit tickets, and think-pair-share activities. This type of assessment allows educators to track student understanding throughout the instructional period and identify gaps in learning and intervention opportunities.

To effectively use formative assessments in the classroom, teachers should implement them regularly and provide timely feedback to students.

This feedback should be specific and actionable, helping students understand what they need to do to improve their performance. Teachers should use the information gathered from formative assessments to refine their instructional strategies and address any misconceptions or gaps in understanding. Formative assessments play a crucial role in supporting student learning and helping educators make informed decisions about their instructional practices.

Check Out Our Online Course: Standards-Based Grading: How to Implement a Meaningful Grading System that Improves Student Success

2. summative assessment.

Examples of summative assessments include final exams, end-of-unit tests, standardized tests, and research papers. To effectively use summative assessments in the classroom, it’s important to ensure that they are aligned with the learning objectives and content covered during instruction.

This will help to provide an accurate representation of a student’s understanding and mastery of the material. Providing students with clear expectations and guidelines for the assessment can help reduce anxiety and promote optimal performance.

Summative assessments should be used in conjunction with other assessment types, such as formative assessments, to provide a comprehensive evaluation of student learning and growth.

3. Diagnostic assessment

Diagnostic assessment, often used at the beginning of a new unit or term, helps educators identify students’ prior knowledge, skills, and understanding of a particular topic.

This type of assessment enables teachers to tailor their instruction to meet the specific needs and learning gaps of their students. Examples of diagnostic assessments include pre-tests, entry tickets, and concept maps.

To effectively use diagnostic assessments in the classroom, teachers should analyze the results to identify patterns and trends in student understanding.

This information can be used to create differentiated instruction plans and targeted interventions for students struggling with the upcoming material. Sharing the results with students can help them understand their strengths and areas for improvement, fostering a growth mindset and encouraging active engagement in their learning.

4. Performance-based assessment

Performance-based assessment is a type of evaluation that requires students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities through the completion of real-world tasks or activities.

The main purpose of this assessment is to assess students’ ability to apply their learning in authentic, meaningful situations that closely resemble real-life challenges. Examples of performance-based assessments include projects, presentations, portfolios, and hands-on experiments.

These assessments allow students to showcase their understanding and application of concepts in a more active and engaging manner compared to traditional paper-and-pencil tests.

To effectively use performance-based assessments in the classroom, educators should clearly define the task requirements and assessment criteria, providing students with guidelines and expectations for their work. Teachers should also offer support and feedback throughout the process, allowing students to revise and improve their performance.

Incorporating opportunities for peer feedback and self-reflection can further enhance the learning process and help students develop essential skills such as collaboration, communication, and critical thinking.

5. Self-assessment

Self-assessment is a valuable tool for encouraging students to engage in reflection and take ownership of their learning. This type of assessment requires students to evaluate their own progress, skills, and understanding of the subject matter. By promoting self-awareness and critical thinking, self-assessment can contribute to the development of lifelong learning habits and foster a growth mindset.

Examples of self-assessment activities include reflective journaling, goal setting, self-rating scales, or checklists. These tools provide students with opportunities to assess their strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. When implementing self-assessment in the classroom, it is important to create a supportive environment where students feel comfortable and encouraged to be honest about their performance.

Teachers can guide students by providing clear criteria and expectations for self-assessment, as well as offering constructive feedback to help them set realistic goals for future learning.

Incorporating self-assessment as part of a broader assessment strategy can reinforce learning objectives and empower students to take an active role in their education.

Reflecting on their performance and understanding the assessment criteria can help them recognize both short-term successes and long-term goals. This ongoing process of self-evaluation can help students develop a deeper understanding of the material, as well as cultivate valuable skills such as self-regulation, goal setting, and critical thinking.

6. Peer assessment

Peer assessment, also known as peer evaluation, is a strategy where students evaluate and provide feedback on their classmates’ work. This type of assessment allows students to gain a better understanding of their own work, as well as that of their peers.

Examples of peer assessment activities include group projects, presentations, written assignments, or online discussion boards.

In these settings, students can provide constructive feedback on their peers’ work, identify strengths and areas for improvement, and suggest specific strategies for enhancing performance.

Constructive peer feedback can help students gain a deeper understanding of the material and develop valuable skills such as working in groups, communicating effectively, and giving constructive criticism.

To successfully integrate peer assessment in the classroom, consider incorporating a variety of activities that allow students to practice evaluating their peers’ work, while also receiving feedback on their own performance.

Encourage students to focus on both strengths and areas for improvement, and emphasize the importance of respectful, constructive feedback. Provide opportunities for students to reflect on the feedback they receive and incorporate it into their learning process. Monitor the peer assessment process to ensure fairness, consistency, and alignment with learning objectives.

Implementing Standard-Based Assessments

Standard-based assessments are designed to measure students’ performance relative to established learning standards, such as those generated by the Common Core State Standards Initiative or individual state education guidelines.

By implementing these types of assessments, educators can ensure that students meet the necessary benchmarks for their grade level and subject area, providing a clearer picture of student progress and learning outcomes.

To successfully implement standard-based assessments, it is essential to align assessment tasks with the relevant learning standards.

This involves creating assessments that directly measure students’ knowledge and skills in relation to the standards rather than relying solely on traditional testing methods.

As a result, educators can obtain a more accurate understanding of student performance and identify areas that may require additional support or instruction. Grading formative and summative assessments within a standard-based framework requires a shift in focus from assigning letter grades or percentages to evaluating students’ mastery of specific learning objectives.

This approach encourages educators to provide targeted feedback that addresses individual student needs and promotes growth and improvement. By utilizing rubrics or other assessment tools, teachers can offer clear, objective criteria for evaluating student work, ensuring consistency and fairness in the grading process.

Tips For Choosing the Right Assessment Strategy

When selecting an assessment strategy, it’s crucial to consider its purpose. Ask yourself what you want to accomplish with the assessment and how it will contribute to student learning. This will help you determine the most appropriate assessment type for your specific situation.

Aligning assessments with learning objectives is another critical factor. Ensure that the assessment methods you choose accurately measure whether students have met the desired learning outcomes. This alignment will provide valuable feedback to both you and your students on their progress. Diversifying assessment methods is essential for a comprehensive evaluation of student learning.

By using a variety of assessment types, you can gain a more accurate understanding of students’ strengths and weaknesses. This approach also helps support different learning styles and reduces the risk of overemphasis on a single assessment method.

Incorporating multiple forms of assessment, such as formative, summative, diagnostic, performance-based, self-assessment, and peer assessment, can provide a well-rounded understanding of student learning. By doing so, educators can make informed decisions about instruction, support, and intervention strategies to enhance student success and overall classroom experience.

Challenges and Solutions in Assessment Implementation

Implementing various assessment strategies can present several challenges for educators. One common challenge is the limited time and resources available for creating and administering assessments. To address this issue, teachers can collaborate with colleagues to share resources, divide the workload, and discuss best practices.

Utilizing technology and online platforms can also streamline the assessment process and save time. Another challenge is ensuring that assessments are unbiased and inclusive.

To overcome this, educators should carefully review assessment materials for potential biases and design assessments that are accessible to all students, regardless of their cultural backgrounds or learning abilities.

Offering flexible assessment options for the varying needs of learners can create a more equitable and inclusive learning environment. It is essential to continually improve assessment practices and seek professional development opportunities.

Seeking support from colleagues, attending workshops and conferences related to assessment practices, or enrolling in online courses can help educators stay up-to-date on best practices while also providing opportunities for networking with other professionals.

Ultimately, these efforts will contribute to an improved understanding of the assessments used as well as their relevance in overall student learning.

Assessing student learning is a crucial component of effective teaching and should not be overlooked. By understanding and implementing the various types of assessments discussed in this article, you can create a more comprehensive and effective approach to evaluating student learning in your classroom.

Remember to consider the purpose of each assessment, align them with your learning objectives, and diversify your methods for a well-rounded evaluation of student progress.

If you’re looking to further enhance your assessment practices and overall professional development, Strobel Education offers workshops , courses , keynotes , and coaching services tailored for K-12 educators. With a focus on fostering a positive school climate and enhancing student learning, Strobel Education can support your journey toward improved assessment implementation and greater teacher well-being.

Related Posts

Problems with the Current Grading System

Reimagining Grading and Assessment Practices in 21st Century Education

Implementing Competency-Based Education in Your Grading System

Subscribe to our blog today, keep in touch.

Copyright 2024 Strobel Education, all rights reserved.

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Learning Through Discussion

Discussions can be meaningful and engaging learning experiences: dynamic, eye-opening, and generative. However, like any class activity, they require planning and preparation. Without that, discussion challenges can arise in the form of unequal participation, unclear learning outcomes, or low engagement. This resource presents key considerations in class discussions and offers strategies for how instructors can prepare and engage in effective classroom discussions.

On this page:

- The What and Why of Class Discussion

Identifying your Course Context

- Plan for Classroom Discussion

- Warm up Classroom Discussion

- Engage in Classroom Discussion

- Wrap up Classroom Discussion

Leveraging Asynchronous Discussion Spaces

- References and Further Reading

The CTL is here to help!

Seeking additional support with discussion pedagogy? Email [email protected] to schedule a 1-1 consultation. For support with any of the Columbia tools discussed below, email [email protected] or join our virtual office hours .

Interested in inviting the CTL to facilitate a session on this topic for your school, department, or program? Visit our Workshops To Go page for more information.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Learning Through. DIscussion. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/learning-through-discussion/

The What and Why of Class Discussion

Class discussion can take many forms, from structured prompts and assignments to more casual or informal conversations. Regardless of class context (e.g.: a seminar, large lecture, or lab course) or the form (e.g.: in-person or asynchronous) discussion takes, it offers a number of benefits to students’ learning. As an active learning technique, class discussion requires students to be co-constructors of their learning. Research shows that students learn more when they actively participate in their learning, rather than passively listen. Furthermore, studies have also shown that “student participation, encouragement, and peer-to-peer interaction was consistently and positively related to the development of critical thinking skills” (Howard, 2015, pp. 6). Class discussion has also been linked to greater student motivation, improved communication skills, and higher grades (Howard, 2015). But just like effective lectures or assignments require planning and preparation, so too does class discussion.

The following sections offer a framework and strategies for learning through discussion. These strategies are organized around four key phases: planning for classroom discussion, warming up for classroom discussion, engaging in classroom discussion, and wrapping up classroom discussion.

While the strategies and considerations provided throughout this resource are adaptable across course contexts, it is important to recognize instructors’ varied course formats, and how discussion might differ across them. This section identifies a few of these contexts, and reviews how these contexts might shape instructors’ engagement with both this resource and class discussion more broadly.

I teach a discussion-based course

Small classes and seminars use discussion-based pedagogies, though it can be challenging to get every student to contribute to discussions. It is important to create multiple opportunities for engagement and not just rely on whole group discussion. Pair and small group discussions can create trust among students and give them the confidence to speak up in the larger group. Instructors of discussion-based courses can extend in-class discussions into the asynchronous space. These inclusive moves allow students to contribute to discussions in multiple ways.

I do not teach a discussion-based course

Whether teaching a large lecture course, a lab course, or other non-discussion based course, students will still benefit from interacting with each other and learning through discussion. Small group or pair discussion can be less intimidating for students regardless of class size and help create a sense of community that impacts learning.

I teach a course that may have some Hybrid/HyFlex meetings.

In-person classes might sometimes offer hybrid or HyFlex opportunities for students to accommodate extenuating circumstances. In a hybrid/HyFlex course session, students participating in-person and remotely should have equal opportunities to contribute to discussions. To make this a reality, advanced preparation involves thinking through the logistics using discussion activities, roles and responsibilities (if working with TA(s)), classroom technologies (e.g., ceiling microphones available in the classroom; asking in-person students to bring a mobile device and headset if possible to engage with their remote peers), and determining the configurations if using discussion groups or paired work (both in a socially distanced classroom, and if asking both in-person and remote students to discuss together in breakout groups).

Planning for Classroom Discussion

Regardless of your course context, there are some general considerations for planning a class discussion; these considerations include: the goals and expectations, the modality of discussion, and the questions you might use to prompt discussion. The following section offers some questions for reflection, alongside ideas and strategies to address these considerations.

Goals & Expectations

What is the goal of the discussion? How will it support student learning? What are your expectations of student participation and contributions to the discussion? How will you communicate the goals and expectations to students?

Articulate the goals of discussion : Consider both the content you want your students to learn and the skills you want them to apply and develop. These goals will inform the learner-centered strategies and digital tools you use during discussion.

Communicate the purpose (not just the topic) of discussion: Sharing learning goals will help students understand why discussion is being used and how it will contribute to their learning.

Specify what you expect of student contributions to the discussion and how they will be assessed: Be explicit about what students should include in their contributions to make them substantive, and model possible ways of responding. Guide students in how they can contribute substantively to their peers’ live responses or online posts. You might consider asking students to use the 3CQ model:

- Compliment—I like that ___ because…;

- Comment—I agree/disagree with (specific point/idea) because…;

- Connection—I also thought that…;

- Question—I wonder why…

Establish discussion guidelines: Communicate expectations for class discussion. Be sure to include desired behaviors/etiquette and how technologies and tools for discussion will be used. Students in all classes can benefit from discussion guidelines as they help to clearly identify and establish expectations for student success. For more support with getting started, see the Barnard Center for Engaged Pedagogy’s resource on Crafting Community Agreements . Additionally, while there are some shared general discussion guidelines, there are also some specific considerations for asynchronous discussions:

Sample Discussion Guidelines:

- Refer to classmates by name.

- Allow everyone the chance to speak (“Take Space, Make Space”).

- Constructively critique ideas, not individuals.

- Listen actively without interrupting.

- Contribute questions, ideas, or resources.

Sample Asynchronous Discussion Guidelines:

- Respond to discussion posts within # of hours or days.

- Review one’s own writing for clarity before posting, being mindful of how it may be interpreted by others.

- Prioritize building upon or challenging the strongest ideas presented in a post instead of only focusing on the weakest aspects.

- Acknowledge something someone else said.

- Build on their comment by connecting with course content, adding an example or observation.

- Conclude with critical thinking or socratic questions.

Invite students to revise, contribute to, or co-create the guidelines. One way to do this is to facilitate a discussion about discussions, asking students to identify what the characteristics of an effective discussion are. This will encourage their ownership of the guidelines. Post the guidelines in CourseWorks and refer to them as needed.

In what modality/modalities will the discussion take place (in-person/live, asynchronous, or a blend of both)?

The modality of your class discussion may determine the tools and technologies that you ask students to engage with. Thus, it is important to determine early on how you would like students to engage in discussion and what tools you will use to support their engagement. Consider leveraging your asynchronous course spaces (e.g., CourseWorks), which can help students both prepare for an in-class discussion, as well expand upon and continue in-class discussions. For support with setting up asynchronous discussions, see the Leveraging Asynchronous Discussion Spaces section below.

What prompts will be used for discussion? Who will come up with those prompts (e.g.: instructor, TA, or students)?

The questions you ask and how you ask them are important for leading an effective discussion. Discussion questions do not have to be instructor-generated; asking students to generate discussion prompts is a great way to engage them in their learning.

Draft open-ended questions that advance student learning and inspire a range of answers (avoiding closed-ended, vague, or leading questions). Vary question complexity over the course of a discussion. If there’s one right answer, ask students about their process to get to the right answer.

The following table features sample questions that increase in cognitive complexity and is based on the six categories of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy.

| Questions that assess basic knowledge or recollection of subject matter. | “What is the purpose of X?” “Describe/define X.” “What happened after X?” “Why did X happen?” | |

| Questions that ask students to explain, interpret, or give examples. | “What was the contribution of X?” “What was the main idea?” “Give an example of X…” | |

| Questions that ask students to use their knowledge/skills in new ways. | “How is X an example of Y?” “How is X related to Y?” “Can you apply this method to…?” | |

| Questions that ask students to draw connections. | “Compare/contrast X and Y.” “What’s the importance of X?” “How is this similar to X?” | |

| Questions that ask students to make judgements and assessments. | “How would you assess X?” “Is there a better solution to X?” “How effective is X?” | |

| Questions that ask students to combine ideas and knowledge. | “How would you design X?” “What’s a new use for X?” “Other ways to achieve X?” | |

Warming up for Classroom Discussion

Get students comfortable talking with their peers, you, and the TA(s) (as applicable) from the start of the course. Create opportunities for students to have pair or small group conversations to get to know one another and connect as a community. Regardless of your class size or context (i.e.: seminars, large-lecture classes, labs), for discussions to become a norm in your course, you will need to build community early on in the course.

Get students talking early and often to foster community

How will you make peer-to-peer engagement an integral part of your class? How can you get students talking to each other?

To encourage student participation and peer-to-peer interaction, create early and frequent opportunities for students to share and talk with each other. These opportunities can help make students more comfortable with participating in discussion, as well as help build rapport and foster trust amongst class members. Icebreakers and small group discussion opportunities provide great ways to get students talking, especially in large-enrollment classes where students may feel less connection with their peers (see sample icebreakers below ). For additional support with building community in your course, see the CTL’s Community Building in Online and Hybrid (HyFlex) Courses resource. (Although this resource emphasizes online and hybrid/HyFlex modalities, the strategies provided are applicable across all course modalities.)

Establish class norms around discussion and participation

How can you communicate class norms around discussion and participation on day one?

The first class meeting is an opportunity to warm students up to class discussion and participation from the outset. Rather than letting norms of passivity establish over the first couple of weeks, you can use the first class meeting to signal to students they will be expected to participate or interact with their peers regularly. You might ask students to do a welcoming icebreaker on the first day, or you might invite questions and syllabus discussion. No matter the activity, establishing a norm around discussion and participation at the outset will help warm students up to participating and contributing to later discussions; these norms can also be further supported by your discussion guidelines . Icebreakers: Icebreakers are a great way to establish a positive course climate and encourage student-student, as well as instructor-student, interactions. Some ideas for icebreaker activities related to discussion include:

- (Meta)Discussion about Discussions: In small groups during class, or using a CourseWorks discussion board , students introduce themselves to each other, and share their thoughts on what are the qualities of good and bad discussions.

- Course Content: Ask students to share their thoughts about a big question that the course addresses or ask students what comes to mind when they think of an important course concept. You could even ask students to scan the syllabus and share about a particular topic or reading they are most excited about.

Engaging in Classroom Discussion

With all of your preparation and planning complete, there are some important considerations you will need to make with both your students and yourself in mind. This section offers some strategies for engaging in classroom discussion.

Involve students in discussion

How will you engage all of your students in the discussion? How will you make discussion and your expectations about student participation explicit and integral to the class?

Involving your students in class discussion will allow for more student voices and perspectives to be contributed to the conversation. You might consider leveraging the time before and after class or office hours to have informal conversations and build rapport with students. Additionally, having students rotate roles and responsibilities can keep them focused and engaged.

Student roles: Engage all students by asking them to volunteer for and rotate through roles such as facilitator, summarizer, challenger, etc. In large-enrollment courses, these roles can be assigned in small group or pair discussions. For an asynchronous discussion, roles might include: discussion starter / original poster, connector to research, connector to theory. Additional roles might include: timekeeper, notetaker, discussion starter, wrapper, and student monitor:

- Discussion starter / original poster: Involve students in initiating the discussion. Designate 2–3 students per discussion to spark the conversation with a question, quotation, an example, or link to previous course content.

- Discussion wrapper: Engage students in facilitating the discussion. Help students grasp take-aways. Designate 2-3 students per discussion to wrap up the discussion by identifying themes, extracting key ideas, or listing questions to explore further.

- Student monitor: Ask a student (on a rotating basis) or TA(s) if applicable, to monitor the Zoom chat (in hybrid/HyFlex courses) or the CourseWorks Discussion Boards (when leveraging asynchronous discussion spaces). The monitors can then flag important points for the class or read off the questions that are being posed.

Student-generated questions: Prepare students for discussion and involve them in asking and answering peer questions about the topic. Invite students to post questions to a CourseWorks Discussion before class, or share their questions during the discussion. If students are expected to respond to their peer’s questions, they need to be told and guided how to do so. Highlight and use insightful student questions to prime or further the discussion.

Student-led presentations: In smaller seminar-style classes or labs, invite students to give informal presentations. You might ask them to share examples that relate to the topic or concept being discussed, or respond to a targeted prompt.

Determine your role in discussion

How will you facilitate discussion? What will your presence be in asynchronous discussion spaces? What can students expect of your role in the discussion?

Make your role (or that of your co-instructor(s) and/or TA(s)) in the discussion explicit so that students know what to expect of your presence, reinforcement of the discussion guidelines, and receipt of feedback.

Actively guide the discussion to make it easy for students to do most of the talking and/or posting. This includes being present, modeling contributions, asking questions, using students’ names, giving timely feedback, affirming student contributions, and making inclusive moves such as including as many voices and perspectives and addressing issues that may arise during a conversation.

- For in-class discussions , additional strategies include actively listening, giving students time to think before responding, repeating questions, and warm calling. (Unlike cold calling, warm calling is when students do pre-work and are told in advance that they will be asked to share their or their group’s response. This technique can minimize student anxiety, as well as produce higher quality responses.)

- For asynchronous discussions , additional strategies include having parallel discussions in small groups on CourseWorks, and inviting students to post videos, audio clips, or images such as drawings, maps, charts, etc.

Manage the discussion and intervene when necessary : Manage dynamics, recognizing that your classroom is influenced by societal norms and expectations that may be inherently inequitable. Moderate the ongoing discussion to make sure all students have the opportunity to contribute. Ask students to explain or provide evidence to support their contributions, connect their contributions to specific course concepts and readings, redirect or keep the conversation on track, and revisit discussion guidelines as needed.

For large-enrollment courses, you might ask TAs or course assistants to join small groups or monitor discussion board posting. While it’s important for students to do most of the talking and posting, TAs can support students in the discussion, and their presence can help keep the discussion on track. If you have TAs who lead discussion sections, you might consider sharing some of these discussion management strategies and considerations with them, and discuss how the discussion sections can and will expand upon discussions from the larger class.

Give students time to think before, during, and after the discussion

Thinking time will allow students to prepare more meaningful contributions to the discussion and creates opportunities for more students, not just the ones that are the quickest to respond, to contribute to the conversation. Comfort with silence is important following a posed question. Some thinking time activities include:

- “ Silent meeting ” (Armstrong, 2020): Devote class time to students silently engaging with course materials and commenting in a shared document. You can follow this “silent meeting” with small group discussions. In a large enrollment class, this strategy can allow students to engage more deeply and collaboratively with material and their peers.

- Think-Pair-Share : Give students time to think before participating. In response to an open-ended question, ask students to first think on their own for a few minutes, then pair up to discuss their ideas with their partner. Finally, ask a few pairs to share their main takeaways with the whole class.

- Discussion pause : Give students time to think and reflect on the discussion so far. Pause the discussion for a few minutes for students to independently restate the question, issue, or problem, and summarize the points made. Encourage students to write down new insights, unanswered questions, etc.

- Extend the discussion: Encourage students to continue the class discussion by leveraging asynchronous course spaces (e.g.: CourseWorks discussion board). You may ask students to summarize the discussion, extend the discussion by contributing new ideas, or pose follow-up questions that will be discussed asynchronously or used to begin the next in-class discussion.

- Polls to launch the discussion : Pose a poll closed-ended question and give students time to think and respond individually. See responses in real time and ask students to discuss the results. This can be a great warm up activity for a pair, small group, or whole class discussion, especially in large classes in which it may be more challenging to engage all students.

Wrapping up Classroom Discussion

Ensure that the discussion meets the learning objectives of the course or class session, and that students are leaving the discussion with the knowledge and skills that you want them to acquire. Give students an opportunity to reflect on and share what they have learned. This will help them make connections between other class material and previous class discussions. It is also an opportunity for you to gauge how the discussion went and consider what you might need to clarify or shift for future discussions.

Debrief the Discussion

How will you know the discussion has met the learning objectives of the course or class session? How will you ensure students make connections between broader course concepts and the discussion?

Set aside time to debrief the discussion. This might be groups sharing out their discussion take-aways, designated students summarizing the key points made and questions raised, or asking students to reflect and share what they learned. Rather than summarizing the discussion yourself, partner with your students; see the section on Student Roles above for strategies.

- Closing Reflection: Ask students to reflect on and process their learning by identifying key takeaways. Carve out 2-5 minutes at the end of class for students to reflect on the discussion, either in writing or orally. You might consider collecting written reflections from students at the end of class, or after class through a Google Form or CourseWorks post. Consider asking students to not only reflect on what they learned from the discussion, but to also summarize key ideas or insights and/or pose new questions.

Collect Feedback, Reflect, Iterate

How will you determine the effectiveness of class discussion? How can you invite students into creating the learning space?

Feedback: Student feedback is a great way to gauge the effectiveness and success of class discussion. It’s important to include opportunities for feedback regularly and frequently throughout the semester; for feedback collection prompts and strategies, see the CTL’s resource on Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback . You might collect this through PollEverywhere, a Google Form, or CourseWorks Survey. Classes of all sizes and modalities can benefit from collecting this type of feedback from students.

Reflect: Before you engage with your students’ feedback, it’s important to take time and reflect for yourself: How do you think the discussion went? Did your students achieve the learning goals that you had hoped? If not, what might you do differently? You can then couple your own reflection with your students’ feedback to determine what is working well, as well as what might need to change for discussions to be more effective.

Iterate: Not all class discussions will go according to plan, but feedback and reflection can help you identify those key areas for improvement. Share aggregate feedback data with your students, as well as what you hope will go differently in future discussions.

Asynchronous discussion spaces are an effective way for students to prepare for in-class discussion, as well as expand upon what they have already discussed in class. Asynchronous discussion boards also offer a great space for students to reflect upon the discussion, and provide informal feedback.

Columbia Tools to Support Asynchronous Discussion

There are a number of Columbia tools that can support asynchronous discussion spaces. Some options that instructors might consider include:

- CourseWorks Discussion boards : CourseWorks discussion boards offer instructors a number of customizable options including: threaded or focused discussions , post “like” functionality , graded discussion posts , group discussions , and more. For further support with your CourseWorks discussion board, see the CTL’s CourseWorks Support Page or contact the CTL at [email protected] to set up a consultation.

- Ed Discussion (via CourseWorks): Starting in Fall 2021, instructors will have access to Ed Discussion within their CourseWorks site. For support on getting started with Ed Discussion, see their Quick Start Guide , or contact the CTL at [email protected] . For strategies and examples on how to enhance your course’s asynchronous discussion opportunities using Ed Discussion’s advanced features, refer to Enhance your Course Discussion Boards for Learning: Three Strategies Using Ed Discussion .

References and Further Reading

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.